New Holocaust Museum Shows The Persecution Of Jews In Its True Colours

Knowledge about the Holocaust and the role played by the Dutch in it is declining – especially among young people. High time, then, for the new National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam. But what can this museum say that has not been said before by dozens of other Dutch museums and memorial sites concerning the history and the persecution of the Jews? Well, for one thing, don’t expect a sober range of dark colours. The museum has opted for a bright décor because, in the end, ‘the persecution of the Jews and their deportation took place in full daylight.’

The location of the National Holocaust Museum, on Plantage Middenlaan, was not chosen randomly: the Hollandsche Schouwburg (Holland Theatre), renamed the Jewish Theatre by the German occupiers, was located on that street. It was one of the most controversial holding places for Jewish men, women and children in 1942 and ‘43. From here, they were transported to Westerbork and Vught, after which they were sent to death camps, far to the east.

The Hollandsche Schouwburg. From here, many Jewish men, women and children were transported to Westerbork and Vught, after which they were sent to death camps.

The Hollandsche Schouwburg. From here, many Jewish men, women and children were transported to Westerbork and Vught, after which they were sent to death camps.© Stefan Müller

Almost half of the more than a hundred thousand Dutch Jews who were killed, mostly in Auschwitz, passed through the theatre. Of all the victims who were removed from the Netherlands through this or other detention centres, only around five thousand returned alive. According to comparative international research, one explanation for this low survival ratio is the ‘efficiency’ of the Dutch civil service and the willingness of many ordinary citizens to turn Jews in.

Diagonally opposite the former theatre, also on Plantage Middenlaan, is another building where the Shoah has left traces: the former Dutch Reformed Church Teacher Training School, adjacent to a daycare centre, has also disappeared. Children up to the age of twelve were housed in the school before they were taken away. Thanks, however, to the courageous resistance of director Henriëtte Pimentel, among others, six hundred babies and toddlers were smuggled to hiding places via the daycare centre next door. They survived.

Crooked legs

The National Holocaust Museum is there, in the neighbourhood that housed the Hollandsche Schouwburg and the former teachers’ school, an area known now as the Jewish Cultural Quarter. “The theatre, which was really just an empty shell since only part of it remains standing, has been a monument since the 1960s,” explains curator Annemiek Gringold. “Survivors, their children and grandchildren regularly come to remember the relatives who were deported from here. The theatre has attracted more and more visitors over the last two decades. You get a feeling of the absence of a community, a feeling we wanted to preserve in our plans. The theatre is part of the Holocaust Museum, but above all it remains a place for reflection and remembrance.”

Curator Annemiek Gringold: ‘Many museums about the Holocaust work as an experience with dark colours and the reconstruction of situations. We are not building on that.'

Curator Annemiek Gringold: ‘Many museums about the Holocaust work as an experience with dark colours and the reconstruction of situations. We are not building on that.'© Anneke Hymmen

“To commemorate the victims of the Shoah, you must first know what happened to them,” Gringold explains, which is why an introductory film is shown in the theatre. There are also fixtures in the form of glass drops in which audio fragments of farewell letters, emergency telegrams and diaries are presented. In addition, a model of the theatre as it looked at the time has been reconstructed and, in the garden behind the former stage tower, a visual work of art invites visitors to reflect on all that occurred here.

In the former daycare centre, “we explain in a dignified and modest way how the persecution of the Jews happened,” says Gringold. “Dignified and modest, because we do not want to focus on what the Nazis made of it but, rather, on their victims: toddlers, children, teenagers, men, women and the elderly. Also, while many museums about the Holocaust work to reconstruct situations and create an experience of dark colours, we did not choose to go that way. Our museum opts for a clear presentation in which we tell visitors to their faces how Nazis and Dutch officials collaborated in the persecution. Some walls are, therefore, papered with measures such as those regarding the Aryan Declaration, the fishing bans or the mandatory wearing of the yellow star.”

Dress of Betty Appelboom, with a Star of David on the chest, on display in the National Holocaust Museum.

Dress of Betty Appelboom, with a Star of David on the chest, on display in the National Holocaust Museum.© Jewish Museum

In a series of wooden installations, all in different shapes and types of wood, Gringold and her team have also included objects that refer to the victims. Some structures have crooked legs – a reference to the vulnerability of humans. Of the two thousand objects in the Holocaust Museum, nineteen are highlighted as ‘forget-me-nots’ – “things that we believe every visitor should see”. Separate rooms will house temporary exhibitions, lectures and school activities.

Avoiding the kitsch

What is certain is that the creation of the National Holocaust Museum has been carefully considered. For example, there were concerns about what such a museum could provide that Amsterdam did not already have. There are many sites commemorating Amsterdam’s Jewish history, such as the Portuguese Synagogue, the Resistance Museum, the Jewish Museum and the Anne Frank House.

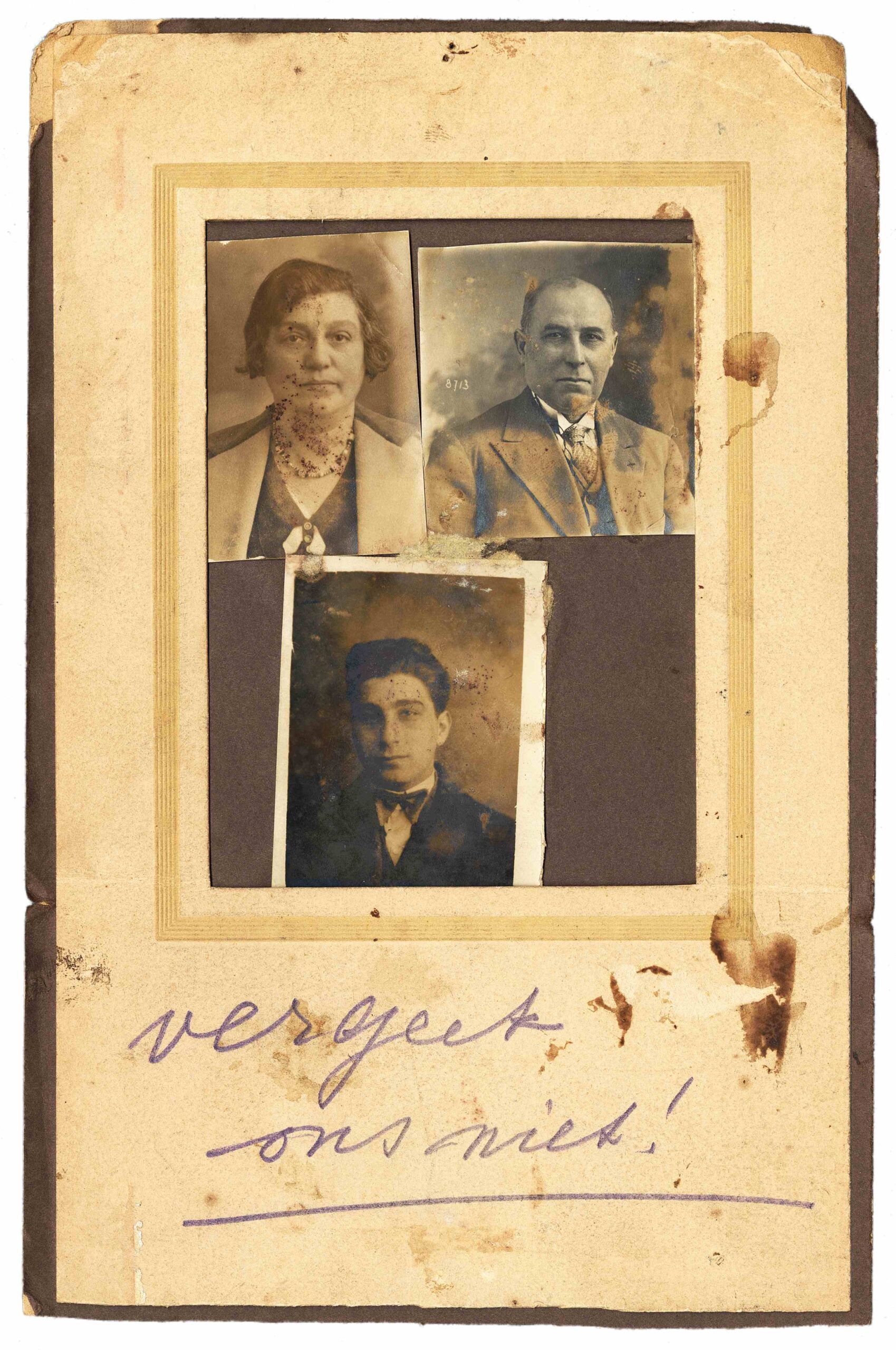

Cardboard frame with passport photos of an anonymous family, text ‘don’t forget us!’ written in pencil, on display in the National Holocaust Museum.

Cardboard frame with passport photos of an anonymous family, text ‘don’t forget us!’ written in pencil, on display in the National Holocaust Museum.© Jewish Museum

A similar argument also arose in the run-up to the construction of the Holocaust Names Monument, on which the first and last names of 102,000 Jewish, Sinti and Roma victims can be read. The objections were varied: one location, the Wertheim Park, met resistance from residents who feared losing their tennis court, others suggested that after Ground Zero in New York and the Jewish Museum in Berlin, ‘starchitect’ Daniel Libeskind had already built enough memorials. Some thought his design was too large, while others felt walls full of names was an outdated concept.

The well-known sociologist and professor emeritus Abram de Swaan (UvA) also had little sympathy for a names monument at the time. De Swaan feared a “flashy and noisy monstrum” and compiled a book of objections entitled Bedenkt Eer Gij Gedenkt (Think before You Remember). When the monument was completed in 2021, however, De Swaan changed his mind and admitted that he had made a mistake.

And how does he view the National Holocaust Museum now, two years later? “It’s a very good idea,” says the academic firmly. “The conversion of a historic site is always sensitive, and it is true that we already have a lot – you can spend a full day walking past Jewish monuments in the Jewish Cultural Quarter – but a museum about the Holocaust, where it was documented for the first time and visualized? No, that wasn’t there yet.”

Sociologist Abram de Swaan: 'A museum where the Holocaust was documented for the first time and visualized didn't exist yet.'

Annemiek Gringold agrees that anyone looking for traces of Jewish life in Amsterdam will easily find what they are looking for, but also stresses the different context of each place. “For example, the synagogue and the Jewish Museum highlight traditional Jewish life, the Resistance Museum is about the individual’s options for action and the Anne Frank House tells the history of the eight residents of the Secret Annex. The camps at Amersfoort, Westerbork and Vught take a closely related approach. In other words, there is a lot out there, especially within the context of the Second World War, but the narrative in the Netherlands remains fragmented. If we only see events in fragments, our knowledge of them will remain stagnant. The National Holocaust Museum presents a compact but integral story about the period before, during and after the Shoah, with due attention also to the perspective of the non-Jewish society.”

Holocaust survivors receive a tour of the new museum.

Holocaust survivors receive a tour of the new museum.© Raymond van Mil

A reality of colour

Non-intrusive, clear and transparent, that is how Gringold wants her museum to be. For its construction, the museum turned to Office Winhov, the architectural firm that specialises in the reuse of existing buildings and monuments.

Architect Uri Gilad, who himself lost family members in the Holocaust, explains: “We did not want to put an ego sticker on it. This should not become yet another landmark. Our only objective was to house and make visible an important and tragic piece of the past. Actually, our architecture is fairly secondary – not in the sense of being submissive, but of being as close as possible to the story.”

The entrance to the National Holocaust Museum on Plantage Middenlaan in Amsterdam.

The entrance to the National Holocaust Museum on Plantage Middenlaan in Amsterdam.© Stefan Müller Photography

Gilad’s colleague Inez Tan elaborates: “In our design we chose to keep the late nineteenth-century facade of the Nursery School intact so that visitors can see that this used to be a school, a place where many children came. That is why we kept the typical school tiling inside the building.” Office Winhov also felt it was important to include the tradition of Jewish architects in the neighbourhood in the new design – in the case of the nursery school, that meant Abraham Salm (1857-1915).

Next to the facade, Tan and Gilad have built an entrance surmounted by fine-meshed masonry that offers a view to the other side of the street and the Hollandsche Schouwburg. They chose light bricks because they believed it was important not to work with dark tones. “In eighty percent of the Holocaust museums, the predominant colours are anthracite or black. However, the persecution and deportation of Jews happened in full daylight, under the sun, in a reality of colour. We wanted to do justice to that idea in the museum.”

Increased extremism

Compiling a fragmentary account, adding what has not yet been told: that is what the National Holocaust Museum has set out to do. But the museum also focuses on educational tasks. Education is desperately needed: the recent Netherlands Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Survey (Claims Conference, New York, 2023) showed that fifty-three percent of respondents did not consider the Netherlands as a country that helped bring about the Holocaust. That figure rises to sixty percent in the case of millennials or Gen Z youngsters.

Twelve percent think the Holocaust is a myth or is being magnified, a proportion that swells to a quarter among those in their forties, many of whom cannot even name an extermination camp. Few countries studied are doing worse than the Netherlands, according to the survey. More worrying is that it seems as if ignorance and anti-Semitism are increasing in line with an increase in commemoration and information initiatives.

“Around the time when 9/11 also took place, we started to notice a rise in extremism, with Islamism on the one hand and the extreme right on the other,” explains historian Christophe Busch, former general manager of the Kazerne Dossin in Mechelen and current director of the Hannah Arendt Institute, also located in that city. “In response to this new extremism, a memory tree has also emerged, intended to recall the past and translate lessons about collective violence in the past to today, with attention given to victims, perpetrators and bystanders.”

Christophe Busch (Hannah Arendt Foundation): ‘As a museum you must demonstrate that there is potential evil in every person.’

Busch, who obtained his PhD from the University of Amsterdam with a thesis on the Holocaust, believes that museums such as the one on Plantage Middenlaan have an extremely important educational mission. “But that remains difficult, because you have to lift the story beyond the symbolic simplification,” he says. “Take the camps: refugee camps are very different from internment camps, which in turn are different from concentration or extermination camps. Camps are dynamic spaces and cannot be simplified.

The transition from a state of exception to one of normalisation is also dynamic, and I’m not even talking about the effect of group dynamics and polarisation. A museum must demonstrate that there is potential evil in every person, and that any number of factors and contexts can unleash and activate that evil. In that respect, moral dilemma training is also very important. If we say, ‘the Nazis are the worst people who ever existed’, we allow visitors to keep a safe distance and they don’t learn much from a museum visit.”

But museums must also take into account the realities of the lives of young people today. Those with a recent migrant experience are, in particular, much less concerned with the Holocaust than with the situation in the Middle East. “A possible translation here could concern trauma,” Busch suggests. “Every family has its own coping strategies, from shame to guilt to silence and bearing witness and so on. We know from epigenetics that trauma can even be passed on from generation to generation. This not only happens in families affected by the Holocaust, but in any family with a difficult migration background.”

Our own victims first?

An additional challenge for Holocaust museums, and therefore also for the new museum in Amsterdam, is the ‘competition’ between victims. As Abram De Swaen attests, “there is indeed sometimes a question of ‘who has suffered the most’. It is therefore crucial that museums look for the common denominator. Large groups in society still have to fight for attention and recognition, whether their focus is slavery, racism or sexual orientation. Although things are changing: look at how the movement against Zwarte Piet was fought in recent years. That was brilliant! It is also good that the Netherlands will soon (in 2028, LD) have a National Slavery Museum.”

De Swaan does not fear that the museum on Plantage Middenlaan will fall into the trap of ‘our own victimhood first’. “On the contrary, it will fit nicely into the Jewish Cultural Quarter, and when I look at that neighbourhood as a whole, I don’t see any vulgarity or sensationalism. As for the issue that many people do not know what the Holocaust is about, especially young people. Well, ignorance may be partly a trait of youth. Young people who can put the Holocaust into perspective might also believe the world is flat, or simply not care about all that knowledge. Provocative statements and stubborn denial are all multiplied by negative feelings about the situation in the Middle East. We must dare to see some reactions in context.”

Meanwhile, Annemiek Gringold is the last to underestimate the weight of her task. “Emotions, prejudices and lack of knowledge: it is a difficult mix. That is why we have opted for a museum presentation in which the educational programs will make it easy to move towards the importance of democracy and the rule of law, media literacy and exclusion mechanisms. In the museum, we will also have neutral spaces that are separate from the exhibition and offer a safe conversation environment. But a magic wand to tackle all challenges? Unfortunately, that is something that the National Holocaust Museum doesn’t have.”