‘Ode to Antwerp’ Shows the Shared History of Flanders and the Netherlands

The exhibition Ode to Antwerp at Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht explicitly presents old masters from the Low Countries and not from Holland or Flanders. How did this expo come about, and what does it say about the cooperation between the museums in the Low Countries? “For foreign curators, the distinction between Flanders and the Netherlands is indiscernible.”

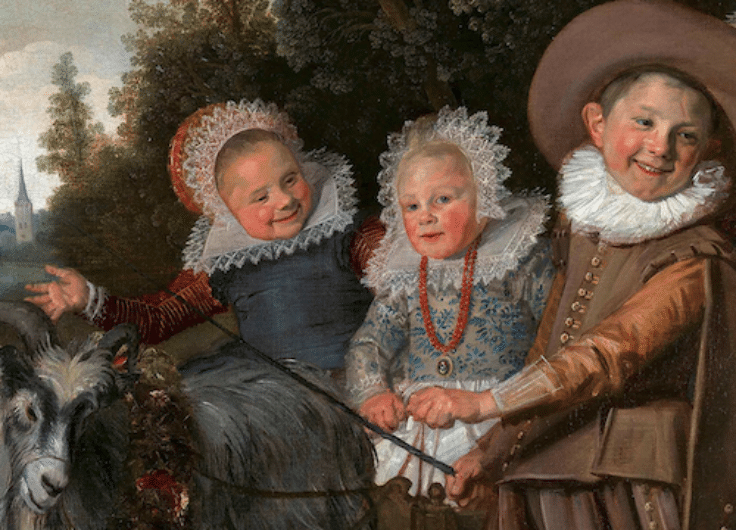

On 11 May 2023, Dutch King Willem-Alexander opened the exhibition Ode to Antwerp in Utrecht amid much enthusiasm. Is a member of the House of Orange’s interest in Antwerp a late act of atonement after three centuries of blockade of the Scheldt? In any case, it seems like something noteworthy is taking place, as the Dutch are particularly interested in the roots of Antwerp. Presenting Flemish and Dutch masters such as Maerten de Vos, Frans Floris, Frans Hals, Peter Paul Rubens and Rembrandt van Rijn, the exhibition at Museum Catharijneconvent shows that the heyday of Dutch painting would not have been possible without Antwerp in the sixteenth century. Sounds from Brabant reverberated abundantly in the studios in Haarlem, Delft and Amsterdam.

“Ode to Antwerp is a unique exhibition, because it shows that paintings from the Low Countries emerged gradually,” says Paul Huvenne, former director of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA). “That art historical insight is growing. In 1986, the Rijksmuseum held the exhibition Art Before the Iconoclasm: Northern Netherlandish Art 1525-1580. Back then, not even half a room was devoted to Antwerp. But the distinction between the north and south is completely artificial and actually makes no sense. It is more an art historical projection than reality. Ode to Antwerp is a recognition of our ‘Dutch’ identity, also within Europe: the Low Countries are one of the founders of modern Europe.”

Former museum director Paul Huvenne: 'Ode to Antwerp is a recognition of our "Dutch" identity, also within Europe: the Low Countries are one of the founders of modern Europe'

That sounds impressive. “Amsterdam could have never become so big without Antwerp,” curator Micha Leeflang concurs. “We have always wanted to work with the shared identity of the Netherlands and Belgium,” says the ebullient specialist in sixteenth-century Antwerp painting, who obtained her doctorate on Joos van Cleve, a painter from the Southern Netherlands who worked in Antwerp. “When it comes to Dutch masters of the seventeenth century, Frans Hals is always in the top three. He spent four years of his life in Antwerp. The style of Frans Hals is what we now label as ‘Dutch’, but actually it’s very much from Antwerp.”

Ties continued after 1585

How did things go back then at the end of the sixteenth century? The migration was not only religiously driven, but also economically, as the people of Antwerp lost the Scheldt after the Fall of Antwerp. The trade route was hermetically closed off, and that was advantageous to Amsterdam. “It is a complicated story, which I think is better known in Flanders than in the Netherlands,” says Leeflang. “Of course, many artists stayed in the south, and there was also a lot of interaction after 1585.”

A central work in the exhibition is the Panhuys panel from 1574 by Maerten De Vos, on loan from the Mauritshuis with the official name: Moses Showing the Tablets of the Law to the Israelites, with Portraits of Members of the Panhuys Family, their Relatives and Friends. “De Vos converted to Catholicism,” says Leeflang. “More painters did that: there was a lot of work in Antwerp due to the Counter-Reformation, and non-Catholics weren’t able to sell their homes. Big names like Rubens, Jordaens or Van Dyck simply stayed put. The expo also devotes attention to them – a trip to the emerging Antwerp baroque.”

The Panhuys panel by Maerten De Vos, 1574, Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht

The Panhuys panel by Maerten De Vos, 1574, Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht© on loan from the Mauritshuis

Curator Micha Leeflang believes she owes everything for this exhibition to Fernand Huts, the head of The Phoebus Foundation of Katoen Natie, by far the largest lender. “When I contacted them, I was sent a van with a stack of books a metre and a half high,” she says. “During Covid, it was also the only place I was allowed to go. I found the depot space and the collection with the studio incredibly impressive. I literally cried when I walked in. I felt like a kid in a sixteenth-century art candy store. I found art there that had been sold at auctions to ‘a private individual’. That is how The Phoebus Foundation became my salvation.”

Curators of CODART: Mainly Dutch network

The Phoebus Foundation as deus ex machina for a Dutch museum rather than a Flemish or Brussels sister museum? Art historian Koenraad Jonckheere (UGent) is the author of the magnum opus Another History of Art: 2,500 Years of European Art History. He has a podcast about the Iconoclastic Fury and has published extensively on the religious and economic motives behind the migration to the north after the Fall of Antwerp in 1585. His publications formed the basis for Ode to Antwerp, and Jonckheere co-wrote the catalogue. He offers insight into museum relations north and south of the border.

Micha Leeflang, Paul Huvenne and Sven Van Dorst at the Phoebus Foundation

Micha Leeflang, Paul Huvenne and Sven Van Dorst at the Phoebus Foundation© Saskia Dendooven

“As far as I’m concerned, there is no exchange between Flemish and Dutch museums to speak of,” says Jonckheere over a coffee at S.M.A.K. in Ghent. “There is the worldwide network, ‘CODART – Dutch and Flemish Art from the Low Countries’, but the input from Flemish cultural policy was never optimal. CODART was set up twenty-five years ago by the American Rembrandt connoisseur, Gary Schwartz. Museum Catharijneconvent approached me because I have written a lot about sixteenth-century Flemish art. I spent part of my career in Amsterdam, so I am also somewhat familiar with the Dutch art world. In the Netherlands, culture is more strongly supported, although when it comes to old masters, we are now catching up thanks to Flemish culture minister Jan Jambon.

Jonckheere believes that it’s typically Flemish that VISITFLANDERS is regarded as the art promoter and sponsor. “This isn’t ideal,” says the art historian. “There should be much more collaboration with culture. For example, a council of experts that also consists of museums and universities. I also think that’s a predicament in Flanders: millions are invested in art history research, and a lot of money goes to art education, but there is little interaction between the museums and the academic world. This is why new ideas often don’t reach the public.”

Need for a more stimulating policy

Paul Huvenne is more optimistic about the interactions between Flemish and Dutch museums. “I have always worked very efficiently with Dutch museums. A lot depends on the director, and personal relationships are decisive. I was on the board of directors at the Rijksmuseum, and I am a co-founder of CODART. Abroad, you saw the distinction between curator and conservator from the Netherlands or Flanders disappear automatically. Outside our borders, the different schools are not separated either. Rightly so.” But he shares Jonckheere’s criticism of the government’s role: “I added a Flemish branch to CODART, but Flanders doesn’t really have a stimulating government policy.”

The Phoebus fellowship: a member of an international team at work in the restoration studio.

The Phoebus fellowship: a member of an international team at work in the restoration studio.© Saskia Dendooven

Marianne Van Boxelaere, the deputy diplomatic representative of Flanders in the Netherlands, also outlines adequate cooperation. “Conservators from Flemish and Dutch museums know each other’s collections. They lend artworks to each other to make our precious heritage accessible to as many people as possible. The Frans Hals Museum recently showed loans from Flanders in the exhibition Newcomers:

Flemish Artists in Haarlem 1580-1630 (September 2022 – January ’23, WDH), and the exhibition Ode to Antwerp: The Secret of the Dutch Masters at Museum Catharijneconvent would not have been possible without the loans from Antwerp. Flanders and the Netherlands are also joining forces through CODART, the international network for museum curators of Early Netherlandish, Dutch and Flemish art, which has six hundred members from three hundred museums spread over fifty countries. It contributes to making Dutch and Flemish art visible in the world.”

The Phoebus Foundation: Without borders

It is, however, a shame that Flemish museums have fewer resources than Dutch museums. Additionally, there are no organisations in Flanders that actively purchase art for museums, such as the Rembrandt Association in the Netherlands. Without patronage for publicly owned art, a wealthy private foundation such as The Phoebus Foundation does indeed come to the rescue.

This spring we were able to take a backstage look at the art collection of Burcht Singelberg, as owner and port chief Fernand Huts named the Katoen Natie building in the middle of the Antwerp port area. Aptly, it stands exactly on the same spot on the left bank of the Scheldt where the Spanish Governor and Duke of Parma, Alexander Farnese, managed to force the surrender of Antwerp in 1585.

Flemish Prime Minister and Culture Minister Jan Jambon: 'Culture connects countries, and anyone who looks around here sees how strong our shared history is'

We get to see some works that are temporarily moving to the expo in Utrecht. “We are starting Ode to Antwerp with works by Joos van Cleve, strongly rooted in the tradition of the Flemish Primitives with their Italian influences,” says curator Micha Leeflang as we walk around the perfectly temperature-controlled studio where an international collection of restorers is diligently at work.

“Antwerp art is mainly represented by the Mannerists with their crowded and colourful scenes. Joos van Cleve, Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Quinten Matsys are the three greats of the first generation. By 1600, artworks often became enormous. The Phoebus Foundation was of tremendous help in getting them into the museum, for example, by putting them in a different frame so that they could fit through our lift. This way, we can show top works such as Cain and Abel by Frans Floris.”

'Cain and Abel' by Frans Floris is one of the top works at the 'Ode to Antwerp' exhibition.

'Cain and Abel' by Frans Floris is one of the top works at the 'Ode to Antwerp' exhibition.© The Phoebus Foundation / photo by Marco Sweering

Free loans to museums

While behind the window at the Port of Antwerp, European freight traffic rumbles past the warehouses, head restorer Sven Van Dorst explains how the foundation works: preserving cultural heritage and making it accessible are its objectives, but so is scientific research. “The Phoebus Foundation has masterpieces listed – as defined in the Flemish masterpiece decree – but does not collaborate with the Flemish government or museums to purchase them. We are allowed to loan them abroad. The Sun Painter by Frits van den Berghe (1921), for example, is on display in The Hague in an exhibition on Flemish Expressionism (25 March to 20 August 2023, WDH). We simply have to request permission for that work to cross the border temporarily. Our collection, Old Masters of the Southern Netherlands, forms a gap in many Dutch museums. We lend works to museums free of charge, even for extended periods.”

Dutch ambassador Pieter Jan Kleiweg de Zwaan at the Phoebus Foundation

Dutch ambassador Pieter Jan Kleiweg de Zwaan at the Phoebus Foundation© Saskia Dendooven

Pieter Jan Kleiweg de Zwaan, the Dutch ambassador to Belgium, listens attentively to Van Dorst. Is culture also a diplomatic tool, as Flemish Prime Minister and Culture Minister Jan Jambon says? “Culture connects countries, and anyone who looks around here sees how strong our shared history is,” says Kleiweg de Zwaan. “The history of the emergence of the Netherlands as a nation-state partly has its roots in Antwerp. Noteworthy is that The Phoebus Foundation is a private initiative. This proves that government intervention is not always necessary to forge and strengthen strong cultural ties.”

Purchasing power and exposure

The fact that Fernand Huts and his enthusiastic chief of staff Katharina Vancauteren are allowing Dutch journalists (and one stray Fleming, yours truly) into the depot for the first time, is also a solid PR exercise aimed at a Dutch audience about the museum in the Boerentoren in Antwerp, which is still under construction.

A philanthropic foundation based on the Anglo-Saxon model, such as the Getty Foundation or Fondation Louis Vuitton, set up by a port chief who has placed his foundation offshore. What does Koenraad Jonckheere think of The Phoebus Foundation as the largest lender for Ode to Antwerp?

“Phoebus has enormous purchasing power,” Jonckheere agrees. “For the past ten years, it has dominated the art market of the Flemish old masters. It now has a very wide collection, from which I’m not sure if every piece is worth buying. But it is also quite generous, unlike many museums, due to staff shortages and practical problems. Phoebus actively seeks exposure. It is and will remain a private initiative, but having our own museum will certainly change our museum landscape for the better and will have an impact in Flanders and the Netherlands. I am very curious about the future museum’s total concept in the Boerentoren.”

Flanders: Time to look to the north

How many times has a member of the Belgian royal family cut ribbons at an exhibition about the Amsterdam of the Golden Age? Why won’t there be an ‘Ode to Haarlem’ in, say, Ghent or Bruges? The interest from the north seems greater, and that is unjustified, also from a Flemish viewpoint. Pieter Pourbus was born in Gouda and died in Bruges. Many sixteenth-century contemporaries followed the same course and travelled to the south.

“The interest from the Netherlands is precisely due to the division of the Low Countries in the sixteenth century and the brain drain from the south,” says Koenraad Jonckheere. “The commercial spirit of Antwerp was copied and improved in Amsterdam. It is interesting that even after the exodus, things were not so bad in the art world of the south until at least 1640 and the death of Rubens, who stood above his contemporaries in terms of production, in both the north and south.”

Koenraad Jonckheere concludes: “What fascinates me is that the exchange of ideas continued in that period, with a peak during the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609-1621). Even after the split, we remained one country. There were just as many Catholics in the north as there were Protestants in the south. Rubens travelled to Holland, met Humanists such as Grotius, Heinsius and Baudius in Leiden and visited Goltzius in Haarlem. He brought Northern Dutch artists such as Pieter Soutman – who were partly responsible for the success of his studio – to Antwerp. Indeed, you could also set up a wonderful exhibition the other way around.”

The exhibition Ode to Antwerp

runs until 17 September 2023 at the Museum Catharijneconvent