Rashif El Kaoui’s ‘De Bastaard’ Translated into English

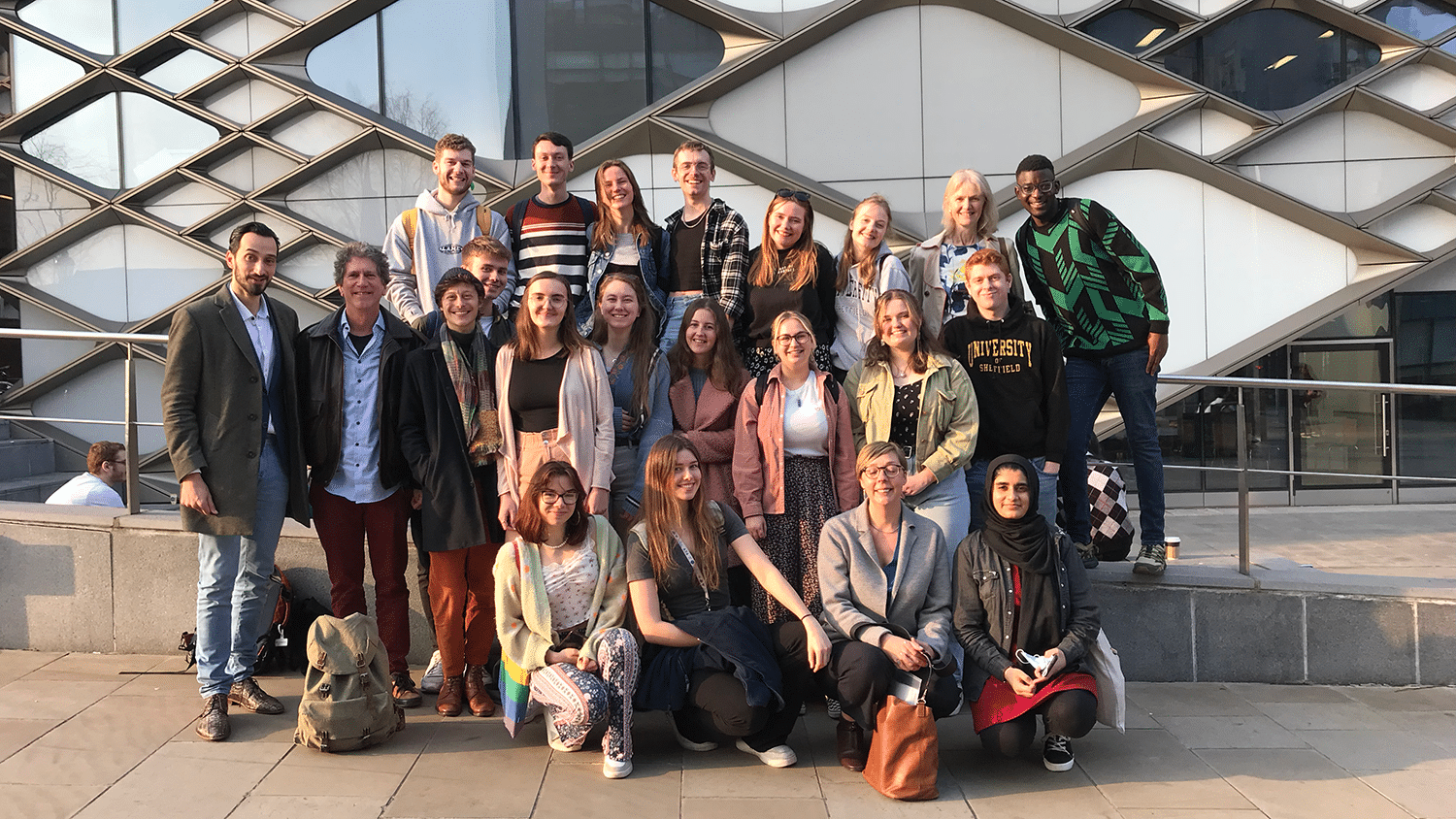

In February and March 2022, students from two British Universities, the University of Sheffield and University College London embarked on a collaborative project to translate an excerpt from De Bastaard (The Bastard), the theatre production by Flemish actor, writer, rapper and podcaster Rashif El Kaoui.

In The Bastard El Kaoui explores his childhood growing up in rural Belgium as the son of a Flemish mother and an absent Moroccan father. He struggles with his dual identity and decides to confront what he has spent all his life brushing under the carpet: he goes in search of his father.

Rashif El Kaoui performing 'The Bastard'

Rashif El Kaoui performing 'The Bastard'© Anna van Kooij

The theatre piece takes the audience on Rashif’s journey into his past, accompanied by his friend and documentary maker, Ahmet Polat, and musician Michelle Samba. El Kaoui travels all the way back to his father’s village deep in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. Although El Kaoui is not afraid to explore this troubled and personal aspect of his life on stage, The Bastard is much more than just a singular story: it is the story of Belgium, of Europe, of the world: “This is the age of the bastard”.

Ahmet Polat, Rashif El Kaoui and Michelle Samba

Ahmet Polat, Rashif El Kaoui and Michelle Samba© Ahmet Polat

Translating works for theatre and performance poses its own challenges. We were acutely aware that the text should not only read well in English, but also work as a performance. Rashif’s specific style of writing and performing was integral to our translation, and we worked on translating his words as well as his voice, his rhythm, his cadence. That ambition, coupled with the many cultural references to both Belgium and Morocco, made this project a very special challenge. We were fortunate to be able to rely on the invaluable guidance and support from literary translator Jonathan Reeder and Rashif El Kaoui himself. Thanks to the support of the Dutch Language Union and Flanders Literature, both were on hand to help us with any questions we had regarding translation issues or cultural queries. Their insights, as well as the help of our professors, meant that we were able to open up El Kaoui’s story for a whole new audience.

John Cairns (University of Sheffield)

Editorial team: Gemma Blacker, John Cairns, June Dawson, Bryony Horsey, Jonathan Reeder

Translators: Hanna Aalen. Gemma Blacker, Jordi Britton, Madelaine Bourn, Connor Bryan, John Cairns, James Cashmore, Lydia Cope, Maddie Cove, Lauren Dalton, June Dawson, Nathanael Fogbel, Tanya Gligorovici, Aiden Gooding, Bryony Horsey, Ana Krech, Barnaby Larter, Karen Lawson, Aza Mohammad, Marta Siwakowska.

Tutors: Filip De Ceuster and Christine Sas

Project Coordinator: Henriette Louwerse

A short video report of the project.

Excerpt from 'The Bastard' by Rashif El Kaoui

I am a bastard, a half-blood, a mongrel. Often a passe-par-tout, more often a passe-par-rien. My X chromosome comes from the gritty Flanders clay, my Y chromosome from the shifting Atlas sands. I shouldn’t exist. I’m problematic. I’m a reminder of a past best forgotten.

I am a bastard. I have a disconnected perspective, because I am always connected. I used to be banned. A baby to throw out with the bathwater.

I don’t take sides because I was born in the space in between. The space in between the extremes. The space where hate takes shape, love burns bright and the axis shifts.

I am a bastard. I don’t take sides because I’m a sodium-potassium pump. I permit porosity. Permeability of the cell wall. I keep sodium and potassium in balance.

I am a bastard. I have to conform to perception. How I am seen is my reality. My reality differs from day to day. Blend in or bugger off. I choose to blend in. I’m diplomatic. Choosing a side is always losing a side of yourself. That’s why I’m a hypocrite, because I won’t nail my colour to the mast.

I am a bastard. Behind my shield I shelter the bastards of the Rhineland, the comfort women of Japan and the lascars in the holds of the East India Company. Joining my ranks are the sons and daughters of Genghis Khan, Hannibal of Carthage and Beethoven, with his Moorish mum. I rally every sambo, mestizo, mulatto, muwallad, beurette, rebeu and half-caste under my banner.

I don’t take sides because I was born in the space in between. The space in between the extremes. The space where hate takes shape, love burns bright and the axis shifts.

I am a bastard, a half-blood, a hybrid. I’m just a “half”. I’m “watered down”. I’m forgiven for much and blamed for more. I’m always apologising. Because I’ll never quite get it anyway. I mostly hold my tongue, because my words carry weight.

I am a bastard. I’ll keep saying it until it stops stinging. I want to bear the name with pride, not shame. I want to wear it as a badge of honour. A blemish on the face for those obsessed with purity. I am Janus with two faces. One focused on the past, the other on the future. I am the god of beginnings and endings, transitions and doorways. No priest keeps my candle burning.

I am a bastard.

(…)

This is a photo of my father when he had just arrived in Belgium.

Sometimes I get so tired of talking about him .

My father was more present in his absence than when he was actually there. Like a kind of cut-out silhouette that reappears in every photo. The shape of something that should have been there; that was once there, but isn’t anymore. Like a stone tossed into a lake, with only the ripples left on the surface. But the stone itself has long disappeared from sight. Sunk to the bottom.

(…)

Ahmed El Kaoui was born in Tingliane, Morocco, a village in the Atlas mountains.

Ahmed El Kaoui had 4 brothers, one died young from a scorpion sting.

Ahmed El Kaoui had 2 sisters.

Ahmed El Kaoui arrived in Belgium at about 8 years old.

Ahmed El Kaoui’s birthday was the 1st December but that wasn’t his date of birth. All Moroccans arriving in December had their birthdays on the 1st.

Shortly after arriving, Ahmed El Kaoui drank a whole bottle of vinegar, thinking it was one of those Western soft drinks.

Ahmed El Kaoui’s father worked in the mines.

Ahmed El Kaoui had to go to a school for miners’ children, where he got good grades. But that didn’t matter. Because boys at that school had to follow in their fathers’ footsteps, good grades or not.

Ahmed El Kaoui had asthma, which forced him to stop working in the mines after a few months.

Ahmed El Kaoui worked in the mines long enough to learn how to drink like a miner.

Ahmed El Kaoui would hop from one relationship to another.

Ahmed El Kaoui wanted people to call him Amadee. This sounded more Belgian.

Ahmed El Kaoui met Christine Adriaens at the Blues Festival in Peer.

On the 11th July 1988, his son was born.

After about a year, Ahmed El Kaoui became a weekend dad, of sorts.

When his son was 11, he told Ahmed El Kaoui that it would be better if he stopped coming round, even at the weekend.

Ahmed El Kaoui fitted windows and doors.

Ahmed El Kaoui had a drinking problem.

I’m tired of talking about Ahmed El Kaoui, but I have to. I feel guilty that this is another performance about a problematic father figure. The director who travelled with me to my father’s homeland, is also called Ahmet. I’m well aware of the irony.

When I asked director Ahmet why we are so obsessed with our absent fathers but not our present mothers, he said:

M: Because they didn’t leave us with any unanswered questions.

M: Why are you on this journey, Rashif?

Because everyone thinks it’s the right thing to do. To go in search of my “roots”. I’ve never been to Morocco before because my father didn’t want me and my mother to go. When he went, he went with his drinking buddy/homeboy, Peter. So, all I remember of Morocco from my childhood are a few pictures: of sand and goats and Peter.

Going in search of your roots, isn’t that what people do when they’re trapped?

M: What’s trapping you, Rashif?

I’m trapped by the gaze of the world around me. I’m trapped by the perception of others. I no longer know whether my inferiority complex is a product of nature or nurture. I can’t light a revolution when others snuff out my flame. Too brown to be Belgian, too white to be Moroccan. Munafiq and makak. I’m a reactionary.

M: What are you, Rashif?

I’m tired. Tired of being the duckling amongst the cygnets.

The cygnet amongst the ducklings.

The pleb amongst the patricians.

M: You’re well spoken, for a foreigner

I try my best.

(…)

Once upon a time there was a boy. A boy who did not want to hurt anyone. When he still wore small clothes, the boy couldn’t stop crying. Seas of salty tears splashed and seeped from his eyes. But why did the boy cry? Where did all this sadness come from?

What was it that made him cry? “Nothing”, said the boy. The boy cried about nothing.

He cried about nothing and everything at the same time. He cried about the trees. He cried about the wind. He cried about the kitchen cabinet that hung on one hinge.

What nobody knew was that the boy was a barrel. A bottomless barrel that could hold all the sadness in the world. A barrel that could never be full. Every day, the boy absorbed the dampness of despair like a sponge. And every day, the boy would wring out the rag. Much to the regret of everyone around him. So, what was wrong? What was making him cry? Big boys don’t cry.

The boy’s clothes got bigger and one day he came to a decision. He would never hurt anyone. Maybe that would stop the crying. If he slipped through life like a phantom.

Without snapping a twig underfoot. Without harming a fly. Without ever really being there. Maybe then that would stop the crying. If he could rid himself of it, then the crying would definitely stop. Never laying a finger on anyone. Always keeping his distance. Everything the boy did was considered. Calculated carefully. Always thinking three steps ahead. He wanted to leave the world behind as if he had never been there.

So that, in the end, it would seem like he never was. Without hurting anyone. Without leaving any scars. Without upsetting the karmic balance. This is how the boy decided to live. That’s how the boy built up his walls. That’s how he shut the floodgates. Piling up sandbags against the sea of sorrow that flooded him daily.

And as if by magic, his hard work started to pay off. And as his eyes dried, his skin became tougher than chestnut bark. As his clothes grew, the boy learned to live. But he was only pretending.

(…)

I always say I don’t have negative associations with being half-Moroccan anymore.

But when I think about it, why wouldn’t I have any negative associations?

What I’m trying to say is, even though the problems with my father had nothing to do with him being Moroccan, he was the first Moroccan I knew.

My father’s family never kept in touch. They never asked how we were doing. My godfather Hassan doesn’t want any contact with me right now because “I know how he feels about all that”. I was eight when I last saw him in the flesh… As if I would have any fucking idea how he feels about it.

The Moroccan friends I had as a teenager either tried to convert me, or refused to see me as a true Moroccan. I’m too scared to say anything in Darija because those words don’t feel like mine.

Because I know I will be corrected anyway. Because I know I don’t fit in.

(…)

I’ve never had a beach holiday in Morocco. I still don’t know how to make a good tagine. I don’t know how Iftar is supposed to feel during Ramadan.

And still I tell myself I have no negative associations with Morocco.

Even though Belgium keeps telling me I should.

I’ve heard all the insults.

I’ve heard their judgey tone.

I’ve heard all about their good intentions.

I know that when it comes to random police checks I am always randomly chosen. I know I have to ask my mother to call for me when I want to rent a house. Because her name is Adriaens, and mine is El Kaoui.

I know I can’t get into clubs, even if I’m wearing leather shoes. Unless it’s an R&B night.

If I had to describe every time the outside world reminded me of my Moroccan-ness

in a negative way, we’d be here all night.

And still I have no negative associations with Morocco…And I’m not sure why anymore…

I don’t know whose footsteps I’m following in. I don’t know what foundations I’ve built my identity on. I’m neither fish nor fowl.

Maybe I’m a racist myself.

(…)

The village in the Atlas mountains. On the way there, I died roughly four times a minute inside my head. The route along the paved mountain road took such razor-sharp turns that I saw an oncoming vehicle behind every bend, which could drive us off the road and plunge us into the abyss below.

We met my uncle Abdelkarim’s cousin-in-law in some kind of cafe/post office/rest stop/restaurant at the end of the known world. It made me think of a Moroccan version of the cantina from Star Wars. We’re nearly there, said the cousin. Just a few more miles to Tingliane. It’s just a tad off-road.

If I died roughly four times a minute on the previous road, then I found myself in a constant state of near-death during those last few miles. The route was no longer paved, and barely wide enough for two scrawny donkeys to ride side-by-side. Our interpreter Mustapha’s white-knuckled grip on the steering wheel was a little too tight for my liking. Even though he himself was from the mountains.

An hour and a half later we arrive in Tingliane. And yeah, sure enough, plenty of sand and goats.

But also a sky that shimmers. Undulating sand in a thousand shades of red. Air that anoints the lungs.

Old men look at me and say my father’s name, “Hammid”, before Mustapha has even translated a single word.

We eat at the cousin’s house. A dozen men from the village have been invited. They are all distant relatives or old acquaintances of my grandfather. Did I know that my grandfather dug the village well? Did I know my grandfather responsible for the track we’d driven along? Did I know my grandfather built the mosque? Did I know there were only 3 families who had a say in village affairs, and that the El Kaouis were one of them? Did I know my father came back here once or twice as an adult? With- who was it again? Ah yes, Peter, yes, Peter who bathed in the reservoir that held the village’s drinking water.

He chased a wild boar once. Halouf. I only knew that Halouf was haram.

(…)

I spent that night tossing and turning.

Outside my window is a donkey, who’s half-hourly braying makes his existence known to the world.

Ahmet is sleeping in the room next to me. What I learnt that night was that when Ahmet is really tired, he snores louder than a donkey who wants the whole world to know of its existence.

And I haven’t even mentioned the rustling, buzzing, and fluttering in the dark.

I only made one mistake that night.

And that was using the torch on my phone to light up the room.

Bad idea. Let’s just say that I didn’t know that locusts could get that big.

I get it. I don’t belong in this village. That’s obvious.

Ahmet and I tower like giants above everyone else in the village, thanks to the dash of Celtic DNA thrown into the cauldron of our conception.

I don’t speak the language. I can only nod to a few of the men and repeat a word every now and then.

This village was trapped in a bell jar of time.

This village was frozen in time.

It fights against the time rushing by on the other end of the mountain path only wide enough for those two donkeys. And yet, I’m beginning to understand.

(…)

My father’s gravestone is at the end of the churchyard, next to the jardin du souvenir, the garden of rest. I walk down the red pebbled pathway to the marble wall. Ahmet and Alex trail behind me. And it feels strange, almost staged. The gravel grinds under my feet. Everything feels forced and theatrical, like some sort of morbid performance.

I stop at the gravestone. The Pyrenees rise up around the village. I had expected to see a photo next to the stone. I had expected to see him here again.

But it’s just a memorial plaque. Ahmed El Kaoui 1959-2012. Finished with wrought iron.

I don’t know how I’m supposed to feel. I’ve travelled thousands of miles, to Morocco, to France, thousands of miles to the depths of my soul to finally be standing here. And I feel frustration, fury. Delphine told me that he said: “Rashif will come to me eventually, when he’s ready.” And I’m angry with him. I’ve travelled all this way, and have never been able to let go of my past, my rage. And still, I can’t find the right place to get it off my chest. Not even at this stone.

I smoke a cigarette. And afterwards I retreat to a corner of the churchyard, amongst a few conifers.

Suddenly a small ginger cat comes up to me. It walks right up and rubs against my leg.

It lies down and lets me stroke it. That’s when something within me broke.

I went back to the grave and wept. For the first time since I became an El Kaoui I wept for him. I wept over the weight of it all. All the words I hide behind.

All the philosophical contemplation. Everything fell away.

It was as simple as “Dad didn’t want to be around me”. “Dad wanted to leave.” Dad couldn’t be a dad. Because of his sorrows that he tried to drown. Because of his childhood. So simple. Yet so sad. Desperately sad.

My father never left the mountains of his youth.

My father was still that child running in the mountains.

Cut out of the picture. Trapped in a tableau that wasn’t his.

He couldn’t become a man in the village.

Nor could he become a man in Belgium.

He found his freedoms in hippie culture: liberation, free love, drink and drugs… in order to cope.

To rebel against his father, who had already decided his children’s destiny.

But my father couldn’t go back.

(…)

For me, the personal is political. I prefer not to speak in absolutes, but I would even say that the personal is always political.

I’m probably being too preachy again. That’s always the criticism directed at ‘ethnic’ theatre. It is often said that art is not political. Do black and brown creators always have to focus on social issues?

That’s what I hear from the crowds and the critics. Can’t it just be about love? About the beauty of things? About art? I mean… there’s nothing I’d like more…but it cannot be. For once, I’d like to do a Shakespeare but right now it just can’t be. What am I saying? I’ve tried it: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. I only played Nick. I wore a beige suit and played the part just as Albee had written it. First review after the performance: kudos to them for adding a racial angle to that Nick character.

So, I wrote something. And yes, it’s spoken word. A bastard’s speech. Let me get my soap box. Tom, can you switch off the mic? Speeches work better unplugged…

SCENE 37: BEGIN SPEECH / LIGHTS ON.

Camera on. Rashif’s mic off!

If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

*Who recognises this one?

-Shakespeare- The Merchant of Venice.

Ask yourself the question: do I question myself?

How carefully do you question yourself?

Turn to the past, there lies your future.

Walk with us along the trail of tears.

And count the vertebrae of the broken backs busted

by the burden of your prosperity.

Don’t feel guilty. And don’t take pity. But look. Look around you.

Slit your veins open with the scalpel of self-analysis.

Slice open your veins with this scalpel. Make the cut vertically. Not horizontally like a cry for help, quickly stemmed with a cloth for the bleeding.

Make the cut vertically.

So the bile can flow out. Past the point of no return. Take a good look around you.

Your perspective is tinted. In sepia, black and white. Who chose the colour filter?

But don’t feel guilty. That only leads to white tears. And white tears are not milk. Tears are too salty for children to suckle.

This is the age of the bastard. A flexible time of fluidity, fusion, and flooding.

A time in which too much is too meagre. An era of uncertainty.

Listen. Listen. To the voices unheard. The voices stifled before they could be heard, stifled in the womb, an unfortunate by-product of our ‘idyllic’ society.

We are bastards. Neither half nor double bloods. We are children of Horus. Children of the moon. Children of Kal-El. We bleed in silence. Drip by drip. Drop by drop. That one drop is all they ever see.

Look beyond the phenotypes and realise that there’s only one human race. With many tribes. Race is a social construct. Tribal is trivial.

Lies are stories with power. Lies are stories from power.

We make a journey au bout de la nuit, through the night. Helter Skelter style. The wormwood star shines from the high heavens.

We’re mixed-up, but don’t get it twisted.

We are hybrid exotics. Tempting. Forbidden fruits willingly picked. Not quite dangerous enough to bite, but still…Des petits fétiches to indulge your desires.

Go on. Tickle it, take it.

You may well be woke-washed, but deep down there’s blood on your hands.

When we’re older everyone will be beige. And that is neither a goal, nor a problem. Bastards are the children of tomorrow. And we don’t ask for much. But what we do ask is a lot and that’s only that you question yourself.

Dare to ask. Ask so that we exist. Dare to ask, but we’re not your teacher.