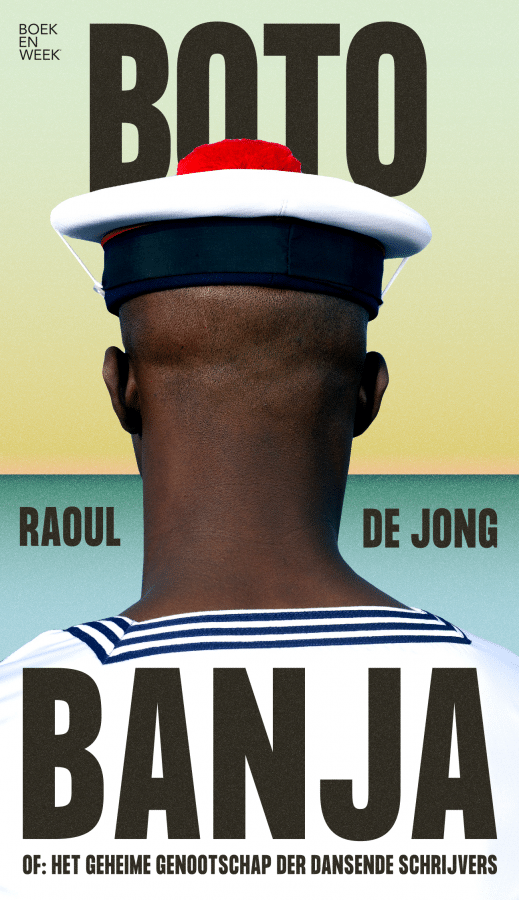

Students Translate Raoul de Jong’s Essay ‘Boto Banja’

Students of Dutch at the University of Sheffield and University College London translated an excerpt from Boto Banja. Of: Het geheime genootschap der dansende schrijvers (Boto Banja. Or: The Secret Society of Dancing Writers) by Dutch-Surinamese author Raoul de Jong. Boto Banja was De Jong’s high-profile CPNB Book Week Essay 2023, a response to the theme Ik ben alles (I am everything), a celebration of the multifacetedness of our identities. ‘Translation is so much more than words on a page’.

In Boto Banja De Jong uncovers a worldwide web of dancing authors who all tell the same story: “A magical, epic, true story that is much bigger than only the Netherlands and Suriname”. It is the story of Anton de Kom and Theo Comvalius but also of the authors of the Harlem Renaissance, in particular Langston Hughes and Nora Zeale Hurston. What they share, according to De Jong, is that they all ‘took to sea’. De Jong decides to follow suit in their honour.

Raoul de Jong wrote a universal story of hope for all humanity

Raoul de Jong wrote a universal story of hope for all humanityDe Jong weaves the tales of the sailing and dancing authors through an account of his own ill-fated voyage from the Dominican Republic to Curaçao. His spiritual journey ends in disaster when the yacht is hit by a hurricane and the crew needs to be rescued by local fishermen. The contrast between the vulnerability of the hopelessly luxurious catamaran (with four private bathrooms) and the effectiveness of the wooden fishing boat (homemade) sets the tone: Boto Banja celebrates the do-ers, the survivors, the believers.

There is something both personal and universal at stake in De Jong’s mission to sail to Curaçao. Yes, he wants to join the Secret Society of dancing authors and yes, he wants to shift the focus of the history of Suriname and his ancestors from suffering and subjugation to strength and survival. But De Jong adds an important extra movement: the story of how the enslaved and their ancestors survived unmeasurable cruelty cannot be sidelined as ‘Black history’. This is a universal story of hope for all humanity. The works of the dancing writers are our guides because they are “so much more than words on a page”. De Jong invites his readers to recognise them as “magic formulas” that can help us, humans, to become the rounded dancers, the everything we carry in ourselves.

Our project

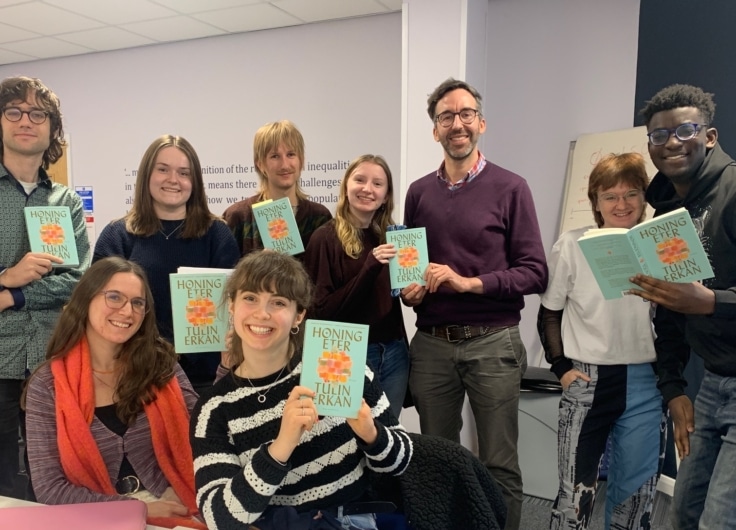

Translating Boto Banja into English seemed daunting at first. How would we, final year students of Dutch at the University of Sheffield and UCL, do justice to such an important and complex text as Raoul de Jong’s Boto Banja? Yet, the challenge was exciting, and we were ready to take it on. Under the guidance of our tutors and the professional translator John Eyck – whose expertise and experience were invaluable when we couldn’t decide on the right words – this project turned out to be something pretty wonderful.

Students of the University of Sheffield and UCL with translator John Eyck and author Raoul de Jong.

Students of the University of Sheffield and UCL with translator John Eyck and author Raoul de Jong.How did we go about it? We all started off by translating an allocated section of the text. Next we got together in small groups and compared our individual translations. It immediately became clear that we all had our own interpretation of and perspective on the text and how specific words and sentences should be translated. Yes, literary translation is so much more than the words on the page! Through discussion and by taking the best bits from each version we produced one group translation to present at our Translation Symposium on 17 December 2024.

In the presence of Raoul de Jong and John Eyck, each group presented their translation and the issues we had encountered: bits we disagreed on, elements we didn’t completely understand, names, places and references that an English reader would perhaps not get.

Being able to ask these questions and having the luxury to work alongside not only a professional translator but also the author of the text was very valuable to us. We learned how a professional would go about textual and cultural friction points, and it was vital to understand how De Jong preferred his work to be interpreted and how we could execute his wishes.

In the final phase of the project an editorial team of students spent a few weeks fine-tuning the translation and making any edits suggested during the symposium to produce a final version everyone was happy with. All this under the guidance of John Eyck. The end product is something we are proud to share, and we feel it reflects the hard work we put into this project.

The Dutch Translation Project has offered us an incredibly valuable insight into the world of literary translation. We became fully aware that you’re not only translating words but also style, culture, and atmosphere. Learning how to keep the flow and tone of the text while also making it accessible to an international audience was a great learning opportunity and one which we will be sure to take into further projects. We all thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to translate such a text as Boto Banja. We hope we have done the original justice.

Libby-Beth Tasker (BA Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Sheffield)

Editors and translators: Elsie Berry, Hannah Bilsby, Isabel Lewis Boyes, Romeo Castillo Pereyra, Tyler Dhoore, Daniel Dimmock, Lukas Durrant, Madog Hendy, Jacob Langford, Esther Moffit, Sophie Moss, Stijn Oosterlinck, Jack Sanders, Ethan Stafford-Cookson, Kyra Sterling-Blake, Libby-Beth Tasker, Klara Van Vlaenderen.

Mentor: John Eyck

Project coordination: Filip De Ceuster (University of Sheffield), Henriette Louwerse (University of Sheffield) and Christine Sas (UCL)

The Translation Project was sponsored by the Embassy of the Kingdom in the Netherlands, London, and the Dutch Foundation for Literature.

Excerpt from ‘Boto Banja. Or: The Secret Society of Dancing Writers’

I had actually wanted to begin this dance in Haiti. On the 1st of July, the day when the Netherlands abolished slavery. Near Cap-Haïtien, atop a mountain named Bonnet à l’Evêque, stands the Citadel Laferrière, a formidable stone fortress. Its first stone was laid in 1805, after thousands of Haitian grandpas, grandmas, fathers, mothers and children had defeated their French oppressors after a fourteen year struggle, founding the world’s first free Black republic. In the 1930s, the fortress was visited by all members of a secret society of dancing writers. Be it in reality, or in their dreams.

I had wanted to climb the Bonnet à l’Evêque just as they had, and there, in the Citadel Laferrière, overlooking the Haitian forests and the Atlantic Ocean, I’d wanted to perform a ritual. But the day before I was due to fly, I got a call from the Dutch poet Maria van Daalen. ‘Don’t do it!’, she said. And when Maria van Daalen says that, dear reader, I take it seriously.

Maria van Daalen is not only a poet, she’s also the only Dutch Vodou priestess to be officially ordained in Haiti. Vodou is the Haitian version of what Americans call ‘Voodoo’, what Surinamese call ‘Winti’ and Brazilians, ‘Candomblé’- one of the new religions that developed as a consequence of slavery. Because of course it’s possible to become a Vodou priestess, even if you were born in Voorburg, in the South Holland province of the Netherlands, and your parents were Protestants and your distant ancestors were shipbuilders from Zeeland, in the south of the country. Once every seven years there is a Vodou conference in Port-au-Prince for which all the priests of the House of Maria must be present. This year it was online, she told me. It was too dangerous in Haiti, even for them.

So the dance begins 120 miles away, on the same island, but across the border, in Haiti’s good little sister nation: the Dominican Republic. The country where Columbus was buried. You know, the ‘explorer of explorers’ or the ‘criminal of criminals’, depending on who you ask. Mere miles from the first European colonised settlement in the ‘New World’ lies a harbour town called Lupéron.

The little town is made up of low wooden and concrete houses painted in pink, blue, white and mint green. From cafés, living rooms and parked cars boom sounds of Bachata, Merengue and other upbeat music that sounds suspiciously like Kawina, a Surinamese music style based on African rhythms that were once used to communicate with supernatural guardian spirits. The people sitting on the verandas of houses and zooming around on scooters look like the people of Paramaribo, the capital of Suriname.

They’re all different shades of brown, wear brightly coloured clothing and smile at me in the same way as the boy behind the counter in the Surinamese sandwich shop in Rotterdam: like I’m their little brother.

As you walk through Lupéron – not too fast, it’s pretty hot – swaying your hips a little to the music, before long you’ll come across a gate. Behind it, the harbour police hang around on a bench in the shade. You’ll say ‘Bon dia’ and dance along a narrow tarmacked road, past tropical plants, until you arrive at a large pool of turquoise water: the harbour.

Bobbing in the water are large, glistening white specks. On these specks live Americans, Europeans and Canadians – other people on the other side of the gate. They have their own parties, their own yoga classes, their own cafes.

Amongst these people, Lupéron is known as a ‘hurricane hole’, a place where they can find shelter with their sailing ships during hurricane season, from late June to the end of November. On top of one of those white specks, I stand, in a sailor suit, at the foot of the stairs to the water. The staircase is covered with gifts that I collected following the advice of Maria van Daalen and the Surinamese-Dutch Winti-priestess Marian Markelo (aka Nana Efua).

These should ensure my safe passage, in the middle of hurricane season, as I sail from here to Curaçao over the coming fortnight. The hurricanes originate in Africa, where they begin as small whirlwinds. Over the ocean they develop into colossal, storms destroying everything in their path. Or not.

“Where shall we start?” asks Dana, the ship’s captain, a blonde Mexican-American woman from Texas.

When I called her back in the Netherlands, she told me the story of a recurring dream she’d had every night from the ages of 10 to 15. She would be sitting in the ruins of a temple when two jaguars would walk past nuzzling up against her and then disappear down some steps. That’s why I chose her- that and the fact her catamaran had four bedrooms, four bathrooms, a living room and a covered deck!

“With Papa Legba,” I say, “he’ll open the gate.”

The night after the zoom call about the Book Week Essay, I’d had a strange dream.

I sat on a sailboat in little sailor suit on the Atlantic Ocean, and I imagined myself to be one of the characters from Banjo, a 1929 novel written by the Jamaican author Claude McKay about a group of Black rascals who washed up as stowaways or sailors in the French port city of Marseille. They spent their days swimming, lounging, singing, dancing and enjoying life without feeling an ounce of shame between them. The rascals came from different countries, different continents, yet there was something they had in common. Something magical, which seems to communicate through colour, dance and music.

When I woke up, I thought of Claude McKay and the secret society of the dancing writers that I had tracked down after the publication of Jaguarman. Anton de Kom and Theo Comvalius were not alone; by the 1930s, writers- descended from the enslaved all over North America, South America, and the Caribbean- boarded ships to tell the world their story. Writers such as Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Aimé Césaire and Claude McKay.

All these writers dressed like kings and queens. In all of their books, I came across words, concepts, myths, legends, gods and expressions that I’d also encountered in the history of Suriname and the books of Theo and Anton. And just like Theo and Anton, all these writers loved to dance.

Theo seemed to allude in his work Iets over het Surinaamsch lied (Concerning the Surinamese Song) that this was not accidental. That there did indeed exist such a thing as a world wide web of dancing writers from all corners of the globe who told the same story at the same time, with just as much flair and panache. A wondrous, epic and true story that was so much bigger than just the Netherlands and Suriname. A story that revolved around oppression and liberation, what lies beyond liberation, and how we, as human beings, can celebrate that. A story that, according to Theo, could have the power to inspire every person on Earth.

“It is therefore wise for us Creoles across America to join hands with our kinsfolk elsewhere […] And when we lie dormant in our graves, our descendants will be summoned to let their voices be heard,” Theo wrote.

Coincidentally, or probably not, I was visited a few days after my Banjo dream by Rachel Gefferie, a Dutch-Surinamese woman who had read my book Jaguarman and sent me a message on Facebook. As it turned out, Rachel was a researcher at the University of Kent, where she studied a magical Afro-Surinamese dance. Just like Claude McKay’s book, the dance got its name from the same traditional African instrument: the Banja. “During the time of slavery, slave owners thought that the Banja was performed for mere entertainment,” Rachel explained. Then, beaming, she added: “But of course they had it all wrong!”

From the moment that the Africans found themselves in slavery, anything that did not match up with the role that the master had invented for them could cost them their lives. That was the role of the ‘slave’ and a slave had to be physically strong yet mentally weak. But that did not mean enslaved people truly were so. It just meant that they had to be twice as clever to survive: they had to learn how to play the ‘slave’ on the outside so that they could remain kings and queens on the inside. Just as Theo wrote in his study on Surinamese music: “One can say more by a shrug of the shoulder, a flutter of the nose or mouth, or with a sound than another could with a hundred words. And yet, one cannot arrest nor persecute him, for he, in actuality, has neither done nor said a thing.”

The Banja was used to relay escape routes and contact supernatural guardians. The dance was so enchanting that slave owners would fall under its hypnotic power, such that the enslaved could then escape without any resistance.

When I asked Rachel if my dream had something to do with the dance she had researched, she cheered “Of course!” She grabbed her copy of Jaguarman and flung it open to the last page, where I had included a dance tutorial for the Banja that I found in one of Theo Comvalius’ books. She continued triumphantly: “The Banja knew many forms, the oldest of which was the Boto Banja- the Banja of the boat- which was performed in many ways, including by men dressed as sailors.”

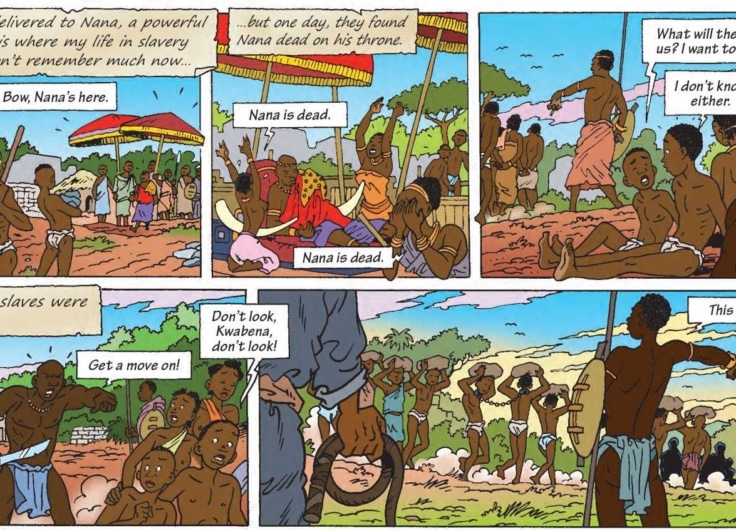

Upon Rachel’s suggestion, I reached out to Nana Efua to get to know more about this boat dance. In the reading nook of her living room in the Hague, surrounded by posters of Black heroes, Egyptian gods, and golden statues of Mama Aisa, the Winti goddess of the Earth, Nana Efua explained to me that enslaved people would tell the story of the passage from Africa through the Boto Banja.

The Boto Banja is still danced, however, according to Nana Efua, never just for the sake of it, only if there is a reason for it. In her explanation it seems the dance serves the same purpose as the family constellation which my aunties and their girlfriends are so fond of: it is danced when there is a problem in the family which goes back many generations. In the case of the Boto Banja it goes back to the first man or woman taken away from Africa on a slave ship.

The whole family takes part in the preparations, which take weeks. A miniature ship is built, food cooked, costumes sewn, rituals carried out and at the end everything comes together in a large event, to which not only all friends and family members are invited, but also ancestors.

The dance begins as the miniature boat is driven in by a group of boys in sailors’ costumes, accompanied by a band. In the ship there are dolls, surrounded by bottles of liquor and flowers, a white doll depicting the slave overseer and Black puppets representing the ancestors who did not swallow their tongues along the way, who did not jump from the ship and who did not die from sorrow. Their living descendants wave the sailors and dolls in with white cloths.

“In reality the boat journey was the beginning of the misery, right?” I asked Nana Efua, to which she mischievously laughed and said: “But you mustn’t forget: we survived it. During the Boto Banja is the beginning of the celebration.”

Later, in Drie Eeuwen Banya (Three centuries of Banya) by the Surinamese poet and anthropologist Trudi Martinus-Guda, I read an explanation of the Boto Banja which seemed to clarify similarities between the stories of the dancing writers: “In that ship they still had their different African gods with them. They arrived in Curaçao, where they were to be taken away from each other. […] One went to Puerto Rico, one to Haïti, one to Suriname, and it was there where we were separated. So the way I see it, whenever we perform such a Banya, we symbolise the power of unity, of reunification. So that you can be filled with this power. And you can be healed.”

The dancing writers were born in different countries, they wrote in different languages. The world called them Surinamese, Jamaicans, Americans and Martinicans, but their ancestors arrived in the ‘New World’ on the same ships. At the slave markets they were torn from each other, as, for example at the one in Curaçao. But the gods who protected them travelled everywhere with them. With the help of these gods they would survive hell on earth and perhaps it was these same gods who let the dancing writers turn back to the sea after the liberation. To tell the remarkable story of their ancestors to the world, whether the world was ready for it or not.

They were thwarted by secret services, laughed at, vilified, and their books were set away on separate shelves. My dream seemed to say that I had to use my crown and my sword to unwrap their gifts and pass them on. This time in a book next to the checkout, a book everyone who made a purchase that week would also receive. By sailing on a ship, just like them, and writing about it. In a sailor’s suit. And if there is anything I’ve learned from the dancing writers, it is that you can take your dreams seriously.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.