From Harlotry To Sex Work: How The Low Countries Deal With Prostitution

In the history of paid sex in the Low Countries, tolerance alternates with repression. Today, prostitution has been legalised in the Netherlands and decriminalised in Belgium, but the normalisation of ‘sex for money’ is far from a reality.

Where there is commercial activity, there is also commercial sex. With the flourishing of cities in the Southern and Northern Netherlands, a sex industry avant la lettre developed since the late Middle Ages. Local and “foreign” craftsmen, traders, seafarers, soldiers, artists, students and diplomats could indulge in brothels, stews (bathhouses), taverns, inns and “playhouses” that offered a wide range of entertainment, depending on the budget. Religious and secular authorities did not condone “fornication”, but treated prostitution as a necessary evil that needed to be regulated, or at least tolerated, to prevent worse from happening.

Between the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, tolerance alternated with repression in port cities such as Amsterdam, Antwerp and Bruges, trade centres such as Ghent, Leiden and Leuven and bastions of power such as Brussels and The Hague.

Napoleon Bonaparte brought about a significant change. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, he introduced a modern regulatory system to prevent the spread of venereal diseases. A detailed control system was intended to protect the entire population against unregulated prostitution.

After Napoleon’s final fall in 1815, many European countries held on to that system to keep the so-called oldest profession in the world in check. But not all European rulers were convinced. While Antwerp, Brussels and Paris were keen on regulation, the British and the Dutch much less so. They paid particular attention to the garrison towns and colonial areas. London, for example, never implemented the system. Amsterdam did, but in a very different way than with the rules and regulations that characterised Belgian cities.

Historical photo of two sex workers

Historical photo of two sex workers© FelixArchief

Belgium had a reputation for being a “hyper-regulated” country. In theory, Belgian regulation was not only supposed to prevent diseases but also offer some degree of protection to registered prostitutes. In practice, the system exercised strict control over women who sold sex. Not only were they obligated to register, but they were also subjected to painful and humiliating medical examinations, made to work at maisons closes (state-controlled legal brothels) and had to stay away from churches and schools.

The Amsterdam authorities and the population in general were not keen on this harsh approach. Not because they already considered prostitution as a form of work, but because they acknowledged the inefficiency of the system. The idea that prostitution was the symbol of patriarchy also took shape and contributed to international criticism of the regulatory system.

Abolitionism and prohibitionism

Starting in the second half of the nineteenth century, criticism became increasingly stronger. The British abolitionist movement, which sought to end the regulation of prostitution, spread rapidly. Abolitionism means that prostitution itself is not prohibited, but rather its organisation. In other words, the sale of sexual services is not an offence. Advertising, running a brothel or helping with the bookkeeping are.

The abolitionists had strong arguments: the regulatory system was not only inefficient and immoral, it was criminal. Venereal diseases would continue to spread as long as immorality prevailed and men followed their sexual urges unrestrained. Abolitionists also argued that regulated brothels led to ‘white slavery’ The double standards that characterised the regulation, coupled with the fear of human trafficking, made the system untenable.

The abolitionist movement achieved one of its first successes in Amsterdam, introducing a brothel ban in 1897. A national Dutch abolitionist policy was introduced in 1911. Belgium, on the other hand, waited until 1948 to abolish its regulatory system. Both countries chose abolitionism because they did not agree with the outright ban or prohibitionism that existed in the United States and the Soviet Union.

But contrary to what the abolitionist movement had hoped, the introduction of the new legislation did not lead to the end of commercial sex. Prostitution henceforth became a clandestine activity which was certainly not unknown to local authorities. The sexual revolution of the 1960s contributed to the laissez-faire policy or “unregulated tolerance” that prevailed in post-war Belgium and the Netherlands.

The struggle of sex workers

The last decades of the twentieth century brought change again. The growth of the prostitution scene, increasing migration and concerns about the AIDS epidemic and crime led to a revision of the policy. Drug trafficking and human smuggling were (once again) linked to commercial sex, meaning that there was no longer such a thing as happy hookers, but rather “sex slaves”.

A new player also made its appearance: the sex workers’ movement. This led to a new discourse around prostitution. Women in prostitution had already made themselves heard in previous decades, but it was not until the 1970s that there was an organised battle. Prostitution was defined as work for the first time, and the term “sex worker” became more common.

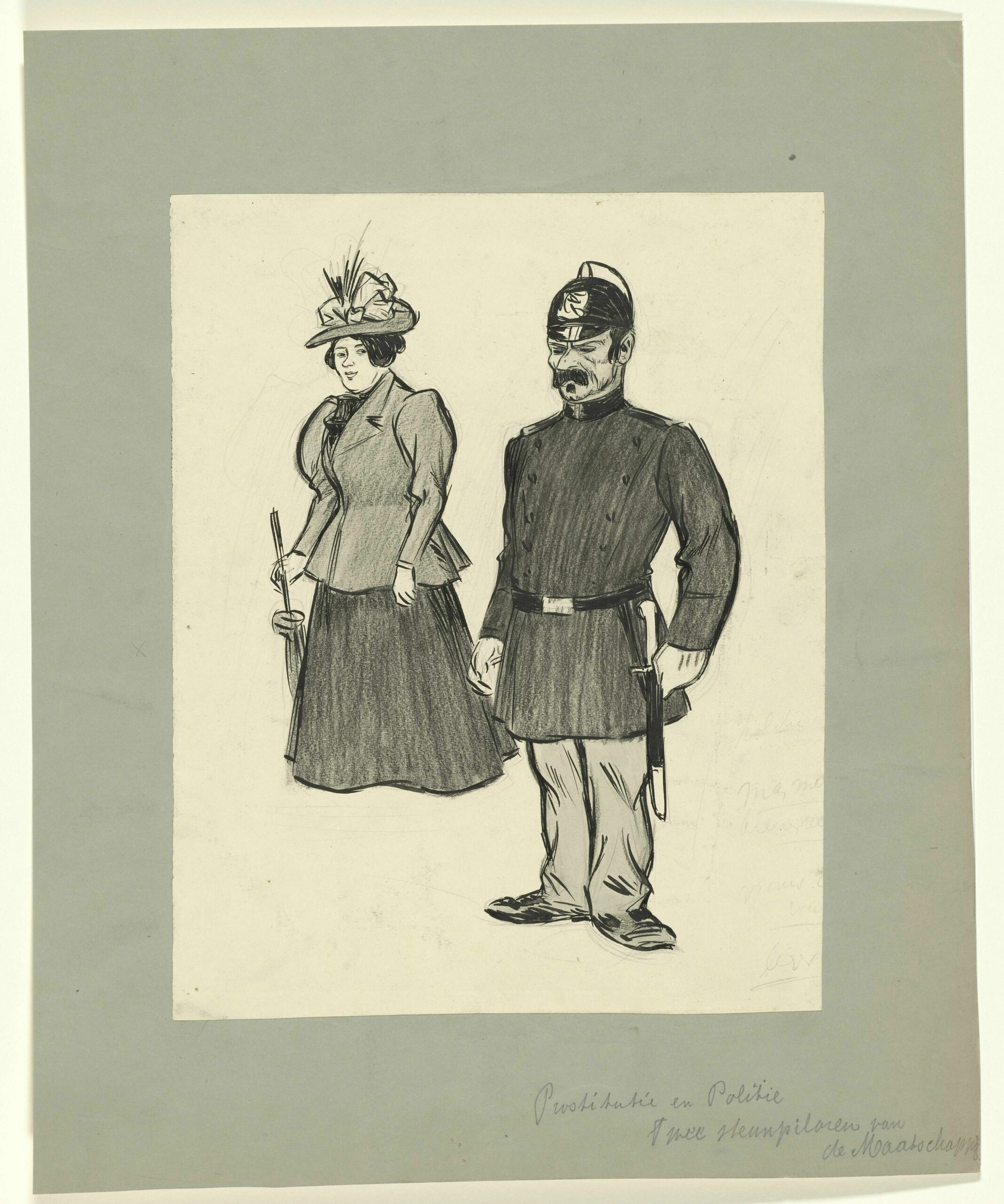

Prostitution and Police: Two Pillars of Society, drawing by Jan de Waardt, 1885-1909

Prostitution and Police: Two Pillars of Society, drawing by Jan de Waardt, 1885-1909© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The pioneers of the sex workers’ movement came from the United States and France, but Dutch and Belgian sex workers and supporters from the health sector also quickly took to the barricades. They fought for more rights and government protection.

Around the turn of the century, this activism led to the legalisation of prostitution in the Netherlands, while Belgium continued to fluctuate between de facto regulation, tolerance and repression. Yet both countries had the same goals in mind: the limitation of commercial sex to well-defined zones and the fight against human trafficking.

The well-being of sex workers came only in second place. Thus, local and international activists worked closely with aid organisations and academics to challenge the increasingly strict nature of legislation in the Netherlands and the legal uncertainty that sex workers faced in Belgium.

It was and still is a difficult battle. After all, defenders of prostitution as a form of work are up against a strong “neo-abolitionist” camp that makes no distinction between voluntary and forced commercial sex. This view is central to the so-called Swedish model, which criminalises clients of prostitution.

The European Union was inspired by that model and launched a non-binding resolution in 2014 advising member states to adjust their prostitution policies so that “the sexual slavery of women” would be eradicated. France followed the advice and criminalised the customer; Belgium did the opposite.

The COVID-19 pandemic motivated the Belgian government to approve the decriminalisation of prostitution

The COVID-19 pandemic led to human dramas and motivated the Belgian government to approve the decriminalisation of prostitution. The hope is that decriminalisation will create a system that is more flexible than Dutch legalisation, in which the protection of sex workers is balanced with the fight against rogue individuals. The question remains to what extent the implementation of the new law will provide a better understanding of the entire sector and its destigmatisation.

Other roles

Regardless of policy differences, Belgian and Dutch authorities consistently focused on female prostitution. Male intermediaries and customers only received attention if they caused problems or went to the police with complaints about sex workers. Brothel madams occasionally appear in historical sources, but the elites were particularly obsessed with “fallen women”. That “normal” women would consciously choose commercial sex over poorly paid but “respectable” jobs was considered impossible.

The Netherlands adhered to this logic until the end of the twentieth century. Until that period, foreign sex workers were not given a work permit because they were supposedly “not mentally mature enough” to assess the consequences of prostitution. This way, sex workers from outside the European Union ended up in the Dutch illegal circuit, or they benefited from the tolerance policy of Belgian cities such as Antwerp or Ghent and the absence of any policy in Brussels municipalities such as Saint-Joost-ten-Noode.

Regardless of policy differences, Belgian and Dutch authorities consistently focused on female prostitution

There is also a striking development when it comes to the places where paid sex takes place. Since the turn of the century, local authorities in Belgium and the Netherlands have tried to restrict prostitution to tolerated or legal workplaces, but new technology has led to more mobility and self-employment. Just as more public transport, telephones and cars made access to prostitution easier in the twentieth century, the internet and smartphones now provide greater information flow and more independence for sex workers.

The famous De Wallen in Amsterdam, the Schipperskwartier in Antwerp, the Glazen Straatje in Ghent or the plethora of Chaussées d’Amour in Flanders still appeal to the imagination, but such red-light districts still represent only a small segment of the sex industry. The majority of paid sex escapes the public eye.

De Wallen in Amsterdam still appeals to the imagination, but such red-light districts still represent only a small segment of the sex industry.

De Wallen in Amsterdam still appeals to the imagination, but such red-light districts still represent only a small segment of the sex industry.© Wikimedia Commons

This holds even more true for male and trans sex workers who have long been simply ignored. This only changed in the 1980s and 90s when the AIDS crisis struck, and many young men and trans women from Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Latin America came to the Low Countries. Before that, men, transvestites and transgender people were already present in places that female sex workers also frequented. And their customers weren’t just men. For example, La Pergola in Brussels mainly attracted a female clientele. But, as Brussels lesbian activist Suzan Daniel pointed out, men alone or older hetero couples “looking for someone to fool around with” were also welcome. Places like La Pergola were not brothels but nightlife venues where both paid and unpaid sex took place.

Het Glazen Straatje: this nineteenth-century shopping arcade is the heart of Ghent’s prostitution area.

Het Glazen Straatje: this nineteenth-century shopping arcade is the heart of Ghent’s prostitution area.© Wikimedia Commons

Female clients of gigolos or lesbian sex workers were (and still are) usually more discreet than men involved in commercial sex. Moreover, the purchase and sale of sex remains taboo in 2023, regardless of the gender of those involved. This makes scientific research more difficult, but sexual emancipation and higher participation of women in well-paid jobs have certainly increased the demand for “male companions”. Unlike in previous decades, women don’t have to go to the opposite side of the world to find sanky-panties.

Just like legalisation in the Netherlands, the decriminalisation of prostitution in Belgium will not automatically lead to its normalisation. Only the main actors in the sex industry – sex workers and clients who openly talk about their motives and experiences – can make this possible. This openness would also help to detect human trafficking and other wrongdoings related to the sector on time.

Sources

- Elwin Hofman, Magaly Rodríguez Garcia and Pieter Vanhees (eds.), Seks voor geld. Een geschiedenis van prostitutie in België, Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2022

- Synnøve Økland Jahnsen & Hendrik Wagenaar, (eds.), Assessing Prostitution Policies in Europe, Routledge, London/New York, 2018