Tessa Leuwsha’s ‘Plantage Wildlust’ Translated into English

In February and March of this year, students from two British Universities, UCL and the University of Sheffield, embarked on a collaborative project to translate an excerpt from Plantage Wildlust (Plantation Wildlust), the fourth and most recent novel of the Surinamese Dutch writer Tessa Leuwsha. You can read the translation of this story about the harsh life on a coffee plantation here for the first time, with an introduction by a student.

The novel, set in Suriname’s capital Paramaribo in the early twentieth century, is wonderfully atmospheric. Leuwsha depicts with subtlety how societal tensions played out between individuals at a time when power structures were being re-negotiated, following the abolition of slavery and the arrival of indentured workers; a period that has previously received little attention, says Leuwsha.

Plantage Wildlust is character-driven, focusing on the nature of the individual and challenging preconceptions about group identity at the time. “I thought: is it possible that you can be a victim but also be a perpetrator at the same time?” the Amsterdam-born author explained to us via video link from her home in Suriname.

It was the historical knowledge and sensitivity for the social context required to do justice to these complex individuals and character relations that posed the biggest translation challenge. Yet, what was, for many of us, a first encounter with literary translation was made far less daunting thanks to the invaluable support and advice of literary translator Jonathan Reeder. He was on hand to answer questions and offer guidance, even sharing his view on the role of the translator. Inevitably, the project wasn’t just about creating a translation. It is also the legacy of the colonial past, the responsibilities of the translator, and the significance of translation as a political intervention.

With thanks to the Dutch Language Union, Dutch Foundation for Literature and the Dutch Departments at UCL and the University of Sheffield for their support, without which the project wouldn’t have been possible.

Megan Strutt (University of Sheffield)

Editorial team: Jonathan Reeder, Jake McGill, Anna Milhic, Nicole Oshisanwo

Translators: Nathanael Fogbel, Alice Garside, Clara Guislain, Leo Harrison, Robert Heaney, Thomas Macaulay, Jake Mcgill, Anna Mihlic, Nicole Oshisanwo, Matthew Rate, Lara Rendl, Lukas Shakesheff, Elinor Sheridan, Megan Strutt, Chloe Thompson, Georgia Thompson, Maayke Vlas, Abigail Woods

Project Coordinators: Henriette Louwerse, Christine Sas

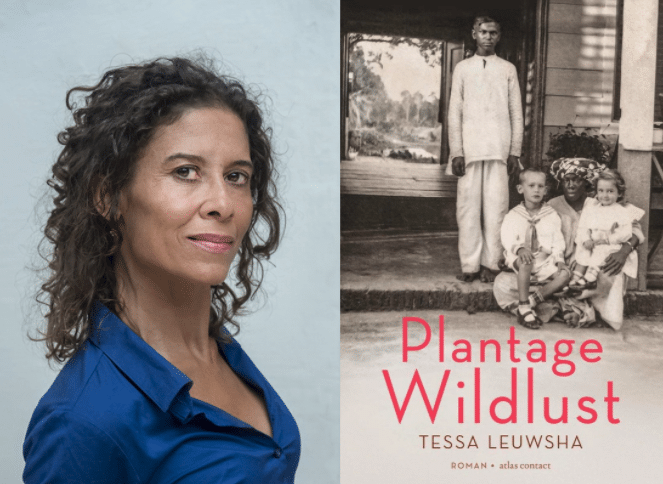

Tessa Leuwsha

Tessa Leuwsha© Sirano Zalman

Plantation Wildlust

Exactly a month after his last visit to the gentlemen’s club, Oscar was making his way back again, when a tall black man caught his eye. He was standing by the riverbank, not far from the building. He was wearing a floppy brimmed hat and was skimming stones across the water, something Oscar hadn’t done since he was a boy. He stopped to look at the man. Wouldn’t a day off be nice… Oscar pictured himself standing there, felt the cool sensation of the stones resting in his hand and heard their soft splashes. He walked on, entered the club, and took a seat at the bar.

It was rather early, so there were only a few people and he knew none of them. The bartender was nowhere to be seen. From his stool, Oscar gazed at the river. Somewhere further south of the bend lay Wildlust. He was uneasy at the thought that he was responsible for that piece of land and the people.

He was thirsty and rapped his knuckles on the counter. At that moment, to his surprise, the man he had noticed earlier by the water entered. He opened the swing-door at the side of the bar and stood behind it. He must have only been employed there within the last month.

“Sorry, I was just taking a short break”, said the man. “What can I get you?” Oscar ordered a drink and observed him curiously.

“I’m Brouwer” he said, “director of Wildlust”.

“Rudolf Bonaparte, pleased to meet you,” said the new bartender and he placed Oscar’s glass in front of him. Oscar found that his gestures exuded a certain calm. Others, upon seeing his white complexion, would adopt an air of eager servility which made him uncomfortable. This man clearly couldn’t care less.

Oscar slid his stool closer. “A fine name. I haven’t seen you here before, how did you end up here?” Rudolf glanced around. The club was still quite empty. He ran a cloth over the counter and said “I come from a plantation, my family are part-owners”. Oscar sat up and nodded encouragingly, intrigued by his story.

Plantation De Goede Hoop lay on a cool creek, a day’s trip away from Paramaribo, Rudolf said. It was a densely wooded area. During slavery, the cocoa plantation had known one owner after another, the last of whom was a young man from Twente who had invested his father’s money in a piece of land in Suriname. The man was also the owner of Rudolf’s grandparents, at a time when abolitionists were already demanding an end to slavery. Every enslaved person eagerly awaited that day and since it never seemed to come, Rudolf’s grandfather, who was highly regarded by the other slaves, encouraged them to resist.

Soon after, the farm tools, such as the hoes and the pickaxes, started disappearing. When the owner confronted Rudolf’s grandfather about it, he kept a straight face and the rest followed suit. After that, the slaves themselves began to disappear too. They left in the middle of the night, alone or in groups, with what seeds and grain they could carry. Sometimes the hounds across the creek picked up on their scent, foaming and panting from excitement until they were able to seize an ankle or a calf and the slave fell screaming to the ground. But there were also dark shadows who managed to escape that fate and disappear into the woods.

The man from Twente had not accounted for runaways in his ledger, let alone the rather sudden abolition of slavery, which had knocked the foundation from under his plantation: without free labour, De Goede Hoop was practically bankrupted overnight. The owner was entitled to compensation for the freed slaves but the money soon ran out. He also had to give the new citizens a surname, just Grietje or Hendrik no longer sufficed. He gave them the most fantastical names: King, Nomansgrief, Stumblingblock and, to their leader, Bonaparte. Good luck with that! And when eight of them, including this Bonaparte, had the audacity to make a bid for his land with money scraped together from the income from their allotments, the Twentenaar didn’t hesitate for a moment. He left the colony in a hurry as soon as the sale was closed.

Even before emancipation, missionaries – white men in white dresses – had built a simple schoolhouse along the creek. They had also built a small church next door which, like the school, was painted white with a red roof. The church was always full and the people listened quietly, because members of the congregation were crucial buyers of the plantation’s products. Rudolf’s parents sometimes had him place a bottle of liquor and fresh flowers at the edge of the forest for the Winti gods. The other plantation residents also offered similar beverages; deaf to the diatribes of the minister who warned against such unholy practices on Sundays.

One day the minister appeared at Rudolf’s house. “Go outside and play,” his mother told his brothers; only Rudolf could stay inside. The minister would soon be leaving for the city, he said, did Sir and Madam not want to send their son along with him? The boy was bright. His talents risked being wasted on the plantation. He could even become a minister himself.

Rudolf’s parents had looked at each other questioningly. They were barely literate themselves. “There is no future for our son on the plantation,” Rudolf’s father decided, while his wife stared at her feet. Nobody had asked Rudolf what he wanted.

In Paramaribo he struggled to settle into his new rhythm. Whilst he had his own room in the rectory, a modest space with a cross above the door, he missed the pleasant bustle of his brothers. And he missed being outdoors. His days were subject to a strict schedule: prayers, three meals a day, tidying up around the church. However, as he reached adolescence, the pulpit didn’t shine as brightly as it should have. When the pastor confronted him about it, Rudolf shrugged. It didn’t bother him. The situation had become untenable. Returning to the plantation was out of the question, he could already see his parents’ disappointed faces. One of the parishioners had come to his aid, offering him a place to stay and arranging some work for him at the gentlemen’s club. Rudolf seized the opportunity even though he didn’t want to stay here long. The city stifled him, he said.

A few members entered the club and Rudolf stopped talking. The men greeted Oscar, ordered and found their way to one of the small tables. While Rudolf poured the drinks, Oscar suddenly realised that although Creebsburg had thorough knowledge of the business and, in his own despicable way, ruled with an iron fist, someone ought to counterbalance him. Oscar didn’t necessarily have to do that himself.

“I could use someone like you,” he said. “Pay me a visit if you’re interested.” Rudolf nodded absently, busy with the order. Oscar slid off the bar stool and went to join the group. During the conversation, his eyes kept drifting towards Rudolf, as if the barman represented a solution that Oscar himself had yet to fully grasp.

When Rudolf arrived that day, Oscar recognised him from afar. He wore the same hat and sat upright with his long upper body between baskets and boxes on the deck of the riverboat that was heading for the plantation. These days it was Oscar who kept an eye on the field, but he could no longer bear Creebsburg’s presence. The overseer had yet again walked a few steps ahead of him with the boy in tow, as if he were in charge.

“The supply boat’s arrived, I’m going to go and check on it,” he called to Creebsburg, who nodded over his shoulder, uninterested. Only the boy paused for a moment, unsure who to obey, and then he scampered after the overseer. Oscar let out a deep sigh as he approached the jetty. He would have happily dismissed the guy then and there, but it wasn’t possible, for the next harvest was already looming.

The ferry docked. Rudolf deftly jumped onto the jetty and helped unload the sacks of flour and beans. Once the cargo was unloaded, he tipped his hat and bade farewell to the skipper, who immediately pushed back out into the water. He turned to the house, saw Oscar on the path and raised his hand. Oscar approached him somewhat suspiciously. He had no longer expected Rudolf, and now that he had arrived anyway, he began to have doubts. What could this man really do?

By now, it was nearing eleven o’clock and the sun was still rising. He held a hand above his eyes to shield them from the light. “You’re here,” he observed drily. Rudolf gave a slight nod and hoisted his kit bag higher on his shoulder. It soon dawned on Oscar that it was Creebsburg who normally took on new workers and that now, outside of the harvest season, they didn’t need extra hands.

“Have you got any experience as a stoker, as a machinist?”

Rudolf politely took off his hat. “That shouldn’t be a problem.”

A cloud slid in front of the sun. Oscar lowered his hand and narrowed his eyes somewhat suspiciously. “All right then,” he said.

“You can go,” he said to Duvalier the same day. It was break time and Creebsburg had retired to his house. The stoker looked at him in disbelief. Oscar held up a pouch of money. “Here, this should tide you over for a couple of months in Paramaribo.” Grateful, the European accepted the money. He quickly gathered his things, said his goodbyes and hurried to the jetty.

Oscar then gave Rudolf a tour of the factory and they had a look around the warehouse. The sacks of coffee had been transported to the city and were taken to Holland from there. The ground floor and the floor above were now empty, Oscar’s voice echoed through the space. They climbed the stairs. The bunks gave the attic the appearance of a field hospital, a place where fierce battle raged. Rags lay on some of the beds serving as sheets. Rambaroos’ hammock hung in the corner nearest to the river. Rudolf’s would hang at the back of the room. Oscar left him alone to settle in. As he left the warehouse the bell announced the end of breaktime.

The new mechanic promptly started his duties that afternoon. Oscar went to have a look around the factory. Rudolf was polishing the boiler and checking the mechanics of the bucket elevator. “Everything needs to be ready for the upcoming harvest,” said Oscar. An old sensation returned to him: grasping the handlebars of his bicycle, head in the wind. He missed that feeling.

At the lock he bumped into Creebsburg. The overseer peered down at the gate which was in need of replacement; the tired wood scored with deep cracks. Oscar also looked down. “I let Duvalier go,” he announced in passing. Out of the corner of his eye he saw Creebsburg stiffen. He then rummaged in the pocket of his dust coat, fingers automatically doing their job: picking, rolling, lighting. He inhaled deeply and then said, “If you say so.” Then cleared his throat and walked away.

One afternoon as the workers trudged to the kampung, Oscar made his rounds of the jetty and the various buildings. On occasion tools were left lying around, or there was not enough firewood. In that case he would have the mess cleaned up or more wood ordered. Just before six o’clock, he passed through the narrow passage between the coffee works and the small building next to it, where, in better times, cocoa was processed. The path ended by the river, and the sun sat low above the water. Backlit by the sun, Oscar recognised the tall stature of the stoker and he walked down the path. He had only taken a look behind the works once before.

On the narrow bank, broken crates were stacked up against the building and the rusty piece of guttering that Oscar had removed also laid there. Rudolf sat on a crate that he had placed near the water and strung a piece of bread on a hook; the line attached to a bamboo fishing rod. He nodded to Oscar, seemingly unsurprised to see the director, and cast his line.

“Keep your distance from the locals,” Boomsma had advised Oscar in a hushed tone during one of their meetings at the club. “They can’t be trusted.”

Oscar folded his hands tightly behind his back. “Are the fish biting?” he asked. “A bit,” Rudolf replied curtly. He observed Oscar for a moment, then offered him his fishing rod. “Here, try for yourself.” Surprised, Oscar accepted his offer. Rudolf also offered him his crate and took a rickety one from the stack. A short distance from the director, Rudolf set himself up again, the line and hook tied to another bamboo stick. Each lost in their own thoughts, they stared at the water, onto which the sun cast its last golden glow.

Bubbles soon floated up around Oscar’s bait and the piece of bread dipped under the water. With an enthusiastic flick he pulled up his fishing rod. The line dangled wildly, splashes erupting from the surface, but nothing hung on it. Slightly disappointed, Oscar slid the bucket, within which Rudolf kept his fishing tackle, towards himself for a new piece of bait. At that same moment, Rudolf’s bamboo stick bent sharply. Oscar forgot what he was doing and shouted: “Pull it up!” The stoker quickly pulled up his stick and a huge fish floundered on the hook. Scaly and shiny, its gills twitched. The men grinned at each other and crouched over the catch together. Rudolf reached into the bucket, and with a rusty knife cut the gills in a single movement. The sun was now setting and the golden glow from only moments before became into a dim twilight. The euphoric moment was gone. Water trickled from the mouth of the dying fish like drool. Rudolf cut open its stomach, the intestines spilled out and the metallic smell of blood filled the air. Oscar shuddered. He imagined himself lying there, dead, soon to be skinned. In his head, he heard Boomsma, “they can’t be trusted.” The voice of the Company representative also echoed in his mind, businesslike and nasal, “what skills do you have for this task?” Rudolf would never have understood, but Oscar wanted to throw the fish back into the river, to grant it a second chance at life. Would a real man do that?

He straightened his back and looked down at the stoker, who was still kneeling. He was on a round of inspections, Oscar reminded himself. “Clean all this up later,” he said sternly. Rudolf’s hands froze. He tilted his head slightly, surprised. Oscar tried, with all his might, to ignore the stab of regret.

He left the man alone. The passage was now a narrow, dark alley. At the end, he saw the shed on the right, closed, the only rays of light shining through the cracks in the attic shutters. In his own house, the lights came on one by one. Janna lit the lamps at seven o’clock sharp. He headed for the director’s residence like a boat to a lighthouse.

Photos of the Peperpot coffee plantation in Suriname, on which ‘Plantage Wildlust’ is based

A typical 'kampong' house, where the plantation workers lived.

A typical 'kampong' house, where the plantation workers lived.© Janssen family archive

The proud plantation director next to a servant of the steam boiler.

The proud plantation director next to a servant of the steam boiler.© Janssen family archive

A wooden jetty at the plantation

A wooden jetty at the plantation© Janssen family archive