By paying attention to urban culture at large, the MIMA in Brussels opens itself up to a young and hip generation. The Millennium Iconoclast Museum of Art wants to present “cultural history 2.0”, with special attention for talent that has been pushed into the margin. In order to do so, the museum has been rethought as a computer game.

The Millennium Iconoclast Museum of Art

The Millennium Iconoclast Museum of Art© MIMA

The MIMA is not your average art space. The museum is housed in the former Belle Vue brewery, in the heart of Brussels in the municipality of Molenbeek, once branded a ‘hellhole’ by the American president Trump (the museum itself uses the term as a badge of honour). The MIMA is the brainchild of Michel de Launoit, son of the late count Jean-Pierre de Launoit, banker and former president of the Queen Elisabeth competition. MIMA’s captain calls himself a cultural entrepreneur. The MIMA is independent and made sustainable through crowdfunding and ticketing.

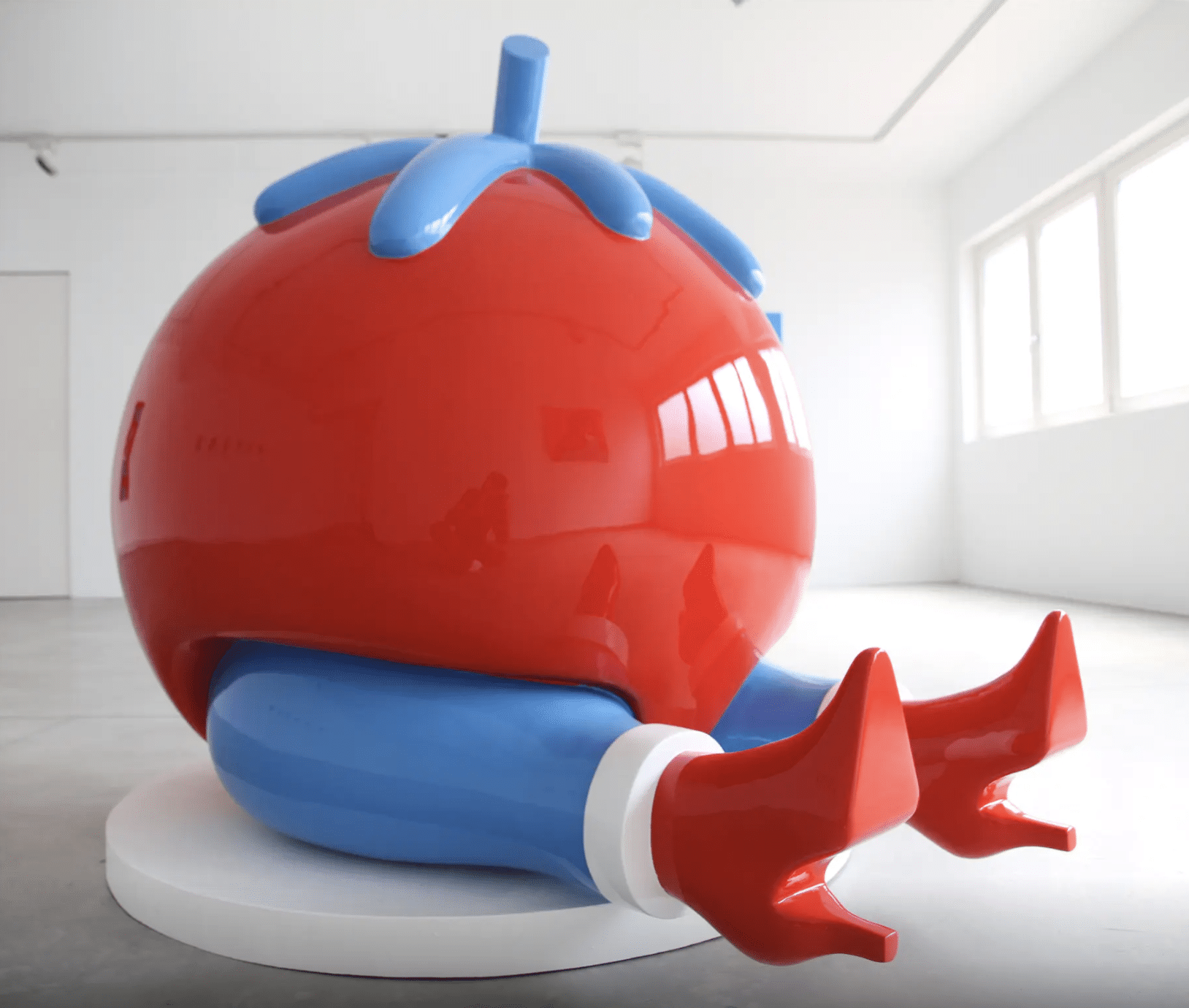

Parra, Give Up, 2015

Parra, Give Up, 2015© MIMA

The museum is not yet a part of Brussels’ art institution or gallery establishment but, through countless (media) partnerships, wants to provide a platform specifically for the younger generation. Up-and-coming talent with a high ‘urban-feel’ is given space. In particular graffiti and street art, graphic design, music (punk-rock, electro, hip-hop, folk), sports (skateboarding, surfing, extreme sports), geek culture and other artforms (film, plastic arts, performance, comics, tattooing, styling) are of interest to the MIMA. By offering a program that reflects contemporary youth culture the museum wants to attract a new and diverse audience.

The space is divided in eight polyvalent exhibition areas. On the top floor you can find the permanent collection, with around forty works that are on loan, or donations from national and international artists who have taken part in past thematic exhibitions.

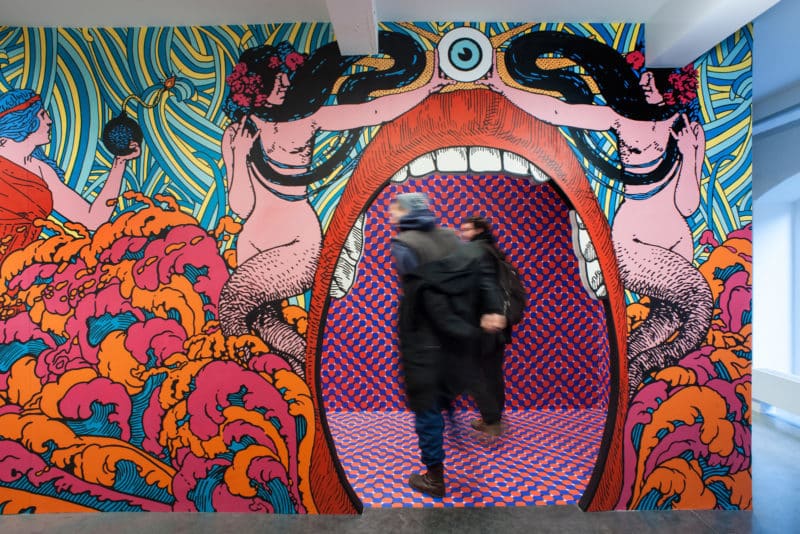

Installation by Maya Hayuk for the exhibition City Lights, 2016

Installation by Maya Hayuk for the exhibition City Lights, 2016© Roselinde Bon

No pretentious explaining

Their mission statement mentions it explicitly: people nowadays barely share any references, everyone has a different background and their own opinions, while we are all insatiably searching for information that we have unlimited access to. The MIMA would like to speak to this ‘uninformed’ audience. And what is more contemporary than capitalizing on the ‘gamification of knowledge’? Therefore, the entire museum has been set up as a computer game, with an easily accessible starting point and a high-level exit. You literally move through a variety of spaces and ‘levels’, gaining experiences along the way as you are confronted with art works deployed as ‘obstacles’.

Boris Tellegen, Untitled, 2016

Boris Tellegen, Untitled, 2016© MIMA

The intention is to unpack the complexity of ideas, by virtue of your participation in a game, your immersion in the art works. Doubtless attractive for those who associate ‘museum’ with ‘boring’ and for whom absorbing lofty explanation or background information quickly becomes exhausting. Any textual interpretation is given in French or English, and there is no audio-guide or leaflet. ‘Discover it yourself’ seems to be the formula, which is embraced by the many young visitors (amongst them many tourists staying in the hip Meininger Hotel close-by). Not too much context, not too much reflection; just colours, shapes, discoveries and letting the experiences guide you. Iconoclast, quoi.

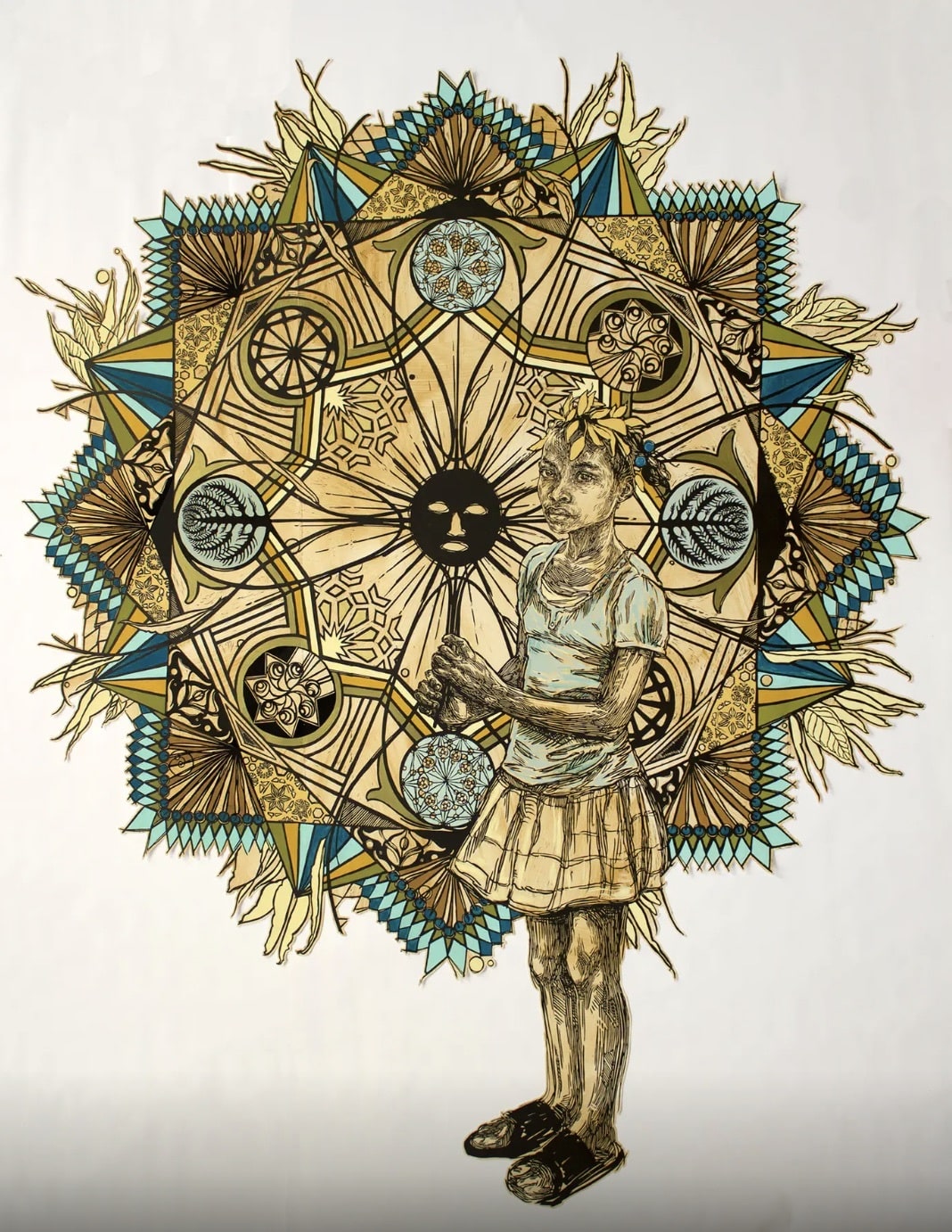

Swoon, Edline, 2015

Swoon, Edline, 2015© MIMA

The MIMA’s curators/artistic directors are of the opinion that technology has changed artistic language drastically, shaping it in an ‘increasingly interdisciplinary, emphatic and collaborative’ way. That sounds great and is doubtlessly correct, but as a statement it remains fairly abstract. It is remarkable that these supposedly influential technologies are relatively absent. Except if they primarily refer to the Internet, because the art works on show are largely classical: drawings, sculpture, ceramics and installations.

In terms of content the museum curates an exhibition every six months that engages with contemporary social themes such as collaboration, identity, ecology, freedom and humour, civil disobedience… This summer saw the last of Dreambox, an at times psychedelic sequence of spaces in which optical illusions, interactive musical installations and visual art encouraged both dreaming and reflection. Yet the lack of any further context made it hard to follow any specific narrative. At times you can find panels with information in three languages (sometimes awkwardly translated) that give some additional insight into the work and the artist. Yet the specific reasoning behind why exactly these works are placed in relation to each other remains fairly unclear.

Most pieces exist in isolation, placed together without any interconnection, randomly. It feels gratuitous, but maybe it is meant as a commentary on contemporary society, in which people lives disconnected lives? Or maybe it is a response to our habitual need for grand narratives, to look for an expressly crafted connection that is being disrupted. Iconoclastic, you know.

Dream Box, Elzo Durt, 2019

Dream Box, Elzo Durt, 2019© MIMA

Molem is art

Flashing, zapping, scrolling, recognizable and stimulating. Yet how much actually sticks, what remains after the visit? According to the MIMA, the museum is tapped into contemporary ‘urban culture’, launching the offensive against an establishment that represses grassroots and street artists. A noble stance, but too meek to really count as an attack on the status quo. The works shown are, without a doubt, meaningful, forward-thinking and in some instances critical, but the larger issue at stake here remains obscure.

Part of the exhibition Get Up, Stand Up, 2018

Part of the exhibition Get Up, Stand Up, 2018© MIMA

This ‘museum for the hip and young generation’ wants to push a “cultural history 2.0” to the centre stage, shifting the focus somewhat. Very admirable and it is nice that the MIMA succeeds in tactfully lowering the barrier to art for general audiences. For a lot of Brussels’ young people, the MIMA is their first introduction to ‘white cube’ art, even though they’re also unwillingly signing up for the gentrification of this side of Molenbeek.

The intention to offer an ‘alternative art history’, as promised when the museum opened, seems to have largely been abandoned. Don’t expect a consistent narrative on art and interdisciplinarity or a decolonialized or feminist perspective on art history. The art presented here is placed (for the time being) largely outside of the circuit of major museums, galleries or auction houses. It is a cheerful, at times refreshingly cheeky, at other times shallow mix & match of emerging urban talent with a very Brussel-esk touch, in every sense of the word. At times funny, at times critical, at times incoherent but most of the time surprising.

Part of the exhibition Obsessions, 2019

Part of the exhibition Obsessions, 2019© MIMA

When Kanal, the cousin of the Centre Pompidou in Akenaai reopens after an intense period of renovation, it might mean the return of affordable combination tickets that grant access to both museums, as they operate, almost literally, in the same realm. Obsessions will have to prove if MIMA is going to be permanently able to capitalize on urban life and grow roots in the cultural scene of Brussels. With the proximity of LaVallée and Recyclart, the art scene of ‘Molem’, the so-called Bronx of Brussels, is building bridges to new audiences and new approaches.