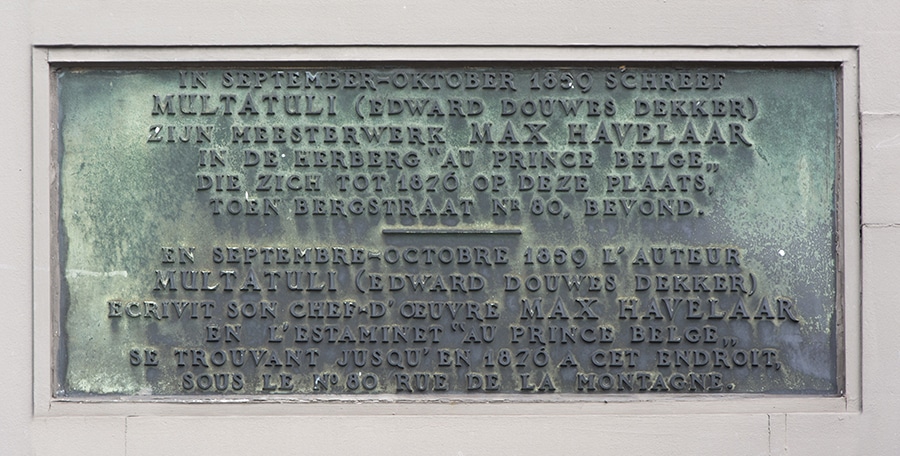

The building has gone, but a dusty plaque on the wall of a Brussels sandwich shop marks the site of the louche bar where the Dutch writer Multatuli wrote his classic novel Max Havelaar.

‘In September-October 1859,’ the bronze plaque reads (in Dutch and French), ‘Multatuli (Edward Douwes Dekker) wrote his masterpiece Max Havelaar in the bar Au Prince Belge that stood on this spot until 1876, at what was then Bergstraat 80.’

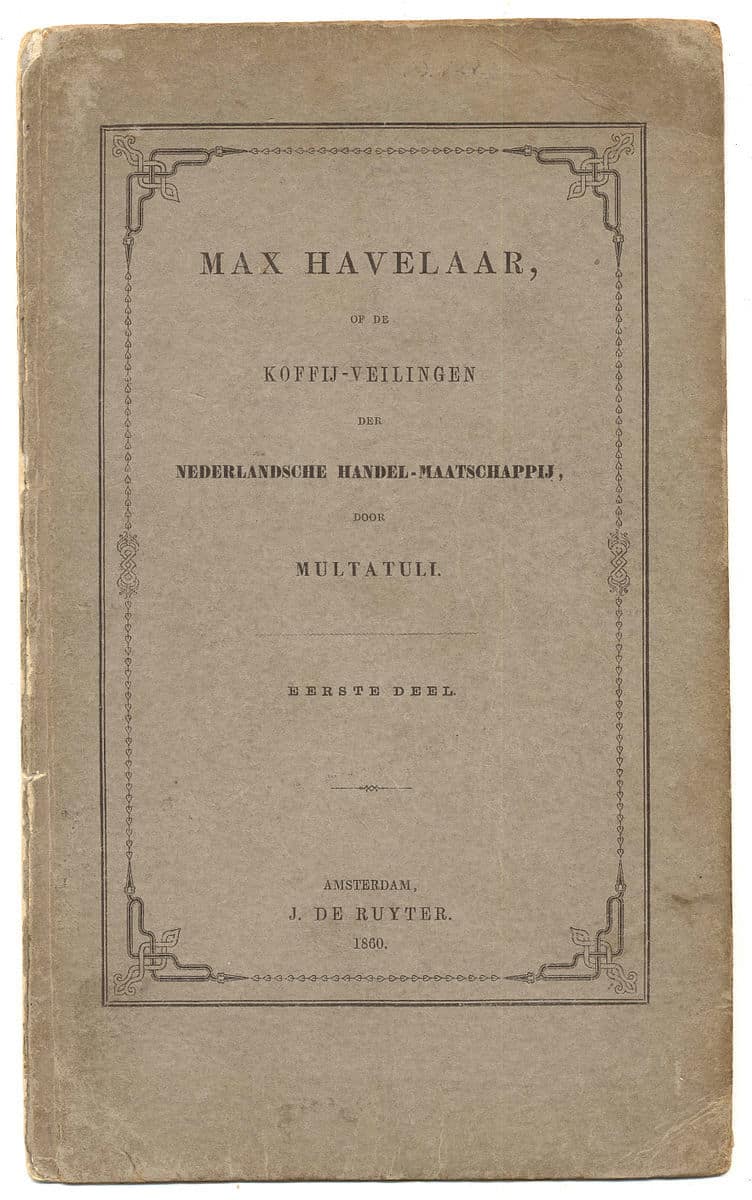

Cover of the first edition of Max Havelaar, J. De Ruyter, 1860, Amsterdam

Cover of the first edition of Max Havelaar, J. De Ruyter, 1860, AmsterdamThe book caused a scandal when it came out in 1860 because of its uncompromising criticism of Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia. Despite the long rather forbidding full title – Max Havelaar or, the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company – it is still read today in Dutch and dozens of other languages.

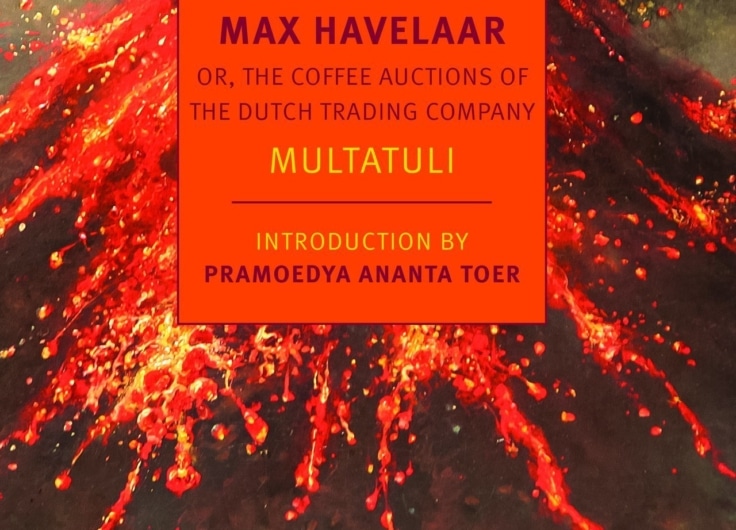

A brand-new English translation by Ina Rilke and David McKay came out a couple of years ago. The New York Times called it ‘a brilliantly inventive fiction that is also a work of burning political outrage.’

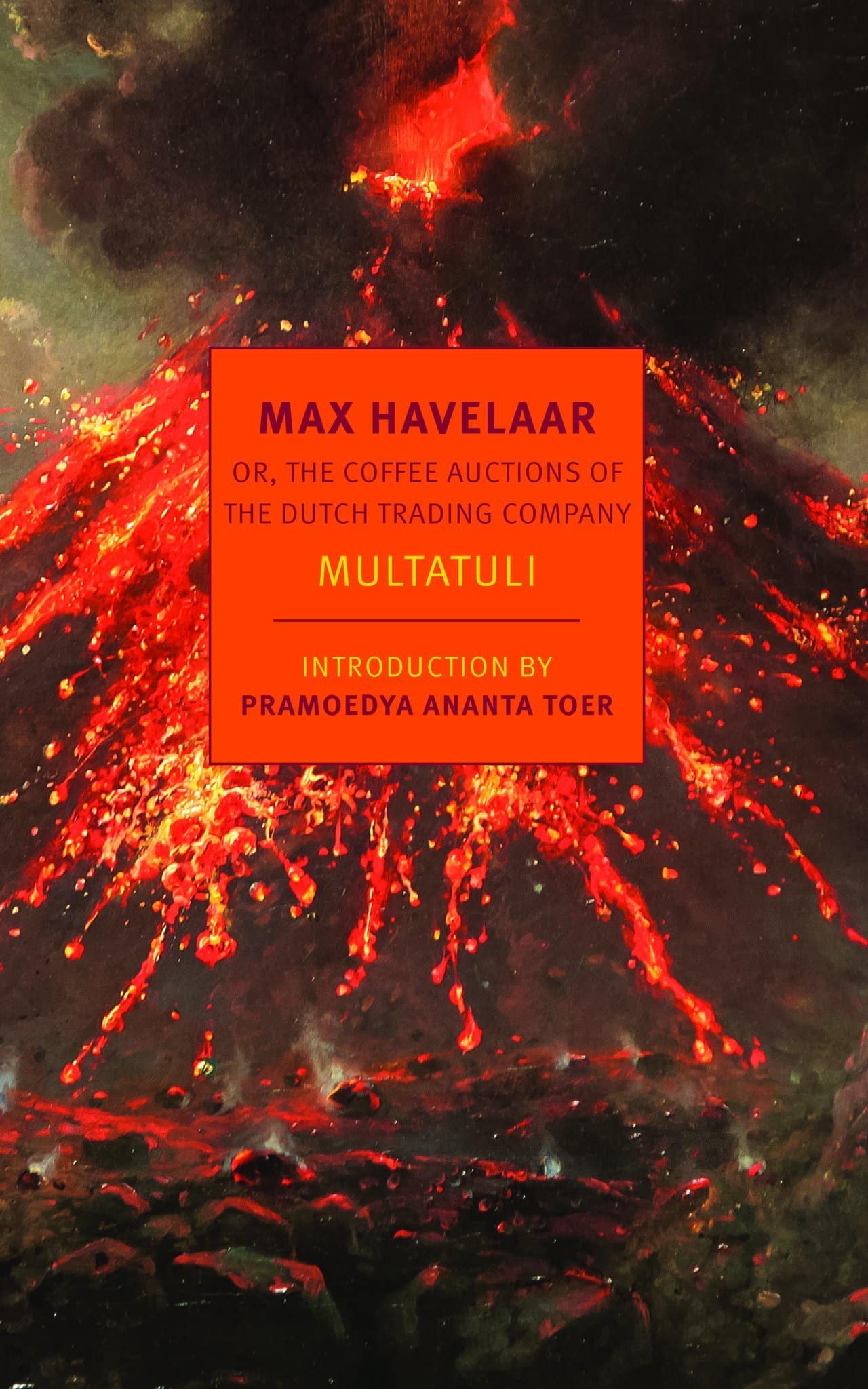

English edition of Max Havelaar, 2019

English edition of Max Havelaar, 2019But how many readers know that Multatuli wrote the book in an attic room above a rough Belgian bar where post office workers came to drink the local Faro beer? Everyone in the neighbourhood knew the strange Dutch writer who sometimes had to beg for coal to heat his garret room.

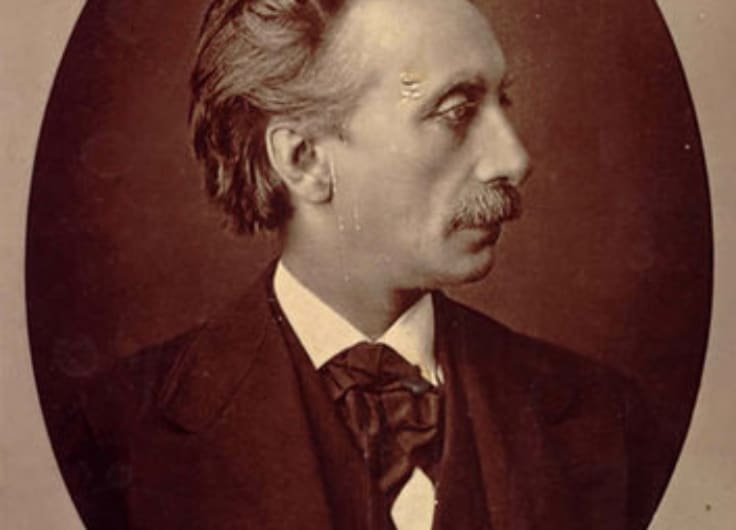

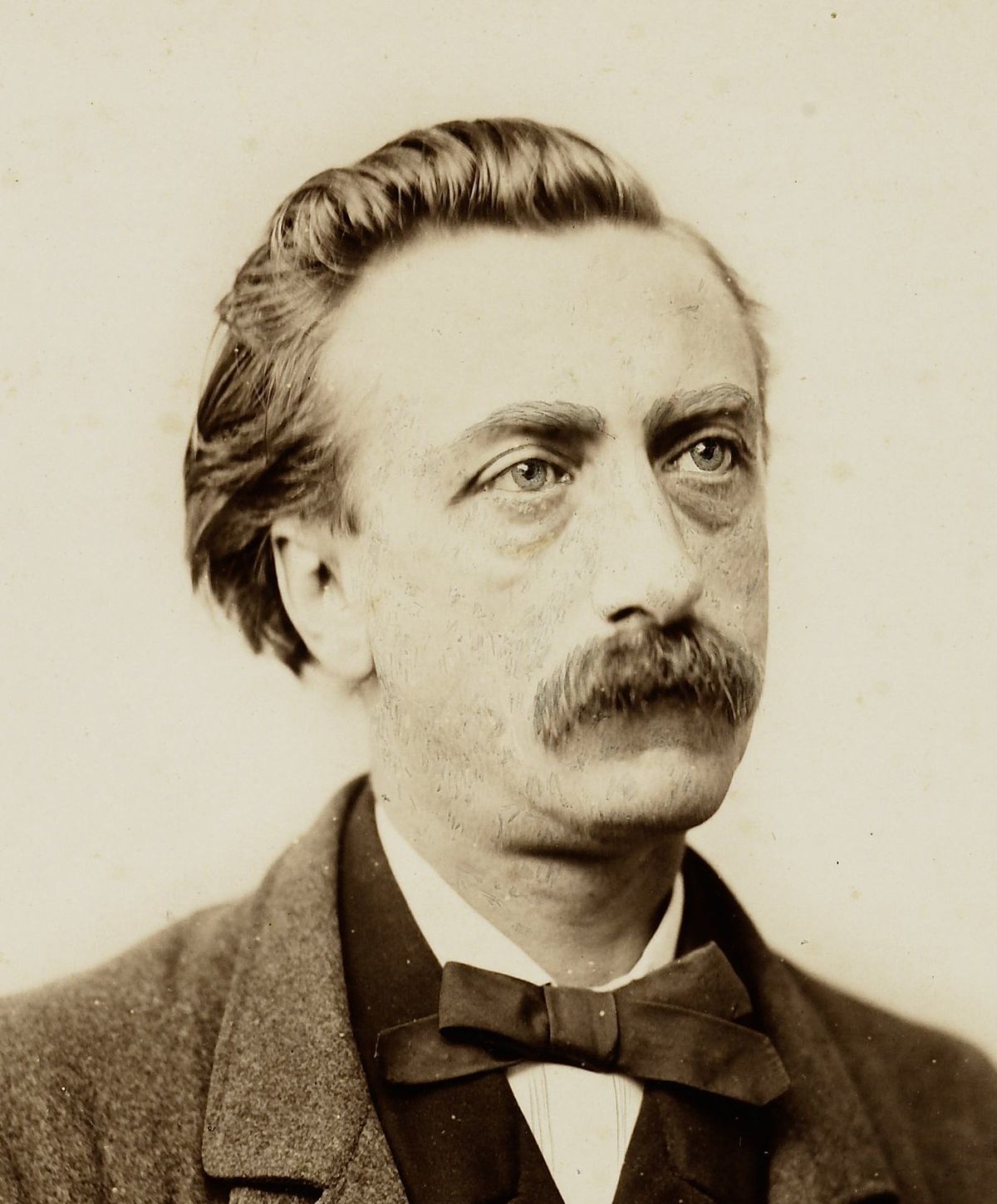

Multatuli (1820-1887)

Multatuli (1820-1887)The writer had fled to Brussels in 1857 to escape his creditors. He initially moved into a hotel opposite the Cathedral and found a job at the newspaper L’Indépendance Belge. He began writing Max Havelaar in September 1859 and finished it less than a month later. He was so poor that he had to beg for money to buy ink.

The novel has become a classic of Dutch literature, possibly the greatest Dutch novel of all time. It inspired the Dutch fairtrade coffee brand Max Havelaar and the radical Indonesian journalism initiative Project Multatuli. But the book might never have been written if it had not been for the warmth and hospitality of the people of Brussels who gave the author money to buy coal and ink.