New English Edition of Huizinga’s Autumntide Captures His Original Voice Better Than Ever

A century after its first appearance, there is a new and unabridged English translation of Johan Huizinga’s classic Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen

(Autumntide of the Middle Ages). But has the new edition that captures ‘the late medieval spirit’ in France and the Low Countries any added value? Historian Ben Kaplan is convinced it will attract new generations of readers. ‘The translator has captured the poetic qualities of Huizinga’s authorial voice without sacrificing the readability of the text.’

Of all the history books I read as an undergraduate student, none gripped me like Huizinga’s Waning of the Middle Ages, as it was then called. It captured the look and feel of a bygone era with unmatched vividness, firing up my imagination from its first words:

When the world was five centuries younger, all the affairs of life had much sharper outward forms than they do now. Between grief and gladness, between calamity and good fortune, the distance seemed greater than it does to us; everything one experienced had that high degree of immediacy and absoluteness that joy and sorrow still have in the minds of children…. There was less relief from disasters and death than there is now; they were more terrifying and more anguishing. Sickness contrasted more sharply with health; the biting cold and fearful darkness of winter were evils that were much more real. Honour and riches were enjoyed more deeply and more avidly, for they stood out more starkly than they do now against the howling poverty and abasement. A fur tabard, a roaring fire, drink and banter and a soft bed still possessed that intense degree of pleasure…. [quoted from the new edition under review, p. 9]

Historian Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) ranks among the most influential Dutch thinkers of the twentieth century.

Historian Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) ranks among the most influential Dutch thinkers of the twentieth century.Here was a reason to study history: not to learn names and dates, but to penetrate the hearts and minds of people long dead, to see and feel through them a distant world. Decades later, I discovered that, without realising it, I had echoed another lyrical passage from the book in one of my own.

For a century now, Huizinga’s masterpiece has evoked such responses in its readers. Published in twenty-three editions in Huizinga’s original Dutch, translated into at least eighteen other languages, it prompted (along with his other books) the author’s nomination several times for the Nobel prize in literature. Translating such a work poses no easy challenge, and Diane Webb recounts how she first tried to fit the text into ‘a straitjacket of standard, scholarly prose’ before embracing the unconventional features of Huizinga’s style and starting her translation for this new edition over from the beginning. The result is a version of the text that captures Huizinga’s original voice better than either of the two previous English editions. The difference is signalled in the very title of the new edition, where Waning and Autumn have been replaced by Autumntide.

This edition captures Huizinga’s original voice better than either of the two previous English editions

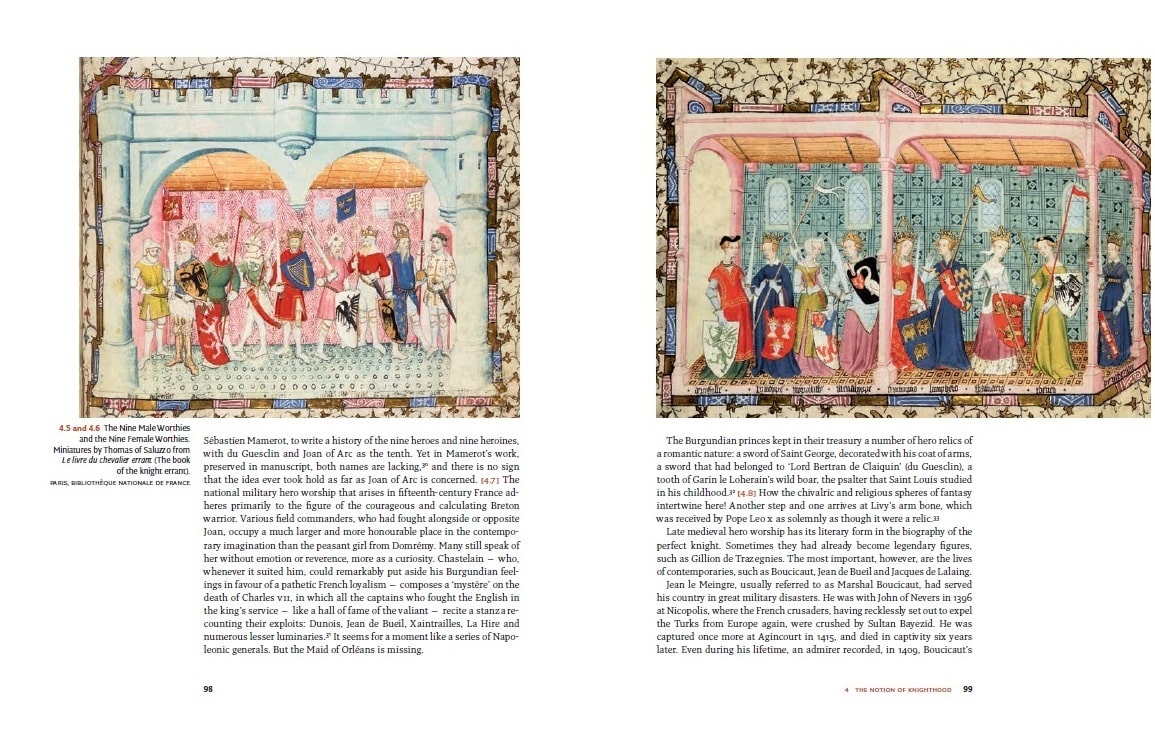

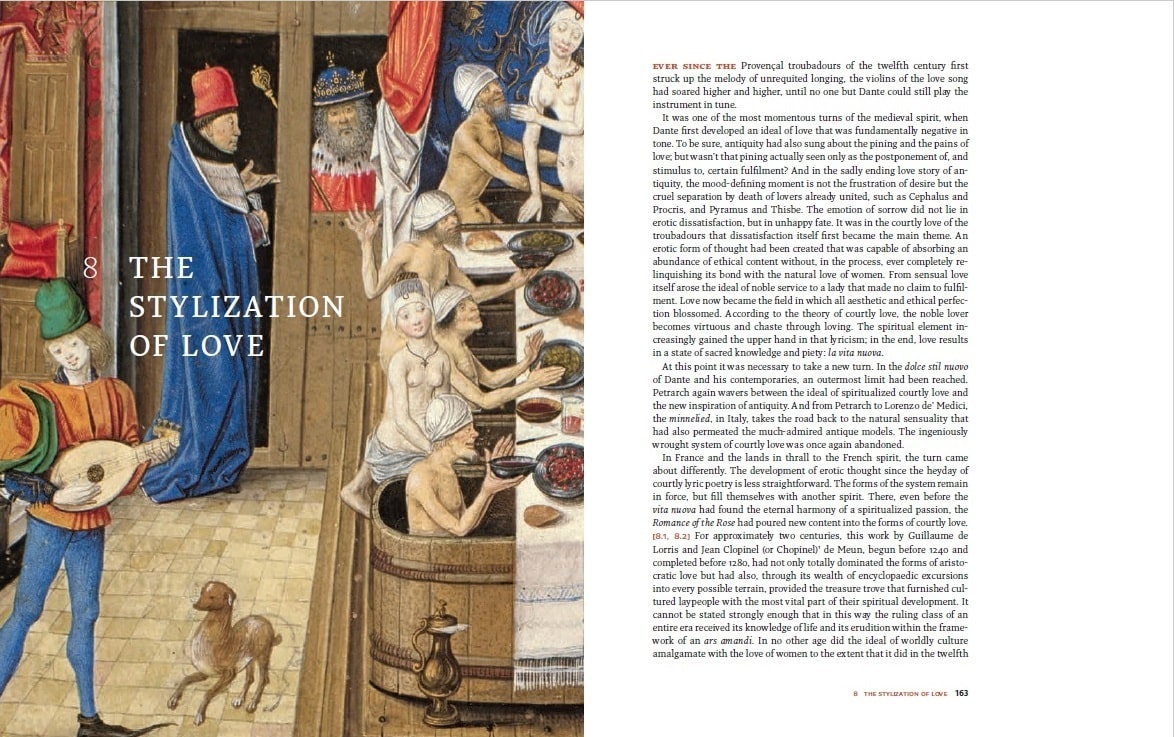

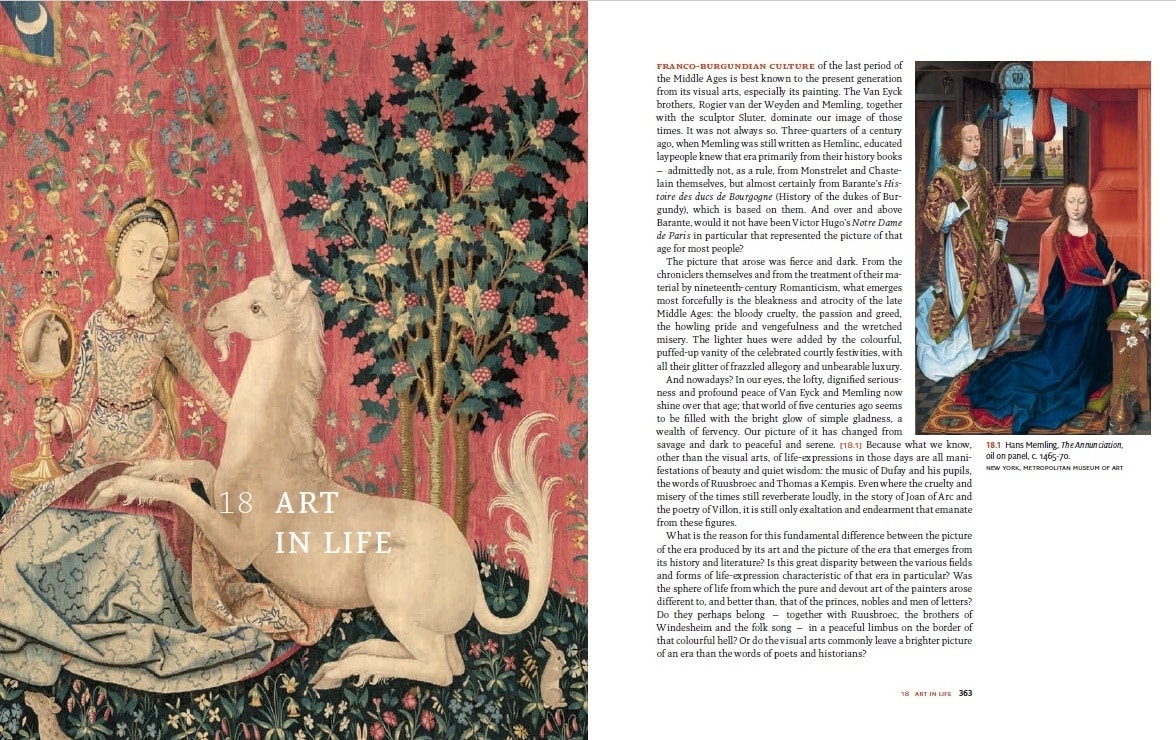

However translated, the title (Herfsttij in the original Dutch) conveys Huizinga’s conception of the period he treats as one of ‘final flowering’ (p. 306) – a period that sees a medieval culture stretching back a thousand years reach its culmination and at the same time its exhaustion. The essential content remained the same: in the secular realm, for example, Huizinga identifies chivalry as continuing to provide the dominant ethos, not just among princes and nobles but also (a questionable claim) among urban commoners. What has changed is the tendency for symbols and forms now to ‘overrun’ substance and content: ceremony and etiquette are so elaborated as to be, in modern eyes, laughable; the expression of sentiments becomes mechanical and superficial; details are specified exhaustively; exaggeration, excess, and ostentation run unchecked; everything spiritual or abstract is reduced to mundane, corporeal form and so made visible. In this last process in particular Huizinga found the key to understanding the character of the period. ‘The fundamental trait of the late medieval spirit’, he asserts, ‘is its inordinately visual character. This is closely related to the atrophy of thought. Thinking is done visually…’ (p. 426).

Huizinga’s subject is nothing less than ‘the late medieval spirit’

It was in fact the visual arts that first drew Huizinga to his subject – the art, specifically, of the Burgundian lands, which stretched in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries from Burgundy and Franche-Comté in the south to the Low Countries in the north, though not as far as Huizinga’s native Groningen. The paintings of Jan van Eyck in particular, some of which were shown in a 1907 exhibition in Bruges, inspired Huizinga. Once he began reading extensively in the textual sources from the period, though, he found it impossible to consider Burgundian culture separately from French, and in the end he did not confine his book strictly even to the French and Burgundian realms.

Huizinga’s subject is nothing less than ‘the late medieval spirit’, which he also refers to as ‘the late medieval mode of thought’ and ‘the fifteenth-century mind’ (at one point he uses the German term Zeitgeist). This he conceives as a unitary thing, a common mindset shared across large if unspecified parts of Europe and by people of all social ranks. Modern historians find this conception problematic for the way it elides cultural differences, and above all for the diffusionist theory that informs it, in which the culture of non-elites is entirely derivative, trickling down especially from courtly circles.

Huizinga was not the kind of historian who traces the origins of the modern in the past. To the contrary, he represents the past as a foreign country with a profoundly alien culture, one that can best be understood not by tracing its origins or legacies but as a coherent, self-contained system with its own logic. In this respect, Autumntide shows the influence on Huizinga of the discipline of anthropology, an influence even more explicit in his pioneering work on forms of play, Homo Ludens. One of the most common adjectives in Autumntide is ‘primitive’, used as a descriptor for many aspects of late medieval culture. Heraldic figures are compared to totems; the practice of naming artillery canons is characterized as a trait of ‘primitive anthropomorphism’ (p. 333).

Huizinga’s use of anthropology had few imitators for many decades, nor did later historians adopt the practice from him, but this aspect of his work anticipated the ‘new cultural history’ that emerged in the 1980s and continues to be practised by many historians. The latter would distance themselves, though, from the pejorative connotations of the word ‘primitive’ and, even more, from Huizinga’s conception of medieval people as childlike, a trait he discerns in their emotionality, their impulsivity, and the ‘immediacy and absoluteness’ (p. 9) of how they experienced life. ‘Between hellish oppressions and the most childish amusements, between horrible hard-heartedness and tearful tenderness, the populace staggers like a giant with a child’s head’ (p. 36). Such characterizations may be tendentious, but it is difficult not to find them captivating.

The new English edition features over three hundred paintings and prints, illuminated manuscripts, and miniatures pertinent to Huizinga’s discourse.

The new English edition features over three hundred paintings and prints, illuminated manuscripts, and miniatures pertinent to Huizinga’s discourse.This new edition of the book, produced to mark the centenary of its publication, is special in several respects. Based on the fifth and final Dutch edition that Huizinga himself worked on, it presents the work unabridged, so a reader can savour the entire text. I have already remarked on how well the translator has captured the literary, indeed poetic qualities of Huizinga’s authorial voice. This she manages to do without sacrificing the readability of the text. The edition is gorgeous – solidly bound with thick paper, and with high-quality illustrations of most, if not all, the works of art Huizinga mentions in his text, plus others. At the same time, the edition has been produced to a high scholarly standard. It includes all of Huizinga’s original prefaces, notes, timeline, and a reconstructed bibliography of works cited by the author. Huizinga’s extensive quotations from primary sources are given both in their original language and in English translation. In addition, historian Graeme Small (Durham University) has provided in the form of an epilogue an insightful essay discussing Huizinga thought, the genesis of Herfsttij, and its afterlife down to today.

Autumntide of the Middle Ages, the masterpiece of the most famous historian the Netherlands ever produced, transcends its subject matter; it is one of the classics of modern Dutch writing. This new edition is sure to enhance its appreciation by new generations of readers.

Johan Huizinga, Autumntide of the Middle Ages: A study of forms of life and thought of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in France and the Low Countries. Translated by Diane Webb. Edited by Graeme Small and Anton van der Lem. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2020, 616 pages