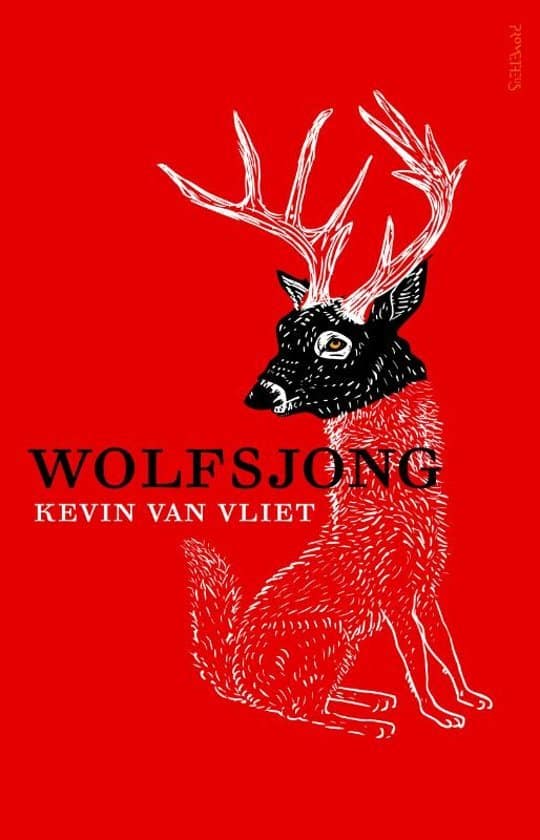

‘Wolfsjong’ by Kevin van Vliet: Prodigal Sons on a Quest for a Father

Wolfsjong (Wolf Cub), young Dutch author Kevin van Vliet’s debut novel, is a classic fable, a fairy-tale almost. This story, however, has an edge, a dark side, as all proper, thrilling fairy-tales should.

Kevin van Vliet

Kevin van Vliet© Bob Bronshoff

In times of lockdown and quarantine we can find comfort in reading the stories of hermits. People who, either voluntary or involuntary, withdraw from society, who have no difficulties with a lack of social interaction – on the contrary, in fact. They tend to be strong, somewhat mysterious men or women, scarred for life, blessed with the wisdom that comes with that, a wisdom their more socially-inclined fellow men sometimes lack.

The anonymous narrator in Wolfsjong by Kevin van Vliet (b. 1993) is extremely attracted to such a character. Oskar, a hermit from the village he grows up in, is an outcast. A man you mustn’t accept anything from, all parents implore their offspring. Just steer clear from him. A few days after his father’s funeral, the narrator, now a nineteen-year-old orphan, is left behind and feels the time is right to brush that piece of advice aside. ‘Oskar was my first true friend. Two weeks later, he was gone’, he tells us in the introduction, in his bone-dry style.

Many years after that meeting, the orphan recounts Oskar’s story. He is forced to do so without the help of letters, without pictures, without Facebook status updates. Instead, he is forced to rely on his memory, and we all know just how unreliable our memories can be. The orphan remembers Oskar telling him he descended from German nobility. However, he also recalls a few elements that might point to Oskar not telling him the whole truth. There were his meagre dwellings, for one, as well as his dog’s name or the signed copy of a controversial book. And he also remembers his latent homosexual desires, which never came into fruition.

The story is elegantly told, fast-paced, and includes philosophical reflections at the right moment

The orphan tells his story as if he was sitting next to you at the bar. He addresses you directly, laconically almost, throwing in a joke here and there, which turns the reader into a kind of accomplice. This style works amazingly well, especially in a short novel like Wolfsjong, which you can easily finish in one sitting one lovely evening. The story is elegantly told, fast-paced, and includes philosophical reflections at the right moment. When the orphan and Oskar find themselves in the woods together admiring a wolf, the latter respectfully states, ‘That little creature lives a beautiful life. He has no purpose.’ Van Vliet is able to carefully dose his information, deviates from the story at the right times, but always swiftly returns to the core of the tale, i.e. the friendship between the orphan and elusive Oskar.

Life is not kind to the young narrator either. His recently deceased father left behind enormous debt, which leads the nineteen-year-old to be hunted down by bailiffs. Despite that burden, he must try and step out of from his father’s shadow and build a life for himself. In fact, that perfectly mirrors Oskar’s life, who, whichever way he tries to justify it, was never spoilt by his procreator either. In this story, we meet more than just one lost prodigal son. This is what makes Wolfsjong a beautiful fable about who we are, and about who we would rather be, the image we like to portray towards others. Especially while hanging at a bar.

However, seeing the friendship was so brief, the orphan is left feeling forever uncertain. Did this friendship mean as much to Oskar as it did to him? Or did he merely convince himself he would be able to mean something to another human being? Years later, those feelings of doubt have become part of him.

Many years after his death, we finally find out Oskar’s secret, when the narrator meets someone at a bar who looks just like Oskar. Young Otto turns out to be very familiar with Oskar’s story – What’s more, he turns out to be part of it. In the end, the orphan finds another person to share a drink with and talk to, with whom he can laugh about love lost and broken dreams. And eventually, things all fall into place for him as well.

Excerpt from ‘Wolfsjong’, as translated by Paul Vincent

pp. 9-10

My father died as he had lived: alone and in silence, while the night nurse was looking the other way. I was sleeping at home that night. During the funeral it rained. Everyone was in black, no one cried and the vicar read out a leaden Bible text over sin.

In the days after father’s death, his nieces and nephews unfolded a camp bed in the attic and occupied it in turn, convinced that I derived comfort from their company and involvement with the choice of casket, flowers and music. Once father was finally in the ground they did an about-face and left for a distant home. I hoped never to see them again.

In the days after the funeral I did not want to see or speak to anyone. The curtains were closed, I did not open the door to anyone and I tore the plug of the telephone out of the wall. When my father was alive hardly anyone rang. In those days vendors still came to the door and my father had no friends. After his death suddenly half the village was on the line. They thought it was so awful that I no longer had a father, but they were certain he was in heaven and I could always turn to them for help. A lie, of course. There are simply times when you can’t turn to anyone, not even your nearest and dearest. On weekdays between three and four in the morning, for instance.

I sought comfort in imagination, a very good distraction from anything at all. The morning after the funeral I got a pile of books from the library. I forget what exactly. In my teens I most liked reading about ancient civilisations: powdered dowagers, servants in livery, family fortunes; British aristocrats with stand-up collars, the points folded over, in a landscaped garden; commercial travellers in snow-white linen, strolling among the tame elephants in British India. Tales that I did not read for their story, drama or plot, but for the forms, the table manners, the materials, the flowers, the dinner service, the newspaper headlines, the evaporated period aroma. I had grown up in a cramped terrace house where we ate Dutch stew and very exceptionally macaroni, without napkins and always with our elbows on the table.

The stories that moved me and still do, were about brotherhood. Naughty boys in the harbour, card-playing sailors in white shirts, soldiers dying in each other’s arms, you know. I was (and am) an only child and I had often prayed for an older brother. And friends, real friends, I never had in my youth, although I went round the whole time with Werner the neighbours’ son. Werner and I liked wandering around building sites as soon as the builders had gone home. We had to check out of the corner of one eye that we did not tread on an upright rusty nail, and out of the other that a shovel did not slide off a wobbly length of scaffolding. Once, in a corner house still under construction – we must have been about six – I had to shit, and emptied my bowels squatting above the crawl space. Werner had gone to look for toilet paper and had come back with glass wool, with which he rubbed my arse clean but also full of glass fibre. It was already dark when we got back to the street, where the local policeman stood waiting for us. My mother and Werner’s were in our house, pale as ghosts. I squealed like a sucking pig, crazy with itching, and was bleeding from all the scratching. The village doctor had come to make my bottom better. From that afternoon on I was no longer allowed to play with Werner. ‘A boy like that just brings trouble,’ father had said.

Werner was now studying in town, wore his hair long and ignored when we passed each other in front of his parental home.

Kevin van Vliet, Wolfsjong, Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2019, 96 pp.