Marit Törnqvist’s Children’s Books Are Tiny Islands With Peaceful Moorings

Now that writer and illustrator Marit Törnqvist has received the prestigious Johannes Vermeer Prize – the first artist to do so producing work exclusively for children – writer Yelena Schmitz once again immerses herself in the books she so happily grew up with. ‘Her clear language invites me to feel at home.’

On Monday 4 November, the Swedish-Dutch author Marit Törnqvist received a major prize for her writing. In this light I’ve been rereading her work from A to Z. It’s a gift and I highly recommend it: place all those books around you like tiny islands where you can moor your boat. I browse her work and relive the feeling I had as a young reader viewing her illustrations: it’s peaceful here and there’s space for me.

Marit Törnqvist received the Johannes Vermeer Prize, making her the first artist to do so producing work exclusively for children

Marit Törnqvist received the Johannes Vermeer Prize, making her the first artist to do so producing work exclusively for children © Rogier Veldman

Now that I’m a writer myself as well as a reader, I’d like to take a deeper dive into her books. And perhaps many others would like to join me. With the new recognition brought by the Johannes Vermeer Prize, some of her books are being reprinted – in some cases for the tenth (!) time. How does the universe of Marit Törnqvist look? What does she love and what is she looking for? How do her life and work intertwine?

When I think of her books, I think of islands, boats, friends, loved ones, grannies, granddads, attic playrooms, letters, carpets of snow, autumn leaves and fields of sunflowers. Törnqvist’s characters often set off on an adventure, in pairs or alone. Sometimes they wait, all alone, in an open landscape, high in a tree, up a tower or up a pole in the wild sea. There’s something pure about that solitude. A longing for love and connection, the feeling that everything has yet to begin: ready for that one encounter.

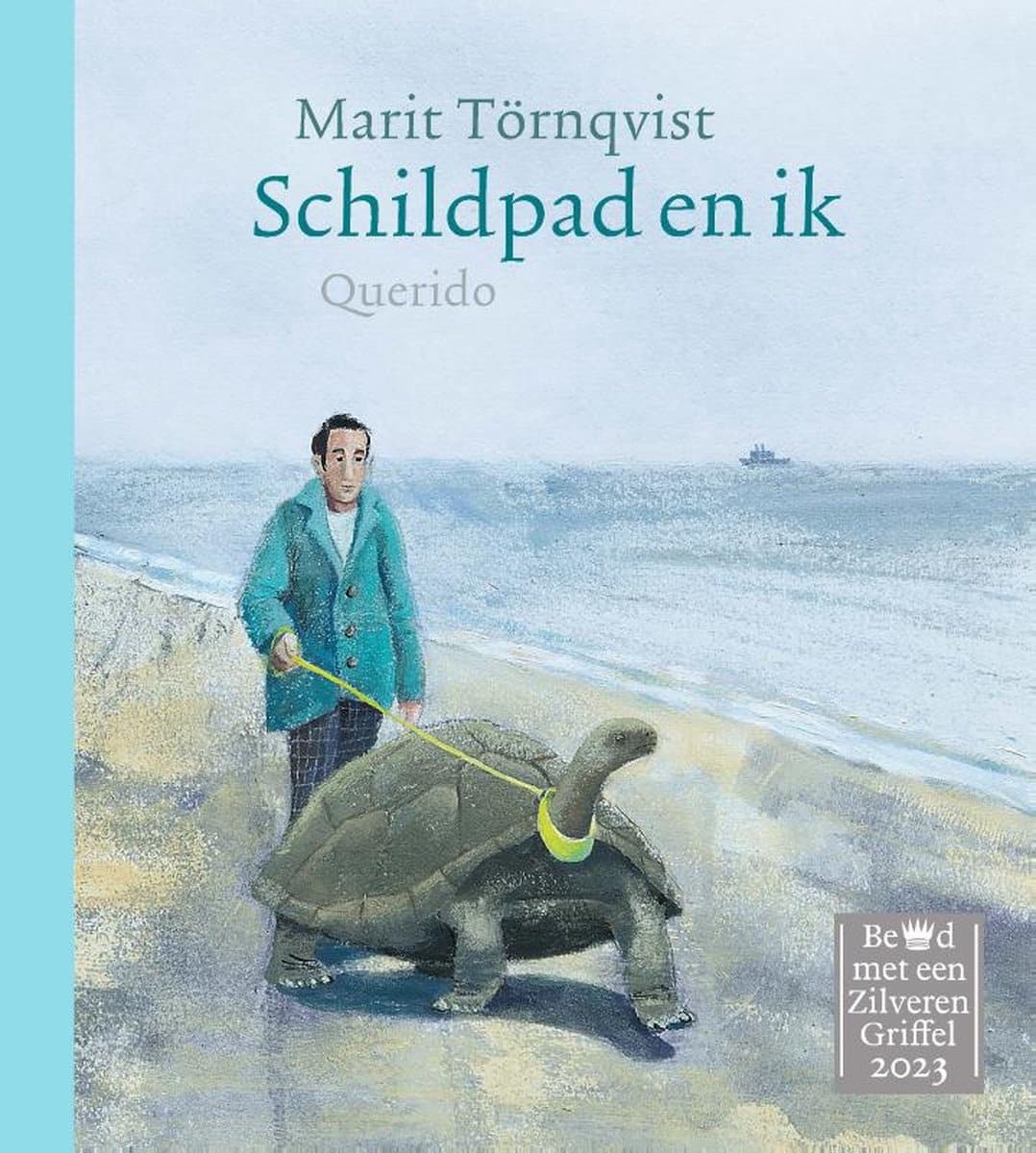

Tortoise and I

Around me lie books from the last thirty years: Törnqvist’s illustrated work with Astrid Lindgren, her Klein verhaal over liefde (‘Little love story’), for which she received her first prize, the bestseller Jij bent de liefste (You Are the Loveliest), but also Het gelukkige eiland (‘The happy island’), We bakken een dierentuin (‘We’re baking a zoo’), Een boek voor jou (‘A book for you’) and Schildpad en ik (‘Tortoise and I’). In Schildpad en ik, which was nominated for the Boon Literature Prize in 2023 and won the Zilveren Griffel, I recognise themes and layering that recur in several of her works. Soft, timeless pictures tell the story of a boy who is given a tortoise by his granddad. Let me find you a quote:

From that moment I knew for sure: Tortoise would always stay with me! All my life.

Tortoise and I

Tortoise and IFor young readers, the tortoise is a beloved and exceptional animal. You can feel the unconditional love for a first pet or teddy bear: we belong together. Older readers realise that the tortoise might represent far more than that. But what precisely? Törnqvist never imposes her own interpretation – that’s the strength of her work. The tortoise could be a metaphor for your background and the country where you feel at home. It could be about the “baggage” you carry with you. Or the parts of your life you can’t or aren’t always allowed to share. Everyone has something they’d rather hide away because it doesn’t fit in with others.

While my friends found their first loves on the dancefloor, I had a tortoise with me that everyone tripped over.

Tortoise grows and grows and no longer fits into the boy’s life. There’s a deep sadness in this book that transitions into rejection and alienation.

‘You guys belong in a zoo!’ the children in my class exclaim. They drew an enclosure on the pavement slabs of the school playground. We were imprisoned.

The boy decides that he and the tortoise can’t go on together. The tortoise has to go and someone else will take care of him. But it’s very hard to let go. On their travels the boy and the tortoise encounter each other again: their reunion brings catharsis.

Where we were, there was tortoise, and where tortoise was, there were we.

The story isn’t just the story of a boy, but also of his granddad, and so many others. It offers comfort.

After reading Schildpad en ik I can no longer watch passers-by from a distance. What tortoises are they carrying with them? My eyes are full of love, empathy and curiosity. I feel a hunger for encounters with people I don’t yet know. It strikes me as revolutionary that a short book with a handful of sentences can evoke so much.

Hiding in language

Personally I’ve long felt drawn to Törnqvist’s work, which combines tenderness with lightness, a hint of pain but always strength. Her clear language invites me to feel at home, something that as a reader from Belgium I don’t always feel in work from our northern neighbours. I suspect that has something to do with her own background: Marit Törnqvist grew up in two countries and has spent her whole life pulled between Sweden and the Netherlands. Or perhaps pulled isn’t the right word. She’s at home, she tells me on the phone, there in her fourth-floor studio in Amsterdam. “All my life I’ve been living between two countries. Now I’m back in Amsterdam, last week I was in Sweden. ‘You’re home again!’ say friends here in the Netherlands. But my Swedish neighbour says the same when I open the door in Sweden. I sometimes feel like everyone only knows half of me.”

Törnqvist during an exhibition at the museum Astrid Lindgrens Näs, Vimmerby, 2019

Törnqvist during an exhibition at the museum Astrid Lindgrens Näs, Vimmerby, 2019© Orjan Karlsson

She knows what it’s like to be at home in different places. Or perhaps not to belong anywhere? “This morning the first thing I did was look at the weather. To see if it was already freezing in Sweden. Lots of people have two countries. I understand what that is – sometimes being elsewhere in your head. It doesn’t even matter which two countries they are. I instantly feel a bond with people who have that too.”

There’s something pure about the solitude Törnqvist brings to her books. A longing for love and connection, the feeling that everything has yet to begin

Her work has been translated into thirty languages (and she always takes on the Swedish herself). “When I write, I write in Dutch. But I translate it into Swedish right away in my head. For every sentence I ask myself, will my other country get that? Perhaps that explains why my work is sometimes described as timeless and placeless.” You’ll never catch Marit Törnqvist using garish or hyped language, or regional expressions. There’s peace between her sentences in which many readers feel welcome.

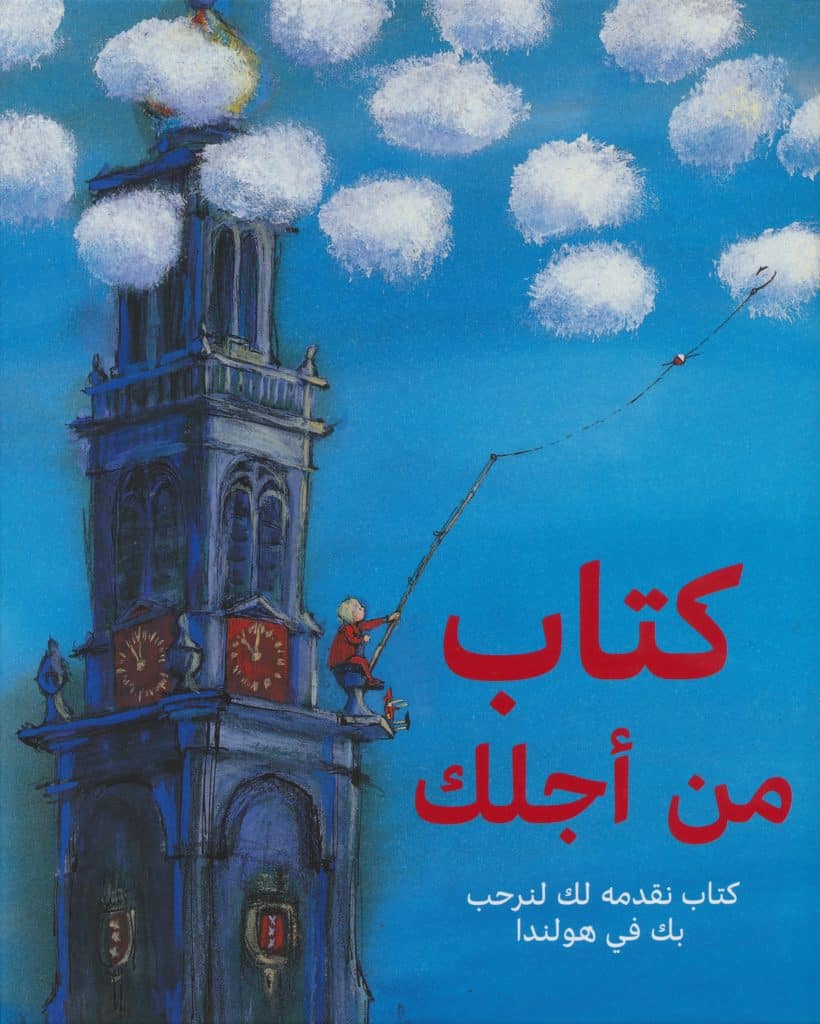

‘Een boek voor jou’ (‘A book for you’), with stories and illustrations by various authors, including Annie M.G. Schmidt, Fiep Westendorp, Toon Tellegen, was published in Arabic, Farsi and other languages

‘Een boek voor jou’ (‘A book for you’), with stories and illustrations by various authors, including Annie M.G. Schmidt, Fiep Westendorp, Toon Tellegen, was published in Arabic, Farsi and other languagesBelonging is a major theme in her work. In 2023 Törnqvist put together an anthology of stories translated into Arabic, Farsi, Turkish, Somali, Tigrinya and Kurdish, with the title Een boek voor jou (‘A book for you’), and ten thousand copies were given out to children in asylum centres. In a time (and culture) where everything is boundaried, weighed and measured, Törnqvist literally offers “a book for you”. A gesture of love, humanity and warmth where you can take shelter in language.

Personally I associate her books with my own home and the houses I stayed in as a child. I remember her illustrations in the iconic Jij bent de liefste, published in 2000 with authors Hans and Monique Hagen. Small, safe pictures that you could read at a young age. I still remember my best friend having the book in her toilet. My own copy is still on my bookshelf. The book is dedicated to her daughter Jasmijn, along with Hans and Monique Hagen’s daughter. Jasmijn must be around my age.

The authentic book

The better part of thirty years on, I see parallels between Marit Törnqvist and myself: a great love for children’s literature and an outward gaze. How do you create strong work and how do you continue to take an engaged look at the world? Törnqvist gives me tips. “I’ve always gone for the authentic book. I’ve followed my intuition. Taken a really long time over a book. Said no lots. Sometimes not written for a while. Sometimes worked for free. Earned money doing other things so that I could write and draw what I wanted. I always felt strongly that the book needed to remain authentic.”

Where and from whom did she learn all this? An important encounter in her life was her meeting with Iranian writer Zohreh Ghaeni at an international children’s book festival in 2004 in Tehran. “I’d read the graphic novel Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi and went to Iran. As soon as I arrived at the airport I could see everything moving around me. I wasn’t just on a trip, I was living in that book, I could feel everything. In the evenings at dinner with other festival guests, I mentioned that I’d been reminded of the little girl saying goodbye to her uncle who was to be executed in prison. The woman next to me listened and said: my husband was executed at the same time. And I was in that cell too. That was Zohreh.”

Marit Törnqvist in her studio in Amsterdam: ‘When I write, I write in Dutch. But I translate it into Swedish right away in my head. And for every sentence I ask myself, will my other country get that?’

Marit Törnqvist in her studio in Amsterdam: ‘When I write, I write in Dutch. But I translate it into Swedish right away in my head. And for every sentence I ask myself, will my other country get that?’© Chris van Houts

That first conversation sparked a friendship and fervent alliance that spanned decades. “Zohreh’s a fighter. She looks for the loopholes in her country. Protest is impossible for her. She’d be murdered. But she can make books and distribute them. She’s so inspiring in her force, courage and empathy.” Törnqvist and Ghaeni share that belief in the power of books. Törnqvist was involved from the beginning in Read With Me, a project that enables children otherwise lacking access to books to read and be read to.

To Marit Törnqvist making children’s books is more than just making children’s books. It’s not just painting and drawing. It can change lives. “We live in horrific times. To me, it feels as if every day there’s a fight against culture. And against children.” Marit Törnqvist points to the thorn in our conversation: the times we live in, and how to relate to them. “In that respect, I really admire Astrid Lindgren. It’s incredible the way she was friends with the whole world, and at the same time produced so much activist writing.”

Marit Törnqvist sits on a raft and floats on the waves of world literature. She waves to other rafts and doesn’t sail away from pain or violence. With her books, she builds jetties and harbours. Prizes bring attention, translations and more reprints. Along with much-needed recognition of the importance of children’s literature. I’d like everyone to have a chance to immerse themselves in her work: her illustrations are places of refuge, as if you’re floating in a quiet boat on a big lake, sipping of warm tea.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.