It has been a rewarding edition of TEFAF Maastricht for a lot of Dutch museums. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Teylers Museum, Bonnefantenmuseum and Rembrandthuis all acquired new artwork at the world’s leading fine art and antiques fair.

Rijksmuseum Twenthe

The Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede was able to purchase one of TEFAF’s showpieces. Not a painting, but a doll house. And it’s a unique specimen.

The doll house contains one hundred silver miniatures and belonged to Anna Maria Trip (1712-1778). She was a Groningen descendant of a well-known Amsterdam regent family.

Anna Maria Trip’s doll house is one of only ten remaining Dutch miniature houses from the seventeenth or eighteenth century. It was the only house still in the possession of descendants of the original owner. Until this year’s TEFAF, where the Haarlem silver specialist John Endlich Antiquaries exhibited it on behalf of the family.

Rembrandthuis

The Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam acquired an etch by Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680). The museum has purchased The Holy Family in a living room dating from 1643.

Ferdinand Bol was one of the most successful Dutch Golden Age artists trained by Rembrandt between 1636 and 1640. He was the only pupil of the famous painter who made a large number of etchings as well as paintings.

The etching can be seen from 7 June in the summer exhibition Inspired by Rembrandt, which shows how the Dutch master has been a great source of inspiration for many artists for centuries.

Bonnefantenmuseum

The Bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht acquired a portrait by Michiel van Mierevelt (1566-1641) at TEFAF. The portrait shows Frédéric Maurice de La Tour d’Auvergne a few years before he was appointed Governor of Maastricht in the United Provinces in 1629.

The museum states: “Michiel Jansz.van Mierevelt painted the portrait of young Frédéric Maurice de La Tour d’Auvergne, duc de Bouillon, prince of Sedan in 1626, arguably when the artist was at the apogee of his artistic powers as official court portraitist in the Stadtholder court of Prince Maurice of Orange-Nassau, in The Hague. He portrays the young duc de Bouillon, an ambitious close relation of the Orange-Nassau dynasty, at the age of twenty-one, dressed in armor, an allusion to his military ambitions.

Frédéric Maurice, named after his powerful uncles, Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, and Prince Maurice of Orange-Nassau, had received his early military training in Holland, under his uncles’ guidance. Here, Mierevelt depicts a primed, motivated young man, on the verge of a sharp elevation from an already illustrious standing. Only six years after this portrait was painted, aged only twenty-seven, he was made the Governor of Maastricht and the United Provinces.”

Teylers Museum

Haarlem’s Teylers Museum bought the painting Veiled woman by Dutch artist Matthijs Maris (1839-1917). Matthijs Maris, the middle of three brothers from The Hague, initially made work in the style of the Hague School, but later in his career he experimented with innovative painting techniques. The veiled woman is a textbook example of this later period. The museum already has some drawings and etchings of this progressive artist.

The museum also purchased two drawings at TEFAF: a miniature on parchment, Black foot polecat, by French artist Nicolas Robert (1614-1685) and a drawing called The twelve-year-old Christ in the Temple. The latter work was created by ‘the Master of 1527’, a Leiden artist whose name remains unknown.

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam went on a TEFAF shopping spree. It was able to obtain two sixteenth-century panels, painted around 1555 by the Haarlem artist Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574). One panel depicts Pluto and Cerberus and the other shows Samson grasping the gates of Gaza.

Both panels were originally part of a group of twelve known as The Twelve Strong Men. This group comprised four iconographic sets of three panels: one of a Greek god, one of Samson and one of Hercules. Each of these four ensembles is devoted to a particular theme: triumph over death, sinfulness, faith, and evil.

The panels are examples of the Brunaille style of painting, executed exclusively in shades of brown. With great virtuosity Maarten van Heemskerck’s counters the limitations of the format’s modest dimensions, and the muscled bodies seem to burst from their cramped frame.

The group of panels was broken up in 1946 when it was auctioned on the open art market. Four of them were already in the Rijksmuseum collection.

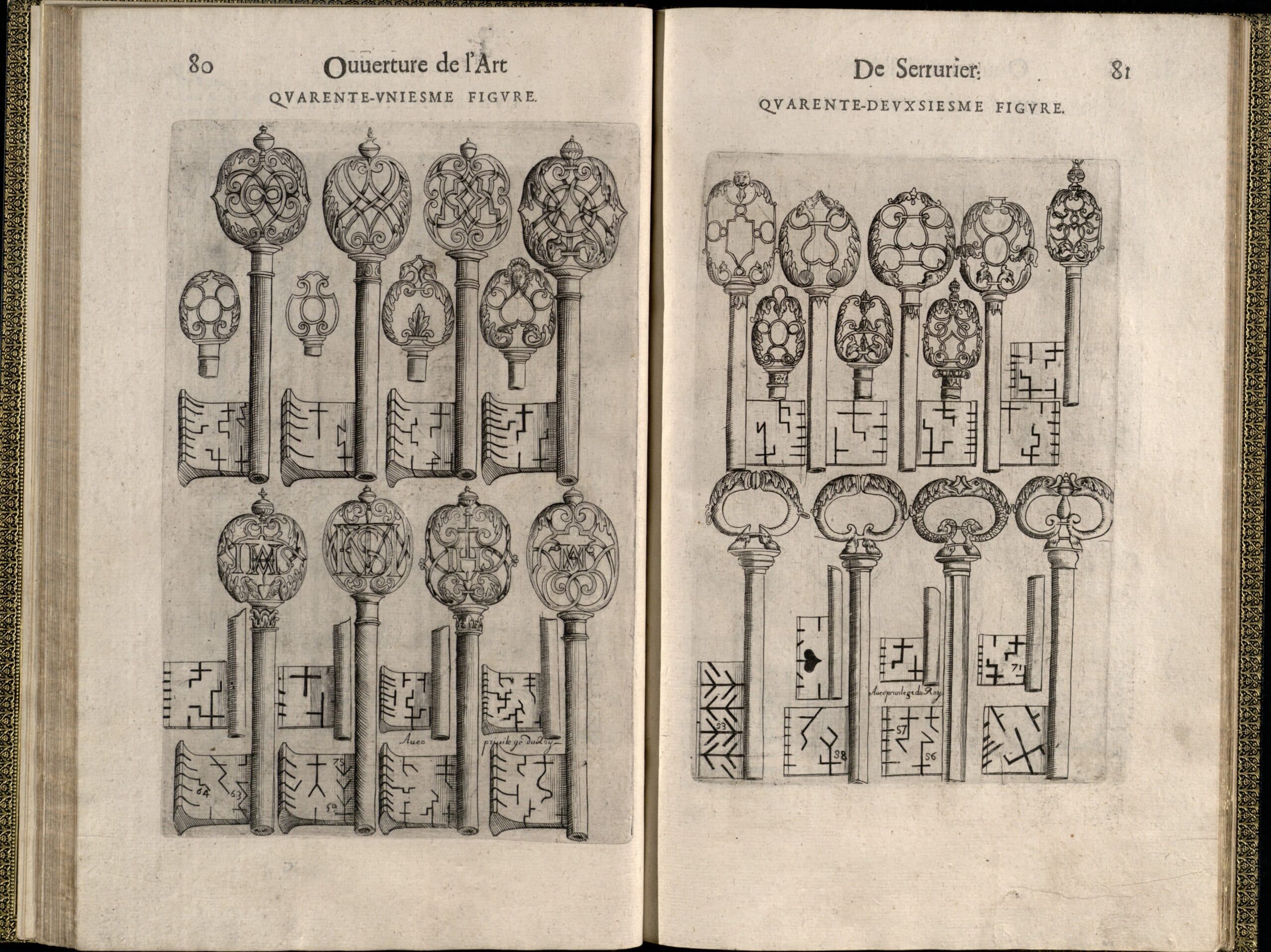

The Rijksmuseum also acquired a French book dating from 1627: La fidelle ouverture de l’art de serrurier.

The book is the earliest printed work dedicated to the art of making special locks and keys. Its author was the French master locksmith and architecture theoretician Mathurin Jousse (1575-1645), who was born in La Flèche, in the Pays de la Loire region of France. The making of locks and keys was a secret craft that was passed on in the blacksmith’s forge.

This book containing descriptions of methods of manufacture will complement the Rijksmuseum’s collection of locks and keys exhibited in the Special Collections Gallery. It will also be an important addition to the vast collection of handbooks for artists held by the Rijksmuseum Library.

The 65 illustrations (copper engravings and wood prints) depict not only richly decorated keys and lock mechanisms, but also the first wheelchair and even prosthetic hands and legs. Technical manuals such as this would often either be worn out through use or go out of fashion with the advent of new inventions, and they are exceedingly rare nowadays.

The third work that is obtained by Rijksmuseum is a painting by Joseph-François Ducq (1763-1829), ), an artist from the Southern Netherlands (Flanders). His portrait from 1813 shows engraver Joseph-Charles, also called Jozef Karel, de Meulemeester working in the Raphael Loggia in the Vatican in Rome.

De Meulemeester had set himself the aim of reproducing Raphael’s entire oeuvre, and he can be seen here working on a drawing of a section of the ceiling above him

The Rijksmuseum actually owns an engraving created by de Meulemeester, showing Raphael’s Saint Cecilia.

De Meulemeester and Ducq belonged to a group of artists from the Southern Netherlands whom the government had sent to Rome to complete their education and to study the Italian masterpieces. This fine depiction of the activities of an artist in Italy is also a historical document, because on the shadowed pillar on the left we can see, written in red and brown paint, the names of all the artists who had come from the Southern Netherlands to Rome, with their year of arrival.

The Amsterdam Rijksmuseum owns works by Northern-Netherlands artists who were also sent to Rome. Both groups of artists mingled. However, the museum does not own many works by members of the Southern-Netherlands group. It will exhibit this portrait in the museum’s Waterloo Gallery, which is partly dedicated to Dutch artists in Italy.