Otobong Nkanga Operates Like a Political Seismograph

Nigerian-Belgian artist Otobong Nkanga (b. 1974) is many things: she draws, performs, weaves tapestries, takes pictures and makes video and installation works. She is always searching for the connections between the world and bodies, poverty and enrichment, Africa and Europe, or how a mine in Namibia generates brilliant luxury in the West. A versatile, fascinating artist, her works are in demand from the Venice Biennale and Documenta Kassel to Tate St Ives and the Zeit Museum in Cape Town.

Born in Kano, Nigeria, Nkanga has been working out of Antwerp for over a decade. Still, she is better known outside of Belgium, notwithstanding exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp (M HKA) and the Centre for Contemporary Art Wiels in Brussels and her participation in the group show Ecce-Homo in Antwerp. She won the Belgian Art Prize in 2017, and was the 2019 laureate of Ultima, the Flemish Community’s cultural award.

Otobong Nkanga

Otobong NkangaIn 2019 Nkanga’s work was put centre stage at the Venice Biennale, followed by a solo exhibition at Tate St Ives in Cornwall. From Where I Stand was the first solo show by a female Black artist at any of the Tate locations. Another major solo exhibition, called Acts at the Crossroad, was staged at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art in Cape Town. Moreover, she was welcomed as the artist-in-residence at Gropius Bau in Berlin in 2019 and was awarded the Peter Weiss Award in Bochum, a German prize for cultural merit.

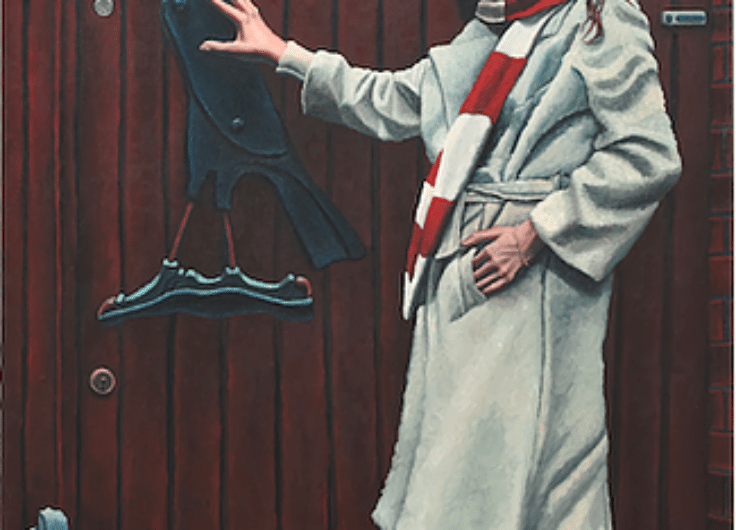

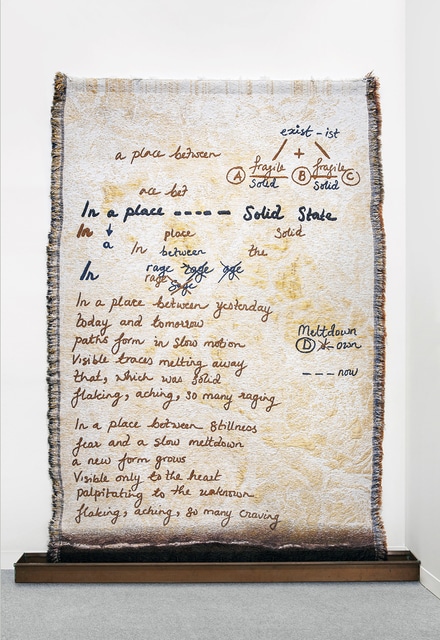

In a Place Yet Unknown, 2017

In a Place Yet Unknown, 2017© In Situ - Fabienne Leclerc

Nkanga – an alumnus from the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris as well as the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam – is conquering the world. It is the core subject of her practice: our world and how we treat it. Processes, connections and change are the three key concepts in her work. For example, In a Place Yet Unknown, a contemporary take on a tapestry, a black dye slowly eats away at the fabric, gradually changing its colour. Woven into the texture is a poem on transformation: In a place between stillness / fear and a slow meltdown / a new form grows / visible only to the heart.

These processes of material transformation reflect fundamental evolutions in society. Seemingly supported by incorruptible values while constantly changing, society in fact experiences decay while giving birth to new, young and different forms of life. ‘None of us live in an unchanging state’, says Nkanga. ‘Identity is fluid.’

The contagion of our thoughts and opinions

In her exhibition The Absent Museum in Wiels (2017), Nkanga presented a remarkable installation. Contained Measures of Shifting States is simple: a glass drum regularly lets out a drop of water that, by way of an aluminium groove, falls onto a hot plate and vaporizes. The metaphor is clear. By minimal means the artist invokes contemplation.

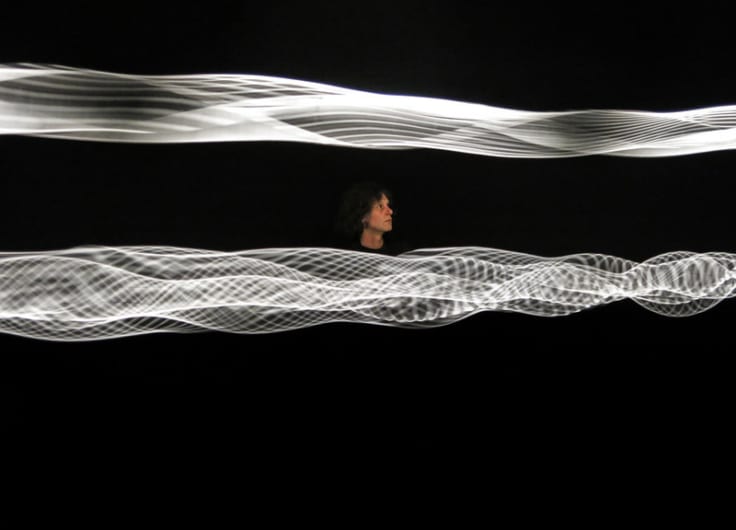

Veins Aligned, 2018

Veins Aligned, 2018© Ben Davis

The refinement Nkanga bring to each work is remarkable: her respect for recycled materials and her attention to detail. At the 2019 Venice Biennale her work received an honourable mention from the jury. For the Arsenale she created Veins Aligned: a 26-meter-long gleaming sculpture that resembled a human vein spilling over the floor like a river. Manufactured from local materials – Bolzano marble and Murano glass – and crafted in collaboration with local workers, it was another typical example of Nkanga’s practice.

Detail of Veins Aligned

Detail of Veins AlignedThe sculpture’s concept was inspired by a train journey from Verona to Bolzano. Nkanga saw the beautiful landscape and its fruit cultivation and became aware of the chemical products that enabled its existence. Chemicals that would, inevitably, enter into the water and air. Veins Aligned told the story of human veins, water and airways as they are slowly compromised. The Murano glass – the ‘river’ – atop the marble changed colour: from bright blue on one end, to red and black on the other. ‘The impurities affecting the glass are a reflection of our society,’ according to Nkanga. ‘They represent the contagion of our thoughts and opinions, similar to the division between white and black, fat and think, us versus them…A distinction imperceptible to children, only operated by adults.’

Broken places become monuments

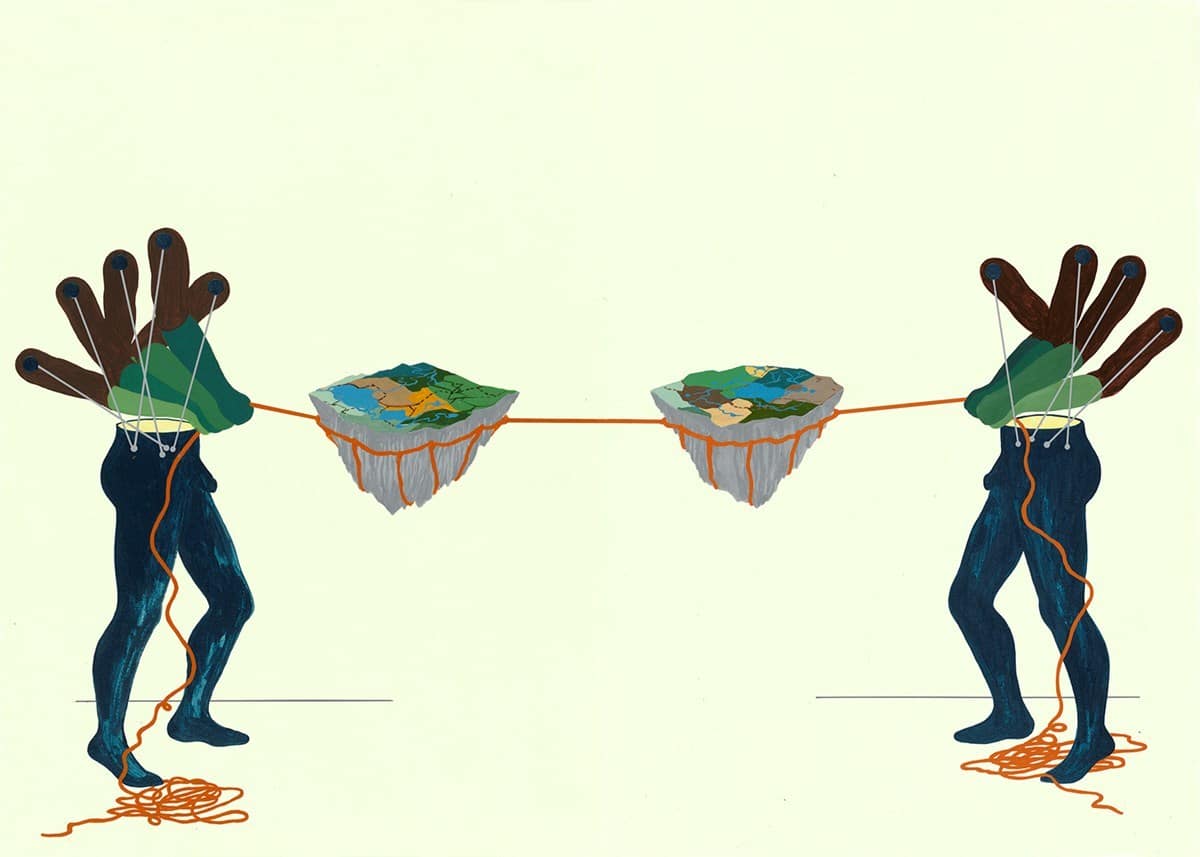

Social Consequences I: Crisis, 2009

Social Consequences I: Crisis, 2009© M HKA & photoclinckx

Nkanga is fascinated by the disastrous impact people’s activities have on our environment. Inspired by her own background, her artistic research focusses inevitably on colonial and postcolonial mining practices. For example, the excavation of ore and other raw materials can fundamentally change a landscape and its communities. It is a topic often expressed in her colourful and playful drawings. A series, titled Social Consequences, depicts robotic arms ending in scissors, hammers, pickaxes or needles. They smash and gather plants and trees, using them to feed people or produce new materials. Infinite Yield is the somewhat cynical title of a textile depicting a human figure in a mine drowning in the natural riches of the earth. It begs the question: are the earth’s resources really endless?

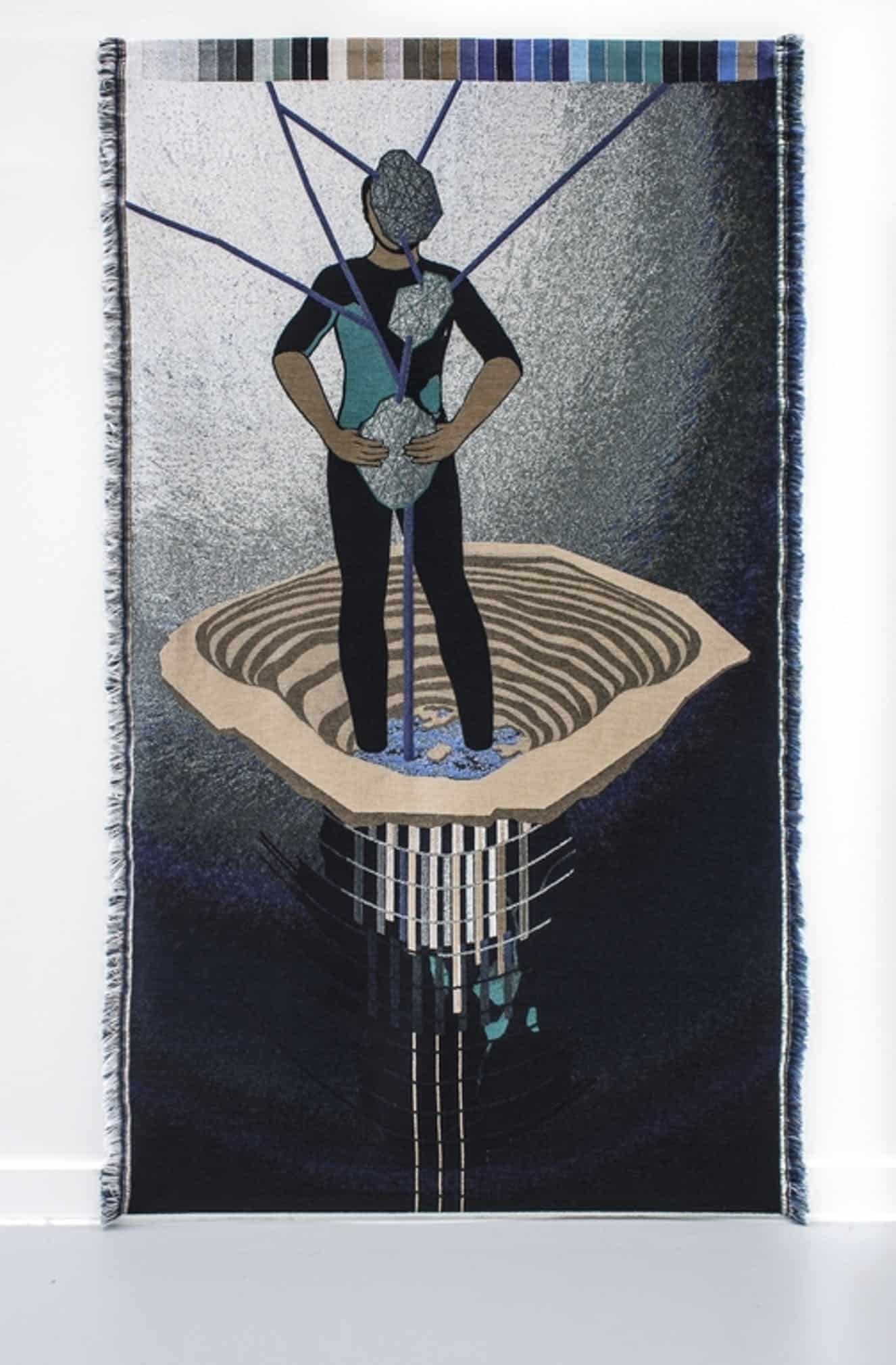

Infinite Yield, 2015

Infinite Yield, 2015© M HKA & photoclinckx

In 2015 Nkanga travelled to Namibia to visit one of the wealthiest mines in the world, for her work Tsumeb. The title refers to a small town that was exploited by the Germans from 1907 through the Green Hill Mine. The place was rich in minerals and ore, as well as copper, led, silver, gold and arsenic, that were smelted on site. The mine closed down in 1996 as ore became less profitable. Still, an active copper smelting oven remains in operation, affecting the local environment and the health of its population.

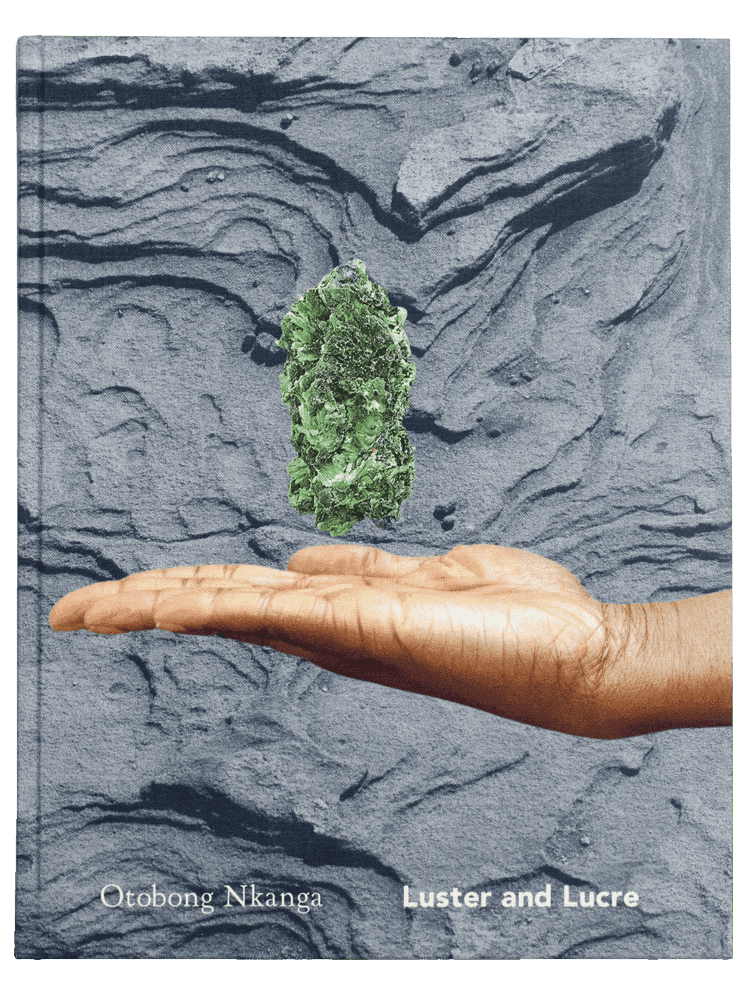

Luster and Lucre, Nkanga’s first monograph

Luster and Lucre, Nkanga’s first monographAs Nkanga rode the train to Tsumeb she realized the railroads had originally been constructed to transport ore from the mine to the harbour of Swakopmund. ‘The construction of that railroad must have cost blood, sweat and tears’, she recounts in her book Luster and Lucre. ‘The scars brought upon the land by people extends beyond Namibia. I realized the magnitude of the greed that led to these kinds of developments and exploitation. What does this do to the local population? What does this to us, who use these products? Do we even consider that these places are somehow connected? That, when a landscape gets mutilated in Namibia, its rocks shattered, an emptiness manifests someplace else?’

When she arrived in Tsumeb Nkanga did not find the Green Hill mine, but a large, gaping hole in the ground, surrounded by dilapidated buildings and a field full of contaminated ore refuse. Poisonous dust got picked up by the wind. The gleaming copper domes and stunning marble monuments in European capitals have left behind empty pits and damaged vistas, including in Africa. Places that are rendered invisible or obscured from our awareness. Nkanga argues that these places are the real monuments that remind us of the magnitude of this kind of destruction.

Her installation Tsumeb Fragments merges historic imagery from the Green Hill Mine with the artist’s own recordings of the current site. She offers pictures of the rocks and debris, a series of drawings and archival imagery from the local museum.

Tsumeb Fragments, 2015

Tsumeb Fragments, 2015© Gert Jan van Rooij

Inequality and power

The conviction that ‘everything is connected with everything else’ informed Nkanga’s participation in Documenta, a contemporary art event that takes place every five years, most recently in Kassel and Athens in 2017. In Athens she performed Carved to Flow, in which she produced black soap from oil, butter and charcoal derived from the Mediterranean, the Middle East and North and West Africa. It was a statement to the global logistics involved in producing something as simple as soap. After that, fifteen thousand pieces of soap were sold during performances in Kassel. Its proceeds allowed Nkanga to launch the third phase of the project: to replant the soap materials in Africa. Since then, she has launched a foundation concerned with circular economics in Akwa Ibom, Nigeria, bearing the same title.

Carved to Flow, Documenta 14, Neue Galerie, Kassel, 2017

Carved to Flow, Documenta 14, Neue Galerie, Kassel, 2017© In Situ – Fabienne Leclerc

Simultaneously, Carved to Flow was a way for Nkanga to expose how materials that were derived from plunder of cheaply bought eventually get sold for a much higher price, after having been shipped and processed. Seen in this way, Carved to Flow is a performance on inequality and power.

In the ‘politically’ engaged art of Nkanga everything is connected: what we do, build, buy, and attract always gets produced someplace else in the world, often with devastating consequences. Her work is born from a concern for the earth as one living organism, of which we are all an inseparable part.