A Multi-Purpose Monster. ‘Mary’ by Anne Eekhout

The premise for Anne Eekhout’s fourth novel is a good one: to write Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, out of the shadows of her illustrious context. Unfortunately, her straightforward style leaves too little of Mary’s complex mind unturned.

On 12 May 1933, Virginia Woolf writes in her Italian travel diary about Casa Magni, the white villa on the blue bay of Lerici where Mary and Percy Shelley often stayed: “Shelley’s house waiting by the sea, & Shelley not coming, & Mary & Mrs Williams watching from the balcony & then Trelawney coming from Pisa, & burning the body on the shore – thats (sic) on my mind.”

Woolf’s tragic drowning tale of the romantic poet who loved to sail, but who could not swim, is a well-known story. But I was more taken by Woolf’s focus upon the waiting Mary. Anne Eekhout was similarly captivated when she visited the Keats-Shelley House in Rome. There, she conceived of the plan for her novel Mary. It would be Eekhout’s first story written with an inkling of truth in it.

Anne Eekhout

Anne Eekhout© Keke Keukelaar

Mary Shelley (1797-1851) grew up in a stimulating environment. She was the child of what were at the time radical thinkers (the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and the political philosopher William Godwin), and she was the love interest of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (who came into her life as a great admirer of Godwin’s revolutionary ideals). Intellectual fodder, however, could not make up for the lack of an emotionally warm environment or loving recognition. Mary’s mother died of childbed fever a few days after she was born and Mary Jane Godwin, the neighbour whom her father married four years later, never got on well with the child; “(…) this mother or no mother?”, Eekhout’s imagined Mary considers: “And her thoughts always settled on the same thing: no mother.”

In her novel, Anne Eekhout focuses on Mary’s struggles as a half-orphan, as a young mother, and in her love life. She highlights two brief but formative periods in her life, alternating between them. On the one hand, in first-person perspective, she delves into the Scottish adventure of 1812 in which Mary ends up with the Baxter family in the port city of Dundee, ostensibly for the treatment of a skin ailment, but more probably at the impetus of the tense relationship with her stepmother. It was an exile that Mary Shelley herself later regarded as a great stimulus for her imagination. Eekhout alternates that episode with a now canonical story; the genesis of Frankenstein during the rain-soaked summer of 1816 that the Shelleys spent on Lake Geneva in the company of Lord Byron and his young physician John Polidori. On one of those stormy evenings, while reading horror stories around the fire, the plan arose to hold a ghost story competition. Only Polidori would eventually finish and publish his story The Vampyre (1819). But Eekhout’s novel does not go that far – it ends when the Shelleys leave the Alps at the end of August, Mary’s debut still largely unwritten.

Portrait of Mary Shelley (1797-1851) by Richard Rothwell

Portrait of Mary Shelley (1797-1851) by Richard Rothwell© Wikipedia

Eekhout’s Mary is a flower in the bud, yet to prove herself. The choice to focus solely on Mary’s formative years is the right one – after all, these are her most defining years. In doing so, Eekhout suggests that Mary’s debut novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus came out of those turbulent years, threading this together with her focus on motherhood. Childbed grief is threaded through the novel as a constant motif – Mary Shelley not only lost her own mother to postpartum blood poisoning, but her own first child was also too small and weak to survive. Eekhout emphasizes psychological suffering, and as historical novels are always influenced by the contemporary views of the writer, she frames this motif in an especially popular-psychologizing way. “‘Oh, child,’ I whispered. It had lived.”

The choice to focus solely on Mary’s formative years is the right one

Unlike in Eekhout’s rather contemporary retelling, biographer Fiona Sampson allowed Mary’s strong personality to emerge from all this loss and grief (In Search of Mary Shelley, 2018): she has to make do without a mother and with a father who focused mainly on his work, so she runs away from home with a married revolutionary poet who espouses free love. From the moment she leaves her home, she is completely on her own, she has to reinvent herself. It is precisely this solitary position that forms the core of her evolving personhood.

This passionate, fearless Mary shines through all too vaguely in Eekhout’s version. Her superficial dialogues and explanatory one-liners render a reductive image of a woman who is a victim of her time, of her context, and of the men who surround her. Eekhout’s poor style also prevents the creation of a layered and intellectual character. At times the syntax is of toe-curling simplicity: “We went (…) We walked (…) We sat (…) I had (…)” She writes that Mary’s story “will be about the scariest that there is. Longing, loss, grief,” but those themes are handled with such inadequate language that the intelligent voice that echoes in Mary Shelley’s own writings is lost. As a girl, she was not destined for Eton, but her unofficial education – fueled by conversations at home, her father’s library, and the debate evenings she was allowed to attend – was unmatched. She grew up in a period of rapidly increasing complexity. With her intuitive approach to the gothic novel, Mary Shelley testified to the elastic mind necessary for a sensitive understanding of the cultural and political evolutions of the time: she writes in technology, alchemy, references to Coleridge, Milton and the classics, and interweaves these with the romantic ideal of individuality and its consequences. Very little of that complex spirit remains in Eekhout’s Mary.

Eekhout's adagio is that imagination breathes life into reality

Eekhout does tackle the suspicion of the time that Percy, not Mary, had written Frankenstein – or at least that it must have been a collaboration. She plays the feminist card, but does so, again, rather straightforwardly. The supporting characters – predominantly male – function as one-dimensional filler against which to contrast her protagonist. Percy, for example, appears as an insecure egomaniac subject to mood swings that verge on the childish. We know from Mary’s correspondence that their relationship was less than smooth, but what close relationship is? Mary might have rationally agreed with his ideal of free love, but she suffered emotionally. “She tries to reconcile the inherent logic of free love with the deep sense of injustice and sadness she feels when he takes another (Claire!) into his arms.” This love triangle with her stepsister Claire was difficult for Mary, and then there was also Hariet, Percy’s official wife, with whom she was pregnant at the same time. Yet all these difficulties did not hinder their love and deep understanding for one another: Mary and Percy discussed and edited each other’s work, they wrote in the same journal, and they were spiritual equals.

In Eekhout’s novel, Mary often finds herself gloomy and alone while Percy once again spends the night with Claire, while the passion they share is paid little attention. Even in confrontation with other men, the same line of thinking returns. Byron, for example, treats Mary with respect; “like a man” writes Eekhout. It is telling that even in her acknowledgements, Eekhout makes a distinction between lieve schrijfsters, lieve vriendinnen – dear female writers and friends – and lieve wijze mensen – dear wise people, who she lists as only men. One could wonder whether, with our supposedly progressive views, we necessarily look more openly upon those more rigid times.

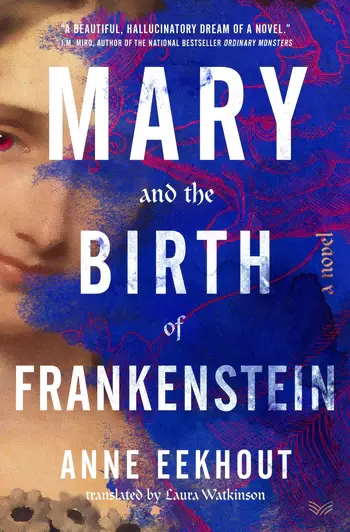

US edition of Mary

US edition of MaryEekhout’s adagio is that imagination breathes life into reality. Her motto, borrowed from Mary Shelley, is that “telling the best possible story matters more than the truth”. But instead of loosening the reins of fantasy – as Jeanette Winterson does in Frankusstein

(2019) – she falls into clichés. This notion returns time and again throughout the novel in meaningless dialogues, but the tension between fact and fiction is never further developed: “So he lost his imagination because he cared about the truth.” “I think so. Perhaps one should not want to make a clear distinction between imagination and reality.”

Perhaps not, and so Eekhout deviates from the biographical facts on several important points, and certainly as far as the Scottish period is concerned, takes a strongly romantic turn by depicting a forbidden lesbian infatuation between Mary and Isabella Baxter:

How her mouth caressed mine, my lips licked like cream. (…) We were here together, swam in this lake, knew ourselves to be unattainable, because we had created this lake together. The water was taut, blotches of light between tree leaves. And there, among the branches, he stood: our monster.

This novel demonstrates that style cannot just be the cherry on top of a great story

Many adaptations have already shown how versatile Mary Shelley’s monster is. In this case, it takes the form of “that which she does not want to know about her own body” and the threat of a paternalistic David Booth, Isabella’s future husband. Invigorated by the mysterious atmosphere around the dubious Booth, and fed by the Scottish landscape and its mythology, the fictionalization of this period is the most free, but also the most successful. It is also quite clever how Eekhout plays with different genres. She mixes coming-of-age passages with horror stories and folk legends and concocts strange scenes that soar with tension. Much less successful are the passages that she overwhelms with psychological platitudes – “Face that which you fear” – and those in which she is grasping at imagery: “When (…) a moving curtain of swallows flies over, like a sheet on the clothesline in the wind.” Or: “The bed curtains moved with an insatiable desire, one that drove me into a half-sleep.”

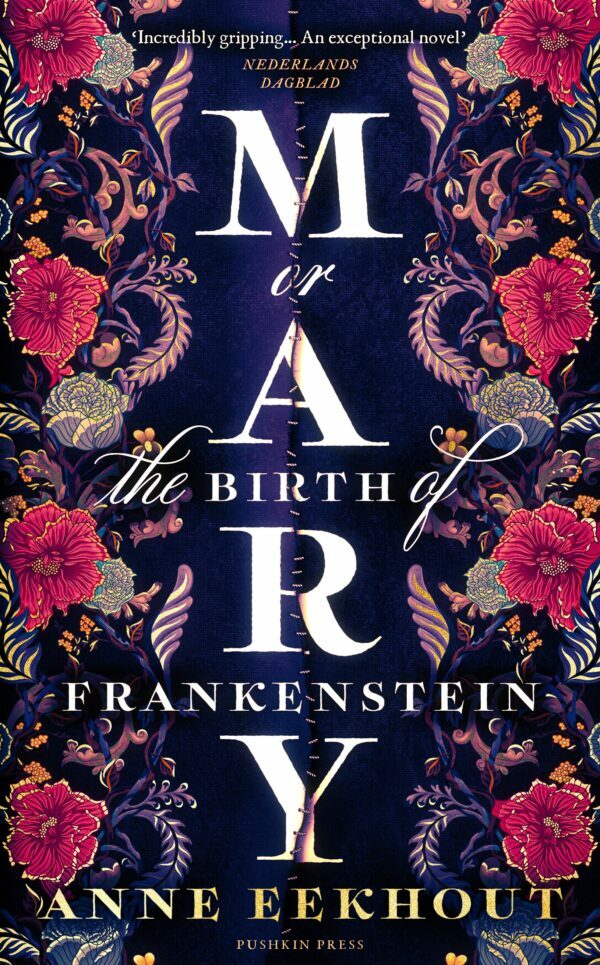

UK edition of Mary

UK edition of MaryAnne Eekhout could have flourished with Mary. The premise is a good one: to write Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley out of the shadows of her illustrious context. The narrative material is rich and fascinating, but this novel demonstrates that style cannot just be the cherry on top of a great story. It is an inherent part of what helps to construct and animate the depth and psychological stratification we desire.

Anne Eekhout, Mary – or, The Birth of Frankenstein, translated from Dutch by Laura Watkinson, Pushkin Press, London, 2023, 352 pages

Anne Eekhout, Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein, translated from Dutch by Laura Watkinson, HarperVia, New York, 2023, 320 pages