History has always been an open target and people often have an interest in fleshing out the past or figures from the past with contemporary concepts or even imaginary ‘facts’. For national socialists, Rembrandt was a favourite on whom to project their ideas. During the war he was venerated as the epitome of an Aryan, with strong nationalistic characteristics, before being cast as a full-blooded thorough-bred German. To a certain extent these manoeuvres with Rembrandt were supported by the historiography – including that concerning seventeenth century Dutch art. The implicit or explicit question was always, what is ‘native’ about this art and what is ‘alien’? Today, Rembrandt is once again part of the debate about Dutch identity.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-portrait with Raised Sabre, 1634

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-portrait with Raised Sabre, 1634© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

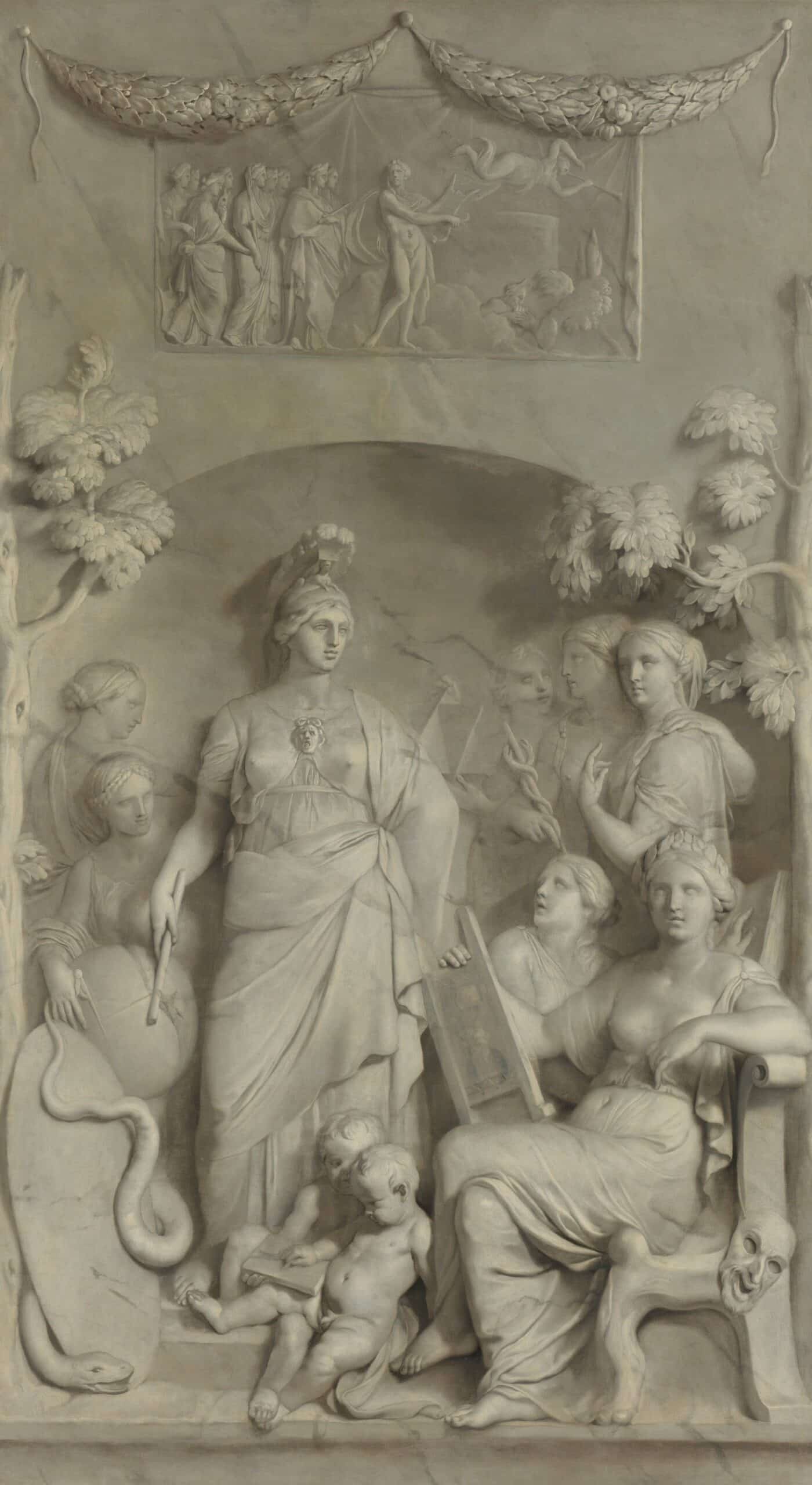

Where Rembrandt and seventeenth-century Dutch art in general are concerned, a not insignificant part of the history written since the early nineteenth century is characterised by nationalistic elements. These are especially clear where the authors detect links between a certain style and theme in painting and the intangible phenomenon referred to as the “Dutch national character”. People felt they knew exactly what was typical of Dutch art and what should be considered alien. Dutch artists who had added lustre to their work with a French or Italian accent, adherents of classicism or those who specialised in mythological themes and learned allegories were classed as un-Dutch and decadent. Gerard de Lairesse is a painter who has recently received a lot of appreciation again, but for a large part of the previous century he was held in contempt by prominent art historians because of his literary leanings, his alleged slickness and, as one of his critics put it, his “international decorator’s style”.

Gerard de Lairesse, Allegory of the Sciences, between 1675 and 1683

Gerard de Lairesse, Allegory of the Sciences, between 1675 and 1683© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In contrast to this so-called alien art there was what was considered to be very typical Dutch art, by artists who painted genuine Dutch subjects with a real Dutch palette, such as Pieter de Hooch, with his interiors showing the household being managed in exemplary fashion from beside the linen cupboard. In the eyes of the art historians of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century, pure Dutch artists were distinguished mainly by no-frills realism. More or less fixed descriptives were used for their products, some of them catchwords with a moral connotation, such as realistic, healthy, simple, middle-class, homely, sincere and honest.

Real Dutch artists were honest artisans who were – fortunately, it was thought – devoid of any form of eccentric embellishment and certainly learning. Intellectualism in art could not be genuinely Dutch.

Pieter de Hooch, Interior with Women beside a Linen Cupboard, 1663

Pieter de Hooch, Interior with Women beside a Linen Cupboard, 1663© Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Some commentators judged predominantly on the basis of artistic criteria, but there were others who related the artistic criteria directly to a political ideology, and that usually turned out to be a strongly nationalistic ideology, whether or not it was combined with a dose of xenophobia. These were not only reactionary writers either. A number of critics from the other side took the same line. In this respect, I would cite an unambiguous statement about Dutch landscape painters, made in 1931 by the then-influential and much read Christian socialist Just Havelaar. He wrote: “And where […] a Pynacker and a Both are honoured at the expense of the fine Van Goyen, the honest Potter, or even the sublime Vermeer, we say, no, never! […] because this, we feel, is where decadence comes in.”

Adam Pynacker, Italian Landscape, circa 1660, whereabouts unknown

Adam Pynacker, Italian Landscape, circa 1660, whereabouts unknownThe contested Adam Pynacker was an Italianate landscape painter, a Dutch artist who practised a style considered to be un-Dutch, a style that sickened Havelaar and his sympathisers, whereas they considered that an artist like Jan van Goyen was a glorious champion of Dutch identity.

Jan van Goyen, View on Dordrecht, 1651

Jan van Goyen, View on Dordrecht, 1651© Dordrechts Museum, Dordrecht

Hostile force

Besides the work of the abovementioned De Lairesse, that of Adriaen van der Werff, a talented late seventeenth-century classical painter, was considered even worse than Pynacker’s, if that was possible. “From Van Scorel to Van der Werff”, pronounced Just Havelaar, “Italy was the hostile force in our art”. This crassly formulated opinion was prompted by tendentious ideas about so-called national psychological differences between North and South.

Adriaen van der Werff, Shepherd and Shepherdess / Gerrit Adriaensz Berckheyde, City Hall on the Dam, 1672

Adriaen van der Werff, Shepherd and Shepherdess / Gerrit Adriaensz Berckheyde, City Hall on the Dam, 1672© Wallace Collection, London / @ Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Remarkably enough, even the usually so balanced Huizinga was tempted to make a rather presumptuous statement in terms of native and alien. In his popular book Dutch Civilisation in the Seventeenth Century, where he discusses the appreciation of Jacob van Campens’s city hall on the Dam, the great historian speaks uninhibitedly of “the disease that would deprive our civilisation in more than one way of a truly national character, French classicism”.

But there were more radical ways of putting it too, as we can see in various art reviews that were openly inspired by national socialist or fascist principles and were published in, for example, De Waag, a magazine that was fully committed to the SS ideology, and in De Schouw, the mouthpiece of the Kultuurkamer (an institute set up by the German occupiers in the Second World War, which all Dutch cultural practitioners had to join).

When seventeenth-century Dutch art was discussed in such magazines, the clichés that were already to some extent current in the nineteenth century invariably appeared. But the national socialists’ assertions and choice of words were more specific and certainly more malicious and absurd. Glorification of das Völkische (a heavily politicised term) and the adulation of their own blood and soil were a matter of course with them. This ideology seeped through into art criticism, in the description of a painting by Johannes Vermeer, for example.

Vermeer was declared pure to the bone by the national socialists, but they struggled to some extent with one of his early works, Diana and her nymphs, because it shows some unmistakably foreign, that is Italian, characteristics. In 1943, the critic Edzard Modderman (who was also the editor of the SS weekly Storm) solved the problem in De Waag with this description, “Mythological representation that is alien to the nation but dealt with by the artist in a manner that is completely homegrown, producing a painting that is totally in line with the Germanic spirit.” And, “It is a homegrown painting through and through, despite the foreign origin of the title and subject.” But, adds Modderman, “it is fair to say that those painters who specialise in foreign subjects, and especially foreign figures, must be viewed critically.”

Johannes Vermeer, Diana and her Nymphs, 1653-1654

Johannes Vermeer, Diana and her Nymphs, 1653-1654© Mauritshuis, The Hague

It got more ridiculous. In his well-known book Handboek tot de geschiedenis van de Nederlandsche bouwkunst (1941), architectural historian Frans Vermeulen lamented the decline of the Republic after the Peace of Münster (1648). He attributed this decline to French influence and added what was in his view an even more malevolent factor, “the certainly no less worrying Jewish influence […] which has been increasingly making itself felt since the middle of the [seventeenth] century and to which, in this complex set of causes, we should be even more alert than to the French influence.”

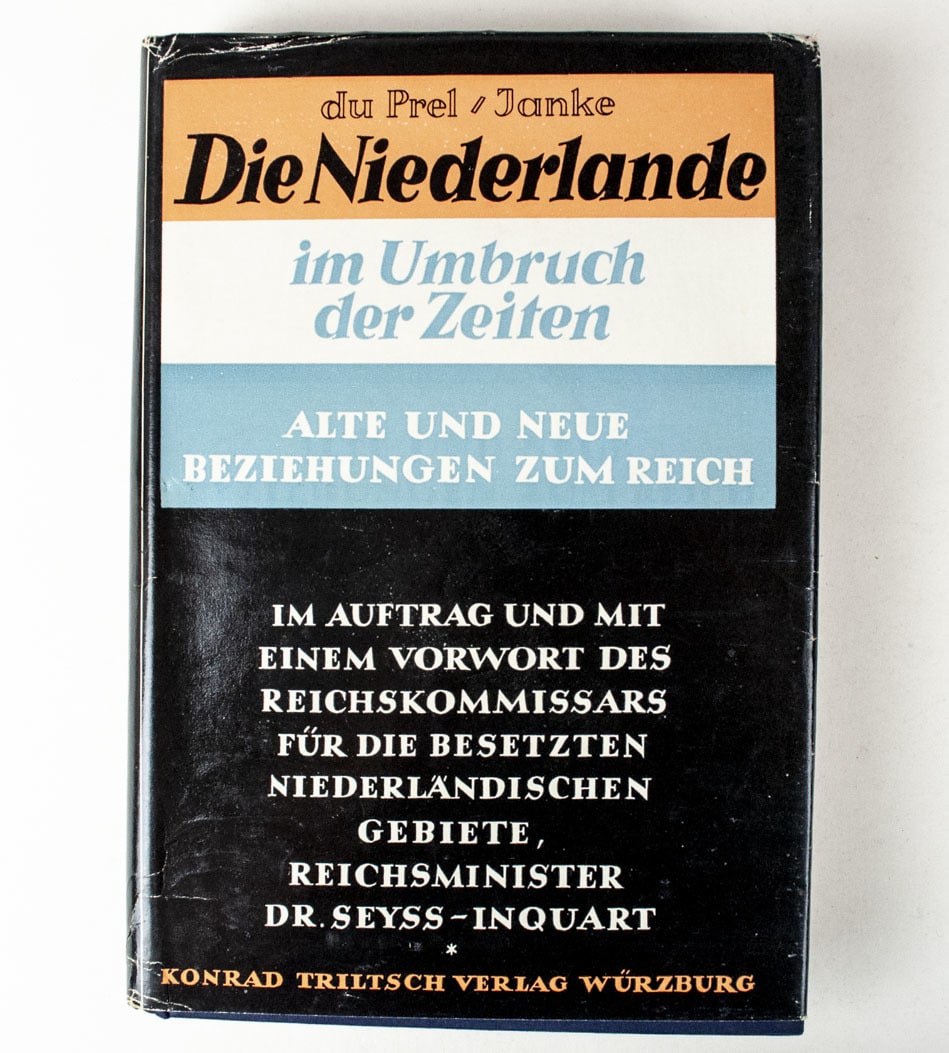

More benign than what came from Nazi writers, but equally nonsensical, was the opinion of Dirk Hannema, then Director of the Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam and, as the official wording puts it, “authorised by Mussert as the representative for museums”. In 1941 he wrote an article for Die Niederlande im Umbruch der Zeiten. Alte und neue Beziehungen zum Reich, an anthology put together at the behest of Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the government commissioner in the occupied Netherlands. In it he contended that “in its times of greatness, Dutch art has always been healthy, popular and firmly grounded in the Netherlands. It has only rarely and very superficially allowed itself to be influenced; it has either adapted foreign influences to fit its own nature or it has immediately rejected them.”

No watershed

Die Niederlande im Umbruch der Zeiten. Alte und neue Beziehungen zum Reich.

Die Niederlande im Umbruch der Zeiten. Alte und neue Beziehungen zum Reich.It is rather painful to see that there was no intellectual or aesthetic watershed between the art reviews produced by writers who had nothing to do with national socialism and those by writers who were more or less Nazi sympathisers. The standard idiom of national socialist criticism is just an extension even of, for example, Havelaar’s remarks about Italy as “the hostile force in our art”, or of Huizinga’s disdain for French classicism as a “disease that had infected our national civilisation”, despite the fact that their view of the world was far removed from that of national socialism.

Moreover, because of the use of the word disease, a statement such as the latter elaborated on a view that had been passed on repeatedly since the second half of the nineteenth century, a view that could be characterised as “a desire for purity”. It disqualified unwelcome individuals or groups, and sometimes artworks and stylistic periods with the help of (pseudo) medical imagery. Some antisemitic writers, for instance, borrowed metaphors of contamination and degeneration from the bacteriologist Louis Pasteur. According to them, people were in danger of being infected by a virus or malignant bacteria on account of Jews and cosmopolitans. Vigilance was called for as well then, but it could easily be left to das gesundes Volksempfinden. Remember, too, the description of “sick” or “entartete” art or the most recent variant in the metaphorical tradition of pathology, “homeopathic dilution”, the demise of one’s own people and culture, the nightmare of Thierry Baudet (the leader of the right-wing Dutch political party Forum for Democracy).

Decadence, disease, contamination. These were the terms that, in the first half of the last century, were generally applied in art reviews – and elsewhere – to everything that was considered to be “alien”. And the far right was definitely not alone in doing this. The distinction between native and alien proliferated in some branches of science, too, including in social geography, folklore, ethnology and – not least – in “racial science”, a heresy that managed for a long while to pass as science. Many people embraced vague concepts such as race, national character and national spirit, without a trace of scepticism, as deeply interpretable. What is also interesting is that the arsenal of terms with which national character was described is largely interchangeable with the established catchwords that earlier generations of art historians used to characterise seventeenth-century Dutch art: honest, realistic, middle-class, healthy, simple, homely, sincere.

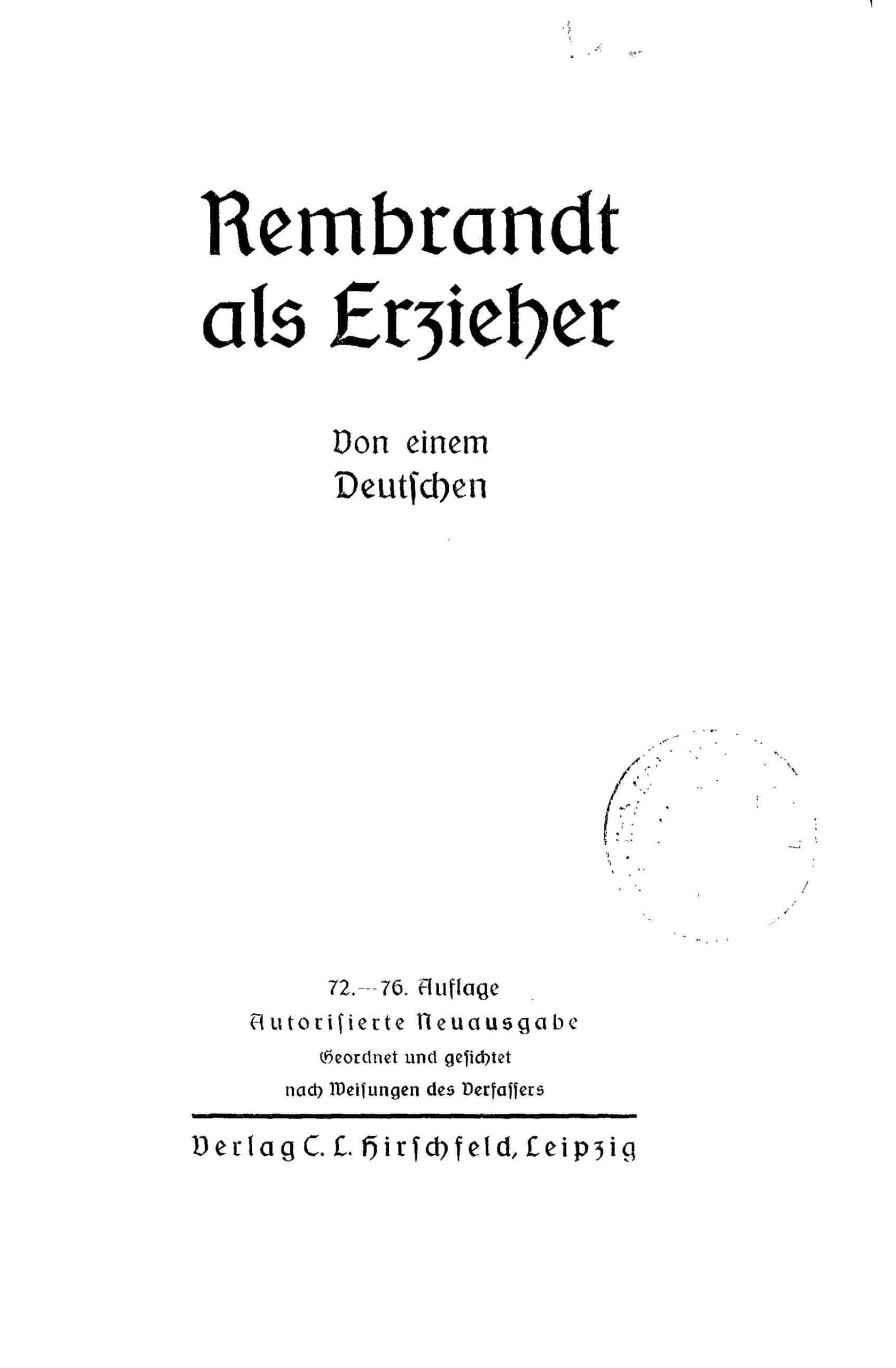

Rembrandt as educator

National socialists reserved extra terms of heroism for Rembrandt. After all, he too was an open target and he was already mythologised during his lifetime. An important moment in the proto-Nazi modelling of the artist was the publication of Julius Langbehn’s book Rembrandt als Erzieher, in 1890 (trans: Rembrandt as Educator, 2018). Langbehn was a reactionary scatterbrain, a Nietzsche epigone who fiercely opposed science and democracy and resisted everything that was considered in his day to be modern. He advocated a revival of old Germanic virtues and a new moral order, and to achieve this ideal he considered art and especially that of Rembrandt, “der deutscheste aller deutschen Künstler”, a highly effective catalyst. His book is not incorrectly referred to as a “rhapsody of irrationality”; it is certainly not a study of the historical Rembrandt. Barely dealing with him as a painter, it distorts Rembrandt into a prophet of a restored Deutschtum.

Despite the enormous amount of nonsense that Rembrandt als Erzieher contains, the book turned out to be a resounding success. Dozens of editions were published before the end of the Third Reich, and it even found a certain resonance with renowned Rembrandt specialists. The fact that it got a good press with the Nazis will be no surprise for anyone who has a look at the book. That the author dared to refer to Rembrandt as “the most German of all German artists”, might perhaps cause surprise today. But the historical imperialism professed by Langbehn did not come out of nowhere. The idea that an eminence like Rembrandt was a German or Germanic eminence had taken root among other authors too, including the historian Karl Lamprecht. It followed, of course, from the conviction that Dutch art and culture were closely related to German art and culture and should even be considered to be an inalienable part of it. Lamprecht had a very broad view of this. In his opinion, not only Rembrandt, but Oldenbarnevelt, De Ruyter, Tromp and Vondel were true Germans too.

Rembrandt was considered a prime example of the incarnation of the German soul, which was reputed to correspond perfectly to the Dutch soul.

There were some in the nineteenth and twentieth century who counted the Netherlands as “Deutsches Reichsgebiet” and considered Rembrandt a prime example of the incarnation of the German soul, which was reputed to correspond perfectly to the Dutch soul. The authoritative Wilhelm Bode, director general of the Berlin museums, did not shy away from this radical annexation either. In his monograph of the artist, published in 1906, he proclaimed Rembrandt’s oeuvre to be “rein germanisch”.

Rembrandt as Erzieher

Rembrandt as ErzieherThis would be emphasised most persistently, including in the 1940s, in journals such as De Schouw and De Waag, in which Rembrandt was endowed with epithets like “Übermensch”, “den faustischen Noord-Mensch” and “den ultra-Germaanschen mensch”, based on the old premise that there was a close causal relationship between art, a people (i.e. nation, tribe, race or blood) and country, soil or climate.

There is a very typical contribution of the blood and soil genre in a 1942 edition of De Schouw. The author is Tobie Goedewaagen, who was for a time the chief editor of the magazine, a member of the Dutch national socialist movement and secretary general of the department for propaganda and arts that was set up by the German occupiers. He characterised Rembrandt first as “a child of Dutch national character, simple and unadorned […] and so attached to the soil of his fatherland that he refrained from going on the customary trip to Italy, which all artists went on in those days”. Undoubtedly Goedewaagen had read Langbehn carefully. This is also evident in his characterisation of Rembrandt’s view of the world, which he refers to as completely “Germanic in body and soul”. In Goedewaagen’s opinion, too, Rembrandt was a pre-eminent “German”, “one of the greatest and noblest creations of the Germanic spirit”. That Germanic character was one of the most common platitudes used by those who collaborated with the Germans.

Blond Jesus

Sometimes even Jesus was Germanised. In 1929, Hitler-admirer Maria Grunewald published a study of Rembrandt’s etchings, titled Der nordische Rembrandt, or the Aryan Rembrandt. In an attempt to analyse the famous Ecce Homo etching, she was particularly struck by Jesus’s pronounced Germanic appearance. She sees him standing there, beautiful and blonde, while das reine arische Licht, which could never be extinguished, shines from his forehead and body. Jesus, she argues, appears here as a noble German, shackled, mobbed and mocked by a hostile race that seeks his demise. After which she wonders whether Rembrandt had felt like that himself when he was composing the picture. Was he not also, like Jesus, surrounded by a hostile race, in his case the Jews of Amsterdam?

Rembrandt van Rijn, Ecce Homo, 1655

Rembrandt van Rijn, Ecce Homo, 1655© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

This suggestive interpretation by Grunewald brings us to the impenetrable chapter of Rembrandt and the Jews. What writers of various signature have said about the relations – or non-relations – between Rembrandt and the Jews is based mainly on myth and speculation. There is no record of them. But those who were steadfast in the Nazi doctrine held it against the artist, who lived in the middle of the Jewish quarter in Amsterdam, that he did not hesitate to associate with Jews and to paint them. In contrast, some authors considered it opportune to completely ignore this racist aspect, so that they could embrace Rembrandt as unconditionally Germanic, free from Jewish contamination, as it were.

'A real Aryan’

There was special interest in certain works. Hitler greatly admired The Man with the Golden Helmet, a famous painting in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin (now called the Bode Museum), which was then erroneously considered to be an original Rembrandt. “This is something unique”, Hitler is supposed to have said, according to a witness, “look at that heroism, that military expression on the face. It proves that, despite the many paintings that Rembrandt made in the Jewish quarter in Amsterdam, in his heart he was a real Aryan and Germanic.”

Anonymous, Man with Golden Helmet, circa 1650

Anonymous, Man with Golden Helmet, circa 1650© Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

National socialist cultural policy attached particular value to The Night Watch, because of its martial iconography. The work was presented in De Schouw as the “heroic myth” of Rembrandt’s time and “the symbol of an ideal order”, partly due to the commanding gesture of the leader, Frans Banning Cocq. Moreover, the author of the article contemporized the picture with this wording, “Now, the law that the ‘Night Watch’ lays down really is the law by which the newly reborn and awakened nations wish to live”.

Frans Banning Cocq, detail from The Night Watch by Rembrandt van Rijn

Frans Banning Cocq, detail from The Night Watch by Rembrandt van Rijn© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

It is understandable that the Conspiracy of Julius Civilis – previously called Claudius – was popular. The poet and fervent national socialist Henri Bruning considered “Rembrandt’s Claudius Civilis […] to be one of the most beautiful and powerful expressions of our Germanism and, therefore, our race”. The painting, from 1662 (only a fragment has survived) fitted in well with the revaluation of Germanic ancestry, for which some Germanists, in particular, had worked hard. Julius Civilis counted as the leader of the Germanic tribe of the Batavians, who had fought against the Romans in 69 and 70 AD. “For us”, says a monograph on this mythical figure by the Germanist P. Felix, which was published in 1942 by the national socialist publishing house Hamer, “Civilis continues to be our national hero, the first […] to enrich Germania’s history with an important chapter!”

Rembrandt’s portrait of the warrior, sword in hand, swearing the oath with his aides, was also applauded by Frans Vermeulen, the man who lamented the French and Jewish influence on seventeenth-century Dutch culture. A page-long article, written by him in the customary bombastic jargon, was published in July 1944 in the Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden, under the suggestive headline ‘Rembrandt as a Political Painter’. According to Vermeulen, this monumental painting was nothing less than a political declaration by the painter, “zum Bekenntnis zum alt- und ewig-germanischen Führertum in verschworener kämpferischer Treu und Kameradschaft” (“a commitment to the old and eternal Germanic leadership in sworn militant loyalty and comradeship”).

Rembrandt van Rijn, Conspiracy of Julius Civilis, 1662

Rembrandt van Rijn, Conspiracy of Julius Civilis, 1662© Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Education

After 1945 The Night Watch was no longer associated with doctrinal Nazism and German Führertum. For a long time, interest in the work has been of an overwhelmingly art historical nature and more or less apolitical. Recently, however, The Night Watch has again be put to use for educational purposes in the Netherlands, as a result of politicians worried about Dutch identity. It is now compulsory for all pupils to visit Rembrandt’s painting of archers as part of the school curriculum. It is an implicit glorification of our own Dutch identity and culture and encourages children and young people to be proud of them. Clearly Rembrandt as an educator is available in different flavours.

This seems to be a new blunder, obviously of a less harmful nature than the harnessing of Rembrandt by the Nazis. But still. Apart from the fact that pride has gradually become an inflammatory sentiment, it is also absurd to have to be proud of an artwork in whose creation none of the Dutch people alive today had any part, and purely because they live on the same soil on which Rembrandt lived.

As the 350th anniversary of the artist’s death, 2019 is a Rembrandt year. You will find an overview of the most important exhibitions in this article.

Bibliography

- Kees Bruin, De echte Rembrandt. Verering van een genie in de twintigste eeuw, Amsterdam, 1995

- Martijn Eickhoff et al. (red.), Volkseigen. Ras, cultuur en wetenschap in Nederland 1900-1950, Zutphen, 2000

- Rob van Ginkel, Op zoek naar eigenheid. Denkbeelden en discussies over cultuur en identiteit in Nederland, Den Haag, 1999

- Gerard Groeneveld, Zwaard van de geest. Het bruine boek in Nederland 1921-1945, Nijmegen, 2001

- Eddy de Jongh, ‘Real Dutch art and not-so-real Dutch art: some nationalistic views of seventeenth-century Netherlandish painting’, Simiolus 20 (1990-91), pp. 197-206

- Eddy de Jongh, ‘Nationalistische visies op zeventiende-eeuwse Hollandse kunst’, in: S.C. Dik en G.W. Muller (red.), Het hemd is nader dan de rok. Zes voordrachten over het eigene van de Nederlandse cultuur, Publicaties van de Commissie Geesteswetenschappen KNAW, nr 1, Assen-Maastricht, 1992, pp. 61-82

- Eddy de Jongh, ‘De Nederlandse zeventiende-eeuwse schilderkunst door politieke brillen bezien’, in: Frans Grijzenhout en Henk van Veen (red.), De gouden eeuw in perspectief. Het beeld van de Nederlandse zeventiende-eeuwse schilderkunst in later tijd, Nijmegen, 1992, pp. 225-249

- Els Kloek en Leen Dorsman (red.), Nationale identiteit en historisch besef in Nederland, Utrechtse historische cahiers 14 (1993), nr. 4

- Rob van der Laarse et al. (red.), De hang naar zuiverheid. De cultuur van het moderne Europa, Amsterdam, 1998

- Ivo Schöffer, Het nationaal-socialistische beeld van de geschiedenis der Nederlanden, Arnhem-Amsterdam, 1956

- Fritz Stern, The Politics of Cultural Despair. A Study in the Rise of the Germanic Ideology, Berkeley etc., 1974

- Claartje Wesselink, Kunstenaars van de Kultuurkamer. Geschiedenis en herinnering, Amsterdam, 2014