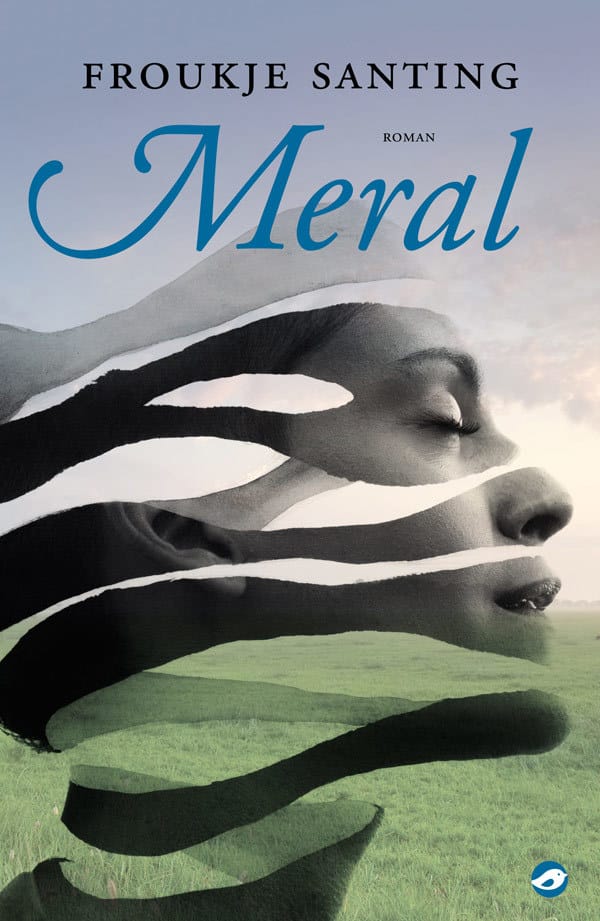

‘Meral’ by Froukje Santing: Torn Between Two Homelands

In Meral, author Froukje Santing subtly unravels the entanglements of a Dutch-Turkish family

It is not only the proverbial Young Turks who make their debut in Dutch Literature. A new career chapter is possible even for those who already have quite some writing experience. For many years, Froukje Santing (b. 1956) has written for the NRC Handelsblad newspaper, not least as a correspondent in Turkey, where she lived for 17 years.

Froukje Santing

Froukje Santing© Chris van Houts

After returning to the Netherlands, some ten years ago, she wrote about her reencounter with her home country after so many years, with Dwars op de tijdgeest (De Geus, 2012; Out of step with the zeitgeist). She studied World Religions and Islam in the Modern World and also co-authored Vechtscheiding

(De Geus, 2017; Acrimonious divorce), a book about how Turkish President Recep Erdoğan divides the Turkish community far beyond that country’s borders. And she continued to write for the NRC newspaper, and for De Groene Amsterdammer weekly magazine.

If Santing ever wrote a novel, Turkey and religion would likely play an important role. The theme may not come as a surprise, but with Meral, Santing illustrates how sometimes everyday reality is better described in fiction than hard facts. In a story, details surface that never make the headlines, but are nonetheless life-defining. Santing tells her story knowledgeably, with empathy and a dose of humour, in a calm style crafted by years of first-rate journalism. Poetic digressions are rare, but when used hit the mark.

Meral is a Turkish woman in her forties, a general practitioner in Amsterdam. She is married to Bilal, a labourer faced with losing his job. They have two children, Ismail and Esra, now almost grown-up. Meral came to the Netherlands at the age of four, Bilal just before the wedding. Their marriage is physically and intellectually an unequal one. According to Turkish tradition, marriage is not only a romantic but also an economic union.

Santing beautifully describes the tension between modern life, in which you can be both free and religious, and trying to keep the family together

While at work Meral is increasingly confronted by outward and other manifestations of religion in some of her Turkish patients, she also notices changes in her husband and children. For a while, Ismail finds a calling in the religious Gülen movement, then leaves it behind. To his own surprise, he falls madly in love with Rose, who with her red curls, blue eyes and fair skin could not be more Dutch. This creates tension within the family, especially with the traditional Bilal, who has come to glorify everything from his old homeland. He is bursting with homesickness, a gnawing feeling that often makes him aggressive.

For her part, the wise and sensitive Meral is also conflict avoidant. The strong, decisive Meral in the doctor’s office is very different from the quiet, overly obedient Meral at home. She conforms as much as possible to Turkish traditions, where macho men, sometimes full of resentment, are the boss. Santing beautifully describes this inner struggle that is bound up with tradition. Meral recognises the same tension in Ismail: torn between modern life, in which you can be both free and religious, and trying to keep the family together. All of them feel lonely, inadequate, and Meral increasingly thinks back to the dreams and values of her father, who was so proud that his young teenage daughter could go to medical school.

In a way, it was easier for her father to bridge the gap with the Netherlands, to get used to the customs in his new country. Her husband Bilal withdraws, would rather be in Turkey, where every year, during the summer holidays to his village, he perks up. There he can drink coffee and tea with the other men and spend hours discussing politics.

You are never rid of your origins, and migrants especially are not allowed to forget them. At times, that background may become a stigma. You have a responsibility towards your community, both in your new country and in your country of origin. But you also want to move forward, with the times. And all the while, everyone is judging you.

Santing subtly incorporates all those dilemmas, all those doubts, all those difficulties and trade-offs in her debut. The novel reads like a portrait of an era, describing what life is like for a Turkish Muslim in the West. And how that changed post 9/11, and then again after the failed coup against Erdoğan in 2016 for the Turkish community in particular, when the president started to behave even more like a TV kingpin.

The story comes to a gripping close in the cemetery of Kayseri in Turkey, where Meral’s father is buried. Finally, Meral must decide on a course of action that will shape her life and that of her family. Possibly she will regain her zest for life as a result, but that will not be straightforward. Just as nothing in life can be taken for granted, certainly not in the life of a migrant woman.

Excerpt from ‘Meral’, as translated by Paul Vincent

pp. 62-63

On the last stretch of unmetalled road towards the village Meral’s body rocks silently in response to the potholes in the dry sand. Ignoring the stifling heat that billows into the car, she keeps the button pressed until the side window has completely rolled down. How often has she absorbed this panorama? More often than she can remember. The green, yellow and dark-brown smudges of bare mountains, trees and fields, houses and a minaret, carelessly strewn around in the sparsely populated Anatolian interior with its bone-dry summers and in the winter the snow-swept into drifts as far as the eye can see. But you must love even a landscape. Without love no meaning.

As so often after one of her husband’s outbursts she knows rationally that she should have spoken her mind to Bilal. She should have begged him, no, ordered him not to drive off without Ismail. But again she had opted for the easy way out. Though she should have thrown her full weight behind her son, she had swallowed her dissatisfaction and sadness.

In her grey despondency, every village merges before her eyes into a copy of the villages that are familiar to her. Her father’s village, where she too was born and lived until the age of five, her mother’s, Bilal’s home village. After the inhabitants, with reckless courage, have gone to the city or further afield to Europe, the silver-green poplars rustle without all that many promises. Their ghosts haunt the new houses that they have built in their home villages with the money they have scraped together there. Comfortable, detached houses with several storeys, surrounded by spacious fenced-off gardens. Anyway, the children would return. But contrary to expectations their children seldom came. What is there for them to do in a village? The parents stay a few weeks at most, a few a little longer. Their old-fashioned clothes – the men in short, hand-knitted buttoned overcoats and their woollen caps regardless of the time of year, the women in knickerbockers and shapeless pullovers that accentuate their over-ripe breasts – confirm that with their departure they also stopped their inner clock.

‘What do you think Ismail means by: I promise I shall let myself be found?’ Esra asks after a while.

Bilal looks sideways at Meral. As he shunts the car into a higher gear, he snorts in irritation.

‘What do you think?’ says Meral, bouncing the question back to Esra.

‘I think it’s a letter asking for forgiveness. He’s sorry about his question.’

‘Being sorry is all very well,’ growls Bilal. ‘He’s not a child any more and he still has no idea about relationships.’

‘Perhaps he didn’t mean to be so rude,’ replies Esra.

For minutes it is silent in the car, until Esra comes up with a new question from the back seat: ‘What do you think, are we going to see Ismail this vacation?’

Froukje Santing, Meral, Uitgeverij Orlando, Amsterdam, 224 pp.