Rebel with a Cause: Father Damien on Molokai

On 11 October 2009, the Flemish missionary, known as Father Damien, was declared a saint by Pope Benedict XVI. Father Damien (1840-1889) became known worldwide for his extraordinary service in caring for the lepers on the Hawaiian island of Molokai in the 19th Century. His greatest achievement was the development of a progressive microcosmos in world of the exiled and the dying.

`You’re not to call Damien “Father”.’ That’s what the young Flemish priest, Father Valentin Vranckx, was told when he arrived in Honolulu shortly after the death of Damien de Veuster. ‘Just “Damien” will do.’

For the local superiors of the Picpus Order were convinced that ‘Father’ was not a suitable title for Damien. They looked down on him. Indeed, they despised him. True, the Bishop of Honolulu, Hermann Köckemann, felt obliged to give him a laudatory funeral oration, which he delivered during a requiem Mass in Honolulu Cathedral. But after that, the De Veuster business was over and done with as far as he was concerned.

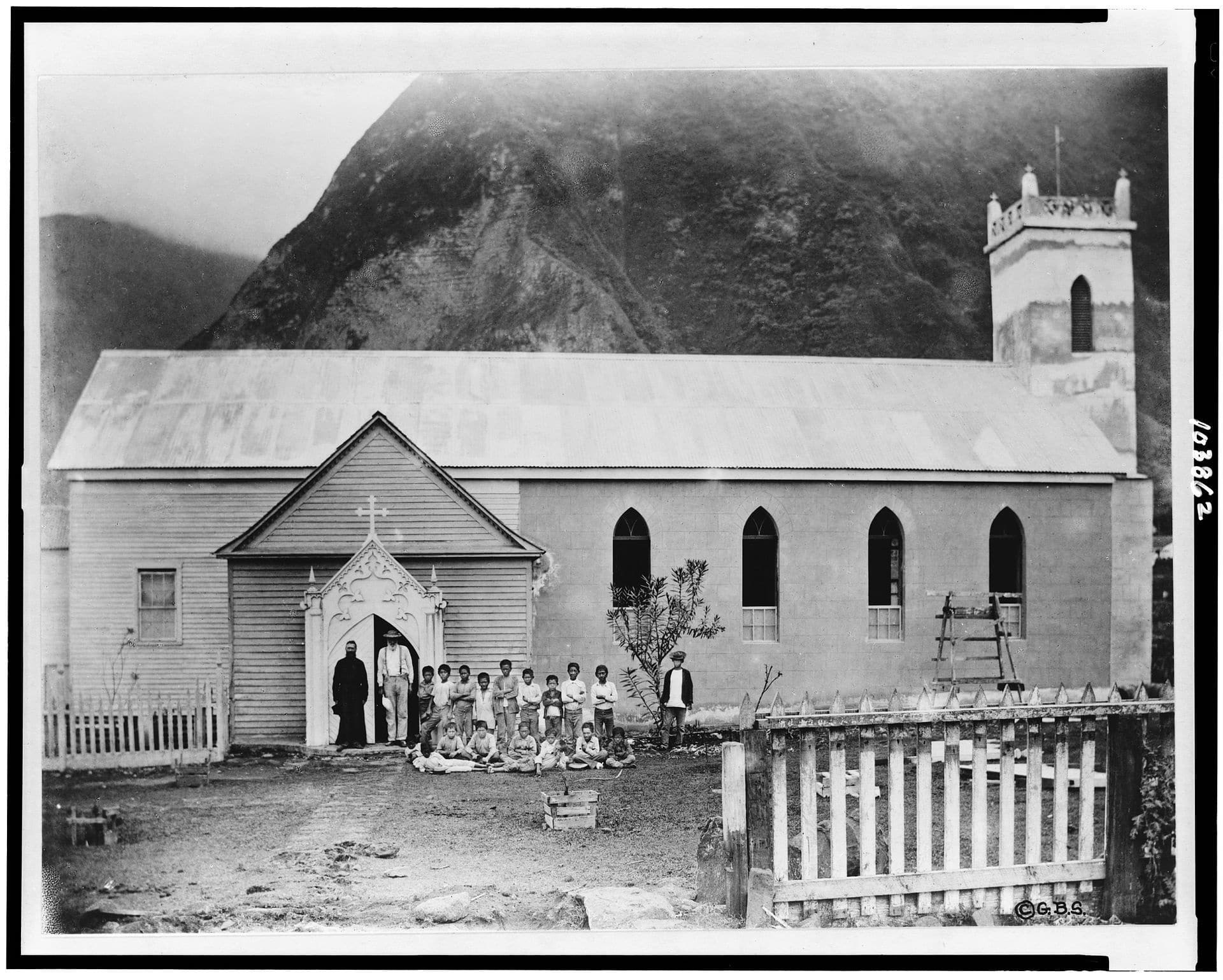

Father Damien in 1873, the year he went to Molokai.

Father Damien in 1873, the year he went to Molokai.© Wikipedia

Shortly after his ordination as bishop, Köckemann had had an encounter with Damien that deeply shocked him. His Grace would make only one visit to Damien in the leper colony at Molokai. The bishop, who was deathly afraid of illness, especially leprosy, saw it as his duty to personally deliver the decoration that had been awarded to Damien by the regent, Princess Liliuokalani. It was a hellish journey. Terrified of heights, the bishop had to climb down a six-hundred metre cliff by creeping along the precipice on an unprotected path. Damien practically had to carry him. That was bad enough, for the bishop feared even then (and rightly so, it later turned out) that De Veuster himself had leprosy. But the worst was not the sickness or the phobia. It was the fact that Damien had introduced the Protestant minister and his deacons as ‘Brothers in Christ’. To the conservative bishop, this phrase rang in his ears like heresy.

That had taken place in 1881. That year, in fact, saw the beginning of Damien’s descent into hell, of which the whole world would gradually become aware. Despite all the hostility, the vicious little objections, the open quarrels, the renunciations, the conflicts and particularly the loneliness, Damien persevered. And that is what made him great.

In 1883, Bishop Köckemann chose Leonor Fouesnel as provincial head of the Order for the Hawaiian archipelago. This French priest also held Damien in utter contempt. The motivating force was jealousy, which had been generated on the day Damien volunteered for a mission on Molokai. That day Fouesnel’s new church in Wailuku on the island of Maui had been dedicated. The church was a perfect gem, though the financing of its construction had completely drained the mission’s treasury.

During the festivities that followed the church’s consecration the old bishop Louis Maigret, a liberal, had asked for a volunteer to do a three-month stint with the lepers. Damien and three other priests were eager to go, and Damien happened to be first in line. In the days that followed, Fouesnel hoped to receive a splendid press file containing glowing reports of his church, but all he got were a few short bits. Damien’s ‘sacrifice’ had seized everyone’s attention. Fouesnel developed a scalding hatred for the Flemish `peasant’ and would plague and taunt Damien until his death.

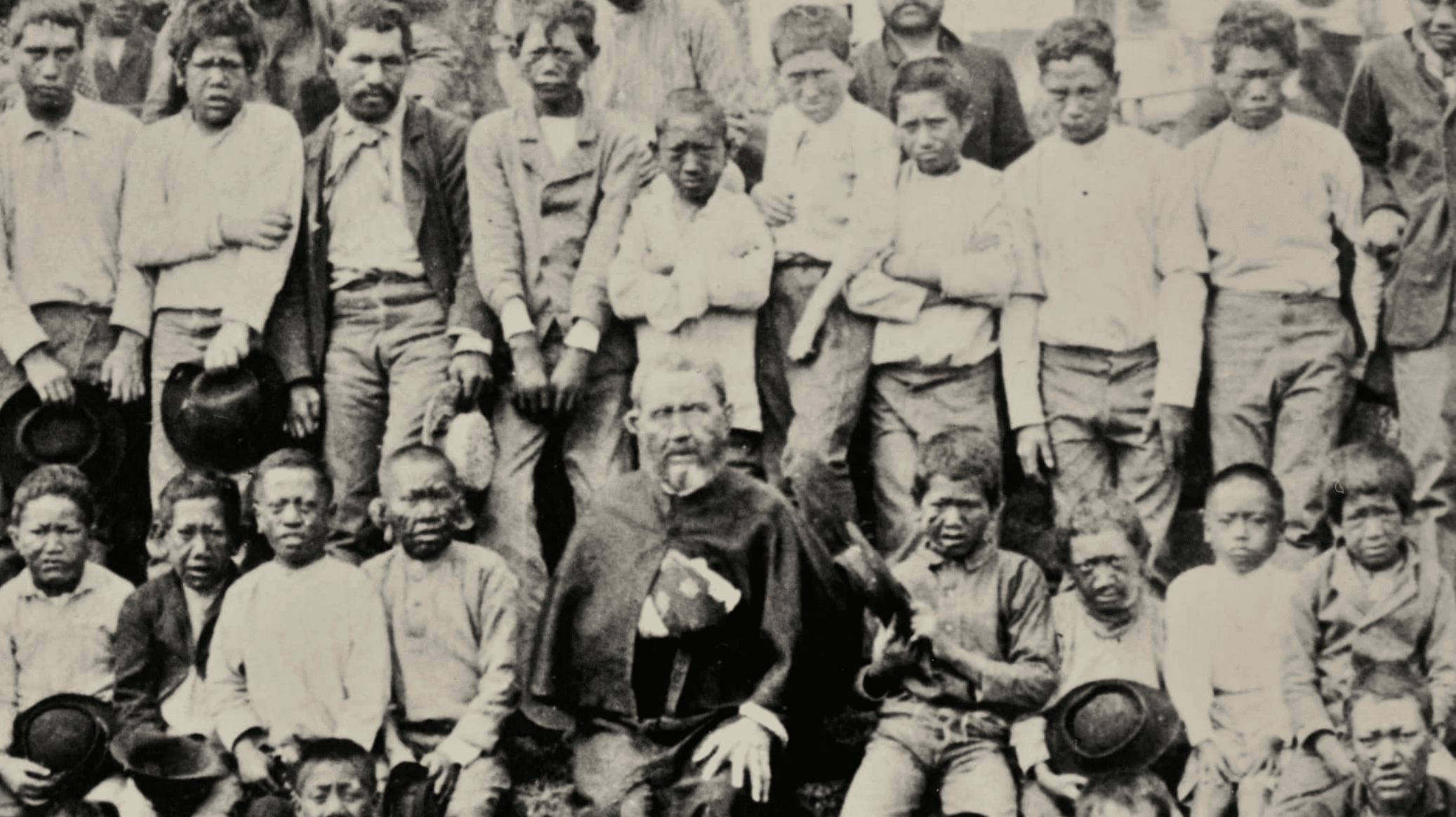

Father Damien, seen here with the Kalawao Girls Choir during the 1870s.

Father Damien, seen here with the Kalawao Girls Choir during the 1870s.© Wikipedia

Fighting for nurses

The more famous Damien became, the more his superiors turned against him. And new elements kept cropping up that could be used as weapons in the battle. Shortly after Fouesnel was appointed provincial head, the Franciscan sisters arrived on the Hawaiian islands. The King had invited them to care for the sick, and the Hawaiian government would assume all costs. But Fouesnel, who was sent to the United States to look for nursing sisters, had made a different proposition to the Franciscan Superiors. Because no volunteers were forthcoming, Fouesnel narrowed his invitation to ‘for curable illnesses’. In doing so, he excluded Molokai, which was a segregated place for incurable lepers.

As soon as he arrived in 1873, Damien knew that the patients’ biggest need was nursing. Doctors were useful but not necessary, since there was no cure for the disease. But people who would work day in and day out washing wounds, administering cough syrup, handing out medicine for diarrhoea — these were what the sick needed.

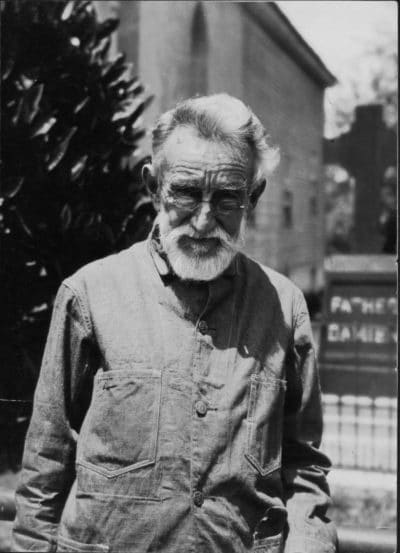

Father Damien in front of a church, image taken between ca.1870 and 1889

Father Damien in front of a church, image taken between ca.1870 and 1889© Wikipedia

Damien had pleaded for nurses for ten years. The King had responded to his cry for help, and when the coming of the nursing sisters was announced he thought his dream had come true. But the dream collapsed even before their arrival. Shortly before they landed Fouesnel categorically forbade him to have any contact with them. Their task was to care for those who were not yet confirmed cases, later the white lepers and a few other lucky ones would be added. Damien would have to care for the hopeless cases, dumped on Molokai, himself. Nevertheless, Damien refused to take this lying down; he continued to ask for nurses and after a while he turned to other congregations.

Thus the situation on Molokai, the second-class establishment, became intolerable. In Kaka’ako the sisters cared for a hundred patients that had been declared curable or were regarded as mild cases. There was one nurse for every ten patients, two doctors on the staff and visiting doctors for those who could afford it. The Boo lepers on Molokai had Damien, a doctor who came by only sporadically and, after 1886, a non-professional nurse. This disturbed Damien’s sense of justice; still, some years later, in 1888, he would win his cause.

Damien had another dream: an ordinary existence for his lepers. He wanted his patients to live ‘normal’ lives, and that meant parties, marriages, good food, clothing, washing and, most of all, nursing care. He knew that he had little time left to create his model society. He had seen the way the disease ran its course with so many people, and he knew that when the ears began to elongate, the person had four or five years to live at the most. When the bridge of the nose collapsed, he or she had only two years; when the disease hit the lungs, the prognosis was one year. He knew the symptoms and saw in the mirror that the clock was ticking for him, too. He would have to fight hard and fast to win the battle.

His superiors learned in 1883 that he had been struck by leprosy. The attending physicians had reported this to Köckemann, who passed the news on to Fouesnel and perhaps to the newly arrived nursing sisters. For the superiors this meant that the sisters could certainly not go to Molokai; if they did, the Communion host would have to be placed on their tongues by leprous fingers. The risk of infection was too great. The sisters agreed. The superiors might have sent a healthy priest as well, but there were too few missionaries to go round.

They had an excuse, for Damien had a reputation for not getting along with the fellow priests sent to him by the Order. For six years, from 1874 to 1880, he waged war with Andre Burgerman, a Dutch Picpus priest. Each priest wanted the leper colony all to himself. Damien was victorious in the end, while Burgerman, the favourite of the jealous Fouesnel, was forced to leave. The Dutchman would never forgive Damien.

Now Damien was alone, and a new priest had to be sent to help him. Even before his consecration as bishop, Köckemann had decided (and this became his first official decision) to banish the French priest Albert Montiton to Molokai as a leper. Köckemann had been at loggerheads with Montiton for years, so he was glad to be rid of him. Montiton suffered from a skin disease that covered his entire body. The worst aspect of the disease was the itching, which plagued him day and night. His arrival at Molokai provided Damien with a companion, but the nursing sisters could not receive the host from him either. So no nurses came.

Father Damien amidst some of his leper patients

Father Damien amidst some of his leper patients© Arterra Picture Library/Alamy

Medical experiments

Jealousy, fear of leprosy, the struggle for nurses: these were a few of the areas of conflict. His superiors were also opposed to Damien’s medical experiments. It is not clear whether the idea for the testing method came from Dr Nathaniel Emerson or from Damien himself, but the fact is that in 1878 Damien and the physician conducted a scientific experiment using a method that was not in general use until much later. The Dominicans had given Damien a Chinese medicine called Hoang Nan which was said to cure itching and leprosy and to be effective as an antidote for snake and insect bites, but Damien wasn’t sure that the medicine actually worked. At night in the presbytery, the priest opened a series of capsules and filled them with similar-looking but neutral powder. Working at his table, he put together two test groups composed of the same sorts of patients: equal numbers of men and women, tuberculoid and lepromatous lepers, advanced and early cases. The one group were given the look-alike medicine, the other the real medicine. Initially there was visible improvement in both groups, but as time passed both groups declined with equal speed. Damien had placed his hope in Hoang Nan, but once again the attempt was futile. Damien’s method would later be known as the placebo test.

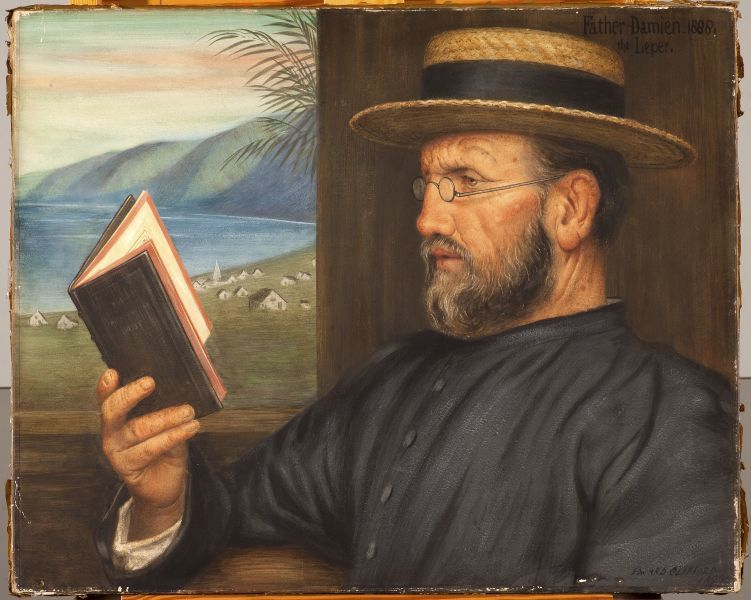

Portrait of Father Damien by Edward Clifford

Portrait of Father Damien by Edward Clifford© collection Damiaancentrum, Leuven

Damien knew that he had to inspire hope, so he struggled to bring to Molokai the Japanese therapy that was being used in the hospital near Honolulu. This was a battle he would win, though it became a new source of irritation for his superiors. In retrospect, the method turned out to be nothing more than an improvement in hygiene, whereby a whole series of side effects, such as festering wounds, were eliminated. But it was not a cure.

There were other things about Damien that troubled his superiors. His openness to different ways of thinking became a weapon that they used in the increasingly fierce battle. Damien did not stick to the prevailing conservative manual. Not only did he call Protestants ‘Brothers in Christ’, but he took alms that had been donated by Catholics and gave them to Protestants. When Catholics came to him who did not attend Mass every Sunday, who were living together – who were, in short, ‘bad’ Catholics – he gave them what they needed. Damien followed a different set of principles. He looked for needs and alleviated them, without betraying his own calling.

`Things should not transpire,’ was the motto that was applied in the leper colony. The fact that Protestants and Mormons participated in the sacramental procession was kept carefully hidden. This openness would later be called ecumenism, though at that time it was not based on any official theory. It just happened.

Care of the dying

His plea for care of the dying was not appreciated by either his superiors or the government of Walter M. Gibson. Damien argued that lepers should be allowed to marry. This gave the mission an enormous number of administrative problems, because Damien had to ask the priest of the parish to which the sick person had formerly belonged if the marriage candidate was free to marry. The overworked priest often ignored the request until he had the time to answer it. Missionaries often served from six to ten churches, and that meant that the registries of all those churches had to be consulted. On top of that, the marriage candidate might have been married by another rite or by civil ceremony. It was a difficult job, so the request often went unanswered. Secondly, did dying people have to marry at all? The conservative wing was of the opinion that it would be better to run the leper colony like a hospital, with a wall between the men’s and women’s wards.

Damien would have none of this. He ended up marrying someone on his death bed. He had waited and waited for an answer, but none came. The bridegroom kept his promise: he remained faithful to his wife for three days, and then he died. And Damien found himself in hot water; he had not been patient. According to the bishop, he should have waited for an answer before blessing the marriage of a possibly married man.

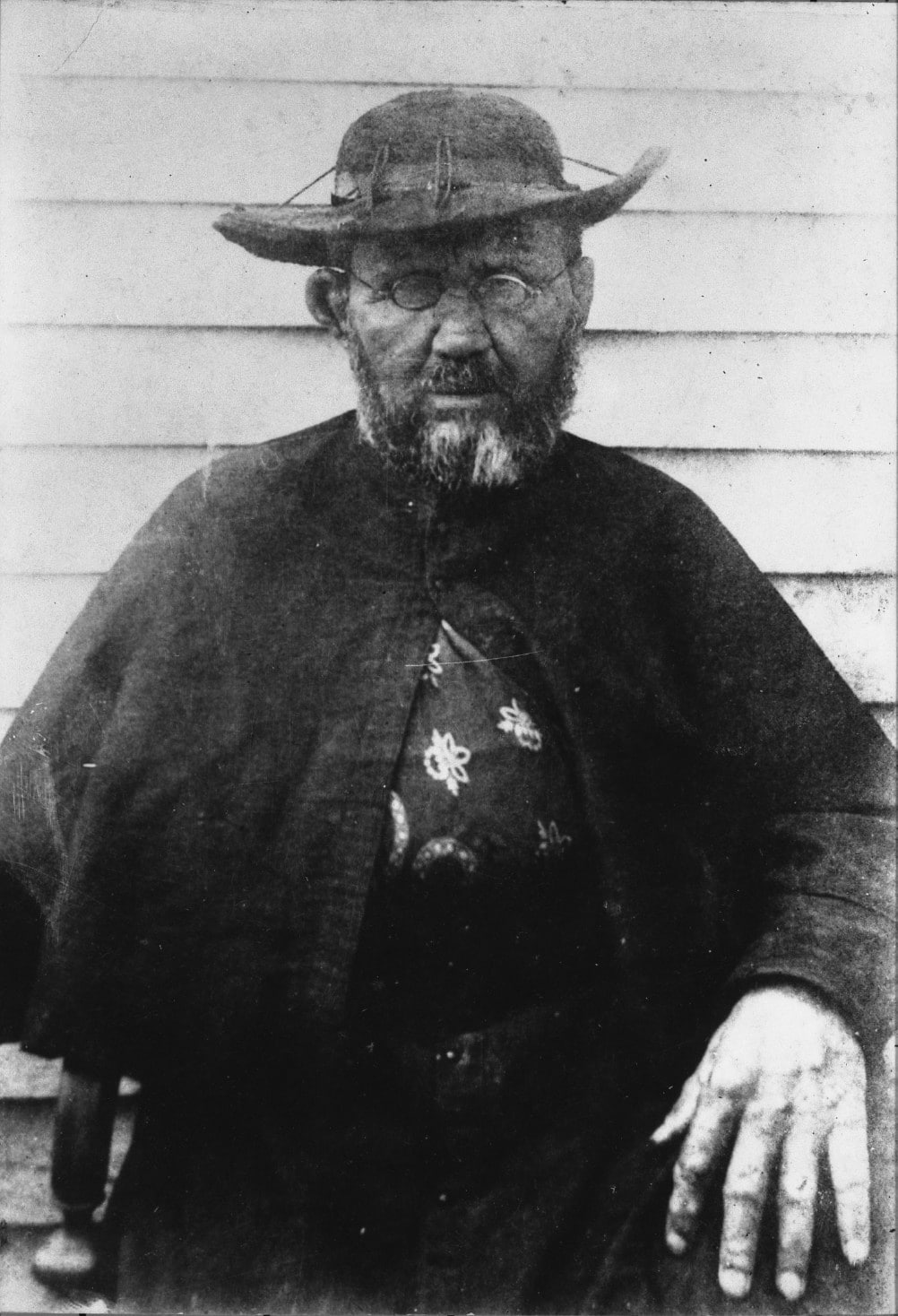

Father Damien, taken in 1889, weeks before his death by William Brigham at a side wall of the St. Philomena Catholic Church on the settlement.

Father Damien, taken in 1889, weeks before his death by William Brigham at a side wall of the St. Philomena Catholic Church on the settlement.© Wikipedia

Damien fought for a normal existence for his patients. They had to be able to participate in daily life. He refused to treat them like hospital numbers; he threw parties for them, told jokes, held musical events and organised burial societies, so that even those who really had no one were not alone.

In his fight for more clothing, better food, better housing conditions, and especially for nursing care and attendance, he told story after story of how the disease evolved in people who had the support of a loved one: a parent, a child, a wife, a husband, a friend. They developed fewer secondary symptoms, and the direct symptoms they exhibited were less severe. They simply bore the disease better. Opposing all the politicians, Damien attempted to lessen the insistence on segregation.

Damien knew what he was talking about, because as the disease advanced fewer and fewer priests came by to hear his confession, which the rule obliged him to make each month. Sometimes he had to wait six months for a visit of a few hours.

He fought for a companion, and when his superiors refused he took matters into his own hands and insisted that the Belgian priest Louis-Lambert Conrardy, a secular missionary, be allowed to join him. After a turbulent series of conflicts, Conrardy arrived less than a year before Damien’s death. It required a constant struggle for his friend to be allowed to stay, but Damien persevered and in the end he did not die alone.

Damien’s plea for care for the sick and dying has a very modern ring to it. He did not develop any complicated theories. His attitude was based on worldly wisdom and years of observation and experience. Later, what he argued for would be given the name ‘palliative care’.

In 1886, when Damien had been at the leper colony for thirteen years, the situation erupted into a genuine conflict. Damien was hardly ever visited by his brother priests. The Franciscans, who had already been on the island for three years, had not once been to Molokai. He had no companion and his illness was taking its toll. He lost his eyebrows. The bridge of his nose began to give way. Worst of all, he feared that after his death all his work would collapse.

Damien was given permission by the Board of Health to visit the leper hospital near Honolulu, but his superiors forbade him to go. After all, he might contaminate the chasuble and the chalice. Other feeble reasons were adduced. But Damien wanted care for his lepers, and he needed the support of his fellow priests, so he left for Honolulu. His intention was to study Japanese bath therapy and adapt it to Molokai.

The trip was a triumph. Even the King visited him in the leper hospital. Both the government and his superiors knew that they had to do something for Damien, to make some kind of public gesture, and the Prime Minister solemnly promised to install bath therapy on Molokai. A retired quarter-master in the American army came knocking on the door of the mission shortly after Damien’s ten-day visit. He wanted to volunteer his services to the lepers and was appointed companion – not a priest, but a penitent.

Joseph Dutton near Damien’s grave at St. Philomena Church, Kalawao

Joseph Dutton near Damien’s grave at St. Philomena Church, Kalawao© Wikipedia

Joseph Ira Dutton was the retired officer’ s name. During the American Civil War it had been his job to take care of supplies. He knew how to organise things, and he was able to convince Damien to let him draw up an explicit proposal for the construction of the hospital that had been promised by the King and the Prime Minister. He persuaded Damien to write three begging letters within a period of two days, actually the only three straightforward appeals that the priest would write. Damien wrote to the General of the Picpus Order, to an American priest connected with Notre Dame University, and to an Anglican vicar from Peckham near London. It was his response to their friendly offers to do something for him.

The Order sent a few gifts, significant but not sizeable. The American priest had some huge shrines built, which later would provoke a great fuss from Fouesnel. But it was the English Anglican vicar who collected the largest sum. His generosity would get Damien back into hot water with his superiors.

Three weeks after Prime Minister Gibson flatly refused to install the bath therapy at Molokai, Damien received £1,000 from Great Britain, the first of a series of cheques. Suddenly Damien was rich. He immediately began looking for some gift that he could give to every single patient, Catholic or not, married or not, to make them happy. He settled on clothing, a new outfit for everybody.

His superiors were outraged. Damien was supposed to give the money to them. Buying clothing was an insult to the government, so the government was outraged and proposed in a commanding tone that Damien hand over the donation. Damien stubbornly continued to deposit the sums he received in the leper fund. He copied and signed every proposal for a last will and testament that the superiors sent him, but he kept the money until his death. His plan was to underwrite the bath therapy himself, even if it was seen as a slap in the face for the Prime Minister.

The struggle with religious and secular authorities had entered its final phase. Money, jealousy, fear: these negative feelings all served to inflame the controversy.

Five months after the first donation arrived from London, Hawaii’s white Protestants staged a successful coup against Gibson and he was forced to leave the islands. The new Prime Minister, Lorrin Thurston, pursued a different policy. He appointed Damien’s friend, Dr Nathaniel Emerson, as the new chairman of the Board of Health. Emerson knew about leprosy. As a physician he realised how essential nursing care was, and he began to push the idea immediately. He would eventually succeed in his efforts and bring the nursing sisters to Molokai.

The sisters landed in mid-November 1888. Damien died in April 1889. He had won his battle for nursing care. He died surrounded by lay helpers and supported by his friend Conrardy. His superiors were relieved; the difficult man was finally out of their hair.

Original grave of Father Damien next to the St. Philomena Roman Catholic Church in Kalawao, Kalaupapa Peninsula, Molokaʻi, Hawaii

Original grave of Father Damien next to the St. Philomena Roman Catholic Church in Kalawao, Kalaupapa Peninsula, Molokaʻi, Hawaii© Wikipedia

Canonisation

The superiors were wrong. After his death, Damien became, if not more famous, then certainly more important. In London, the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, gave a funeral oration that went far beyond Bishop Köckemann’s homily. The Prince wanted to use Damien to promote the battle against leprosy, and he succeeded. The British and American benefactors who had given so generously continued to honour the priest.

The General of the Picpus Order immediately began an investigation to prepare for canonisation, but had to abandon his efforts because of the total opposition from the Hawaiian superiors. Köckemann and Fouesnel hoped that all the commotion would die out quietly. But they miscalculated, especially after Robert Louis Stevenson, in response to an attack on Damien by a Protestant minister, wrote a small book about him.

The book was as sharp as it was brief. Stevenson turned all the criticism of Damien into accolades. The book circulated around the world and was a great success. The Hawaiian superiors were now forced to sing the praises of the man whom they had despised.

The only thing they succeeded in doing was boycotting the beatification process. The first attempt, which took place around the turn of the century, came to naught. A second investigation was launched in the year 1930. The transfer of Damien’s remains to Belgium, against his express wish, was part of this. This time the Second World War put an end to the investigation.

Damien had two weak points in his dossier. He was a man ahead of his time, and therefore regarded as ‘disobedient’ to his local superiors. This called his vow of obedience into question. And no miracles had been attributed to him. It was the late Mother Theresa who broke the impasse in this case. Damien’s life, she argued, was a miracle in itself. So the beatification took place by Pope John Paul II in Rome on 4 June 1995. Upon his beatification, Blessed Damien was granted a memorial feast day, which is celebrated on 10 May. Father Damien was canonised by Pope Benedict XVI on 11 October 2009.

A fellow sufferer

The fact is that Damien de Veuster was an extraordinary man, who regrettably is often depicted as a not very clever individual. He had a university diploma, but he belonged to the liberal-Catholic faction during his student years. He was also a passionate man. Once he was in the leper colony, nothing existed for him but the patients. He did everything for them, even unusual things that at the time were considered taboo. This aroused the hatred of frightened people who preferred everything to be orderly and predictable.

Even before Damien’s death the American writer Charles Stoddard wrote a best-seller about him. He was a famous man in his time and, like Mother Theresa, he was regarded as a living saint, which provoked a great deal of jealousy. He received many donations, but he died in the only shirt he had to his name. Until a few days before his death, he (who had fought for beds for his patients) slept on a mat on the ground. He had kept his vow of poverty.

The truth is that all the testimonies of people who knew him well emphasise his joy. They speak of his sense of humour, his positive attitude. This may be why he has become such a well-known Fleming, with his statue in the Capitol in Washington D.C. as a great American. After all, he was a solitary fighter, an unconventional thinker, who could be happy despite all opposition and misery. When he was dying, he called himself ‘the happiest of missionaries’, and he signed the letter ‘Father Damien’, because he was in truth a father for his people. Apart from the religious context, it was an honorary title he richly deserved.

The article was previously published in our yearbook The Low Countries, № 6, 1998.