Never Sell Shell: A History of Royal Dutch Shell

Royal Dutch Shell is an icon of twentieth-century business culture. In 2007 that was marked with the publication of its history.

In 2007, Royal Dutch Shell plc marked its centenary with the publication of a four-volume history of this global oil company by a team of economic historians from the University of Utrecht. They have subdivided this history into three lengthy periods – from the 1890s up until 1939 (vol 1), through the Second World war to the oil crisis of 1973 (vol. 2), and from 1973 to the present (vol. 3). The final volume contains a chapter on the many documentary films produced by Shell, plus a range of interesting appendices: statistics on oil production from 1881 to 2000; the names of all managing directors, board members and non-executive directors; a collective bibliography and an index for the set as a whole. The four volumes have been lavishly illustrated, and this extensive pictorial record has its own and very fascinating story to tell of Shell as an icon of twentieth-century business culture.

A century ago, this Anglo-Dutch joint venture came into existence through the amalgamation of the British Shell Transport Company, established in 1897, and the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company, founded in 1890, which was one of a very few companies – KLM Royal Dutch Airline is another – to be awarded the predicate ‘Royal’ right from the start. Today Royal Dutch Shell is a global operation, with 90,000 employees in 140 different countries, an annual turnover of £318 billion (in 2005), and a total capitalisation of £139 billion (in 2000). It is not only one of the largest, but also one of the most profitable companies in the world. Over the past century, the average annual return on shares has always been above 15%, providing a solid base for the old stockbroker’s saying: ‘Never Sell Shell’.

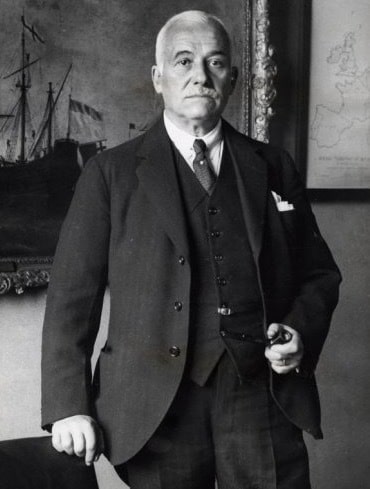

Sir Henri Deterding

Sir Henri DeterdingShell

In volume 1, From Challenger to Joint Industry Leader, 1890-1939. Joost Jonker and Jan Luiten van Zanden present what is very much the story of the Dutch tycoon, Sir Henri Deterding – the ‘Napoleon of Oil’ – whose single-minded determination and sound business instinct not only led to the merger of 1907, but also took the company from its colonial roots in the former Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) and its reliance on the Asian market to being, by the 1920s, the largest oil company in the world, a business enterprise that controlled the whole supply chain from production, transport and refining through to marketing, selling and the distribution of the final product to consumers all over the world. In 1928, in order to stabilise the world oil market, Deterding negotiated the secret Achnacarry agreement with his main competitors in the USA, on the basis of the Dutch principle ‘co-operation means power’. By the time he retired in 1937, a strategy of worldwide expansion – into the Middle East, Siberia, the United States, Mexico and Venezuela – had ensured that Shell always had sufficient resources elsewhere when it needed them, enabling it to overcome major mishaps such as the closing of its Russian oilfields after the October Revolution in 1917, the nationalisation of the Mexican oilfields in 1938, the loss of Romania to the Germans in 1940 or that of the Dutch East Indies to the Japanese after 1942.

This first period – or at any rate the years covering what is known as the Second Golden Age of the Netherlands, from 1890 to the First World War – had already been described half a century ago in three massive volumes by the Dutch colonial historian F.C. Gerretson, who had served as secretary to Deterding and Hendrikus Colijn (who became CEO of Royal Dutch Shell in 1925 and served five times as Prime Minister of the Netherlands between 1925-1926 and 1933-1939) in the 1920s. Gerretson’s history is a tale of adventure in the Eastern seas, and many of his pages could have come straight out of Joseph Conrad, some of whose novels were equally set in the Malay archipelago of the 1890s. As Gerretson saw it, Deterding’s enterprise and the principles of liberal capitalism were the key to the phenomenal rise of Shell. In 2008 Gerretson’s archive will be opened to historians, and one might hope that a biography will now be written of this man, who was one of the shrewdest operators in Dutch politics in the first half of the twentieth century while at the same time he always remained attached to Shell.

Shell’s colonial roots are exemplified by the Loudon family, who for generations have occupied a central place within the Dutch establishment – from James Loudon, who as governor-general of the Dutch East Indies started the war against Aceh in 1873, through his son Hugo Loudon, who in the 1890s negotiated a crucial contract with the local ruler for the Perlak oil field in Aceh and from 1902 until 1941 was one of the key leaders of the company; to his grandson John Loudon, who was chief executive of Shell from 1947 till 1965, then chairman of the supervisory board till 1976; and finally his great-grandson Aarnout Loudon, who after a distinguished career in Dutch business served as a non-executive director of Royal Dutch Shell from 1997 to 2007. This dynasty of oil barons, bankers, captains of industry, ministers, ambassadors and colonial officials is the nearest Dutch equivalent to the Rockefellers – and they surely deserve a monograph of their own one day.

Volume 2, Powering the Hydrocarbon Revolution, 1939-1973, by Stephen Howarth and Joost Jonker, opens with an informative chapter on how Shell came through the Second World War. When German paratroops landed near The Hague in May 1940, one of the last fishermen to leave Scheveningen harbour was hired by Shell to take its priceless oil maps and some ten million guilders in gold to London and Curaçao, from where the company managed to pull through, ending the war in much better organisational shape than before. For, in contrast to the Deterding era, the company was now run by a Committee of Anglo-Dutch Directors – a system reminiscent of the former East India Company in London, which for a long time had two Dutch directors on its board.

A shell barrel in Port Harcourt, Nigeria

A shell barrel in Port Harcourt, NigeriaAfter the war, during the 1950s and 1960s, the oil industry as a whole greatly expanded; oil overtook coal as the main source of energy; and the Middle East became the most important oil-producing area. During this period Shell managed to maintain a very strong position in global competition, thanks to its decentralised international structure and its many partnerships, its large fleet, its many local refineries and the innovative petrochemical research carried out in its laboratories.

In volume 3, Keeping Competitive in Turbulent Markets, 1973-2007, Keetie Sluyterman relates how Shell – which by the 1970s had been one of the two largest oil enterprises in the world for over fifty years – managed to overcome the oil crisis of 1973, when Middle Eastern governments nationalised their oilfields and established OPEC, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries, in order to get a bigger share of the immense oil profits.

This volume also relates how from the 1980s onwards Shell dealt with a series of political campaigns – about the boycott of Rhodesia, the Apartheid regime in South Africa, and the plight of the Ogoni people in Nigeria and the environmental damage they suffered as a result of oil production. This came to a head with the trial and hanging of the writer Ken Saro-Wiwa in 1995. No less damaging was the public outcry, also in 1995, when the company announced its intention of sinking the redundant Brent Star platform in the North Sea oilfield, where Shell had been very active especially after the collapse of world oil prices in the 1980s. All this had a negative impact on Shell’s reputation as a company.

In response, Shell engaged in a dialogue with its critics, in particular Greenpeace, Amnesty International and Pax Christi, and in 1997 revised its Statement of General Business Principles to include not just the importance of profit and the market economy, but also reference to human rights, sustainable development and the company’s responsibilities to society. This was backed up by a system of controls and the establishment of the Shell Foundation with an initial endowment of $250 million for its two key programmes, Sustainable Energy and Sustainable Communities. At the same time, in response to changes in market conditions, the revolution in information technology and the rise of the global economy, from 1998 onwards Shell embarked on a major overhaul of its organisational structure. In 2005, abandoning the old committee structure, the group was consolidated as Royal Dutch Shell plc – a single company under a single chief executive, with a British corporate structure and its legal seat in Britain, but with its headquarters and tax residence in the Netherlands.

In 2005 Shell became a single company with a British corporate structure, but with its headquarters and tax residence in the Netherlands

It will be interesting to see how, in its second century, Royal Dutch Shell will manage to deal with the ever more turbulent markets of the world, with oil prices now at an all-time high and the emergence of the new economic giants of Russia, China and India. The importance of Shell as a world player is underlined anecdotally by the joke that when the Chinese president last visited the Netherlands, it was on his way to talk business at Shell headquarters that he stopped off at the royal palace in The Hague for a cup of tea with Queen Beatrix.

What links the various volumes together is their common focus on five key aspects of Shell as a business enterprise. With a great wealth of data the authors analyse, first, the worldwide spread of Shell’s activities, and the changes these have undergone over time through diversification, regional partnerships and strategic realignments. Secondly, the authors examine Shell’s attempt to shape and reshape its internal organisation, which, in response to worldwide business and cultural developments, has now become far more multicultural and international in outlook and composition than it used to be. Thirdly, they consistently focus on the issue of how Shell has managed for so long and with such great success to remain competitive in the face of so many different challenges. Fourthly, they have a fascinating story to tell of how, from the 1970s onwards, Shell has used technology and innovation to create growth and to develop new ways of being competitive. And finally, they analyse the interplay between Shell as a business enterprise on the one hand and on the other the world of politics, where both sides are increasingly, but in very different ways, having to deal with the challenge of finite and increasingly scarce energy resources.

On this last point, however, I feel that the authors stay too much on the side of official politics. What we do not get is a political analysis such as that given, for example, in Anthony Sampson’s riveting The Seven Sisters (1975, 1993), which, though still highly pertinent, is not mentioned in the bibliography. The focus is strictly on the business, and the Kyoto Agreement is not even mentioned in the index. Nor is any attention paid to the long and far-reaching involvement of Royal Dutch Shell with Dutch politics; whereas in actual fact, from Colijn and Gerretson through to former EU Commissioner Frits Bolkestein and now Wouter Bos, the Dutch Minister of Finance, Shell has always managed to attract or supply key players in Dutch politics.

That said, the strength of this new history clearly lies in its thorough, systematic analysis of Royal Dutch Shell from a business perspective, and here the authors have produced a formidable work that bears witness to both the adaptability and the sustainability of this unique Anglo-Dutch multinational. Their work is required reading for anyone who wants to understand the modern world.