Polydore De Keyser, the Flemish Hotelier Who Became Lord Mayor of London

Polydore De Keyser was Lord Mayor of London from 1887 to 1888, a position that made him a celebrity in Britain and in his native Belgium. At the end of his year in office, he was knighted by Queen Victoria, and the town of Aalst introduced a Polydoor family of giants into its carnival parade, although this was rather a backhanded compliment.

Born in Dendermonde in 1832, De Keyser came to London as a child and was educated in England, Germany and Belgium. He was initially destined to become a surgeon, like his maternal grandfather, Dr Charles Troch of Dendermonde, but the death of his elder brother Emile in 1850 meant he had to join the family hotel business instead.

Just why his father, Constant De Keyser of Ghent, came to London and how he got into the hotel trade is hard to pin down. But the business involved frequent brushes with the law, and from 1846 onwards his name appears in the press connected with disturbances, thefts and other mishaps at the Royal Hotel, Blackfriars. From these court reports, we learn that De Keyser had kept the hotel since 1843, and that at some point he had been a merchant and stockbroker in Brussels.

An 1891 brochure for De Keyser’s Royal Hotel

An 1891 brochure for De Keyser’s Royal HotelNew York Public Library

Whether he established the Royal Hotel himself or took over the business is also unclear. The hotel initially occupied one or two houses on Chatham Place, where Blackfriars Bridge joined the north bank of the Thames, and it expanded over the years to occupy more of the street. Polydore became manager of the hotel in 1856, when his recently widowed father retired to Brussels. He inherited it in January 1861, and a year later married Louise Piéron, the daughter of a Brussels hotel owner.

De Keyser’s Royal Hotel was the biggest hotel in London

By this time De Keyser’s Royal Hotel, or simply De Keyser’s Hotel, had become a firm favourite with European visitors to London. While its location was not particularly fashionable, it had the romance of being close to the river, and offered a continental style of service. The business grew to such an extent that De Keyser had to build a new hotel next door.

Opened in 1874, its facade wrapped around the corner of Bridge Street and into the recently completed Victoria Embankment, presenting an elegant curve to the river. According to a report in The Hour, the new hotel combined “British solidity and comfort with Parisian lightness and elegance”. The addition of an extension on Chatham Place, replacing the old hotel buildings, made De Keyser’s the biggest hotel in London. It had rooms for 480 guests, dining rooms capable of holding 650 people, recreation rooms, and accommodation for 150 staff.

A postcard of De Keyser's Royal Hotel, from around 1900

A postcard of De Keyser's Royal Hotel, from around 1900© Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, De Keyser was also building a reputation in London’s civic life. In 1868 he was elected to the council that governs the City of London, which is say the historic centre of London rather than the whole metropolis. He gave generously to charities, and helped in their organisation, including a fund for destitute Belgians in Britain. He was a hospital governor, a patron of the Guildhall School of Music, and a member of the Society of Arts and the Royal Geographical Society. The list just goes on.

De Keyser at the time of his election as alderman, from The Illustrated London News

De Keyser at the time of his election as alderman, from The Illustrated London NewsIn 1882 he was elected alderman for Farringdon Without, one of the 25 wards that make up the City of London. Each alderman could be Lord Mayor of London once, holding office for just one year, so it was already probable that De Keyser would be mayor at some point in the future. This would make him the first Roman Catholic to hold the position since the Reformation, a prospect that already raised hackles in the press. “The Channel Tunnel will be a source of danger when De Keyser is mayor,” wrote The Referee, a Sunday paper usually more interested in sport. “We shall wake up one fine morning to find the Pope at the Mansion House, and the Lord Mayor handing over the keys of the City to him in the presence of an army of pilgrim soldiers, arrived from foreign parts during the night.”

De Keyser would be the first Roman Catholic to hold the position of Lord Mayor of London since the Reformation

His election as alderman was challenged, not on the grounds of religion but because he was foreign-born and held a license to sell alcohol. This second charge was not a moral judgement but a potential conflict of interest, since the City controlled the licenses. But both objections were dismissed. De Keyser had been naturalised a British subject in the 1850s, and said he would not get involved in issuing alcohol licenses. His supporters also pointed out that, as well as being a Catholic, he was a Freemason of long-standing, which if nothing else indicated certain flexibility in belief.

Polydore De Keyser in his mayoral robes

Polydore De Keyser in his mayoral robes© Wikimedia Commons

The same objections about De Keyser’s birth and religion returned when he became a mayoral candidate in 1887. Questioned in front of the ‘liverymen’ who made the selection, De Keyser replied that, in his official capacity he recognised only the established Church of England, but that in matters of charity, philanthropy, and education he recognised all religions in which God reigned supreme. The answer provoked cheers in the crowd, and he was duly elected.

This made him a national figure, worthy of description in the press. “He is a tall, well-proportioned, elderly man,” wrote the London correspondent of the Liverpool Daily Post. “He has a well-grown beard, whiskers, and moustache of a dark-brown hue, but his hair is already besprinkled with grey. He speaks English very fluently, but his voice is very high pitched, and his accent betrays the foreigner.” Several papers reprinted a long account of a visit to his opulent house in Clapham.

Liverpool Daily Post: "He speaks English very fluently, but his voice is very high pitched, and his accent betrays the foreigner."

Belgium was also quick to take an interest in its now-famous son. The press covered his investiture in great detail, noting the prominent role played by the mayors of Brussels, Dendermonde and Liège. As the parade marking the occasion passed De Keyser’s Hotel, one account noted, the mayor was visibly moved by hearing the Belgian national anthem. In May the following year, De Keyser entertained a delegation of more than 60 Belgian mayors and other civic officials at his hotel, with a banquet in their honour at the Lord Mayor’s official residence.

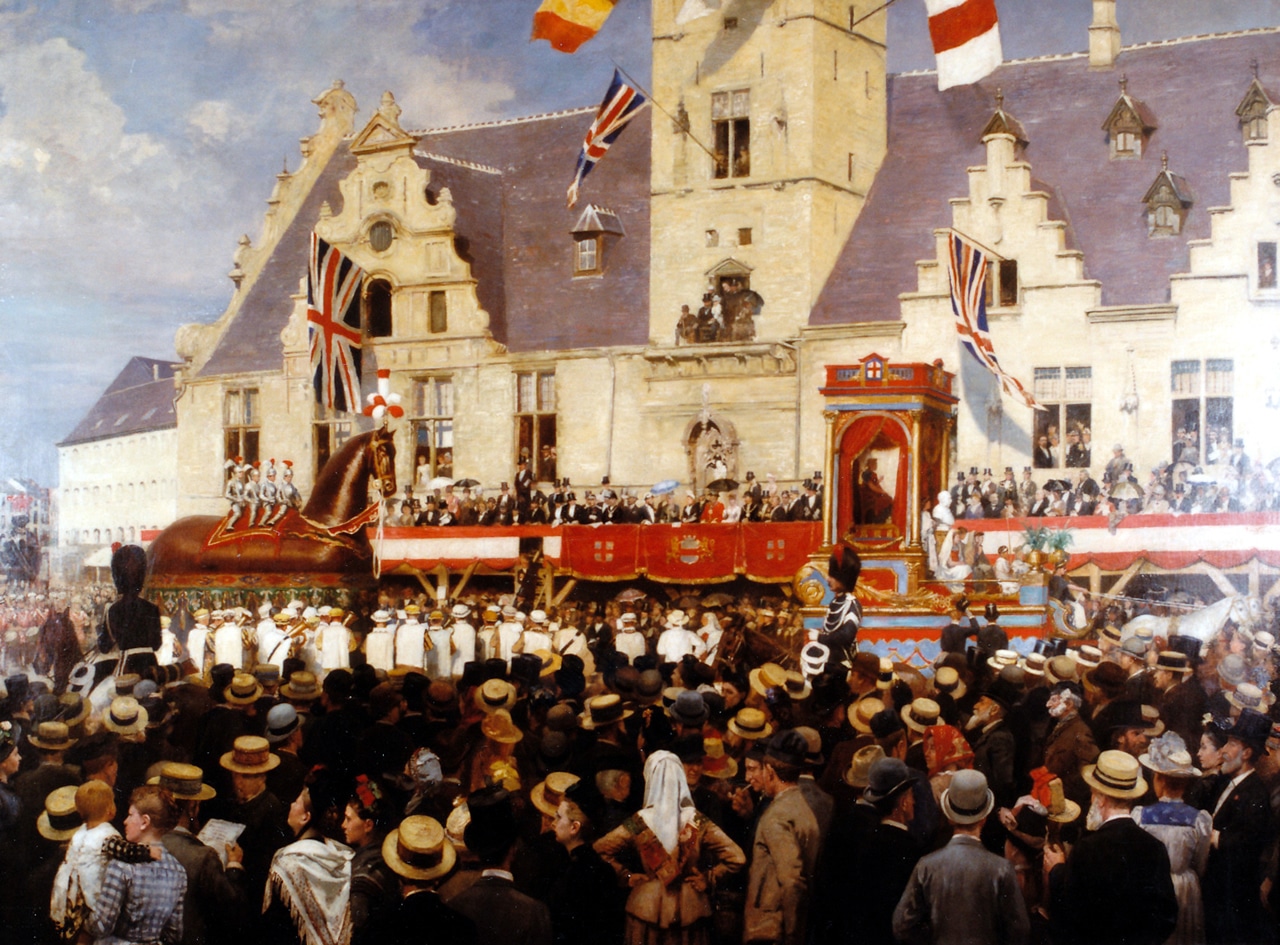

Polydore De Keyser’s visit to Dendermonde, recorded in an 1891 painting by Jan Verhas.

Polydore De Keyser’s visit to Dendermonde, recorded in an 1891 painting by Jan Verhas.© Wikimedia Commons

De Keyser was equally feted when he visited Belgium. In August 1888 he visited Dendermonde, which put on a lavish celebration in his honour. He addressed the crowd in Flemish and French, and the next day visited the town and the house where he was born. The fuss so annoyed rival city Aalst that it created a family of giants in his ‘honour’ for the next year’s carnival parade. Polydoor, Polydora and baby Polydoorken remained part of the city’s repertoire for years to come. The British press was also puzzled by the attention lavished on De Keyser, observing that the Belgians had clearly misunderstood the Lord Mayor’s modest powers.

The Aalst giants Polydoorken, Polydora and Polydoor, seen here with the city’s own Ros Beiaard.

The Aalst giants Polydoorken, Polydora and Polydoor, seen here with the city’s own Ros Beiaard.© Stedelijke Musea Dendermonde/Facebook

While clearly a consummate politician, De Keyser did occasionally express himself too freely. In a lengthy interview with L’Indépendance Belge about Jack the Ripper, then at large in London, the mayor said the neighbourhoods where the crimes took place were beyond all help, their inhabitants poor by choice and idle by profession. These unexpectedly harsh comments were repeated in the British press. An even more impressive row broke out when he refused to let a city meeting hall be used for a discussion on national defence, saying its backers were fomenting unpatriotic agitation. “Who is he to judge of what is or is not ‘unpatriotic’ in England?” fumed the St James’s Gazette.

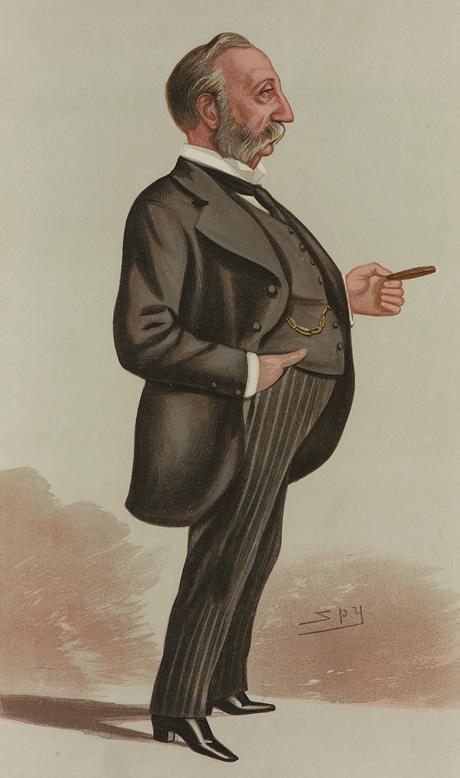

Polydore De Keyser, from Vanity Fair, 1887

Polydore De Keyser, from Vanity Fair, 1887© Vanity Fair

Yet when it came to his real constituency, the businessmen of London, his instinct was strong. When the government refused to support a British section at the Paris Exhibition of 1889, it was De Keyser who stepped in to organise a delegation of British companies. For this and other services, he was knighted at the end of his term as mayor. After that, Sir Polydore continued to be active in public life until deafness forced him to resign as an alderman in 1892. In 1897 he transferred his personal ownership of De Keyser’s Hotel to a limited company, and its management to Polydore Weichand de Keyser, the son of his youngest sister, Emma. Increasingly unwell, he died in London in January 1898.

The Polydoor Giants symbolised the rivalry between Aalst and Dendermonde.

The Polydoor Giants symbolised the rivalry between Aalst and Dendermonde.© AjoinPedia

The Polydoor giants continued to appear in the Aalst carnival until 1914, after which they seem to have disappeared. The First World War also spelt the end of De Keyser’s Hotel. Continental visitors declined dramatically, and by 1915 it was essentially bankrupt. The following year, the building was requisitioned to house the Royal Flying Corps. After the war, it was acquired by chemicals company Lever Brothers, and knocked down in 1930 to make way for the new Unilever headquarters, which still stands on the spot. While De Keyser is scarcely remembered in London, Aalst’s memory (and its rivalry with Dendermonde) proved more resilient. In 1957, new versions of Polydoor and Polydora were made for the carnival. They paraded through the town until 1976.