Marie Reintjes Wants to Be Able to Paint Everything

Marie Reintjes (b. 1990) is always looking. As soon as she sees something that intrigues her, she wonders how she can transpose it into paint. Her eye often falls on everyday, seemingly trivial subjects: a radiator, two boots, a pair of pants with dots. Her painting style is as dynamic as these images are still.

Marie Reintjes

Marie ReintjesThere’s a well-known optical illusion in which you see the face either of young girl or of an old woman. In a certain sense Marie Reintjes’ paintings are reminiscent of this. One moment you notice the depicted scene, the next the paint itself seems to take centre stage. Within one and the same painting figuration and abstraction take it in turns to demand attention. For Reintjes it’s not the subject that’s intrinsically interesting: for her it’s more about the shapes and colours. If something catches her eye, she immediately wonders how she could paint it.

That greedy attitude results in a steadily growing oeuvre consisting of paintings, subjects and styles that sometimes differ widely from one another. Her career is growing too: she has now taken part in a variety of duo and group exhibitions in the Netherlands and abroad. In 2017 she was also granted a Young Talent bursary by the Mondriaan Fund.

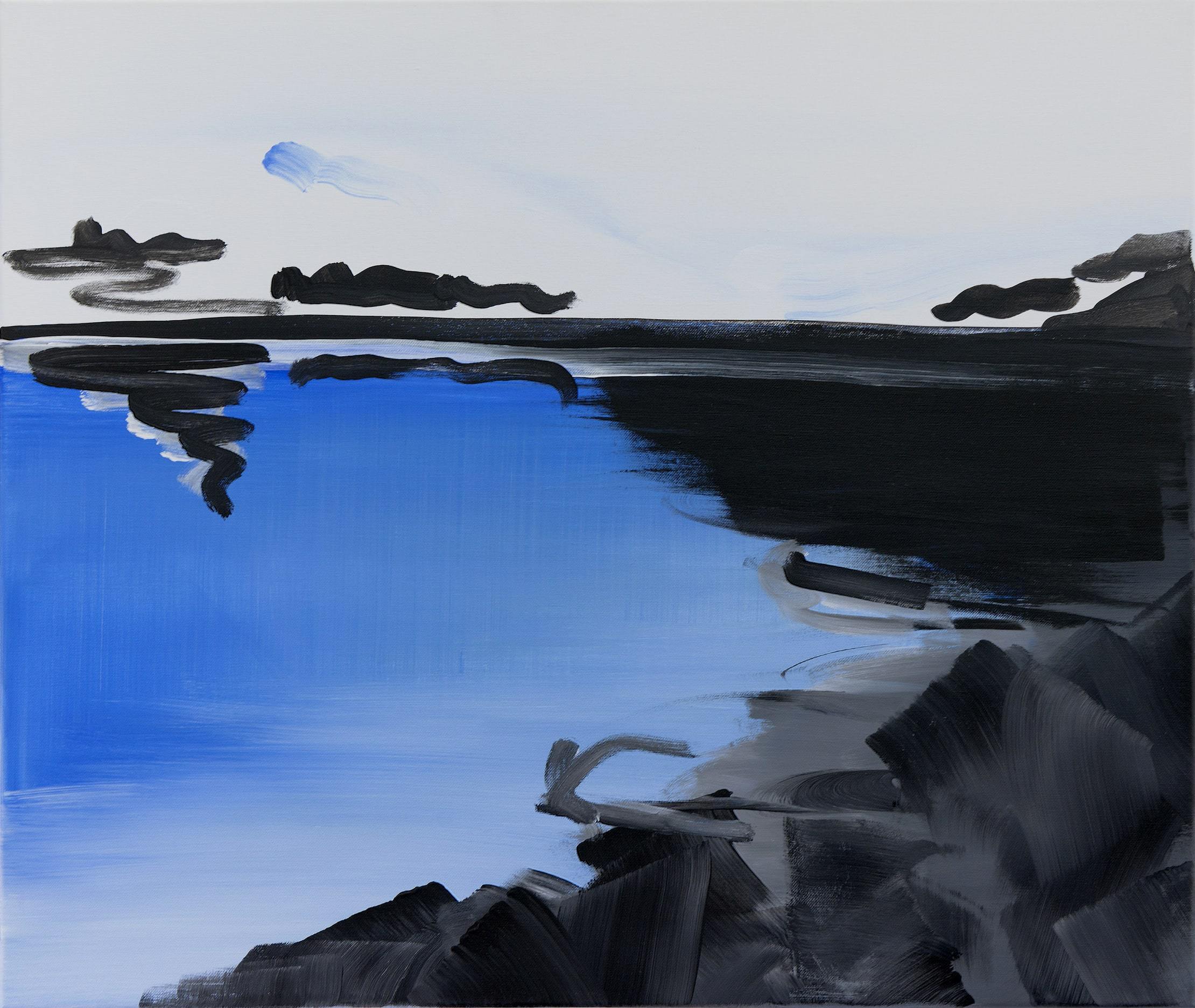

Norwegian Landscape (2018)

Norwegian Landscape (2018)© photo Marjon Gemmeke

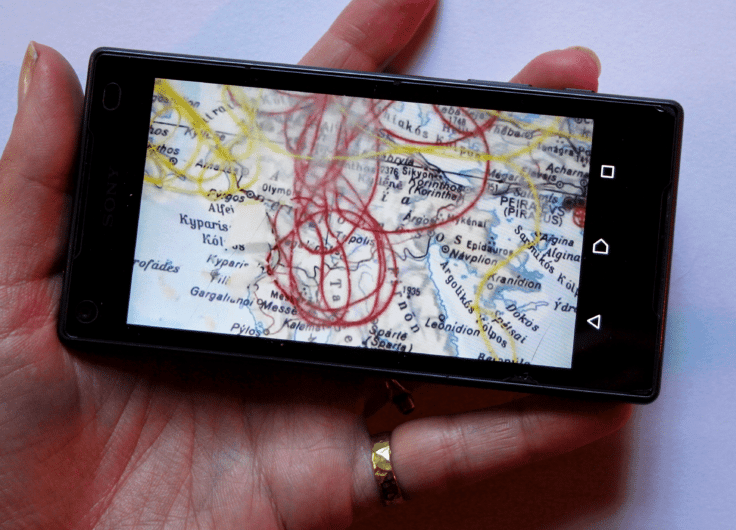

Ground level

Reintjes works on the basis of photos. On her phone the files are full to bursting. She often picks out everyday subjects: people talking in a café or on a train, a ceiling light, a rather melancholy dog. She certainly doesn’t shy away from bigger topics, but at the same time nothing is too small or too simple for her: she has painted a sweeping Norwegian landscape, but also a vase of flowers on a table. After all, both caught her attention. She’s always on the lookout, as this kind of art demands an attentive gaze.

Freesia IV (2017)

Freesia IV (2017)Reintjes is aware, however, that even her practised vision has blind spots: she once walked through the city with someone who remarked on everything to do with the building façades. That made her realise that her gaze was much more focused on ground level, which in fact fits in well with her interest in the simple and even banal.

Art history certainly plays an important role in Reintjes’ work. She uses well-known painting motifs and feels a kinship with the romantics’ experience of nature. Her work, however, seems more open and inviting than theoretical or cerebral. One of the first things she learnt was suggestion: allowing the viewer to complete the painting in their head.

Her canvases can have a threatening feel or invite you to wonder what happened outside the picture, as in the unmanned, floating Canoe (2016). A potential narrative interpretation does interest her, but it wasn’t the point of departure when she picked out the photo on which she based the painting. What initially attracted her was something more formal, almost more abstract: the contrast of the yellow canoe on the blue water.

Canoe (2016)

Canoe (2016)Reintjes’ work seems to revolve around the pleasure of how things look and how they can then be painted. While the subjects often seem quiet, the paint is applied in a dynamic and lively fashion – exuberant might be the best word. You can see the movements clearly; they’re not obfuscated or smoothed out. It’s certainly not wild action painting; more of an insightful mode of depiction. The viewer often gets a good idea of how the canvases came into being and how many brush strokes or what kinds of movements would have been necessary. Together with the choice of subject that gives Reintjes’ paintings an intimate flavour.

Intuition

The photos really serve as a starting point. Sometimes Reintjes adds something or displaces an element of the image, but nine times out of ten she leaves things out. However it’s always the painting itself that quickly gains priority, with the end result arising by feel. After much practice the trained gaze has become intuitive; comparable with improvisation by a trained musician.

Reintjes gets a real adrenaline kick when painting, because if you paint so succinctly then a wrong move or decision can have big consequences. Everyone has a limited capacity for imagination, she says, but by taking action you can get over that limitation. In fact when she has a very clear idea of what she wants to do, it gets in her way. She picks up a painting of a wild boar’s carcass and points out the bits where by her own admission she was thinking too hard.

Train Journey to the Beach, 2017

Train Journey to the Beach, 2017The boar’s carcass ended up in what Reintjes calls the naughty corner: a row of paintings with their fronts to the wall, as their maker doesn’t want to look at them (for now). She makes her paintings quickly, in part because a small surface is simply painted faster, in part because that enables her to paint intuitively. It often only takes her half an hour before she knows whether a painting is a success or not.

As she has gained more space, she has also felt the need to work on larger canvases, although her works of art are never very large, let alone prominently monumental. The same modesty is visible in the proportions of the canvases as in the style whereby a couple of brush strokes are enough to establish representation. This is beautifully concise art.

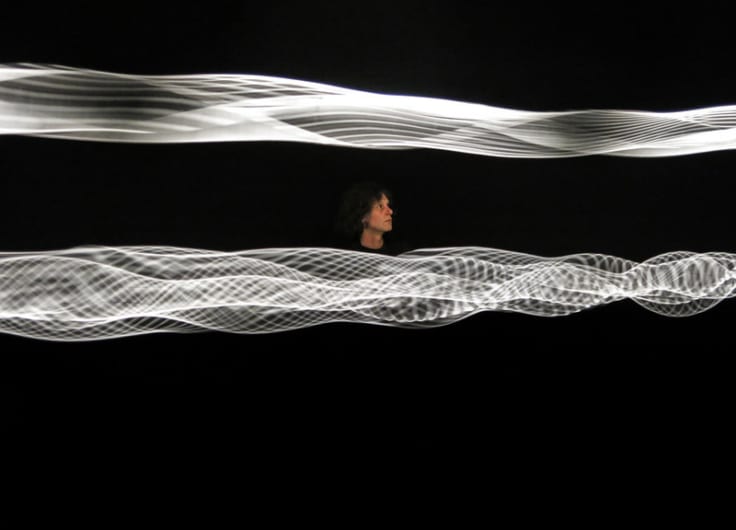

Dreaming in the Saltwater, 2019

Dreaming in the Saltwater, 2019Elusive

A number of recent, larger canvases are reminiscent of calligraphy. In Dreaming in the saltwater (2019) a couple of lines form an entire landscape: one squiggle denotes a mountain, another a stream. Vegetation is represented by a green scrawl. The elements of the landscape are barely worked out, but at the same time it’s clear what there is to see: an advanced brevity which, besides calligraphy is also reminiscent of pictograms or symbols on a map.

This calligraphic style isn’t necessarily new in her work: a somewhat comparable style is also visible in earlier work such as Wave (2016), but on a much smaller surface: 18 by 12 compared with the 80 by 85 centimetres of Dreaming in the saltwater. On such a small surface of course a brush stroke is much more prominent.

Wave, 2016

Wave, 2016The comparison between Wave and Dreaming in the saltwater really shows how difficult it is to pin down Reintjes’ style. Her hand and eye can repeatedly be found in her paintings, but the development is difficult to trace, she admits herself. Those who like to see that a painter has developed in a linear fashion, for instance moving gradually from figuration to abstraction, feel betrayed. The diversity has increased rather than decreased.

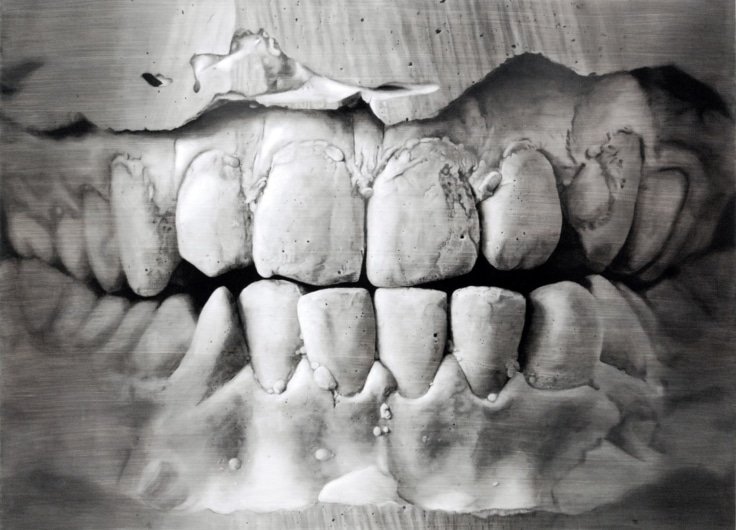

Pretty Boy and Dirty Boots, 2018

Pretty Boy and Dirty Boots, 2018In 2018, for example, she painted Dirty Boots and Pretty Boy, both very realistic for Reintjes, with the boy consisting of a limited number of thick, winding strokes. A sparse canvas like Bottle dates back to the year before, while the unprepared onlooker might well think that Reintjes had whittled down her style to a bare essence. It’s more or less impossible to place these canvases in chronological order based on style.

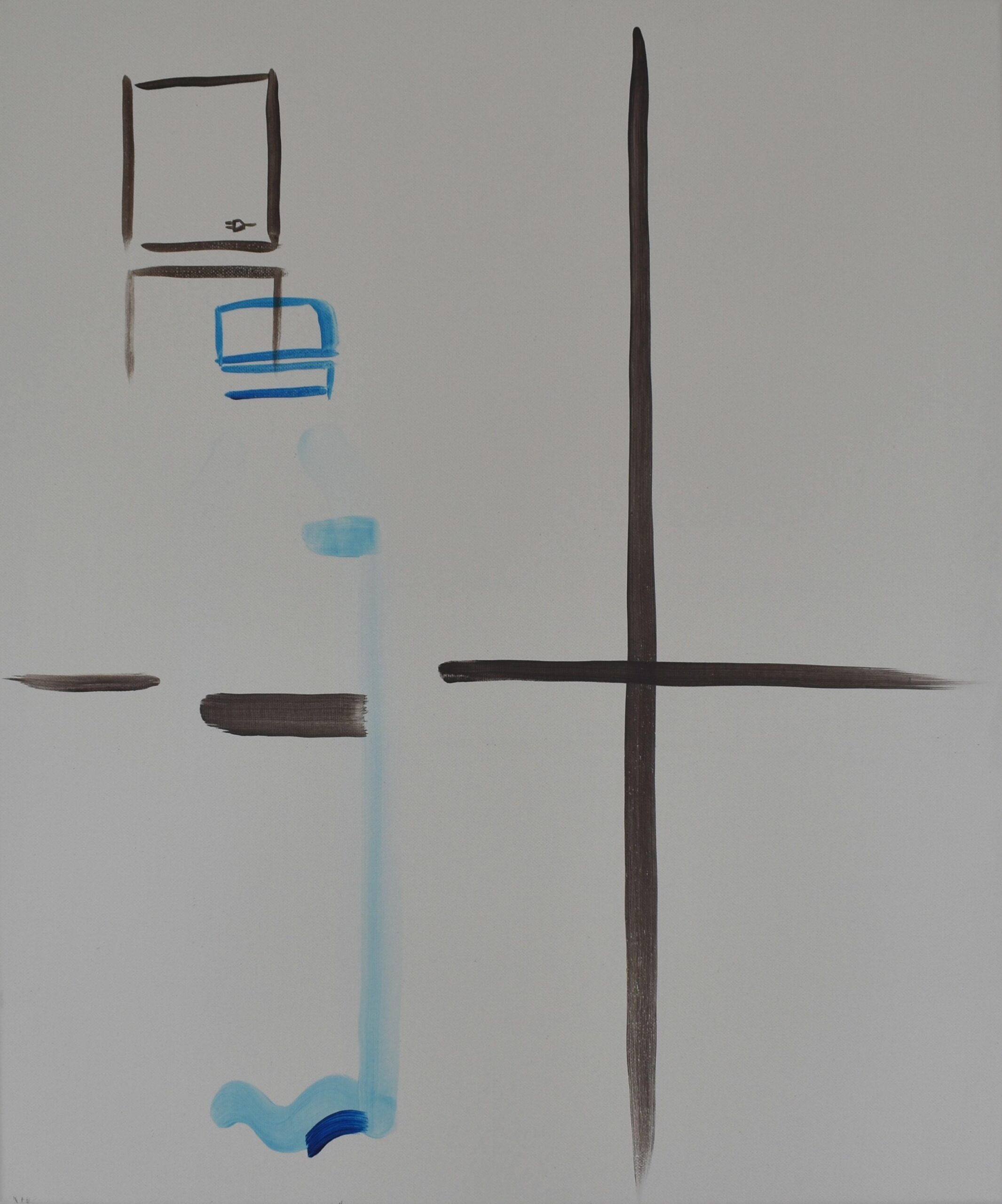

Bottle (2017)

Bottle (2017)She herself doesn’t like the idea of definitively committing to one particular style or method. She also doesn’t like painting things she already knows how to paint: by going in search of solutions she keeps herself sharp and enthusiastic. Every subject demands its own approach, which also leads to stylistic diversity. Moreover that attitude gives her art something pleasantly elusive, while always remaining inviting: try looking around you from time to time as Reintjes does. Imagine that all that could be rendered in paint.