When the First Queen of England Came from Flanders

Few Flemish women have played such a major role in political history and are nearly forgotten today as Matilda of Flanders. As the wife of William the Conqueror, she became the first queen of England as the result of the Norman Conquest. At a time when men were in charge, she was not afraid to make far-reaching decisions. Queen Matilda was important both in state affairs and in family disputes.

Matilda (ca. 1035-1083) is the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Flanders and Princess Adela of France. She married William, Duke of Normandy, in 1052 or 1053. In her early teens this was the normal age of marriage for high aristocratic women. Her father took her to the border of Normandy at Eu and handed over to William, who was accompanied by his mother Herleva and her husband Herluin de Conteville. The marriage ceremony took place in the Norman capital of Rouen. The first decade and a half of their marriage was a typical period in the life of an aristocratic couple. They had nine children, four boys and five girls, that gave them plenty of opportunity to be secure in the succession of Normandy and the arrangement of marriages with neighbouring rulers.

Queen Matilda in Agnes Strickland's 'Queens of England', 1882

Queen Matilda in Agnes Strickland's 'Queens of England', 1882This quiet life ended in the autumn of 1066 when William invaded England. In January his distant cousin Edward the Confessor had died. Long since childless, the English king may at one stage have promised the throne to William. By the early 1060s however he had changed his mind in favour of an English cousin Edgar. At the time of the king’s death Edgar was a twelve-year-old boy. This gave two rivals an opportunity to act. In England Edward’s brother-in-law Harold seized the throne, while in Normandy William remembered the English promise and reminded Harold that he had confirmed it. On the advice of his nobles and the pope in Rome, William put together an invasion force of approximately 1,000 ships and 8,000 men (Normans, Bretons and Flemish) as well as horses. In late September he crossed to England where on 14 October his forces killed Harold in battle. On Christmas Day 1066 at Westminster William was crowned King of England.

Golden child

Back in Normandy Matilda had been busy as regent jointly with their son Robert. In order to ensure divine support for her husband’s enterprise the couple had decided that their young daughter Cecilia should be offered to God as a nun to La Trinité at Caen. In June 1066 with the army and fleet almost ready, the contemporary poet Fulcoius compared Cecilia with the daughter of the biblical king Jehphtah, who had sacrificed his daughter in circumstances not dissimilar to those in 1066. He stressed that Matilda’s face was wet with tears. Matilda’s financial support was equally striking. The so-called Shiplist from the monastery at Fécamp, the logistical nerve centre for the invasion, detailed the number of Norman ships and knights gathered by William; it ends with a paragraph on Matilda:

‘The duke’s wife Matilda, who later became queen, in honour of her husband had a ship prepared called ‘Mora’ in which the duke went across. On its prow Matilda had fitted [a statue] of a golden child who with his right hand pointed to England and with his left hand held an ivory horn against his mouth. For this reason the duke granted Matilda the earldom of Kent.’

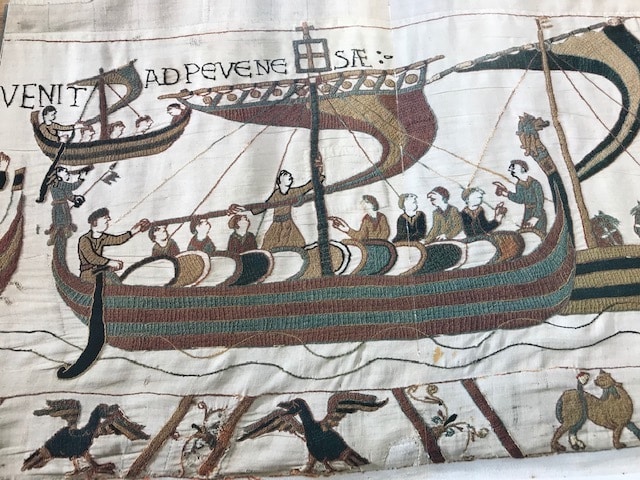

Detail of the Tapestry of Bayeux (ca. 1068) depicting the ship that Matilda of Flanders financed for the conquest of England in 1066.

Detail of the Tapestry of Bayeux (ca. 1068) depicting the ship that Matilda of Flanders financed for the conquest of England in 1066.William’s flagship with the golden child can be seen on the Bayeux Tapestry, the famous contemporary embroidery detailing the conquest, albeit in mirror image of the description given here. The motif of the golden child as symbol of a bright new future recalls a theme of the classical poet Virgil, recast by St Augustine as the coming of Christ. It was seen as a good omen for the invasion and also for Matilda’s pregnancy. Heavily pregnant with her youngest daughter Adela (born in January 1067) she could not attend William’s Christmas coronation or the February court when William handed out all the land in England to his followers. Kent, however, was on that occasion granted his half-brother Odo. Not until Easter 1068 did Matilda cross the sea for her own coronation at Winchester. Without precedent the liturgical laudes

(praises) placed the new queen in the company of four (male) apostles rather than the traditional (female) martyrs. Matilda was celebrated for her manly steadfastness at a time of great political drama.

Royal gossip

King William the Conqueror

King William the ConquerorIn Normandy Matilda’s eldest son Robert became increasingly impatient to succeed his father in the duchy. Unsurprisingly, William refused and their bitter stand off left Matilda caught in the middle. When matters had come to a head, a furious Robert left Normandy and sought exile with his mother’s kin in Flanders. Without her husband’s knowledge Matilda sent him secretly substantial sums of money. When William discovered his wife’s subterfuge he took his frustration out on her chaplain Samson, the poor messenger, who was forced to flee to the monastery of St Evroult. We know all of this because Samson’s fellow monk was no other than Orderic Vitalis, the famous Anglo-Norman chronicler who told us the royal gossip. He added that in despair about the rift between William and Robert, and uncertain about the future, Matilda had even consulted a Flemish prophet to put her mind at ease. Yet, this case seems to have been a rare disagreement. As her husband’s regent in a realm that stretched out on both sides of the Channel, she looked after affairs of state on whichever side William was absent. In England, as queen consort she issued charters, presided over court cases, rewarded loyal servants, and dispensed charity to churches and monasteries.

Yet, ties with her native country remained strong. She had kept in touch with her mother Countess Adela of Flanders and had asked her to bequeath a large estate in northern Normandy to the Norman nuns of Montivilliers. We do not know who conducted the negotiations but William the Fleming, Matilda’s steward, springs to mind. This William was not Matilda’s only compatriot who had followed in her wake to Normandy. She also invited various female cousins to marry William’s nobles: Beatrice of Valenciennes to Gilbert of Auffay and Gundrada of Oosterzele-Westerscheldeke to William of Warenne. That the weddings took place around 1066 suggests yet another way in which Matilda created Flemish alliances, thus drumming up military support for the conquest.

Statue of Matilda of Flanders by Carle Elshoecht (1850) in Luxembourg Garden, Paris

Statue of Matilda of Flanders by Carle Elshoecht (1850) in Luxembourg Garden, ParisDeath by mistake

Gundrada and her brothers Gerbod and Frederick, children of the voogt of St Bertin at St Omer, deserve a special mention because of the family’s massive contribution to the conquest. Gerbod excelled himself to such extent that he was briefly Earl of Chester (1067-71). Due to the civil war in Flanders after the death of Matilda’s brother Baldwin VI, Gerbod had to return home to defend his ancestral lands at the battle of Cassel. There he killed, apparently accidentally, Baldwin’s young son Arnulf of Flanders and was forced to end his life as a penitent monk at the Burgundian monastery of Cluny. Frederick may already have been in England before 1066 as he held land in Sussex. He distinguished himself especially in East Anglia for which he received large swatches of land in Norfolk. He was killed in c. 1070 by no other than the famous Fenland rebel Hereward the Wake.

Queen Matilda gave Gundrada, perhaps as a wedding gift, land in Carlton in Cambridgeshire. It is extremely rare to find gifts of land from English queens to women from their own country. Ultimately this land as well as all of Frederick’s English lands went to Gundrada and her husband William de Warenne, who in turn used it to support two monastic foundations dependent on Cluny with the wholehearted support of William and Matilda: Castle Acre priory in Norfolk and St Pancras at Lewes in Sussex. Given the charitable donations to this Burgundian monastery it remains surprising that neither Queen Matilda, nor for that matter Gundrada of Warenne, founded any monasteries in Flanders. Yet Flanders remained with them until beyond their death.

Queen Matilda is buried in the Abbey Church of the Holy Trinity (Abbaye aux Dames) in the French city of Caen

Queen Matilda is buried in the Abbey Church of the Holy Trinity (Abbaye aux Dames) in the French city of CaenWhen Queen Matilda died in 1083, her husband was desolate. The marriage had been an unusually happy one as William is a rare example of an English king without any illegitimate children. He buried her in the Abbey of the Holy Trinity at Caen in a tomb, which survives to this day, covered with a Flemish slab of black Tournai stone. Carved around all four sides is her epitaph. The Latin poem celebrates her Flemish descent, her royal blood, via her mother Adela as daughter and sister of kings of France, and her royal affinity as wife of the King of England. The material Flemish connection set a trend in England with Flemish immigrants being buried under Tournai marble: Gundrada at St Pancras in Lewes and Walter of Gent in Lincolnshire. In Matilda’s case it is a native touch to the final resting place of a remarkable Flemish woman.*

* Written as part of the project ‘The Literary Heritage of Anglo-Dutch relations 1050-1600’ (funded by the Leverhulme Trust 2018-21)