Publishing in 2024: Scatter Gun or Targeted Shot?

Big publishers of literature are suffering hard times, while smaller niche players appear to be doing pretty well. So which direction should publishing take? A publishing director, a publisher-bookseller, a freelance journalist and an author exchange thoughts on the future of the book. ‘Readers have limited time. As a publisher, you have to bear that in mind.’

Over the last few months, Bart Van Loo sold another 12,000 books. A new edition of his book Napoleon from 2014, with a new foreword, easily found its way to readers. The impetus for the republication was Ridley Scott’s film, an epic with inevitable inaccuracies. Publisher De Bezige Bij was able to counterbalance that with Francophile Van Loo’s excellent reputation and historical knowledge. A robust promotional campaign did the rest.

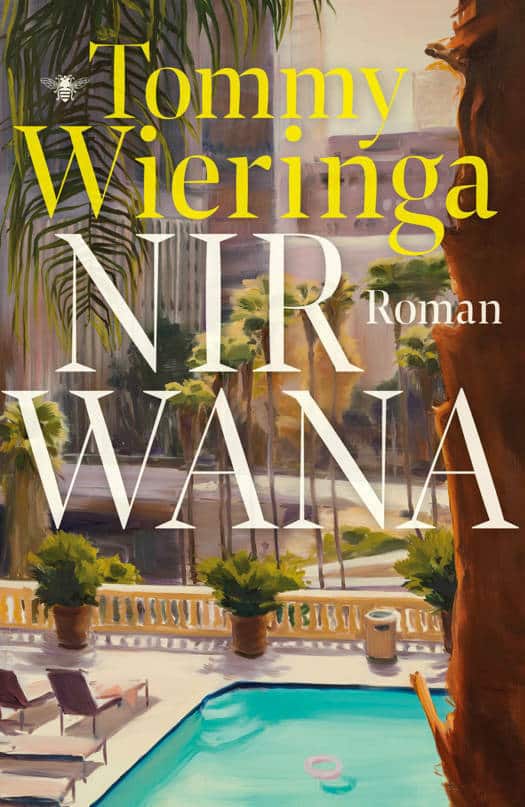

Twelve thousand books: many authors would give their right arm for such sales figures, while Van Loo achieves this with a reissue. “He’s an unprecedented talent, after all, a born storyteller who easily brings his books to a broad readership,” says Van den Nieuwenhof. It immediately illustrates one of the difficulties of her profession: writers also have to lead the promotion of their books themselves, and not everyone is as skilled at that as Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer or Tommy Wieringa, who attracted people en masse to book shops and theatres in 2023 for the presentation of their new titles. “If you have a somewhat shy debutant, it’s more difficult by definition. In the past, a positive review could sometimes make the difference, but we see that happen far less these days.”

Moreover, competition for the Dutch-language book is very stiff. Streaming services such as Netflix, as well as podcasts, lure readers away from books, and those who still read increasingly do so in English, particularly young people. There you have it: the big challenges for those selling literature, poetry and literary non-fiction in Dutch.

Focus on books

Van den Nieuwenhof has been publishing director at De Bezige Bij since November last year, having previously been head of sales and marketing for the same publisher, and having worked before that in an equivalent role for Prometheus. Her latest appointment was the result of two rounds of redundancies within a few months at De Bezige Bij, the first of which saw publisher Francien Schuursma leave, followed by director Mark Beumer and nine other employees.

Romy van den Nieuwenhof (De Bezige Bij): 'In the past, a positive review could sometimes make the difference, but we see that happen far less these days.'

Romy van den Nieuwenhof (De Bezige Bij): 'In the past, a positive review could sometimes make the difference, but we see that happen far less these days.'© Keke Keukelaar

Did Van den Nieuwenhof feel good about taking the helm in such circumstances? “The reason I said yes is that I have a strong opinion on which direction to take. So I felt that I had to demonstrate that. The reorganisation at De Bezige Bij was financially necessary, but it’s also very much structural. Previously, we had a director who was involved with the financial side and a publisher who worked on content. I had no interest in doing just one of those things because to me they are inextricably linked. That’s why I said yes to this position. I genuinely believe that De Bezige Bij can be a high-quality publisher and at the same time a financially sound business.”

How? According to Van den Nieuwenhof that has to do with a great many business decisions on print runs, stocks, paper prices and the like, but it also has to do with focus. For a while, De Bezige Bij ran its own speakers’ agency, and there was substantial experimentation with podcasts. But to her the focus really belongs to the books, where she also argues for firm decisions and publishing fewer titles.

Fifty books a day

Van den Nieuwenhof touches on a sore point there that has been the topic of squabbling in the publishing world for years: too many books are being published in the Dutch-speaking region, 20,000 per year altogether, more than 50 books a day. Not all of those are literary novels, to be sure, but all those books demand budget, attention, and care, not to mention buyers.

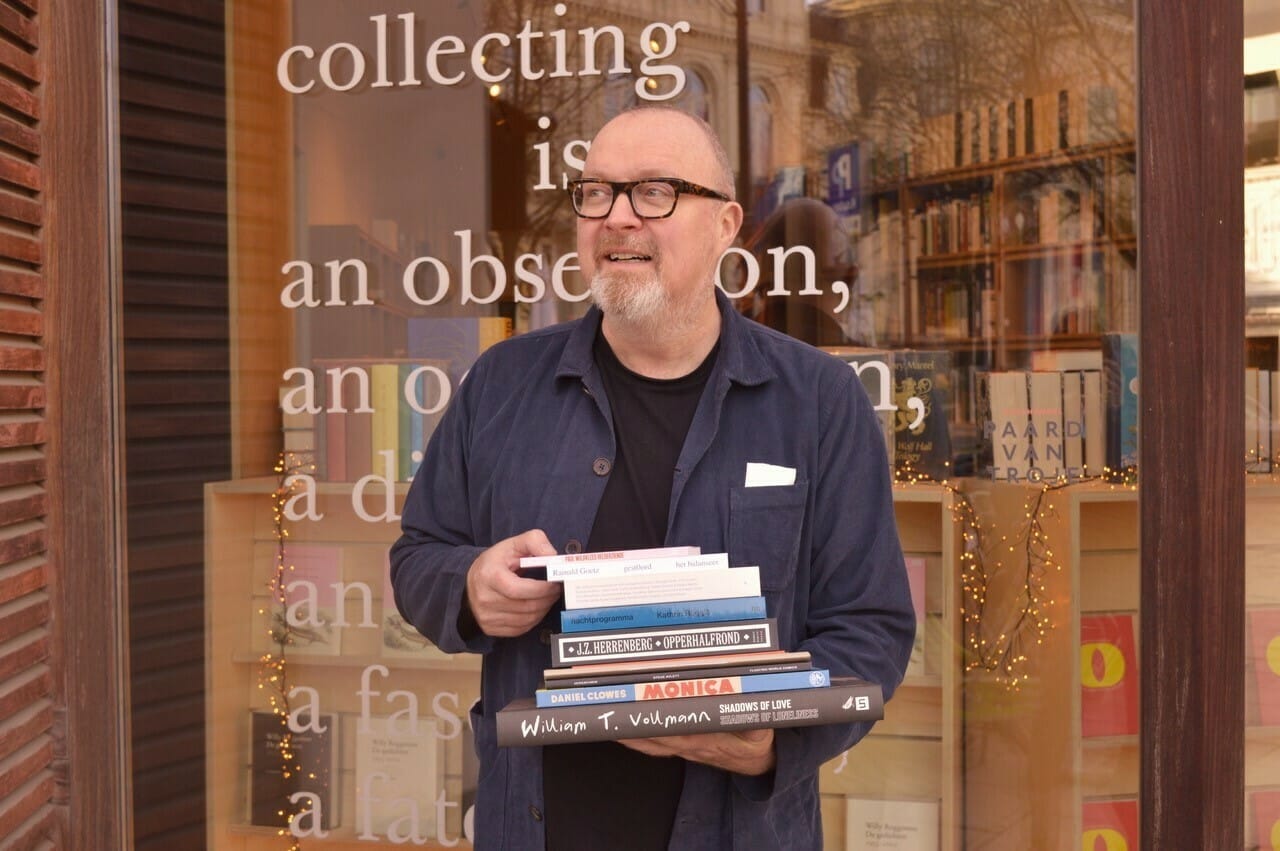

“A great deal is published, and I’ve been hearing for years that the tsunami of books should be stopped, but I don’t see any sign of that happening,” says Kris Latoir. He started the publishing house het balanseer (no caps) in 2007 and has also been the manager of the bookshop Paard van Troje in Ghent for several years. “If we pile up the promotional leaflets from publishers in the shop, we end up with quite a tower. That’s not just a concern for the bookseller, readers have limited reading time too. I think as a publisher you have to take that into account.”

Publisher Kris Latoir: 'We do this out of love for a particular kind of literature that we think receives too little attention from the big publishers.'

Publisher Kris Latoir: 'We do this out of love for a particular kind of literature that we think receives too little attention from the big publishers.'© het balanseer

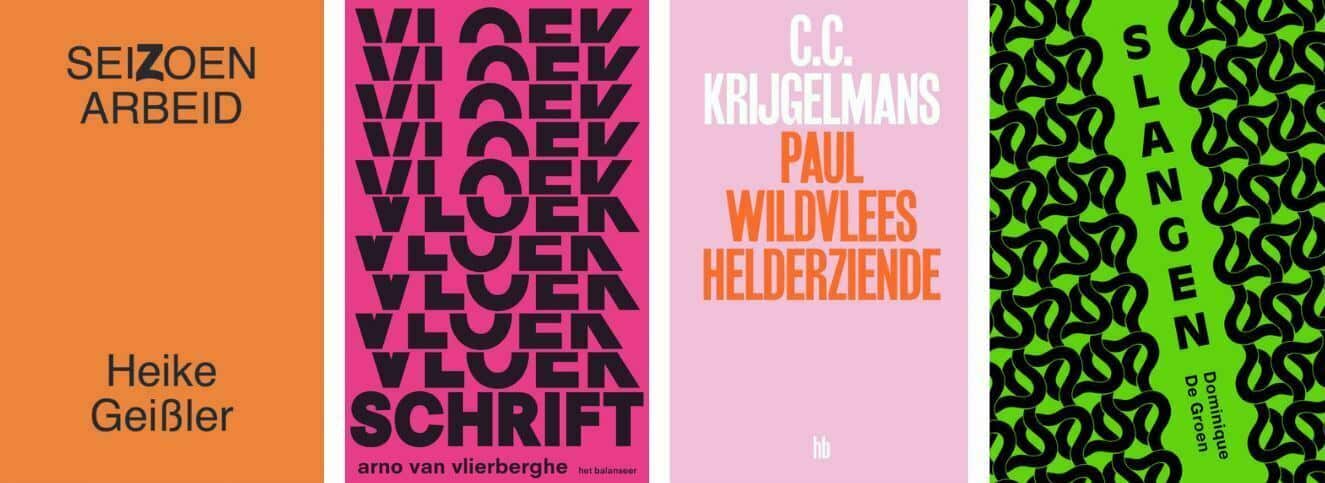

The irony is that Latoir’s publishing company came into being because De Bezige Bij’s old Antwerp branch couldn’t get the green light from the head office to publish the collected work of Claude Krijgelmans (1934-2022). That’s why Latoir and four friends set up het balanseer, named after one of Krijgelmans’ stories. It was intended as a one-off project to honour one of the innovators of Flemish literature, but then people came to them asking to republish other Flemish authors, such as Willy Roggeman and Pol Hoste. In doing so, het balanseer gained a name as a publisher of Flemish “Ander Proza” (experimental prose), the literature of the counterculture after the Second World War. “That small scale and focus is an advantage, defining a clear target group. But the association with Ander Proza was an obstacle to some readers, so you shouldn’t allow yourself to be pigeonholed too easily. Of course, you want to reach as many readers as possible.”

Latoir achieved that by also publishing original work by new names such as Arno Van Vlierberghe and Dominique De Groen, themselves readers of het balanseer books, who therefore had all the necessary affinity with the publisher, and who do not shy away from the limelight. But that does not in any way mean that Latoir has ambitions to become a big publisher. “We once brought out ten books in a year, but that’s already too much for us. We aim for a maximum of six to eight titles. This year there are seven, including Heike Geißler’s new book.” Latoir’s company previously published this German author’s book Seizoenarbeid (‘Seasonal Work’), which, by het balanseer’s standards, was a success. “Our print runs for poetry range between 300 and 700 copies, for the novels we have to have more than 1000. But we’ve never sold more than 3000 copies of a title. We do this out of love for a particular kind of literature that we think receives too little attention from the big publishers. By also paying extra attention to design, we’ve created our own signature.”

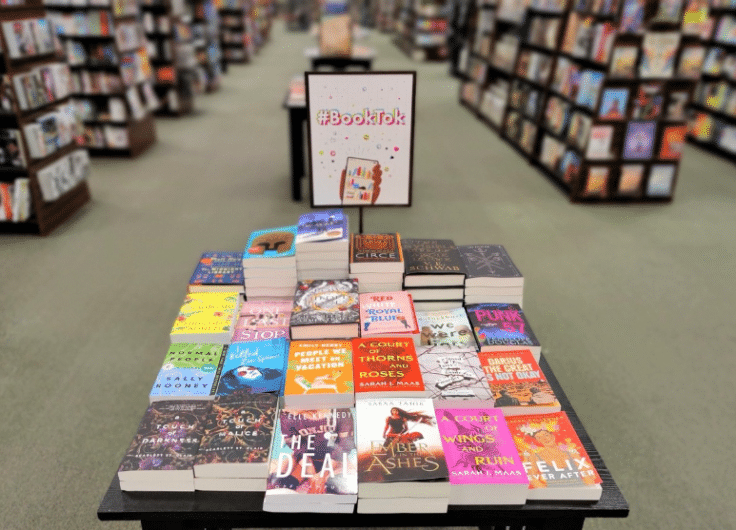

Influencers

For small publishers that focus can work. Literary niche publishers such as Vleugels, Oevers or Koppernik have also expanded to create small but successful portfolios and have a rock-solid reputation. “But it’s really the larger publishers who need diversification,” Maarten Dessing, a literary journalist for Het Boekblad

and the low countries, believes. “The publishers that are having difficulties, such as De Bezige Bij and Atlas Contact, are those who are especially focused on the better book. They can’t cover potential losses with revenues from feel-good literature or cookbooks, for example. I think De Bezige Bij will be doing that more, with Thomas Rap and particularly Cargo, which publishes non-fiction as well as commercial fiction. Last year they had a bestseller with Komt goed. Hoe je ondanks alles tóch leuk moeder kunt zijn (‘It’ll be ok. How to have fun being mum in spite of everything’), a book by Annemarie Geerts, a mother of eight who became famous through her Instagram account @demammavan.”

Romy van den Nieuwenhof acknowledges Geerts’ achievement and the importance of Cargo’s commercial successes for De Bezige Bij. “Komt goed is a book that ties in well with her followers on Instagram, it was a really great success. But not every influencer’s book works equally well. Their target group needs to enjoy reading books. All too often you see books by influencers that are too far removed from their followers. Then it doesn’t work.”

Literary journalist Maarten Dessing: 'I’ll never say that too many books are being published. It’s a question of supply and demand.'

Literary journalist Maarten Dessing: 'I’ll never say that too many books are being published. It’s a question of supply and demand.'© Gerard Stolk / Flickr

In Dessing’s view, the triumph of an influencer book like Komt goed illustrates the fact that publishers continue to bring books to the market on a grand scale. “I’ll never say that too many books are being published. It’s a question of supply and demand. People read, and as long as they do, there will be businesses attempting to reach readers. And as long as they sell enough in the end, they’ll continue, although I’m gradually seeing a trend for publishing less, also because in certain genres, including the literary novel, things simply aren’t going so well. In the past, you could easily publish more than ten novels knowing that you could sell 2000-3000 of each. As long as you keep your costs down, that would make you some money. At the same time, I see that certain publishers, such as Prometheus, still tend to market as many books as they can, hoping that there will be a bestseller somewhere among them.”

Targeted bullets

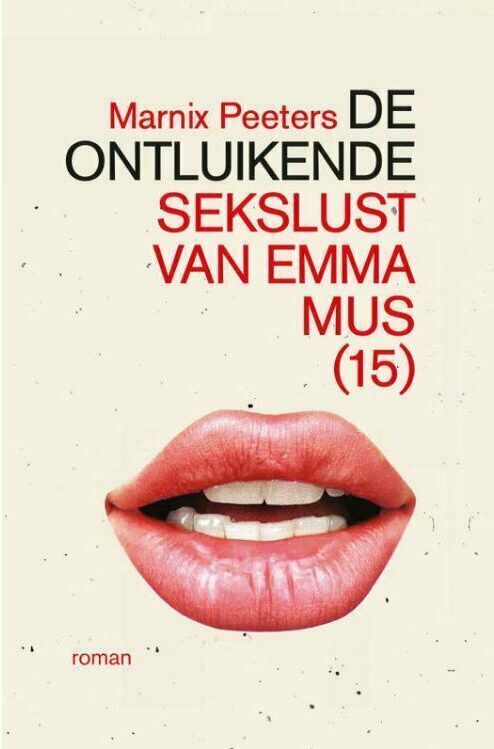

Someone who detests the so-called scattergun approach and would prefer to see publishers opt for a few targeted bullets is author Marnix Peeters. The former journalist debuted in 2012 with De dag dat we Andy zijn arm afzaagden (‘The day we sawed Andy’s arm off’) with De Bezige Bij, where Robbert Ammerlaan was director at the time. “We succeeded in publishing a sneak preview in the newspaper De Morgen. It was a massive success, and that’s how I was launched as a writer.”

Peeters then published through Prometheus, Hollands Diep, De Arbeiderspers and several other publishers, but didn’t find his groove anywhere. “Publishers expect writers to do their own promotion, but many writers simply aren’t familiar with that world, so they just float around a bit. Fortunately, I did know that world and had enough doors to knock on. But I became increasingly irritated by the scant remuneration I received for a novel. That’s why, along with my wife (journalist and social media expert Jana Wuyts, DV), I started thinking about how to approach it differently. That gave rise to the idea for Pottwal Publishers.”

Writer Marnix Peeters self-publishes his books: 'I think I earn over a third more from a book'

Writer Marnix Peeters self-publishes his books: 'I think I earn over a third more from a book'© Koen Broos

The idea can be briefly summarised as follows: Peeters provides a traditional publisher with a finished manuscript, including design; the publisher prints the book and arranges distribution; Peeters does the promotion. It worked, but Peeters continued to be frustrated by the publishers’ distribution system. “Every publisher has a deal with the Centraal Boekhuis, which can deliver very quickly to booksellers, but that also costs a great deal of money. Why doesn’t the book world adopt the just-in-time model used in other industries? As if readers can’t wait three days for a book.” Peeters acknowledges that the Centraal Boekhuis works efficiently, but is frustrated by the fact that this rapid distribution makes up 10-15 percent of the book price. Add to that 35-45 percent for the bookshop and 20-35 percent for the publisher (for printing, design, editing, and promotion) and that leaves 10-15 percent for the writers themselves.

“In the entire chain, the margins are quite wide, but that doesn’t make it through to the author, who should really be rewarded for their work. It’s unsustainable,” Peeters feels. So he and Wuyts decided to take matters entirely into their own hands. For Boef, Jana Wuyts’ first book, they negotiated a distribution deal with the Flemish chain Standaard Boekhandel. For their subsequent books they did everything themselves, turning their living room into a distribution house. “I really don’t think a writer loses much creativity by spending a couple of days filling boxes,” Peeters laughs. The lion’s share of independent booksellers agreed to his proposal to buy directly from him. They order in sets of five and waive the right to send back unsold copies for a refund, as is normally the case with publishers. “Decent booksellers can estimate whether they’ll sell five or 35 copies of my work. Well, 98 percent of the bookshops went along with it without complaint.”

For his latest book De ontluikende sekslust van Emma Mus (15) (‘The Budding Sexual Desire of Emma Mus (15)’), Peeters again went to work in this way. “I think I earn over a third more from a book this way. That comes closer to fair compensation, compared with the handouts from your average publisher. The only disadvantage is that I can’t order reprints, as that would eat away too much of the initial profit. So I have to carefully estimate how many books to have printed.”

Do they actually want to sell?

Peeters realises that for a debut author with little knowledge of the world of literature and journalism, it may be rather more difficult to work the way he does. Nevertheless, he wonders why more writers don’t try to publish under their own steam. He enjoyed shaking the world up a little. “But even if as a writer you opt to work with a traditional publisher, I think both publishers and writers need to be more business-minded. With some authors, I wonder whether they actually want to sell books at all.”

The idea that things could be more business-like or commercial has pretty much everyone’s agreement. “Books won’t sell themselves. These days you need a sophisticated social media strategy to reach readers. A lot of resources go into that too, but that’s almost unavoidable,” Dessing believes. “I want to combat the idea that publishers are hugely conservative and resistant to evolving. They do evolve, but it’s not easy to compete with a company like Amazon, that can afford to sell books at a loss. I see plenty of publishers trying new things. Lannoo, for instance, has three people working full time on the technological aspects of new concepts for publishing or distributing books, using sites like My Talent Builder.” That’s an online talent platform which complements a series of management books.

Building up a readership

Dessing, Latoir and Van den Nieuwenhof are wary of saying that it’s all doom and gloom in the world of literature. Bestsellers are still published, even if Van den Nieuwenhof acknowledges that a bestseller of 150,000 copies is an enormous exception. The ceiling is now closer to 100,000, as De Bezige Bij experienced with Tommy Wieringa’s Nirwana.

Van den Nieuwenhof believes that publishers should be aware of the many ways in which the public engages with stories. “It’s not just Netflix, you also have podcasts, e-books, audiobooks. You can’t ignore that. But it might be better to ensure you have a good partner there, rather than trying to do everything yourself. The earning model for media such as audio is simply much more difficult than for physical books and e-books, you have to take that into account.”

Is it a matter of going back to basics for De Bezige Bij then, focusing on classic publishing? “In the last few months, I’ve often been asked what I would do radically differently. The question is really whether that’s necessary,” says Van den Nieuwenhof. “I don’t think we were on the wrong track when it came to our publishing policy. In some periods you’re building a new fund or new authors. You have to give those new authors a chance to grow, to build up an audience. Perhaps we were just a bit unlucky to have had a lot of those kinds of titles in the last few years. And then you do have to hope that one achieves prominence over the others. Take Lisa Weeda’s Aleksandra, for instance: she worked on that for years with her editor. Just after that book emerged, the conflict in Ukraine began, which brought a boost in sales. I found it hopeful to see that people reached for literary fiction to help them interpret a war like that, that they looked for the empathic side of literature. You saw the same thing during the coronavirus pandemic when Albert Camus’s The Plague suddenly became a big selling success. That does leave me hopeful for the future of the literary novel.”