On the Crossroads of Physics and Art: Isabel Fredeus’ Sensory Work

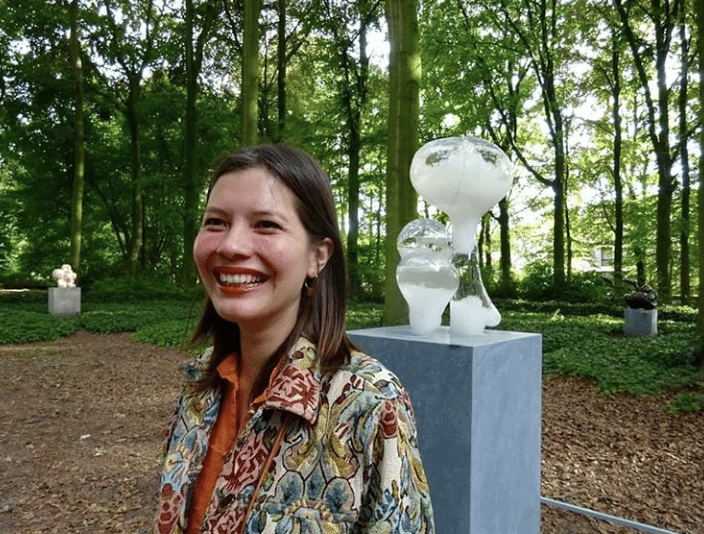

Hailing from Antwerp, Isabel Fredeus (b. 1991), has only been around as an artist for a few years. Nevertheless, she has won a number of important prizes. Fredeus’ work includes sculptures, videos and interventions, preferably in elastic manipulable materials. In her work, natural processes and the laws of physics lead to compelling, lyrical artefacts.

Isabel Fredeus

Isabel Fredeus© instagram Isabel Fredeus

Hilde Van Canneyt: June is evidently your favourite month: in June 2015 you won the Lucas Award, and in June 2018 you won the Middelheim The Promotors Young Artist Prize.

Isabel Fredeus: ‘The first prize was for my end of year show at the Sint Lucas School of Arts in Antwerp. That was an important year for me because I was working with painting until the third year of my Bachelor’s degree, and it was only when I was doing my Masters in Liberal Arts that I moved over to installation.’

Was painting no longer exciting for you?

‘I still find painting exciting, but I was always more interested in the process of painting, rather than the final result. Painting was really interesting to me, right up until the point when the paint dried. That’s how I ended up having a whole phase of action painting. That transition grew very organically. Frist I began making videos where, for example, balloons filled with paint would explode. Or I’d make my studio into an installation where I would rank all of my paint according to their colour codes. I tried to do all sorts with the medium, without actually creating a painting. At the time, Marcel Broodthaers’ piece La pluie really inspired me to work with time and transience.’

Were the sculptures that you exhibited a derivative of your painting process? You presented the whole spatial installation under the title To set the course. The tension between the two and three-dimensional is also an important detail in that.

‘For me the sculpture Letting go was the transition from painting to installation. I drilled holes in the top of a window’s double glazing and dripped varnish through them so that the paint flowed into the space between the two pieces of glass. Because of gravity, the paint dripped equally in two parallel lines down the two sides of glass. That was the starting point for everything else. After that I began to think intensively about the painting as a window and in that way I made a number of different pieces.’

Isabel Fredeus, Letting go, lacquer paint between glass, 60-130cm, 2015

Isabel Fredeus, Letting go, lacquer paint between glass, 60-130cm, 2015© Isabel Fredeus

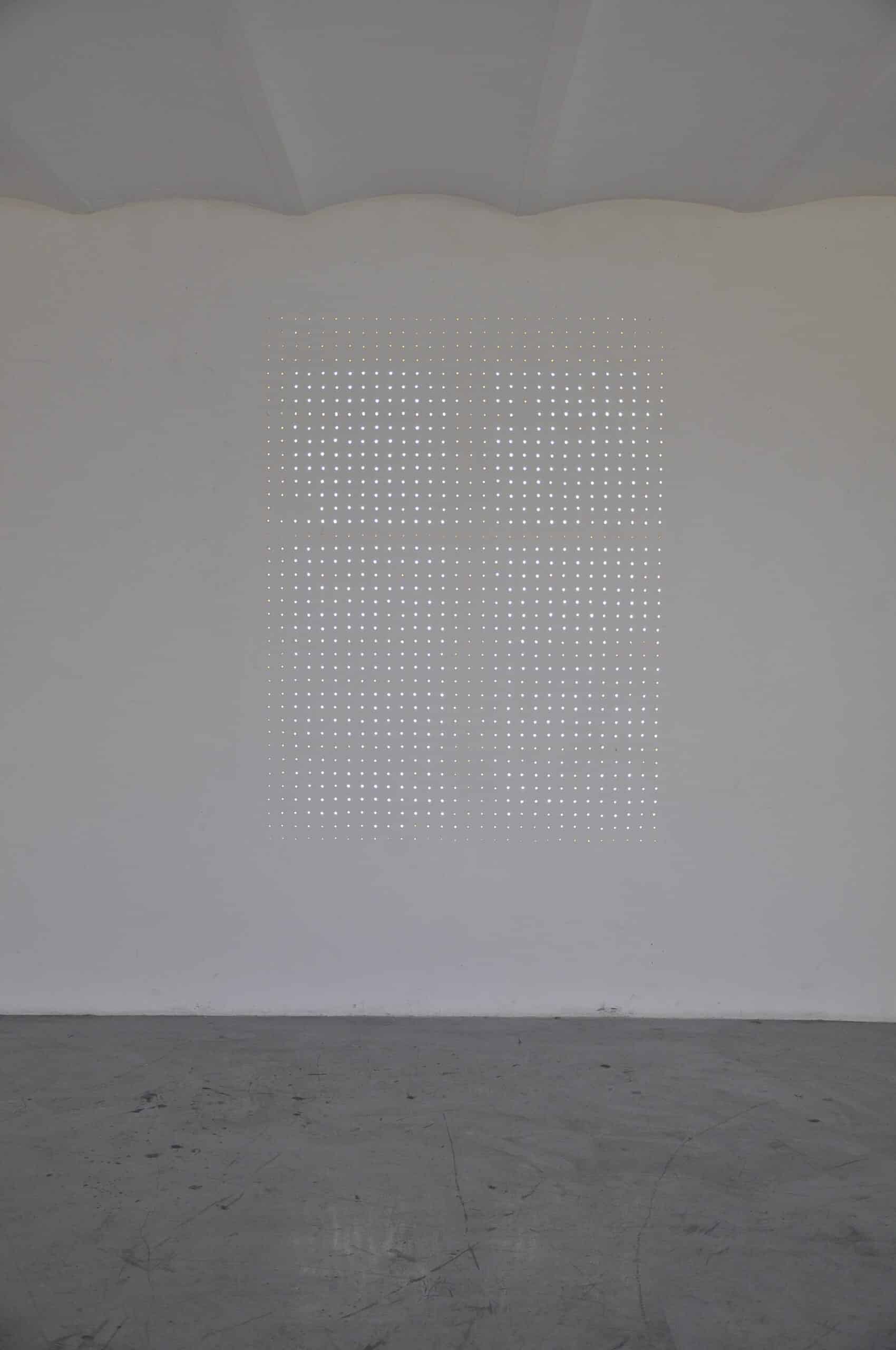

‘For this end of year show I drilled holes into the exhibition wall. When I hammered a nail into the wall I found that light came through during the day. I wondered whether there was a window behind the wall, and there was. Through those little holes in the wall, I gave the window its form back. That was interesting to me – I was confronted with an image that was changing – during the day it would provide natural light, and in the evening they were black holes. One thing often leads on to another in my work. I think it’s important to improvise within a specific structure.’

Isabel Fredeus, Letting the outside world in, holes in wall letting in natural light/darkness, 150-200cm 2015.

Isabel Fredeus, Letting the outside world in, holes in wall letting in natural light/darkness, 150-200cm 2015.© Isabel Fredeus

Your work is partly about tactility.

‘The sensory is very important. Measuring is an aesthetic thing for me. You don’t gain control over something just because you measure it. While I want the viewers to feel a desire to touch my work, it’s not the sole aim. I’m interested in the tension between my work and the viewer.’

I suspect someone may find it difficult to know what the work is about if there is no accompanying text. What do you expect from the viewer?

‘For me it’s about the experience itself – you don’t have to know exactly what it’s about. I hope that the work simply does something by making the viewer ask themselves questions: ‘What is going on here?’ Of course there are many people who have questions when I exhibit work. I realise that my work isn’t always readable, but I do attempt to provide ‘enough’ visually.’

Before you knew it, you were competing for The Promotors Young Artist Prize in Antwerp’s Middelheim Museum. You exhibited Under the weather which is a glass sculpture positioned on a plinth. The sculpture is made with hand-blown storm glass and is an enlargement of a traditional measuring instrument used to calibrate human activity to changing weather conditions, as often used on ships.

‘I had been interested in glass for a while but I was far from being able to work with it. I really enjoy working with transparent materials. I’ve also been working with water for a while, as well as silicone and epoxy – but that’s not healthy. I’ve also wanted to work with manipulable glass for some time. Glass has fluidity similar to that of water. For example, glass has no melting point, but it does have many differing appearances. It’s an amorphous solid. For ages I’ve been interested in measuring instruments: spirit levels, pendulums, objects with which people have tried to capture pure physics. In itself, one of these weatherglasses is an old-fashioned measuring instrument, but then much smaller than what I have made. People using them would look, in a small amount of liquid, at the crystallisation. I made the prototype, the design, and the mould, and I blew the glass at the Nationaal Glasmuseum in The Netherlands with my glass teacher Luc Debruyne, and Gert Bullée and his team, because this wasn’t technically feasible in Belgium.’

Isabel Fredeus, Under the weather, stormglass sculpture, 2018

Isabel Fredeus, Under the weather, stormglass sculpture, 2018© Ans Brys

You had to take into account all weather conditions. On top of that it had to stand on a plinth, have some kind of inherent meaning, and

be visually beautiful.

‘People think that glass is very fragile, but really glass is quite well suited to gradual temperature changes. What I like about the work is that it is constantly changing. When it’s good weather, a different crystal forms to when the weather is bad. It is not a static image.

In all my work, I consider the matter of process very important. That is why I try to document process as much as possible. And that process, that research, is something that I very much like to share. At the same time, of course, I want to preserve a sense of illusion for the viewer. My work in Middelheim is now at The White House gallery in Lovenjoel for an exhibition. It’s the first work for which I have had to take into account so many different factors and people.’

What are the thematic and formal elements that you work with?

‘Natural phenomena like sunlight and water excite me, and I like to put these basic phenomena centre-stage; the same holds for sensory phenomena. I’m especially interested in how you can represent a natural process in a work. Sometimes that coincides with an object’s inherent attractiveness. From there, I try to derive a certain starting-point. Think, for example, about how a snowflake grows, or about the seasons, day-night, melting- and freezing points, drying, and about the senses and their electrical stimulations. Consider filters and sensors: how do we filter our environment and through which channels do we experience stimulation? A good example is my work Fingerspitzengefühl, hand sculptures that I based on the ideal contact between a hand and a stone. Or, for example, water in progress, a work that’s about time, evaporation and the properties of water.

© Isabel Fredeus

With a light, scholarly view, I work on physical and biological processes that I try to distil into an aesthetic essence. With this knowledge I try to call certain beliefs into question. This is why I like to link my work to measuring instruments. I also work a lot with the filtering of environmental stimuli. And that brings us close to the phenomenon of experience. This leads to my research question ‘why does that excite or stimulate me?’ This is why I try to play with the connotations that materials have. What’s so interesting about these physical laws is that everything is set in stone. There is no choice: no matter how high you jump, you will always land back on the ground. The micro- and macro-scales also make up part of my work. Irony and spirituality set up a kind of resonant questioning of scientific approaches. There are certain things that we simply cannot capture as mathematical fact.’

Which artists do you particularly admire?

‘I started out particularly into J.M.W. Turner, Cecily Brown, Cy Twombly, Andy Goldsworthy. Later I got to know about the work of Joëlle Tueurlinkx, Francis Alÿs, Edith Dekyndt, Eva Hesse, Martin Creed, Olafur Eliasson, Robert Fillou and Roman Signer. Alÿs showed me the poetry of various simple actions. What intrigues me in Tuerlinckx’s work is above all her indexing: how she has devised a system that gives a place to all of the details of her artistic oeuvre. Roman Signer brings together humour, tension and science in his work.’

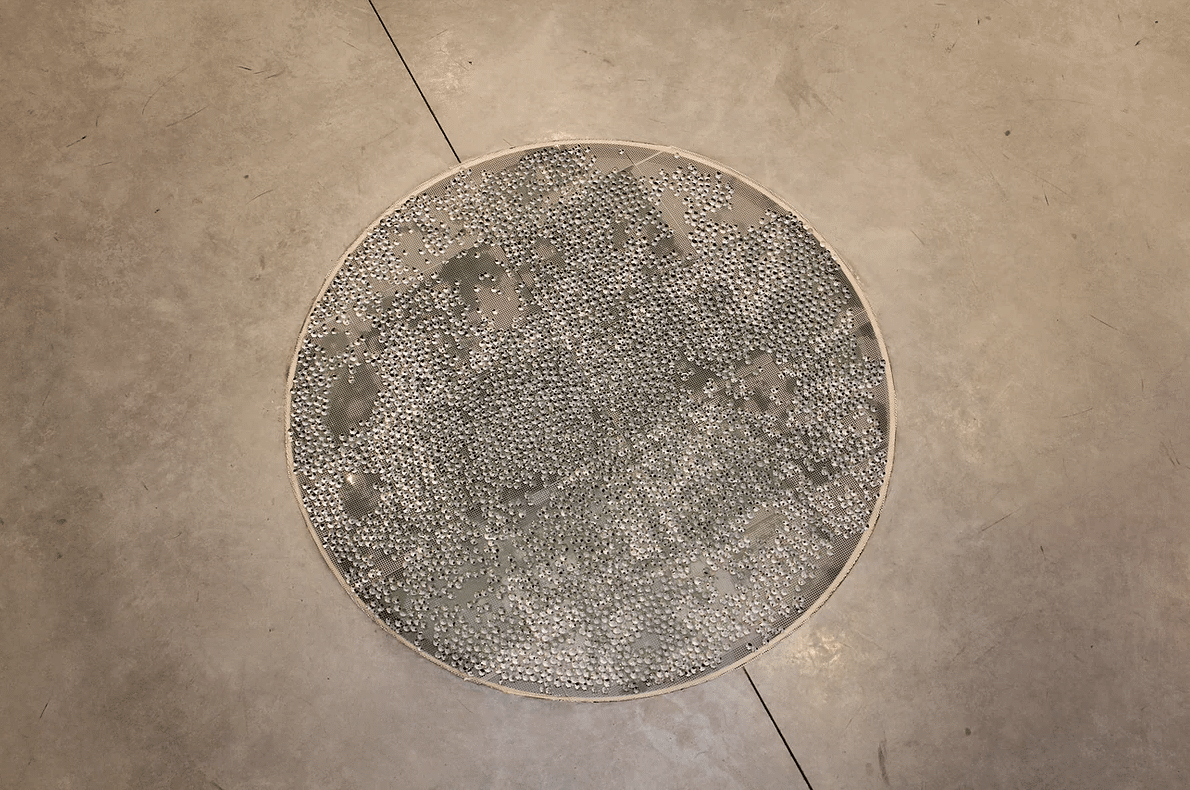

Isabel Fredeus, Mutable Surroundings#1, time-based installation, hydro-polymeer balls, water, plastic grid, glass, 120 cm ϕ, 2018

Isabel Fredeus, Mutable Surroundings#1, time-based installation, hydro-polymeer balls, water, plastic grid, glass, 120 cm ϕ, 2018© Isabel Fredeus

What is ‘sculpture,’ and by extension ‘art,’ for an artist working in 2019?

‘I am of the opinion that an artist should not ‘have’ to do anything. But whatever you make, or at least from the moment that you show it, all that you do is political. You’re giving a public opinion. Exhibiting is conveying a sense of what is going on in your head today. Whether you comment on it explicitly or not. Not commenting on something is always already to take up a position, whether consciously or not.’

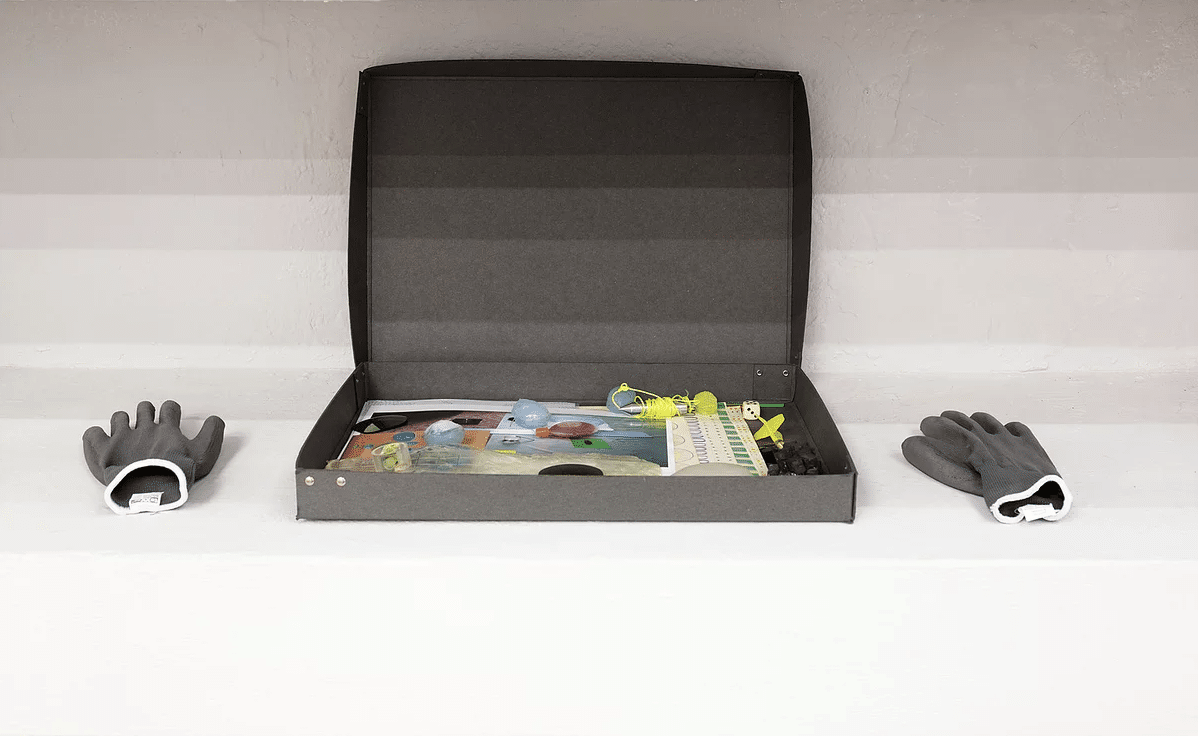

Isabel Fredeus, The Box, A collection of thoughts, mixed media, 2016

Isabel Fredeus, The Box, A collection of thoughts, mixed media, 2016© Isabel Fredeus

What should we as viewers think about your work The box, for example: two white gloves next to a black cardboard box filled with material?

‘For me, modes of presentation is also a way of doing research. This work is really a small, staged toolbox that I wanted to show. So there’s a pendulum in it, little tubes with liquid, a photo, a letter addressed to the so-called buyer with an archive of my thoughts… The artwork functions as a little diorama into my thought processes.’

How do your titles relate to your work?

‘Through my titles, I try to get put some irony into my work. Sometimes they’re a little melancholy in nature. I do this to pull the works back to the human, and to forge a relation between the immeasurable and the measurable. What is the relation between love and life to gravity and polarisation? Why is it sometimes funny when something falls?’

Finally, what does your ideal day in the studio look like?

‘It’s a day in the studio where I can go on an exploratory journey, and can surprise myself. When I have time to think about time, and can afford to take a break every now and then for a cup of coffee and an exciting chat with my studio-mates.’