Paul Verhoeven Questions the Very Nature of Belief in ‘Benedetta’

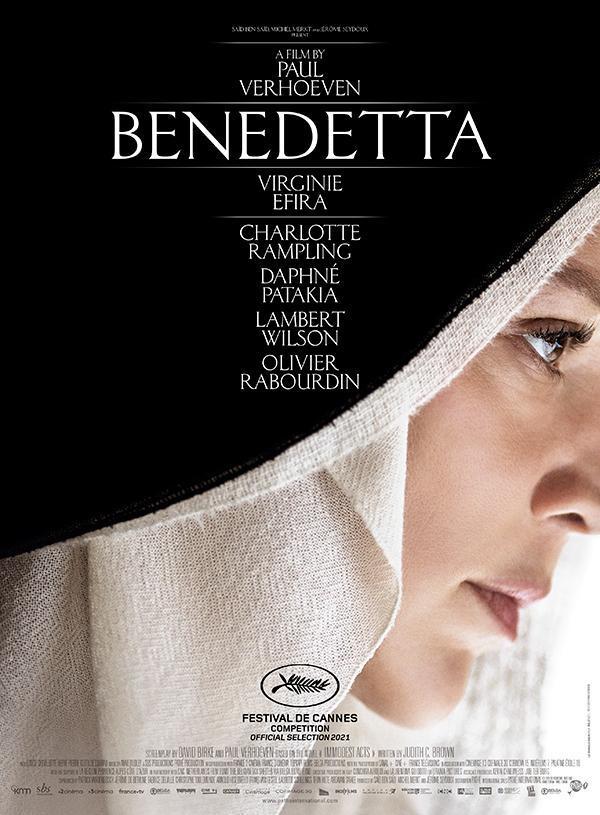

Dutch director Paul Verhoeven, known for legendary blockbusters such as RoboCop, Showgirls and Basic Instinct, is back with Benedetta, a film inspired by the true story of a 17th-century nun, mystic and lesbian. Benedetta was presented in the official competition at the Cannes Film Festival.

It only takes a few images of Benedetta, in competition at the Cannes Film Festival 2021, to know that we are in a Paul Verhoeven film. A fast-paced story, with little concern for subtlety or psychology, and a pronounced taste for sex and violence; the same ingredients that have earned this “violent Dutchman” a reputation as a sultry filmmaker.

Paul Verhoeven and Belgian lead actress Virginie Efira

Paul Verhoeven and Belgian lead actress Virginie Efira© Pathé

This is Paul Verhoeven’s second French film, after Elle (2016), starring Isabelle Huppert, which has already been presented at the Cannes Film Festival. Originally, Benedetta was supposed to be released two years ago, but the director’s health problems prevented its completion. Last year, due to the health crisis, the producer and distributor preferred to wait another year instead of releasing the film on the sly.

The story of Benedetta, based on true events, is that of a nun in early 17th century Italy, Benedetta Carlini lives a homosexual relationship in her convent, while proclaiming that without her the entire population of the town of Pescia would perish from the plague.

This is not the first time that Verhoeven has sought cinematic inspiration in history. We remember his fresco The Flesh and the Blood (1985) with the late Rutger Hauer, already set in Italy – although shot in Spain. That film was loosely based on the great book by the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga Autumntide of the Middle Ages (1919), which describes the difficult transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, a period of deep crisis marked by pessimism and violence. Verhoeven, and his regular scriptwriter of the time Gerard Soeteman, had translated this atmosphere into an extremely dark story without any empathetic or sympathetic characters.

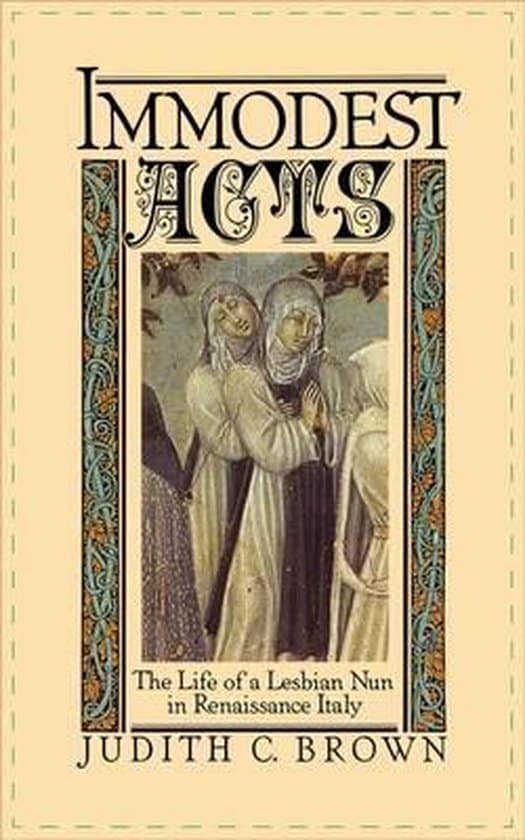

'Benedetta' is based on the nonfiction book 'Immodest Acts'

'Benedetta' is based on the nonfiction book 'Immodest Acts'For Benedetta, the same Soeteman had passed on a book by the American historian Judith C. Brown, Immodest Acts. The life of a lesbian nun in Renaissance Italy

(1987), but the director finally chose the American David Birke, already screenwriter of Elle, for the adaptation.

Brown’s book has been criticised by several historians because the notion of ‘lesbian’ is an anachronism for the time. Benedetta was seen as a “possessed nun” or “a deceitful mystic”. For others, however, Judith Brown’s study was a precursor in the rediscovery of the history of women and sexuality. In any case, it seems clear that Benedetta’s transgressive and iconoclastic behaviour fascinated Verhoeven. Benedetta’s life is indeed a sign of a deep crisis in the Catholic Church, unable to find an answer to the plague in Italy.

Verhoeven questions in the film the very nature of belief, a subject that has preoccupied the director all his life

But to reduce the film to a simple indictment of the Church, as several French critics have done, would be to do injustice to Verhoeven’s approach. He is a provocateur, certainly, he has no respect for the Catholic Church, but his real purpose with this film is much more complex. Firstly, because Benedetta herself is an ambiguous, even disturbing character. She is manipulative and mysterious like Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct (1992), or like Renée Soutendijk in The Fourth Man (1983). Verhoeven, author of a book on the historical figure of Jesus – a book he has promised to adapt for the cinema – questions in the film the very nature of belief, a subject that has preoccupied the director all his life. Now an agnostic, he has had a mystical experience, a theme that we find in his absolute masterpiece Spetters (1981).

© Pathé

In the structure of Benedetta, this complexity and ambiguity is reflected in several twists and turns that leave the viewer wondering, wavering and lost, while remaining glued to his seat. Benedetta is funny, serious, mocking and terrible all at the same time. At 82 years of age, Paul Verhoeven has lost none of his bite; he disturbs, even shocks, but makes us think, while showing, once again, the full possession of his means as a filmmaker.

In short, in order to approach this film – to which we do not claim to give the key, if it exists – it is essential to place it in the lineage of an abundant and polysemous work, fundamentally marked by the theme of human ambiguity.

The Cinémathèque française in Paris is currently devoting a major retrospective to Paul Verhoeven, until 1 August.