The Obscured Story of Aspasia and Other Enslaved People in Dutch Archives

For a long time, the study of the history of Dutch slavery has been dominated by the perspective of the coloniser. Slave traders and plantation owners compiled the sources that are presently available, while the experiences of enslaved people themselves have rarely been preserved. But more and more researchers are trying to give those enslaved people a voice. Traces of their voices are ubiquitous in archives, albeit difficult to find and in fragmented form. Thanks to new techniques, more and more of these obscured stories are emerging, writes Jessica den Oudsten.

Two creditors were mentioned in the estate inventory of plantation owner Jan Pieter Pfeffer, which was drawn up after his death in Amsterdam in 1755: the wealthy plantation owner Salomon du Plessis (1705-1785), to whom Pfeffer owed nearly 1440 guilders, and a woman named Aspasia whom he had enslaved. She demanded two guilders from him. Aspasia said that “two guilders of hers remained in the custody of the deceased”, an amount that after Pfeffer’s death she now wanted back. Aspasia is also mentioned in Pfeffer’s will, which was drawn up on 12 January 1755. Pfeffer wrote that the enslaved woman Aspasia was to serve him for as long as he lived, but that she would be granted her freedom on the occasion of his death.

Aspasia was aware that this was promised to her in Pfeffer’s will, and she decided to take action. On 8 August 1755, she herself submitted a request for manumission (the release of an enslaved person) to the Court of Police and Criminal Justice in Suriname. This was remarkable because such requests were usually submitted by other parties. In her request for manumission, Aspasia referred to Pfeffer’s will, in which he intended to release her “without acknowledgement of her faithful service.” A copy of the Amsterdam will was also registered in Suriname on 5 July. A week after her official application, on 15 August, the Court approved her request: Aspasia would receive her “release papers”, documents stating that she was free.

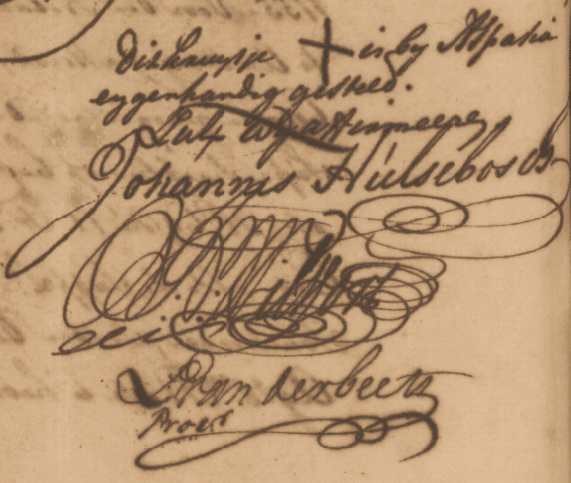

The signature of the enslaved woman Aspasia under her request for manumission (release). It reads: “This cross has been placed in Aspasia’s hand, so we affirm.”

The signature of the enslaved woman Aspasia under her request for manumission (release). It reads: “This cross has been placed in Aspasia’s hand, so we affirm.”source: NL-HaNA, 1.05.10.02, inv. nr. 366, scan 214, 15 August 1755

The perspective of the coloniser

The documents in which the life’s estate of Jan Pieter Pfeffer was settled primarily show the perspective of the coloniser: Pfeffer was the owner of the coffee plantation Onvernoegd on the Perica river in Suriname and held shares in ships, assets which needed to be distributed after his death. Yet from the same sources also emerges the story of Aspasia. By delving deeper into different archives and combining multiple sources, I have reconstructed a small aspect of her life together with historian Ramona Negrón. Aspasia took matters into her own hands to get her money and her freedom. Unfortunately, the sources do not mention anything else about her life.

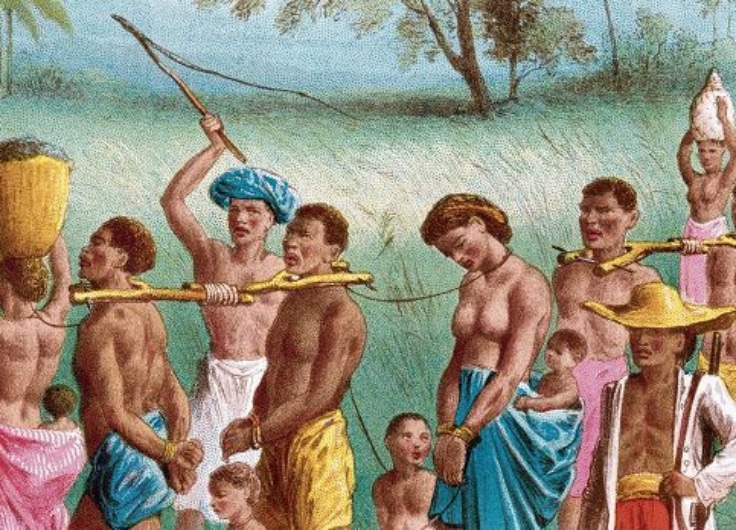

Slave barracks on a plantation, print by the lord Jacob Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, after Gerard Voorduin, circia 1860- 1862

Slave barracks on a plantation, print by the lord Jacob Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, after Gerard Voorduin, circia 1860- 1862© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Considering how many documents in the archives were prepared by or on behalf of slave traders and slave owners, it is often difficult or even impossible to trace the voices of enslaved people themselves. Moreover, enslaved people in most colonies were banned from reading and writing and, if they could read and write at all, had no access to pen and paper. Their testimonials are therefore rare. There do exist valuable personal documents like letters, diaries, or biographies, but these were usually written retrospectively by enslaved people who look back on their lives in slavery later in life. One well-known example is the autobiography by Olaudah Equiano (c. 1945-1797) entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. Equiano published his account in 1789, describing how he was enslaved as a child of eleven and what his life had been like in slavery. Other examples in Dutch can be read in Verhalen van vrijheid: autobiografieën van slaven in transnationaal perspectief, 1789-2013 by Marijke Huisman (Verloren, 2015).

What kinds of sources directly testify to the experiences of enslaved people? And are there other ways to research the perspectives of those who have been enslaved?

The voices of enslaved people

In the early modern period, the Netherlands played a major role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. As a result, Dutch archives contain numerous documents about slavery and the early modern slave trade. While a great deal of research is already being done on slavery (for example, the 2021 book Slavernij (Atlas Contact) and the Rijksmuseum exhibition of the same name), archival documents contain many as yet unexplored stories about slavery in which the voices of enslaved people occasionally shine through.

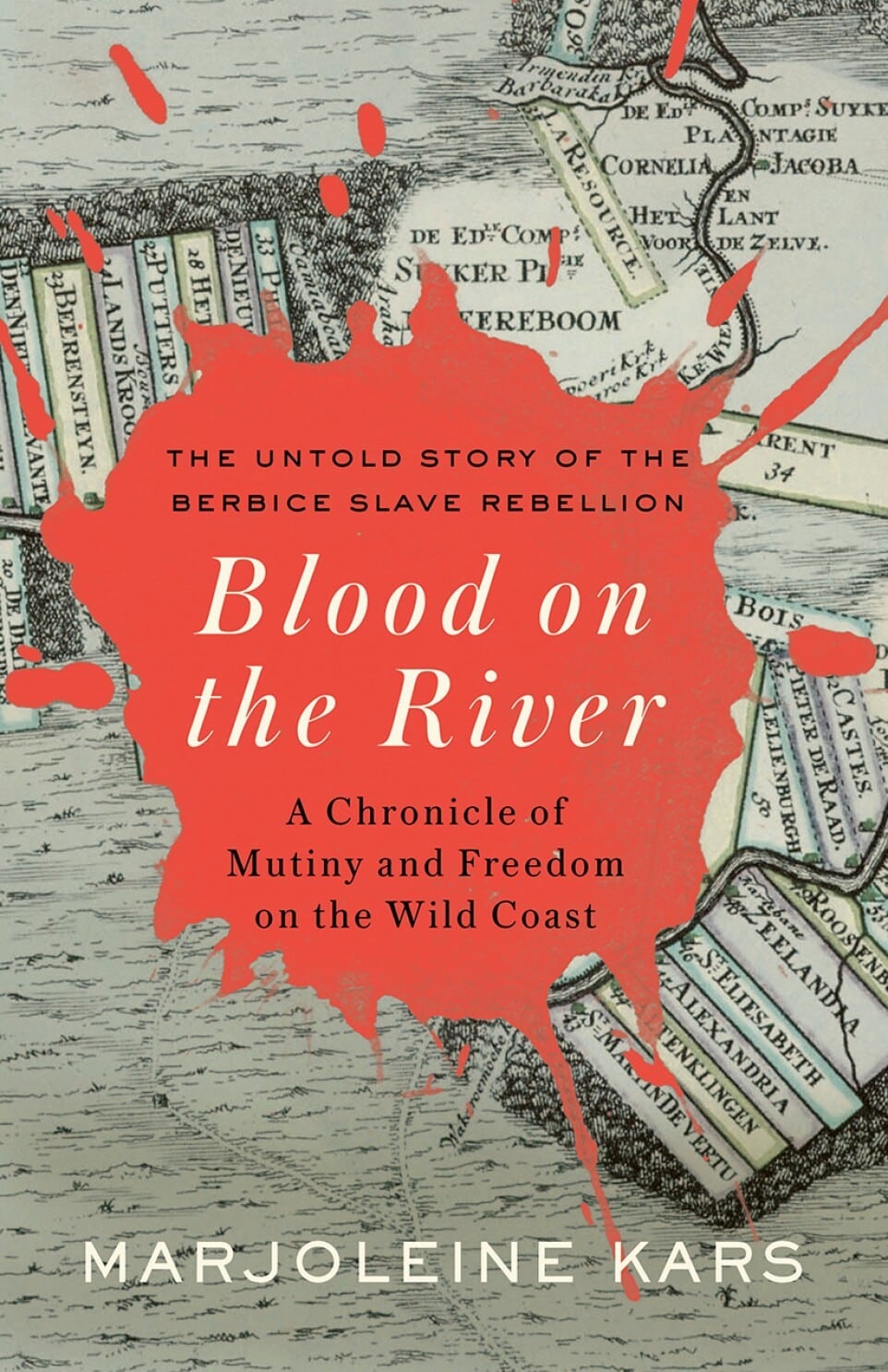

Historian Marjoleine Kars, for example, unearthed over five hundred pages that document interrogations of enslaved people, and even letters that they wrote to the Dutch authorities. In her book Blood in the River (Atlas Contact, 2021), Kars parses through these documents to shed light on the great slave revolt in Berbice (now Guyana) in 1763. During this revolt around 5.000 enslaved people took control of the country for over a year. By combining multiple sources, Kars was able to describe the lives, thoughts, relationships, and culture of the enslaved people involved in the uprising.

It is often much more difficult to examine lives in detail because there is little information in preserved documents and the voices of enslaved people are not often directly accessible. At first glance, documents paint a very fragmented picture and raise many questions. Such is the case, for example, in the story of the enslaved man Laquais. In the notarial archives in Amsterdam, one can find an insinuation (a notarized call to fulfill an obligation that puts pressure upon the receiver) that was filed by a certain André Renouard. In 1770, Renouard had taken Laquais from Suriname to the Republic, where he was expected to continue to serve Renouard just as he had done in Suriname. According to the notarial deed, Laquais did not return home to Renouard on 13 May 1772. The next day, Renouard “broadcast” Laquais’ name throughout the city and thus learned that Laquais may have been at the home of a certain Fredrik Guillaume. So, on 15 May, that is where he went to reclaim Laquais. Contrary to expectation: Guillaume refused. In June, Renouard returned with a notary. He demanded that Laquais come back to him and threatened to take him to court if he did not.

View of Amsterdam with ships on the IJ. Laquais was taken by ship to Amsterdam, which was a completely foreign world for him.

View of Amsterdam with ships on the IJ. Laquais was taken by ship to Amsterdam, which was a completely foreign world for him.source: NL-SAA, Beeldbank, by Georg Balthasar Probst and F.B. Werner, circa 1700

What had happened to Laquais? Had he been kidnapped and locked up in Guillaume’s home, or had he run away from Renouard of his own accord and sought refuge with Guillaume? Unfortunately, we don’t know the answer. Nevertheless, the short notarial deed provides a small insight into the life of Laquais. He had been taken by ship from Suriname to a country that was probably unknown to him. Although slavery was officially banned in the Republic, enslaved people were regularly taken from the colonies, both from the Atlantic and from Asia. It is estimated that hundreds of enslaved people were brought from Suriname to the Republic over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, of whom Laquais was clearly one. Although they now resided in the Republic, the deed demonstrates that Renouard continued to see Laquais as his property. He not only demanded that Laquais return to him, but even wanted to go to court to claim compensation for the “costs and damages” incurred for his loss.

Combining digital methods and archival sources

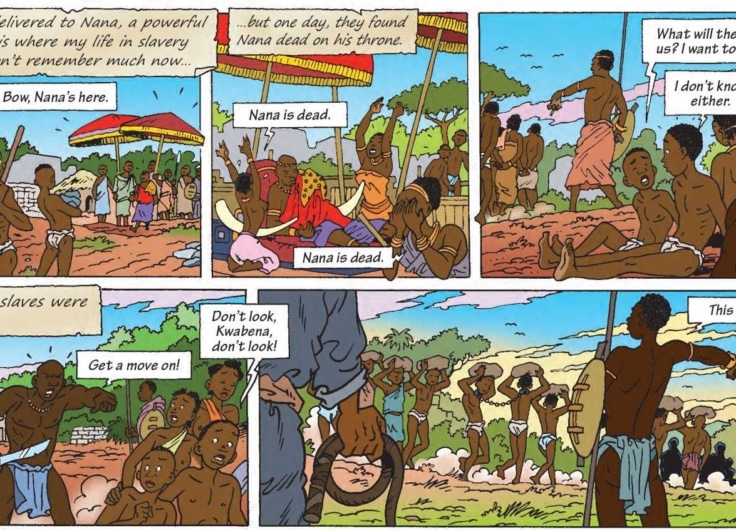

More and more researchers are now combining various colonial sources to tell the story of slavery from the perspectives of enslaved people. Historian Ramona Negrón, for example, has examined the lives of children who lived in slavery, and their broader role in the slave trade. Bringing together various sources – slave trade contracts and crew and surgeons’ journals that were kept on slave ships – she has reconstructed the experiences of enslaved children during the slave trade. Children were separated from their parents and other relatives in Africa and then transported to one of the colonies. If they survived the journey (many children and babies died on the way) they would never see their relatives again. Negrón concluded that the number of enslaved children aboard slave ships is probably higher than first thought, because slave traders were also interested in buying and selling children. Her work shows that existing sources, though compiled by slave traders, can also be used to illuminate the perspectives of enslaved children (and adults).

More and more researchers are now combining various colonial sources to tell the story of slavery from the perspectives of enslaved people

The digitisation and indexing of more and more archives has been an important development in helping to surface new stories about enslaved people. A good example is found in the Amsterdam City Archives, where the notarial archive is currently being indexed by the VeleHanden.nl platform – a crowdsourcing project in which civilians participate. Volunteers enter and verify all kinds of data like the names of people and places, which makes it possible to search for an ever-growing number of individuals. The aforementioned Aspasia and Laquais are both examples of enslaved people whose stories have emerged from this notarial archive. There are already many more stories to be found, and the number continues to grow.

Another essential improvement in the digitisation and indexing of archives is the ever-improving quality of Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR), a process in which the computer learns to search in handwritten texts – quite the challenge when it comes to texts in old manuscripts that are sometimes difficult for people to read. Although there is still a lot of room for improvement, HTR already ensures that researchers can search for the names of people and places, professions, or other terms in the vast archives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the West India Company (WIC), for example. This makes it possible to conduct research in a new way, a way that includes a multi-vocal perspective on the history of slavery.

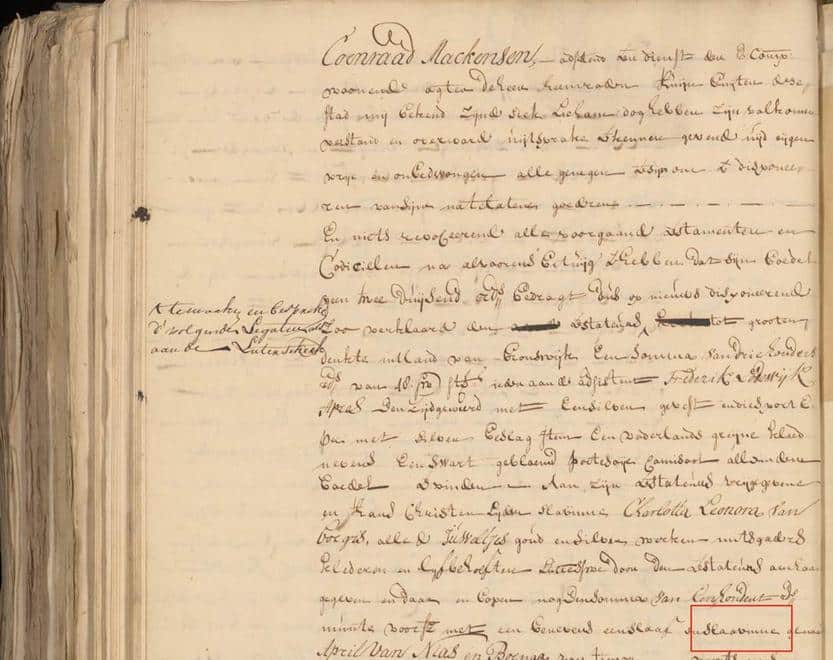

Document of the Unsilencing the VOC Testaments project

Document of the Unsilencing the VOC Testaments project© National Archives

The Unsilencing the VOC Testaments project by academic researchers Charles Jeurgens, Giovanni Colavizza, and Mrinalini Luthra is another good example of how digital methods help to explore the perspectives of enslaved people. These researchers also engaged students from the University of Amsterdam to help with the project. The VOC was one of the largest employers in the Republic. It employed thousands of seamen and soldiers, as well as craftsmen, pastors, and officials. For these men, living and working in early modern Indonesia was not without danger: the chance of dying from illness or an accident was high. That is why many VOC employees had their wills drawn up. These wills have all been preserved and can be found in the collection of the National Archives. With the help of HTR, those wills have now been made completely searchable, and information can be found about (among other things) enslaved people. They are often mentioned in wills, for example as heirs.

The traces of enslaved people are, in fact, ubiquitous throughout Dutch archives, but they are not always easy to find. Moreover, sources are often written from the perspective of the coloniser. And yet it is still possible to access the perspectives of enslaved people. By combining multiple sources from different archives, by reading “between the lines” and by developing and using new digital methods such as HTR, a multi-vocal perspective of the past can still be presented.