PRE-PUBLICATION LEOPOLD’S LEGACY – Belgium’s Enduring Imprint of Empire

In his artistic practice photographer Oliver Leu (b. 1976) is concerned with questioning religion, the construction of history, the abuse of power and the consequences of colonial pasts. Since 2014 he has developed these ideas in his project on Leopold II, for which he is researching and photographing the various forms of representation of the colonial history of Congo in Belgium.

In his book Leopold’s Legacy, out soon, Oliver Leu presents an eclectic collection of visual research, focusing on various topics from colonial monuments and prestigious architecture to antique postcards and collaged sculptures for alternative monuments. ‘Now six decades removed in time from the Congo’s independence, Belgium’s imperialist inheritance in bronze, stone, and other visual forms continues to weigh upon the country,’ states Professor of History, Matthew G. Stanard, in the introductory text, ‘it is a visible and enduring legacy of Europe’s last age of empire.’

Belgium’s Enduring Imprint of Empire

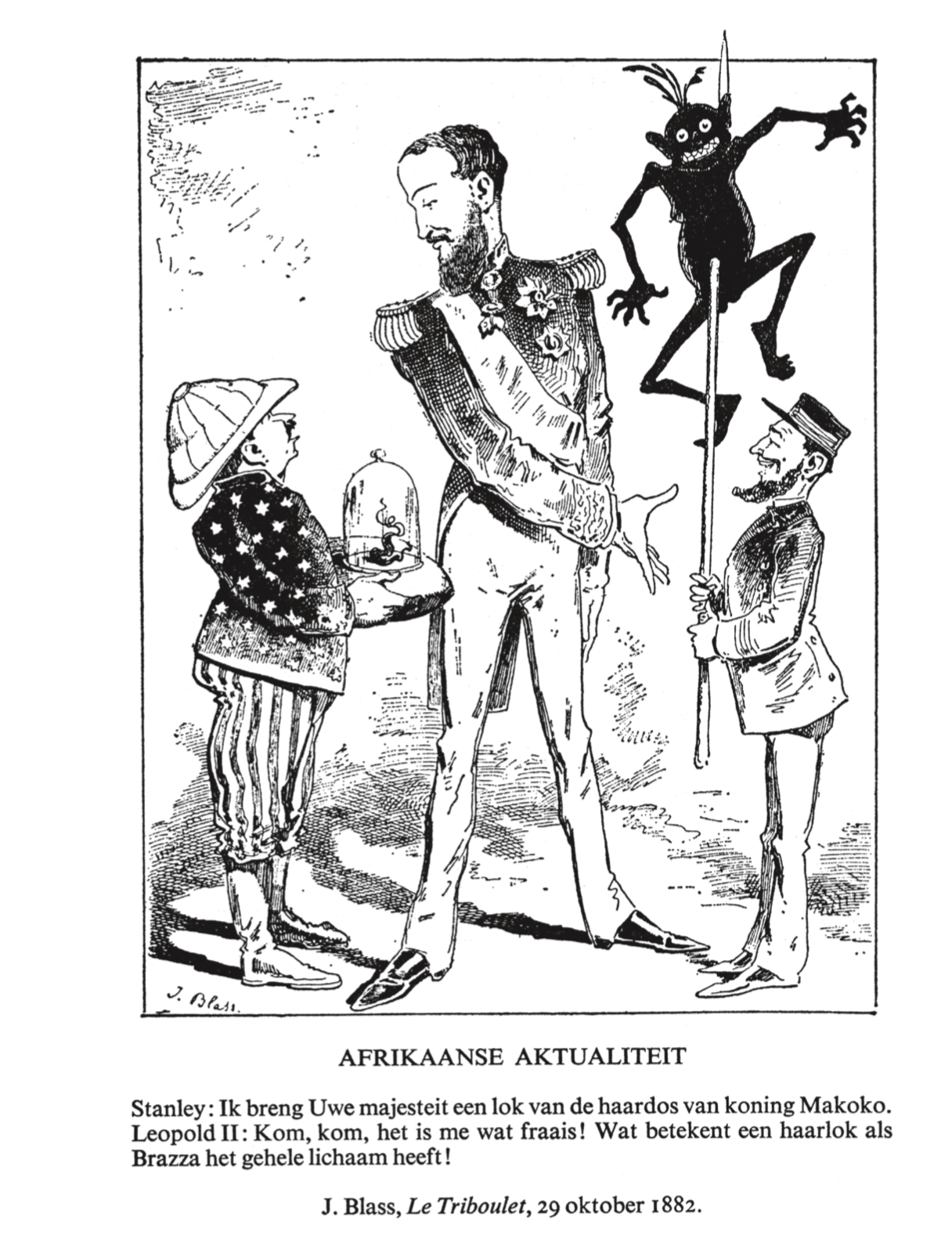

Leopold II spearheaded Belgium’s colonial rule in central Africa. A tall king with big ambitions, Leopold felt trapped inside his small, constitutional monarchy. Even before he ascended the throne in 1865, he dreamed of acquiring an overseas colony, and once king — and faced with Belgians’ decidedly un-imperialistic ambitions — he plotted to get one on his own. By underwriting voyages of exploration, hosting a Brussels Geographical Conference in 1876, creating front organizations, and hiring explorers including Henry Morton Stanley, by the early 1880s Leopold had emerged as a leading figure (albeit behind the scenes) in European claim-making in central Africa during a time of intensifying foreign activity there. In the mid-1880s, he parlayed this involvement into an assertion of control over the Congo River basin area, which was affirmed by the major European powers at the 1884–85 Berlin Conference.

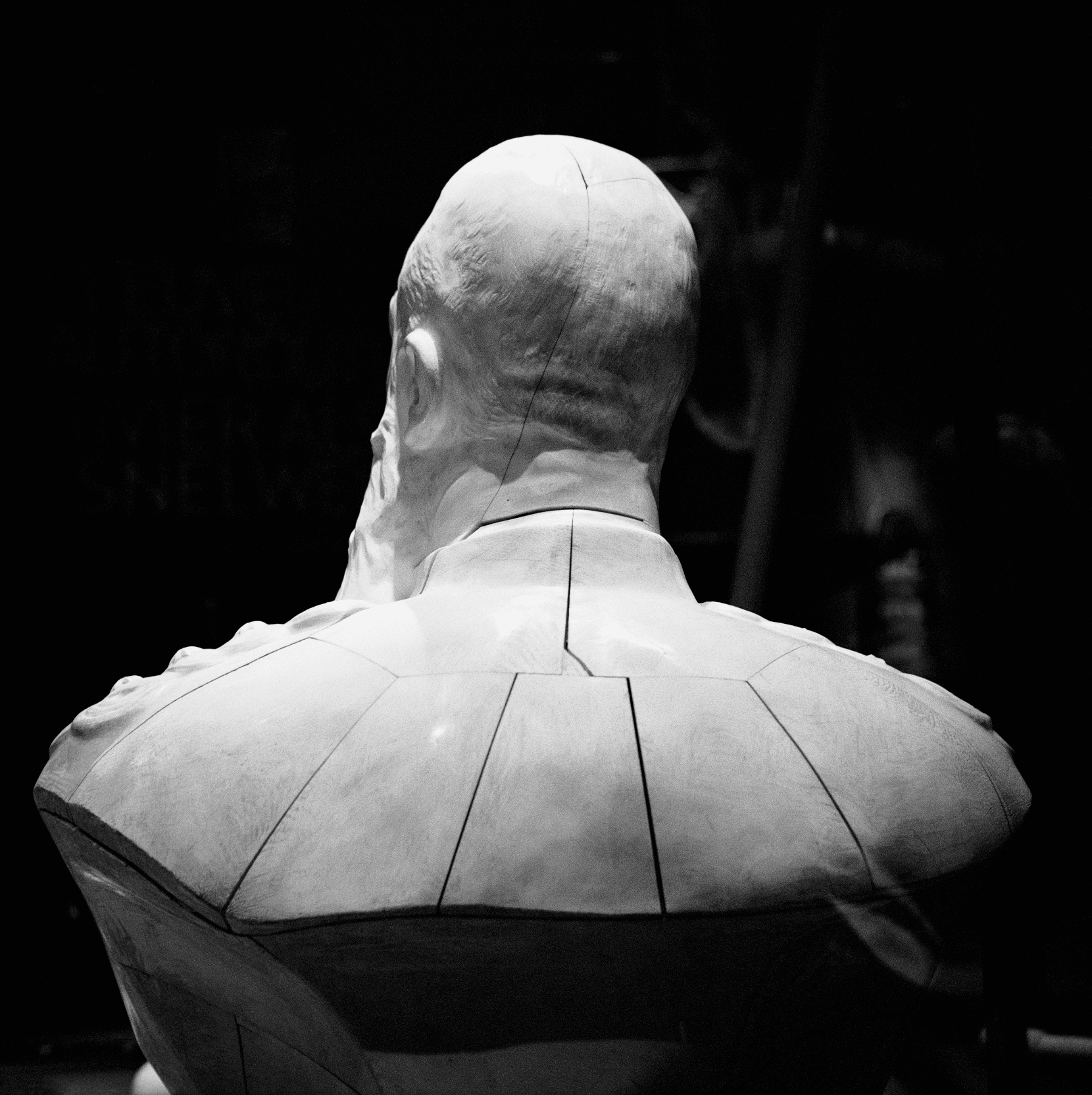

Bust of king Leopold II made from Congolese ivory

Bust of king Leopold II made from Congolese ivory© Oliver Leu, 2020

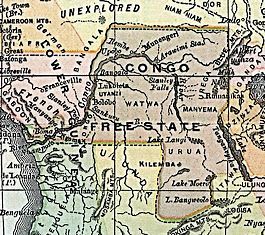

Leopold’s newly declared colony was baptized the Congo Free State (CFS), although it was ‘free’ only in the sense that it was not controlled by any European country. Instead, Leopold ruled the territories of the Congo by means of the CFS, a colonial state of his own design and legally distinct from Belgium — he became the roi-souverain or ‘king sovereign’ of the Congo.

Eventually, the CFS reached a size nearly 80 times that of Belgium, but in 1885 Leopold II’s agents on the ground in central Africa controlled little of the vast territories he claimed. At the time one of the wealthiest people in Europe, the king exhausted his fortune underwriting the exploration, conquest, and occupation of the Congo. To recoup his expenses, and to turn the CFS into a profitable enterprise, his colonial rule sought maximum profit at minimum cost, which translated into forcing Congolese to extract resources for export, notably ivory and rubber. The horrific atrocities that resulted made Leopold II infamous.

Map of Congo Free State

Map of Congo Free StateBack home, the king attempted to transform Belgium into something greater through urban development. Major construction projects from early in the king’s reign included the covering of the Senne (begun 1867), the creation of the Jardin du Roi (1873), and the laying out of the Parc du Cinquantenaire (by 1880). These developments accelerated once ‘red rubber’ profits from the Congo began pouring into Leopold’s coffers toward the close of the century, funding the royal galleries in Ostend (1902–06), the Cinquantenaire Arch (1905), and the reconstruction of the Royal Palace (1904–10), among other projects.

After years of foreign condemnation of his colonial misrule — including the first international humanitarian campaign to harness photography to its cause — the roi-souverain ceded the Congo to his other kingdom, Belgium, in 1908. It was renamed the Belgian Congo, and the mining of ores formed the backbone of the colonial economy. This drastically changed not only the nature of the regime and its value as an overseas possession, but also its effects on Congolese and their reactions to colonial rule. This situation endured until Congolese achieved their independence in 1960, which meant the period of Belgian state rule was twice as long as the Leopoldian era.

For Belgians and Europeans, colonial imagery played a crucial role in shaping views of the Congo, Leopoldian rule, and colonialism in sub-Saharan Africa. These images were particularly influential because the Congo was never a colony of settlement and because so few Europeans ever travelled there. In 1908, there were only 2,939 whites in the Congo (including 1,722 Belgians); the numbers grew to some 100,000, but only in the very last years of colonial rule.

AFRICAN NEWS Stanley: "I present your majesty with a lock of King Makoko's hair." Leopold II: "How about that! What's a lock of hair when Brazza has the entire body!"

AFRICAN NEWS Stanley: "I present your majesty with a lock of King Makoko's hair." Leopold II: "How about that! What's a lock of hair when Brazza has the entire body!"J. Blass, Le Triboulet, October 29, 1882

Imagery of the CFS linked Leopoldian rule with violence more so than European colonial rule elsewhere, and from an early stage. Missionaries produced photos of forced labour, severed hands, and maimed children, while European and American political cartoonists skewered the king as a heartless profiteer. The international effort to end Leopold’s rule, led by the Congo Reform Association (CRA), circulated a trove of anti-Leopoldian images at lantern slideshows, in newspapers, and elsewhere. To refute the charges against him, Leopold II and his collaborators embarked on a counter-propaganda campaign that disseminated illustrations of advancements they had brought to Africa, such as missionary outposts, bridges, railways, steamships, and plantation agriculture. Although images of violence emerged from other colonial situations, such as Germany’s genocide against the Herero and Nama in Southwest Africa (1904–07), CFS abuses and the propaganda battle that resulted tended to multiply such imagery, transforming Leopold II into a notorious figure who pillaged a foreign land. This also provoked Belgian resentment toward any foreign meddling in their colonial affairs after 1908, and a fear that their legitimacy as colonial rulers had been enfeebled from the start. Such worries were especially troubling in a country without any upswell of imperialistic fervour. In short, imperial enthusiasts in Belgium produced wide-ranging pro-empire propaganda after 1908 to promote and legitimize their colonial regime both at home and abroad.

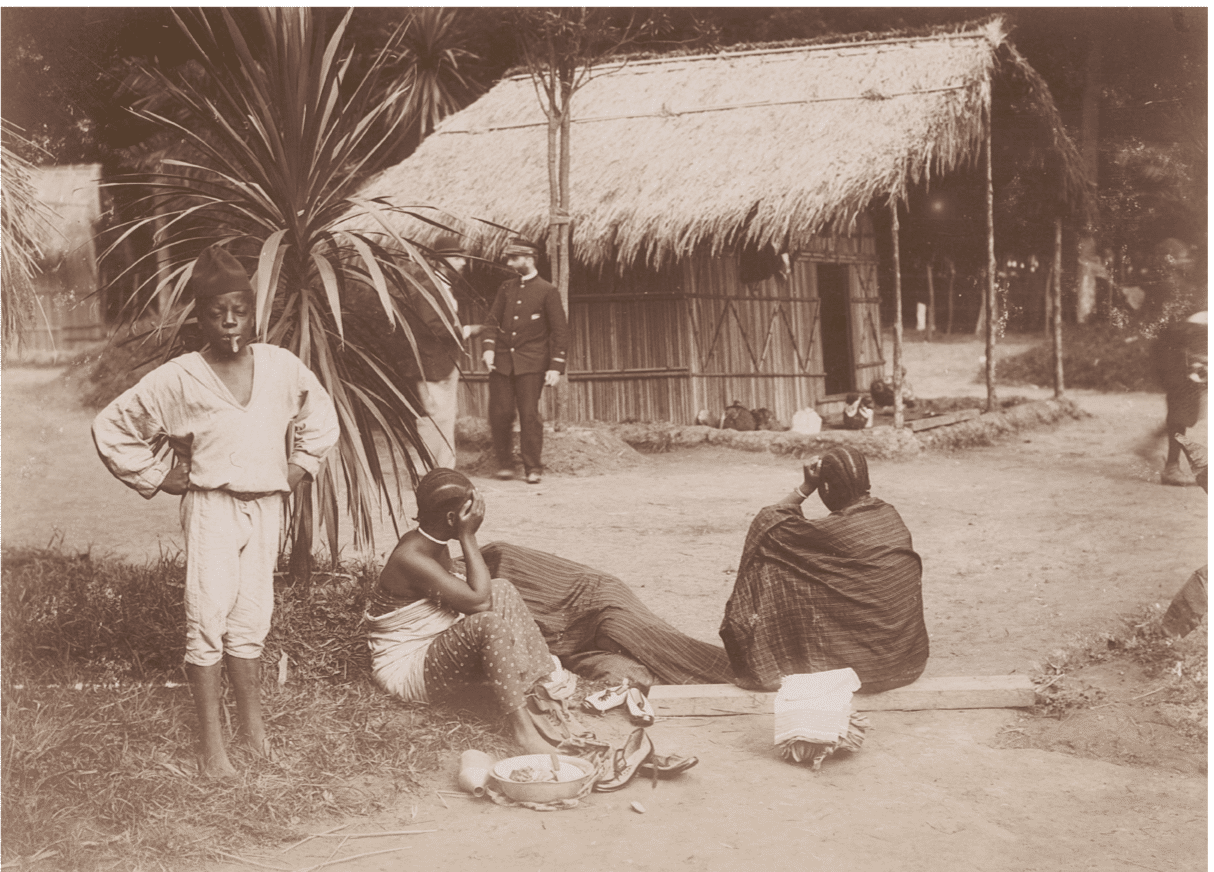

On the 1897 Brussels International Exposition 267 people from Africa lived in the Congolese village for the duration of the fair.

On the 1897 Brussels International Exposition 267 people from Africa lived in the Congolese village for the duration of the fair.© HP.1946.1058.1_SCAN_014, collection RMCA Tervuren; photo A. Gautier, 1897

Among the most remarkable displays of colonialism in Belgium between 1885 and 1908 were to be found at the country’s world’s fairs. Two expositions in Antwerp in 1885 and 1894 attracted 3.5 million and 3 to 5 million visitors, respectively, each boasting its own section coloniale. At the 1897 Exposition Internationale de Bruxelles, the Tervuren colonial section alone attracted between 1.2 and 1.8 million visitors. Displays at such events, including colonial pavilions, were dismantled at the fair’s end, but others endured, from the Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp, completed in time for the 1894 universal exposition, to photographs of Congolese ‘villages’ at the fairs that were disseminated on postcards, in books, and elsewhere. Such imagery, some of which circulated for decades, was crucial to forming a colonial imaginary because most Belgians never travelled to the Congo—just as Leopold II himself never once stepped foot in his African domain.

Equally, if not more important to the visual and monumental legacy of Leopold II and his colonial reign were images created after 1908. Belgium’s practice of hosting universal expositions continued: Brussels in 1910 (13 million visitors), Ghent three years later (9.5 million visits), Antwerp in 1930 (4,182,500 recorded visits to the Pavillon du Congo belge alone), and Brussels again in 1935 (20 million visitors). The final world’s fair hosted by Belgium, Expo ’58 (in Brussels), also included a major colonial section and recorded more than 41 million visitors.

Some 900 colonial films were created in central Africa before 1960, many of them propagandistic

Colonial imagery surfaced elsewhere during the period of state rule. Missie-expos were smaller-scale colonialist exhibits, often in missionary houses, that were used to attract visitors and raise monies to fund proselytizing efforts in the colony. The Congo found its way into advertising, temporary exhibits, celebrations like Antwerp’s 1909 koloniale feesten, and ephemera such as posters promoting the Koloniale Loterij. Both history textbooks and the country’s annual koloniale dagen sought to inculcate a colonialist spirit in the next generation. Colonial filmmaking took off in the 1930s; in all, some 900 colonial films were created in central Africa before 1960, many of them propagandistic. Museums were yet another venue, in particular the Museum of the Congo at Tervuren, a creation of Leopold II inaugurated in 1910 and emblazoned with the king’s double-L symbol. For decades, this vehicle of colonialist propaganda acted as the jumping-off point for most Belgians when it came to their initial encounter with Africa.

Activists modified the colonial monument in Ostend to ask for excuses for crimes commited in Congo

Activists modified the colonial monument in Ostend to ask for excuses for crimes commited in Congo© Oliver Leu, 2020

Imperialist monuments, another locus of imagery, date back to the very first years of the Leopoldian colonial endeavour. Hundreds of plaques, statues, busts, street names, and other commemorative markers were put up in Belgium to celebrate the African colony and to honour those who conquered it. Monuments strongly emphasized the military, in particular Belgian soldiers and officers who had served during the CFS period. After 1908, celebrating such men generated a kind of imperial tradition where none had existed, because unlike its fellow empire-builders, Belgium had no imperialistic past. Harkening back to the ‘heroic’ or ‘pioneer’ period of the CFS rooted the contemporaneous empire within a legitimate colonial history. Ironically, Leopold’s African rule, which was so horrific that international censure forced him to surrender it to Belgium, ended up becoming the foundational era upon which Belgians subsequently grounded the legitimacy of their colonial rule.

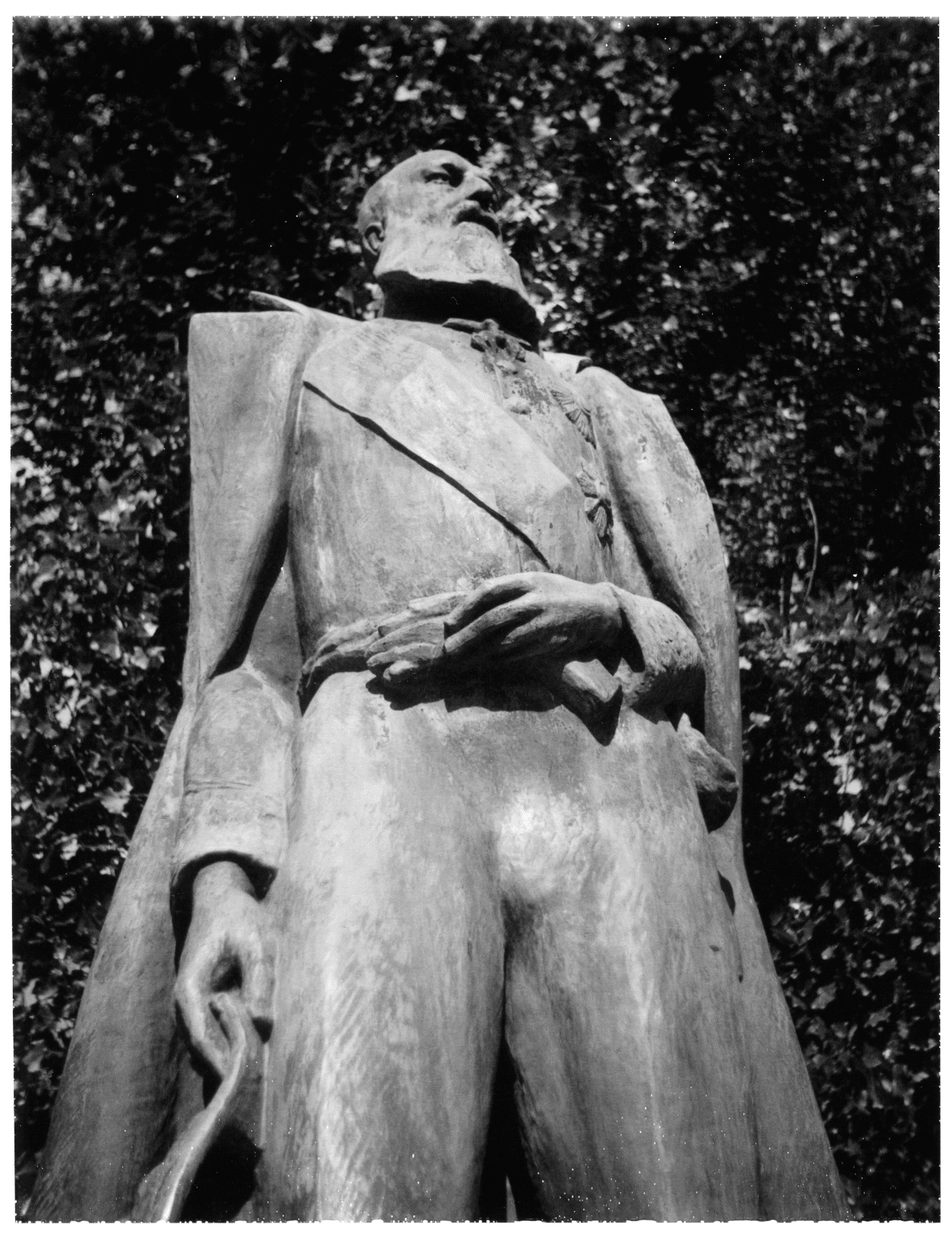

Monument to king Leopold II, Mons

Monument to king Leopold II, Mons© Oliver Leu, 2020

Pro-colonial monuments also contributed to the rehabilitation of Leopold II, helping him go ‘from worst to first.’ If at the time of his death in 1909 he was infamous abroad and little loved at home, by the 1950s, Belgians hailed him as a prescient colonial genius who had acquired a massive, resource-rich African territory for his home country. The post-1908 period literally recast the defunct monarch’s reputation. While only one monument was erected in the king’s honour before 1908 (in Ekeren, 1873), more than a dozen were unveiled in the decades following his death, six of them at the height of empire in the 1950s. These included Brussels (Place du Trône, 1926), Auderghem (1930), Ostend (1931), Arlon (1951), Hasselt (1953), Halle (1953), Ghent (1955), Forest (1957), Mons (1958), Namur (rebuilt in 1958), and Tervuren (1997). More than one — including the ensemble by Victor Demanet and Arthur Dupagne in Arlon — quoted the king’s own words in order to laud him as a forward-thinking, benevolent founder of empire: ‘I undertook the work of the Congo in the interest of civilization and for the good of Belgium.’ Now six decades removed in time from the Congo’s independence, Belgium’s imperialist inheritance in bronze, stone, and other visual forms continues to weigh upon the country, a visible and enduring legacy of Europe’s last age of empire.

Detail from the monument The Congo, I presume? by Tom Frantzen (1997), Tervuren

Detail from the monument The Congo, I presume? by Tom Frantzen (1997), Tervuren© Oliver Leu, 2020