Nature Doesn’t Cause Disasters, People Do

In her monthly column, cultural historian Lotte Jensen looks at current events through the lens of history. In the first episode, she recounts how she has seen the consequences of climate change with her own eyes. But what causes natural disasters? History leaves us in no doubt.

19 July 2021. A few days after the disastrous floods in Limburg, Belgium and Germany I rode my bike along the Waal River near Nijmegen to see how high the water was. The floodplains were completely submerged and the Grote Altena campsite near Oosterhout was flooded. It’s true that the water was even higher last February. But it was winter then. Now it’s the middle of summer and the rivers should not have overflowed their banks. This year’s extremely heavy rainfall has led to untold human suffering and material damage.

From the campground, I cycle back towards Nijmegen. To my right I see pieces of wreckage drifting by. The Waal glows darkly brown. On the left, I see new houses being built right behind the dike and I wonder – involuntarily – how that will work out. Hopefully, this time, the rivers have been allotted sufficient space to accommodate rising water levels in the future. They hadn’t been in 1995, when a quarter of a million people were evacuated from the Gelderland River area.

After the floods, both the Dutch and the Belgian royal couple visited affected municipalities.

After the floods, both the Dutch and the Belgian royal couple visited affected municipalities.© Screenshots Twitter

After the floods this summer, relief efforts started immediately: the Dutch and Belgians donated generously to help their affected compatriots. There was also royal sympathy. The Dutch royal couple visited hard-hit Valkenburg, while the Belgian king and queen waded in their wellies through the streets of Pepinster. King Filip was visibly shaken during the national commemoration on 20 July. In his speech a day later, he called the floods an ‘unprecedented natural disaster’.

In a thought-provoking article in the daily De Morgen, University of Antwerp historian Tim Soens posited that the Belgian king misspoke when he used the term ‘natural disaster’. That terminology suggests that these events are somehow apart from humankind, but in fact, the changing climate is a direct consequence of human activity. A recent study shows clearly the direct relationship between the July floods and human activity. Soens argues that the Vesder Valley disaster was the result of two hundred years of ‘reckless river management’. Industrialists made the decision to settle in areas along a river with significant flood risks. In short, humans are responsible for this flood, not nature.

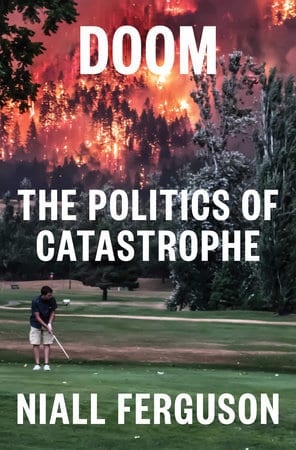

The British-American historian Niall Ferguson goes a step further. In Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe (2020)

he asserts that all disasters have been caused by humankind. Whether it’s famine, a plane crash, an earthquake or an epidemic, human action is always a determining factor. Decisions to settle permanently in potential disaster areas (near volcanos, rivers or fault lines) result in natural disasters. If a river overflows its banks, but nothing or no one suffers as a result, it is not a disaster. Politics also play a substantial role. Whenever governments act or fail to act, minor disasters can turn into major catastrophes. Ferguson explains that the Irish famine in the 1840s was disproportionately severe because the government did not intervene. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Soviet system also spawned several large-scale famines. Disaster and politics are always inextricably linked, says Fergusson in his very readable book.

the Waal River near Nijmegen

the Waal River near Nijmegen© Edwinek via Flickr/ CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

A month later I cycled again along the Waal in Nijmegen. The water glistened blue-green. I drank my coffee, as usual, on the terrace of the Grote Altena campsite. Children were playing football on the floodplain. Everything looked peaceful.

But looks can be deceiving. Less than a hundred and fifty kilometres away, victims and their relatives are still struggling with the aftermath of the floods. Such a disaster, according to climatologists, only occurs once every 400 years. They can’t predict when the next one will occur, but it could be next year.

The painful lesson that history teaches us is that all the catastrophes are caused to a greater or lesser extent by us. The good news: we can also work to avoid such catastrophes in the future.