During his daily commute, editor-in-chief Luc Devoldere drives by several works of art scattered alongside the motorway: Fabre and his cross, a bit of chaos and a scowling Cyclops. Admiring these pieces from his car, he lets his mind wander…

Confession time: For over twenty years, I have been driving to work on my own, along an eighty kilometre stretch of motorway. I leave my home in the suburbs of Brussels – a place called Aalst –, and head to our offices, which are located somewhere between Kortrijk and Lille, near the Belgian-French border.

In Ghent, I take the motorway that leads from – let’s take a broad perspective – the North Cape to the Mediterranean Sea, and they won’t let you forget that. Loads of lorries drive along those roads, and, as soon as spring is in the air, swarms of Dutch people slowly but steadily start moving south; Gray-quiffed pensioners take the lead, soon followed by camper vans and family cars.

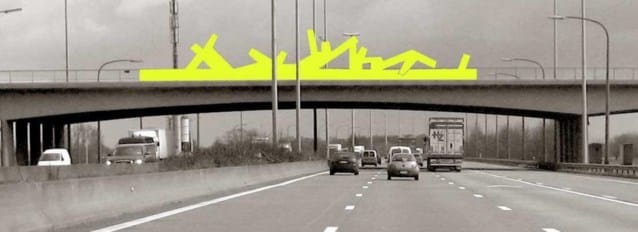

The work 'Chaos collision 1996' along the E17 highway in Deinze

The work 'Chaos collision 1996' along the E17 highway in DeinzeBarrier between home and work

Green pastures and industrial sites zoom past. In the distance, bell towers arise dreamily. Once in a while you might pass some road kill, an unfortunate cat or a rabbit. If you turn to the side, you can see your ‘brothers in traffic’: a man typing away on his smart phone, a woman applying make-up with an eye pencil while still managing to keep to her lane, a smoker driving in a jerky fashion, windows down.

Now and then, you may end up in a traffic jam. One is never quite sure what exactly sets them off, or what makes them dissolve. You drive past cars that have collided and have been brought to a complete standstill in a state of considerable distress. A lonesome person in a yellow vest is making a phone call on the shoulder. All of a sudden you find yourself rubbernecking, slowing down to take a glance at the driver involved in the accident at the other side of the motorway. You might tune in to Klara, or treat yourself by letting a guilty pleasure à la Laura Pausini sing at the top of their lungs in your cabin. This way, you dream up your own barrier between your home and the workplace.

But for now, I would like to turn to the works of art by the side of my stretch of motorway.

Do we all have our cross to bear?

A few months ago, not that far from Wetteren (between Aalst and Ghent, next to the E40; just look to your left as you pass the bridge for cyclists – if your travel companion lets you, that is), a work of art by Jan Fabre appeared.

It is called De man die het kruis draagt (The man bearing the cross). It represents the artist himself, literally glowing – as the statue is gold-plated –, standing upright wearing his infamous long coat. Like a juggler, he is balancing a large gilded cross in the palm of his hand. Through the glasses on his nose, he stares intently at the cross in front of him.

'The man bearing the cross' by Jan Fabre along the E40 highway.

'The man bearing the cross' by Jan Fabre along the E40 highway.© Jan Fabre

Back in 2015, the statue was placed in the Antwerp cathedral. The church believed it represented the role of the visitor. After all, people of faith experience a similar balancing act as they try to determine their position vis à vis the cross’s skandalon.

Jan Fabre is known for being physically present in his art. He features on a step ladder on top of the roof of S.M.A.K, the Ghent museum for contemporary art, as De man die de wolken meet (The man who measures the clouds). We can also recognise him in the gardens of the Gezellemuseum in Bruges as De man die vuur geeft. (The man who gives fire): Hidden away under his gilded coat, barefoot – his shoes a little further, atop a pedestal –, he passes a light to… Well, to whom indeed?

'The man bearing the cross' by Jan Fabre in the Antwerp cathedral

'The man bearing the cross' by Jan Fabre in the Antwerp cathedral© Jan Fabre

Every time I drive past the statue with the big cross I give it a quick gander. I only seem to do so during my commute from Aalst to Ghent, and my eyes have to scan the far side of the motorway. What I saw one morning in spring was nothing short of an epiphany. The quivering early-morning mists of this spring day almost completely hid the base of the windmill, which stands at about fifty metres behind the statue. All I saw was three beams; A cross, flying freely in the air. Did anyone consider this effect possible, since the gold-plated man is almost presenting the cross to the windmill behind him? Whatever the case may be, this unwanted ephemeral “installation” now seems imbued with a touch of magic.

However, I cannot stop wondering about the company’s governing board (a training centre of the Robotic Surgery Institute ORSI) that decided to place the statue there in tempore non suspecto, i.e. before Jan Fabre was caught up in the tornado of public shame we have come to associate with each #MeToo–scandal. It is the choreographer, not the visual artist, who has been accused of inappropriate behaviour towards his female dancers/employees.

I cannot stop wondering about the company’s governing board that decided to place the statue there in tempore non suspecto

Maybe one of the board members now believes the sculpture should never have been planted there. Incidentally: Can we still play Michael Jackson songs on public radio, or tolerate Leopold II statues in the public domain? In my opinion, we can. Yet, this statue always reminds me of this ongoing debate. Meanwhile, Jan Fabre is bearing his cross – apparently, devastated by the commotion, he chose to do so abroad. It is highly likely he had been living in his own bubble for way too long, worshipped by the groupies he surrounded himself with. It must be tough to wake up and realise you are part of a cult.

The work 'Chaos chain collision 1996' along the E17 highway in Deinze

The work 'Chaos chain collision 1996' along the E17 highway in DeinzeNone of this applies to the second work of art that crosses my path, near Deinze, somewhere in between Ghent and Kortrijk. An unsuspecting passer-by might not even realise it is in fact art. The large yellow construction, with its irregular, jagged edges, is about thirty metres long and is suspended from the side of a motorway bridge. Although it might remind you of a mountain range or a portion of fries, the work actually commemorates the dramatic pile-up that occurred on 27 February 1996. On that day, thick fog – which is actually not uncommon in the Scheldt river valley – set in quite suddenly. In mere seconds about two hundred cars crashed into one another, resulting in a graveyard of twisted metal. Ten people lost their lives. Fifty-six others suffered major injuries, wile thirty more had to be treated for minor injuries.

In fact, this piece, entitled Chaos kettingbotsing 1996 (Chaos chain collision), is a Mahnmal, i.e. a warning directed to motorists to drive more safely. You could compare it to those rather moralising verbal messages popping up alongside Flemish roads, which are replaced every so often by yet another one. And would you believe it? That message is, “Je hebt kijken en je hebt kijken kijken”, i.e. “there is looking, and there is truly seeing.” This quote was taken from a particularly eloquent Temptation Island contestant, who would – predictably – succumb to this distinction himself.

The cyclops of Marco Boggio Sella in Ghent and along the E17 highway in Waregem

The cyclops of Marco Boggio Sella in Ghent and along the E17 highway in WaregemThe forklift Cyclops

Finally, just a few minutes’ drive from Waregem, we encounter the Cyclops: An enormous, hideous, naked, one-eyed giant, who scowls at the passing commuters. This sculpture by Marco Boggio Sella once overlooked the streets of Ghent as part of the open-air exhibition Over the Edges (2000). Now, having been bought by forklift producers H&M International, we find him stranded on top of a forklift.

Every once in a while a concerned parent, chauffeuring the kids around, will object to the Cyclops’ full-frontal nudity. However, whenever the Belgian Red Devils are getting ready for a big game, this oversized garden gnome is dressed up in a football shirt and shorts featuring the colours of the nation’s flag. Each time I lay eyes on him, I see Odysseus, cunningly thrusting a pointy wooden stake, hardened in the fire, through the giant’s eye, allowing him to escape, and return to his beloved Ithaca.

There is looking, and then there is truly seeing.