Nothing Stands Between the Viewer and Art in Food Art Museum LAM

Hidden in the nineteenth-century park behind the world’s most famous tulip garden Keukenhof is the only food art museum in the Netherlands. The LAM takes a critical look at consumption but avoids approaching it with moralism and art historical jargon.

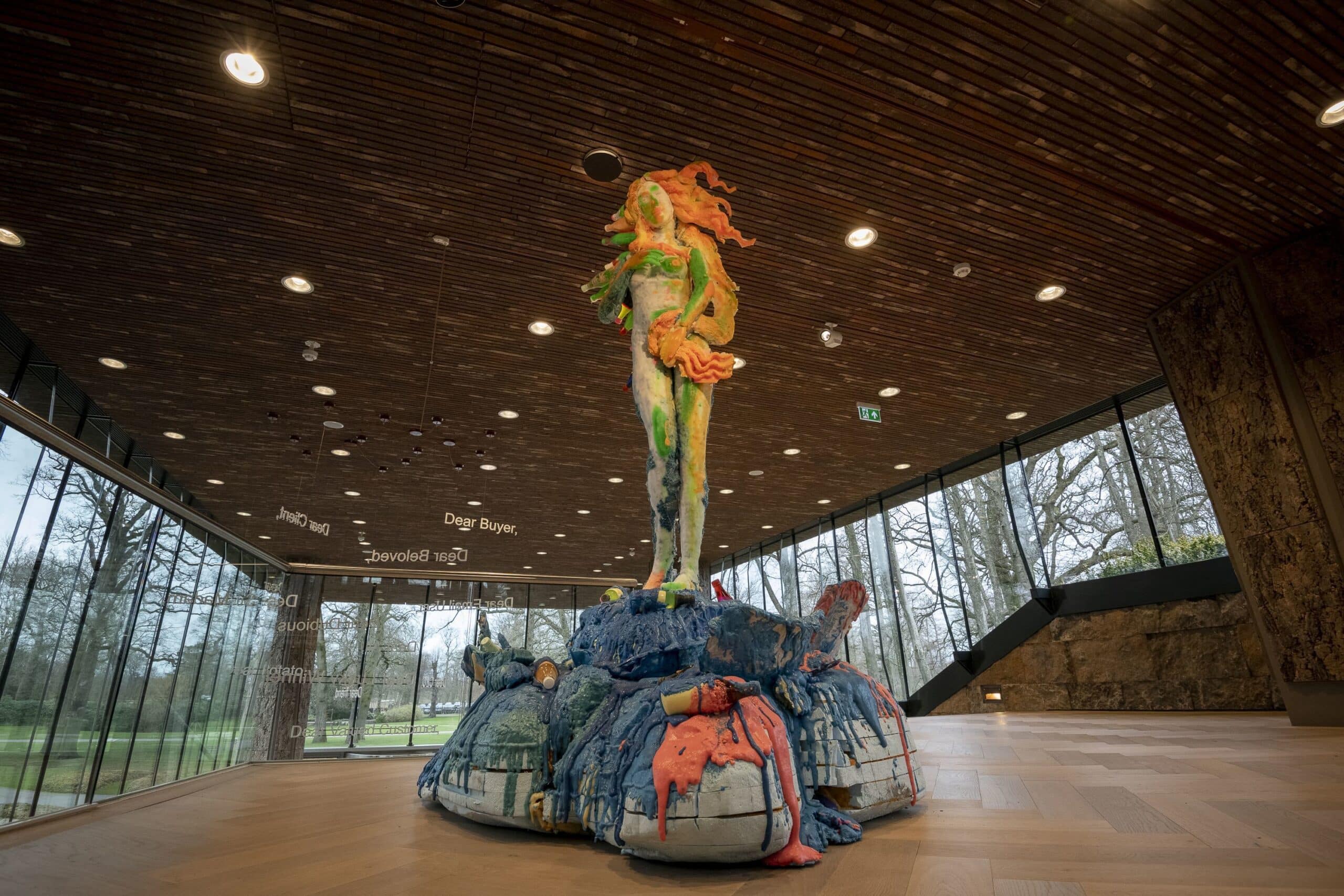

The Birth of Venus is reborn. Not in the Uffizi gallery where the original that Sandro Botticelli painted around 1483 hangs, but in the North Holland Flower Bulb Region. Sculptor Folkert de Jong recently made a contemporary version for the LAM and anyone who knows the original immediately recognizes the fluttering, long hair, the neatly folded right arm and the left hand in front of the genitalia. Yet the differences are greater than the similarities. The hair of the new Venus is virulent orange, and her skin has turned green and blue in places. She does not stand on a giant shell in the surf but rises from the plastic soup that is currently suffocating the ocean.

Folkert de Jong, Dea Consumptia

Folkert de Jong, Dea Consumptia© Corine Zijerveld

With his piece of sculpture, De Jong criticizes Botticelli’s masterpiece, which he considers a prototypical pin-up. But even more than the degradation of women to objects of lust, this work is about the harmful consequences of our consumerism. The sculpture is made up of epoxy, polyurethane foam, and Styrofoam – materials from the chemical industry that are widely used in construction and are extremely harmful to the environment. The apt name for De Jong’s Venus is therefore Dea Consumptia.

LAM’s latest acquisition fits well alongside Itamar Gilboa’s Food Waste Project. This Israeli artist kept a food diary for a year in which he noted how many loaves of bread, bottles of olive oil, bulbs of garlic and whatnot he had consumed. He reproduced every used item from the shopping list in plaster. The resulting installation with more than eight thousand objects is impressive but also somewhat disturbing. 111 litres of red wine? 123 litres of diet coke? And a single person’s thirst produces such a load of packaging material?

Itamar Gilboa, Food Chain Project

Itamar Gilboa, Food Chain Project©Bibi Vet

That Gilboa’s work counts as ‘the Night Watch of the LAM’ is telling. Visual imagination and a critical undertone are the two strands of LAM’s museum DNA. And that is quite remarkable when you consider that the institution was initiated and is financed with capital from the business community.

The first seed for this remarkable museum was planted in 2008 when Jan van den Broek, the eldest son of supermarket founder Dirk van den Broek, started a foundation with which he wanted to stimulate art and culture among young people. The VandenBroek Foundation joined the talent programme of the Concertgebouworkest, (Concertgebouw Orchestra) the Teekenschool (Drawing School) of the Rijksmuseum and the Nationaal Muziekinstrumenten Fonds (National Musical Instruments Fund). In addition, the foundation wanted to construct its own building with exhibition space. The choice for a location fell on the Keukenhof estate in Lisse, where the VandenBroek Foundation had already sponsored the restoration of the old castle and had plans for a cultural country estate.

Kathleen Ryan, Bad Grapes

Kathleen Ryan, Bad Grapes© Corine Zijerveld

Most private museums have their origins in the collecting passion of an individual who wants to share his treasure with a wider audience – Voorlinden in Wassenaar and Museum MORE are good examples of this. But the LAM has gone the other way. First, there was the idea to build a museum and only then did the collection of art start. In less than ten years, a collection of more than four hundred works has been brought together. The chosen focus is close to the world of the entrepreneurial family: food and consumption. That can very literally be a painting of an apple, but more often the choice has been made for work that is more layered as well as more critical.

In 2015, the construction of the museum began, a stone’s throw from the place where every spring a million tourists come to marvel at what is probably the most famous flower garden in the world. Compared to the Keukenhof, the LAM is an oasis of peace. With its contemporary appearance, the museum building contrasts sharply with the classicist castle from which the flower bulb parade takes its name, but it does not clash with its surroundings. It looks very modest and a lot smaller than it really is.

LAM

LAM© Corine Zijerveld

This is due to the narrow façade and the way in which the building is half sunk into one of the five embankments on the edge of the estate. On the lower floors, the use of natural bluestone enhances the underground impression. The top one and a half floors are built of hand-baked bricks in which clay is mixed to allow the building to blend into the surrounding vegetation. The landscaping is also in line with the design of the nineteenth-century Zocher gardens, with strawberry plants and blackberry bushes here and there as a nod to the art inside.

LAM

LAM© Ronald Tilleman

Long before it became commonplace during the corona pandemic, you could only visit the LAM with a ticket purchased online for a specific period. With this small barrier, the museum hopes to attract people who are genuinely interested and have actively chosen to come here instead of ‘impulse visitors’. It is also a means to spread the public and never have more than a few dozen visitors in the house at a time. This way you do not block each other’s view, which is more likely in the LAM than elsewhere. Contrary to the general trend to hang fewer and fewer works in the gallery, the rooms here are relatively full. What is also different than usual: text boards with explanations of themes or even titles are nowhere to be seen. Nothing here stands in the way of direct contact between the viewer and art.

© Ronald Tilleman

The LAM therefore explicitly focuses on audiences who are not normally inclined to visit a museum and quickly feel ‘too dumb’ during a rare cultural outing because all art historical information is over their head. In the LAM, almost everyone finds something that appeals to him or her. The museum collection includes photorealistic paintings but also sculptures, video works and large-scale installations. No medium is missing. More attention has been paid to collecting a wide range of works rather than in depth, quite a few artists are represented with one work. The pieces are international. Work by up-and-coming talent hangs and stands alongside that of arrived greats such as Yinka Shonibare, David Jablonowski and the Chapman brothers.

Upon entering, the visitor can activate the Wi-Fi and open a website that is only accessible in the museum. Guided tours are offered along five works randomly selected by the computer. Information comes in the form of a video or news item, a fact or associative text. Incentives to look, without a moralistic message. The classical art historical information is only evident at a deeper layer, certainly not at the beginning. In addition to these routes, viewing tips are also offered, playful tools to focus our visual attention such as ‘count all the lemons in the museum’ and Viewing Coaches give tailor-made tips at every museum room.

© Corine Zijerveld

The public is actively involved where possible. For example, you could make your favourite meal known for Christmas 2021 on a website that artist Tom Heerschop then used to compile a collective culinary portrait of the Netherlands. It was a big hit, just like the Viewphone in quarantine time. On Friday afternoon, curators and tour guides were ready for a one-on-one conversation about art, which even people phoning in from Egypt and further afield enjoyed immensely.

© Bibi Veth

But a standard visit also has a lot to offer and easily exceeds the three quarters of an hour that the museum itself sees as optimal. The walk through the open, interlocking halls follows a cadence in which the subtle is alternated with the extrovert. The last room looks like a shop with luxury items. A nod to retail, of course, but it’s also a candy store full of guilty pleasures. However, the museum shop and the restaurant that you expect afterwards are missing. As is in keeping with a museum with a critical eye on consumption.