Hospitality, to an Extent. Refugees in the Netherlands

At the beginning of the First World War, one million Belgians fled to the Netherlands. About one hundred thousand remained there throughout the war, most of them in large camps. The Netherlands showed itself to be hospitable, but there was much to be said about the conditions in the refugee camps. What remains of those shelters after more than a century? And how is it going with the refugees in the Netherlands today? “More so than the Afghans, Ukrainians now are more similar to Belgian refugees back then.”

From an ancient village,

– camel brown as the steppe –

from Plocka,

came Dinska Bronska.

Her kerchief was Prussian-blue

and her hair flax-yellow;

also her eyes were blue

like fjord water.

She smelt of garlic and spruce,

she wore boots

and went very heavy and fast.

At the “Hotel Lapland” she sat

at a table by the street window

she was writing a letter.

A lock of hair fell low on her red jaw

and she stuck out her tongue,

because she wrote that letter with difficulty

and underneath it “Dinska Bronska”, her name.

She also stuck the pen stick in her mouth

and searched with her eyes along the ceiling.

On the paper was ‘an inkblot

and large stumping of letters:

she bought it for ten centimes

in the grocery shop

across the hotel.

There was a little ink on her jaw.

Oh, Dinska Bronska;

thou art leaving for Canada:

the rusty steamer waits along the quay.

Thou read on an almanack

of the “Red Star Line”

that Canada has greater apples,

oh, higher and yellower corn than Plocka.

It must be much better in Canada!

Oh, Dinska Bronska,

with your very fat fingers:

you write that letter so hard.

Your eyes search flies on the ceiling.

“Moj Boze!”

There’s a tear-sweep,

oh so sad,

from your blue eyes to your mouth.

Oh, Dinska Bronska!

In Flemish literature, no more beautiful ode to the displaced exists than ‘Dinska Bronska’ by Karel Van den Oever (1879-1926), a writer who was born, raised and died in Antwerp. If his name is still remembered amongst literature lovers today, it is thanks to this melancholy elegy to the homeless who, whilst awaiting their embarkation to the Promised Land, were regular customers in the Van den Oevers Antwerp shop.

It could be called ironic that Van den Oever – a contemporary of Willem Elsschot and Marnix Gijsen – found his place in the footnotes of Flemish literary history with this poem for the emigrants. In his writing the man expressed a typical chauvinism with regard not only to his hometown, but if possible, even to the specific neighborhood where he was born. The Dutch writer Jeroen Brouwers writes about Van den Oever that: “Antwerp sat around him like a coat that he never took off, unless with the greatest reluctance.” A trip to Ghent with the Antwerp literary circle around the magazine Alvoorder results no sooner in a rapturous verse full of nostalgia for his hometown.

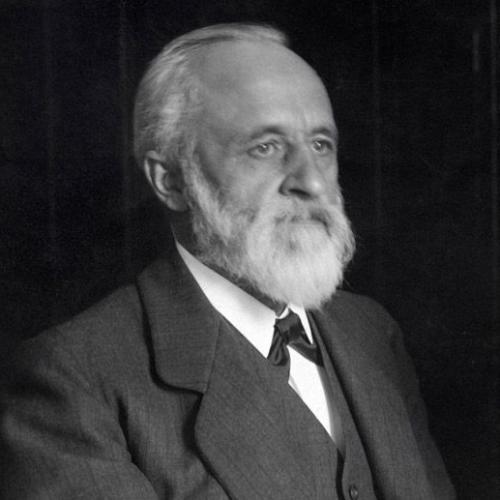

Karel Van den Oever

Karel Van den Oeverimage via Neerlandistiek.nl

At the same time, it is no coincidence that this poet so deeply devoted to Antwerp is also able to paint such a sensitive portrait of the displaced. During the First World War, Van den Oever together with nearly one million other Belgian refugees crossed the border into the Netherlands. The thoroughbred Antwerp resident ends up in genteel Baarn (near Hilversum), extremely unhappy amid such extremely Dutch affairs, as can be read in his Verzen uitt oorlogstijd (Wartime Verses, 1919).

But all it takes is a cursory read of Frans Verachtert’s monograph to find that, despite his four-year exile, Van den Oever didn’t get off so badly in his country house in Baarn. The hundreds of thousands of Belgians who rushed across the border in those first few months after the hostilities began found themselves in decidedly less comfortable conditions. Their all too often forgotten story is one that we want to reconstruct here, and mirror with the present.

'Extraordinary burdens'

4 August, 1914. After the Belgian government rejects the German ultimatum for free passage, Germany invades Belgium. Many Belgians immediately flee to the Netherlands by train, on horseback, or on foot – with or without a wheelbarrow to haul their most prized possessions.

The neutral Netherlands is hospitable. Refugees are received en masse by citizens and support committees who provide money and clothing. In border municipalities, temporary shelter is found in empty customs houses, factory buildings, schools, churches, barns, and stables. The Dutch Minister of the Interior, the liberal democrat Pieter Cort van der Linden, soon announces that “unsalaried refugees” will be financed “at government expense”. Together with the Minister of War he establishes a central commission for the protection of refugees who have emigrated to the Netherlands. It will not only register all Belgian refugees in the Netherlands but will also look for their housing.

Queen Wilhelmina and Princess Juliana in 1914

Queen Wilhelmina and Princess Juliana in 1914© Royal Library, The Hague

This Dutch hospitality is also reflected in Queen Wilhelmina’s speech from the throne on 15 September. “Deeply committed to the fate of all peoples who have been dragged into the war,” said the Queen, “the Netherlands willingly bears the extraordinary burdens imposed on it and welcomes with open arms all the unfortunate who seek refuge within its borders.”

After the fall of Antwerp at the beginning of October 1914, the number of Belgian refugees in the Netherlands reaches its peak: more than one million Belgians have made the crossing. That is a lot, given that the Netherlands then counted only 6.24 million inhabitants. Chaos ensues, and there is far too little housing. Private individuals who offer shelter to refugees are now entitled to an allowance.

After negotiations with the German occupier, the mayor of Antwerp and several aldermen publish an appeal to all Belgians in the Netherlands on 15 October in various Dutch newspapers: everyone can safely return to their homeland. The Minister of the Interior Cort van der Linden also calls on mayors to exert gentle coercion on the Belgian refugees, so that they might return home.

Many Belgians heed the call, but not all refugees believe the German’s promises and guarantees. In December of 1914, there are still 200,000 Belgian refugees in the Netherlands. On 1 May, 1915 there are still 105,000. It is now clear that they will remain in the Netherlands for a longer period.

The hospitality and generosity of private individuals gradually declines, and public buildings, which house many refugees, must be restored to their original function. This gives rise to the idea of concentrating all refugees present in the Netherlands in refugee camps. The largest camps are built in Amersfoort, Ede, Nunspeet and Uden (more on this later), but Belgian refugees also reside in Hontenisse, Bergen op Zoom, Gouda, and other locations – whether temporarily or otherwise.

Belgian refugees in Arnhem, 1914

Belgian refugees in Arnhem, 1914© Gelders Archief

Beer-loving women

More than one century later, we take a road trip through the Netherlands in search of what remains of the Belgian refugee camps. It is a Sunday morning in March, 2022. Just past Ede we park the car along the N-road towards Arnhem. The Eder Heide is gray and grim. The cold wind, which whips here freely, cuts straight through our scarves.

At first glance, this part of the Veluwe seems like any other: sand, heath and – in the distance – smatterings of forest. It did not used to be this way, as shown by two boulders stacked on top of each other. The modest monument contains a placard with the inscription: ‘BELGIAN REFUGEE CAMP 1914-1918. THIS STONE IN EDE REMINDS US OF THE PAST.”

Nearby we find a sign with a map of the Ede refugee camp. The accompanying text is barely legible, but the camp must have been gigantic. 5,300 Belgians spent a large part of the First World War in this camp on the Eder Hei, and there was even capacity for nearly twice as many.

The Belgian memorial in Ede

The Belgian memorial in Ede© Wikimedia Commons

More than one hundred years ago, the Dutch government chose this location for two reasons: there was enough space, and the Ede-Wageningen station was nearby. In January 1915, the first Belgian refugees arrived at that station by train. In the snow and hail, they began the hike to the refuge. At first glance it must have looked like a penal colony: between the 153 wooden barracks spread out across the heath stood knee-high bales of hay. In the barracks, the refugees would have to sleep on straw sacks.

And yet compared to other Dutch refuges from that time, Ede was seen as a model camp. There were three residential blocks in the camp – the Scheldedorp, the Maasdorp and the Leyedorp – with dormitories, dining rooms, and washrooms. The camp also had a hospital, a church, a post office, a bathhouse, a theatre, sports facilities, and schools. There was even central heating and electricity. Heating in the dormitories was a luxury that many houses in nearby Ede did not even have. Thanks to a fundraiser in Denmark, at some point the camp was even expanded to include family homes – the so-called “Danish village”.

It was not all peace and tranquillity between the Belgian Catholic refugees and the orthodox Ede locals

But it was not all peace and tranquillity between the Belgian Catholic refugees and the orthodox Ede locals – today, the conservative Calvinist SGP and the ChristenUnie

(Christian Union) are still the largest parties in the Ede city council. Belgian women found drinking beer in the village after finishing their shopping were watched in horror. On Sunday, curious Ede residents could even come and take a look at the camp for a fee.

The refugees would not be allowed to stay in the Ede refugee camp until the end of the war. Establishing the state budget for 1917, the Dutch House of Representatives debated the abolition of the camp. Why? Austerity. One member of Parliament, Frederik Willem Nicolaas Hugenholtz of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party, was incensed when the liberal interior minister Cort van der Linden suggests that the Ede refuge provides a life of luxury. Hugenholtz: “We speak of those well-known wooden villages in which people are shabbily housed, which of course cannot be helped. But surely there can be no question of overspending here?”

Cort van der Linden was prime minister during the First World War

Cort van der Linden was prime minister during the First World War© Time graphics

As an austerity measure, Cort van der Linden had previously decided to turn off the heating in the dormitories. Shortly thereafter in December 1916, seventeen Belgian camp children died of measles – before then it had been only three per month. “It would hardly be surprising if, especially in the event of a measles epidemic, the severe cold in these wooden sheds would have an adverse effect on the chances for these small patients to live,” says Social Democrat Hugenholtz.

But the minister stands firm: in May 1917, he closes the Ede refugee camp. The remaining 3,000 refugees are transferred to Nunspeet, even deeper in the Veluwe, into even worse conditions.

Pillars of the community

During the First World War, the Netherlands was confronted for the first time on a national scale with large numbers of refugees – so explains Leo Lucassen, director of the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam and specialist in the history of migration and integration. “Initially, shelter was left largely to private initiatives: to the Catholic Church, to organizations such as the housing committee in Den Bosch, and to local authorities. But it soon became clear that the state itself had to do something too.”

Belgian refugees certainly sensitized the Netherlands to issues of migration, says Lucassen, but in a rather negative way: they see it as something you should try to prevent. “After an initial period of hospitable reception, the central government quickly started to say that the Belgians had to go back. The government also believed that the civil society with which the refugees felt most connected should be responsible for their reception – in the case of the Belgians, that would be the Catholic church.”

Leo Lucassen: 'Belgian refugees sensitized the Netherlands to issues of migration, but in a rather negative way'

According to Lucassen, who is also affiliated with Leiden University as a historian, this principle was clearly seen again when another large influx of refugees reached the Netherlands in the 1930s: the Jewish Germans. “Back then, the Dutch government was much more restrictive. The position was that the Dutch-Jewish community should take care of them. Camp Westerbork, later a transit camp, was originally used to receive Jewish refugees in the Netherlands. Its construction was financed by the Jewish community.”

Even more so than on refugee policy, Belgian refugees left their mark on the Dutch labour market. Until the First World War, foreign migrant labourers in the Netherlands faced little to no barriers. But this was changed by the arrival of tens of thousands of male Belgian refugees who offered themselves on the Dutch labour market at cheaper rates. “In 1915, unions started complaining about violations of labour laws,” says Lucassen. “But the question is whether that was really the case: because of mobilization, there were serious labour shortages anyway.”

Even more so than on refugee policy, Belgian refugees left their mark on the Dutch labour market

Still, after the First World War the Dutch government suddenly drew boundaries between its own workers and foreign workers. “In addition to the Belgians, this also had to do with the changing role of the central government in the welfare state,” says Lucassen. “The state declared itself more or less a guarantor, taking over unemployment benefits that had previously been managed by unions.”

Amersfoort, 'capital of the Belgians'

More than thirty thousand soldiers also fled to the Netherlands. Because the Netherlands was neutral, it was mandatory for the country to take in migrant soldiers according to the 1907 Convention in The Hague. That happened in Amersfoort, among other cities, where today there stands a monument to the Belgians. And so it should: it is the largest war memorial on Dutch soil, says tour guide Jan Niessen at the second stop on our road trip.

Amersfoort became known as a ‘Belgian capital’ during the First World War: no fewer than 19,000 refugees found a home there after the outbreak of the hostilities in Belgium. This solution was hardly self-evident – the city had been struck by floods as recently as 1914. But the nearly 25,000 inhabitants of Amersfoort saw the population of their city nearly double.

Belgian refugees introduced novelties to Dutch cuisine such as the inevitable fries.

Belgian refugees introduced novelties to Dutch cuisine such as the inevitable fries.© Gelders Archief

Integration was not without a struggle. As early as 1914, there was an initial uprising in Amersfoort. The Marechaussee opened fire and eight Belgian soldiers died. Both the Belgian and Dutch parliaments condemned the drama. Painter Rik Wouters, who died in the Netherlands in 1916, dedicated a painting to the shooting – he, too, lived in Amersfoort. Socialist leaders Camille Huysmans and Pieter Jelles Troelstra wanted to investigate the situation on the spot, but they were denied permission. The military commanders did not want visitation from socialists.

After the shooting incident, however, the rules were relaxed: refugees were allowed to work, they were allowed to enter the city without a uniform, and were considered to be equal to the local population.

Within the camp there arose several villages with names like ‘Albert’s village’ and ‘Elisabeth’s village’ after the then Belgian royal couple. Women and children on the one hand and men on the other were housed in separate villages. The wooden houses were designed in such a way that they could be moved, and each village grew into temporary communities with their own churches and schools. Funding for the humanitarian project came from the Swedish and Danish governments and from the religious Quaker movement, among others.

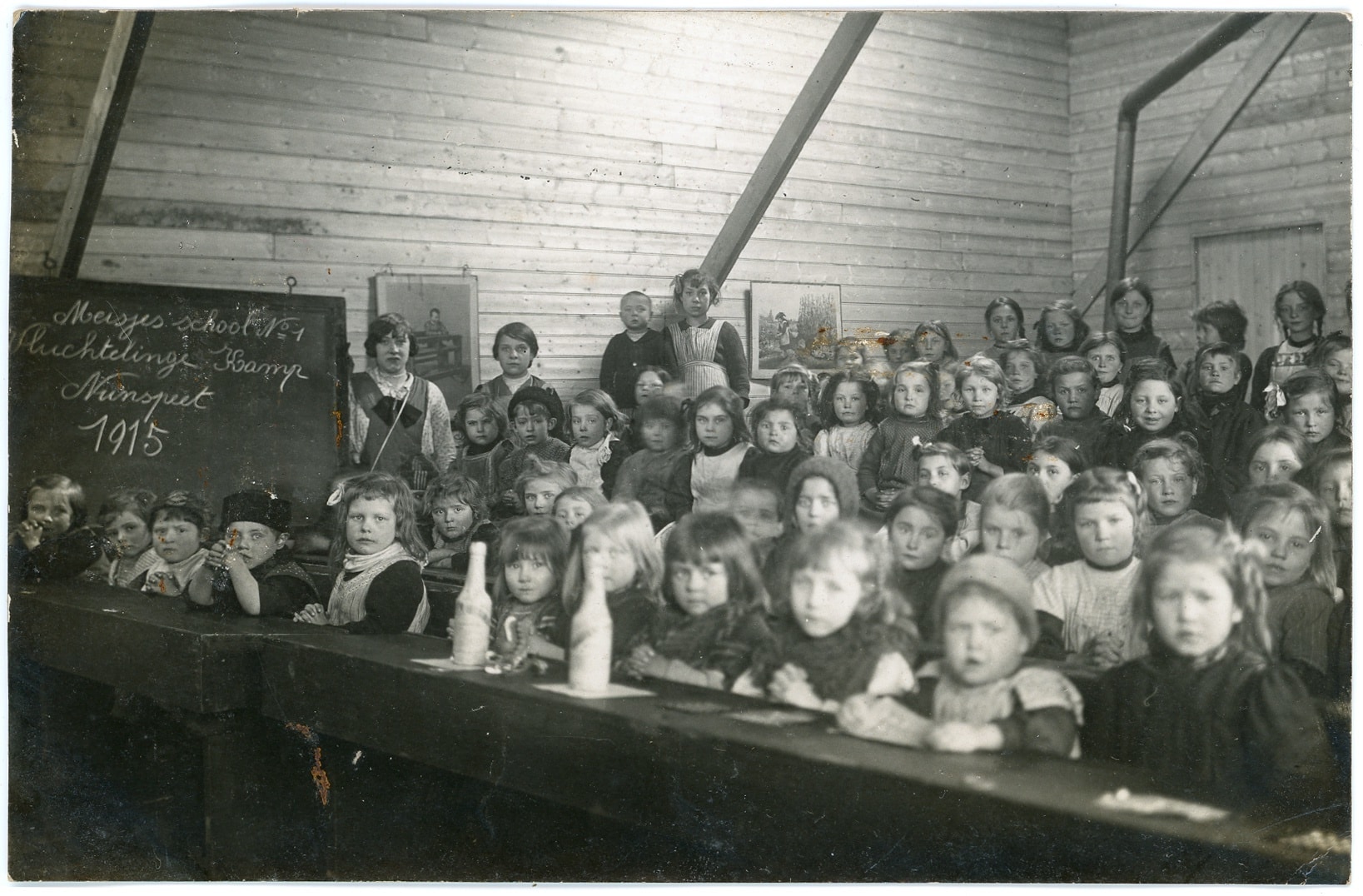

A girls' class at the Nunspeet camp, 1915

A girls' class at the Nunspeet camp, 1915© Gelders Archief

Education pioneer Omer Buysse organized education (both vocational and technical) for the Belgians, most of whom were farmers’ sons, many of them illiterate. Training them in exile to become skilled workers prevented the boredom of camp life, and moreover after the war masses of workers would be needed for reconstruction. A separate ‘university’ was established for the officers.

Belgians would not be Belgians if they had been thrilled by the Dutch food in the camp. They called the Dutch pea soup, for example, beton armé, and themselves introduced novelties in Dutch cuisine such as tomato soup and the inevitable fries.

Today, little of the camp remains. The areas that were still heath in 1914 are now largely wooded. There is, however, a large monument at the highest point in Amersfoort (a ‘mountain’ 44 meters above sea level), designed by the well-known architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage. At the bottom of the ‘mountain’ you pass a bas-relief depicting the horrors of the war. Atop, another relief has been applied to the monument in the same style in which the swords have been reforged into plows; in which life is good again. The one Belgian passer-by we meet compares the reliefs, with a sense of historical irony, to Soviet art.

The Belgian Memorial

The Belgian Memorial© Wikipedia

The construction of this Belgian monument started during the war and was completed in 1917, though it would not be solemnly inaugurated until 1938 in the presence of Leopold III. Why was the inauguration delayed by twenty years? The war had not yet ended, but Belgium and the Netherlands were already at odds. In 1918, independent Belgium, not yet 100 years old, saw the end of the war as its chance to reclaim Zeelandic Flanders and Dutch Limburg, disputed areas that it had given up to the Dutch in 1839. Belgium argues that despite its so-called neutrality, the Netherlands allowed the Germans to retreat through its territory. The Netherlands, on the other hand, ask Belgium to foot the bill for their years-long reception of Belgian refugees – a practice that was, incidentally, supported by international law at the time.

It was not until 1938 that the turbidity sufficiently cooled, and the Belgian king came to inaugurate the Belgian monument.

'Flanders Avenue', Nunspeet

Nunspeet, in the middle of the Veluwe: A residential area near Eperweg bears names like Elisabeth Avenue, Albert Avenue, and Leopold Avenue. There is a Boudewijn Park, a Fabiola Avenue, and even a Paolo Avenue, a Flanders Avenue, and a Kempen Avenue. This is, of course, no coincidence: here too, on the third stop of our road trip, a Belgian refugee camp was once located.

At the nearby Nunspeet-Oost cemetery we look for traces of that camp, but in vain: after fifteen minutes we still have not found a single grave bearing Belgian names. Just as we are about to give up, we come across an elderly man clearing the final resting place of his loved one. Does he know where the graves of the Belgian refugees are? “Not here, at least”, he says in a typical Veluws dialect. He advises us to look through the Old Cemetery, a few hundred meters away, nearer to the center of Nunspeet.

The grave of toddler Philips Polak. In early 1915, there was a high infant mortality rate at the Nunspeet camp.

The grave of toddler Philips Polak. In early 1915, there was a high infant mortality rate at the Nunspeet camp.© Michiel Leen

The cast iron gate of the Old Cemetery creaks open. At the entrance, a map shows us where the Belgian refugees are buried. Two hundred and fifty stone crosses rise above the freshly mowed lawn. These are graves of Belgian children who died from contagious diseases in the camps, as in the measles epidemic. The place is impressive, even more so in these times of geopolitical tension and huge refugee flows. Only one childhood grave bears a name: that of a certain Philips Polak born on 21 April, 1912 in Antwerp. He died less than three years later on 17 February, 1915 in Nunspeet.

A small stone monument has been built at the edge of the cemetery. The words on the monument leave little to the imagination. O CRUX, AVE SPES UNICA, it says, a Latin expression that amounts to: greetings to the cross, our only hope. And below that: The Hospitable Netherlands. To the PERISHED REFUGEES. 1914-1919.

Damp and drafty

On 24 November, 1914, the newspaper Provinciale Overrijsselsche and Zwolsche Courant writes that the Nunspeet refugee camp is nearing completion. It is a few hectares in size and comprises sixty-two buildings. Here, too, rest and relaxation for the refugees has been considered, including for example a football field. It will be the only camp to house refugees for the entirety of the war.

Lesser subjects in particular are relocated to this Nunspeet camp. Those refugees who cannot provide for themselves live together here. “In view of the danger posed to our public health and morality by the presence in our country of female refugees with loose morals”, Minister Cort van der Linden reports that all “public women” among the refugees, women who “enter openly into dealings with men” must be transferred without delay, and if necessary against their will, to the Nunspeet refugee camp.

The conditions are poor from the very start. Already on 9 December, 1914, Het Volk writes: “People have to sleep on loose straw, which is spread directly on the earth or on slats. It is damp and drafty there.” The Burgundian Belgians complain about the quantity and quality of the food and about the ferrous drinking water which makes many people sick. There is no freedom of movement. The camp is enclosed with a double row of barbed wire and is militarily guarded. No one is allowed to pass beyond the barbed wire. The refugees are treated as prisoners.

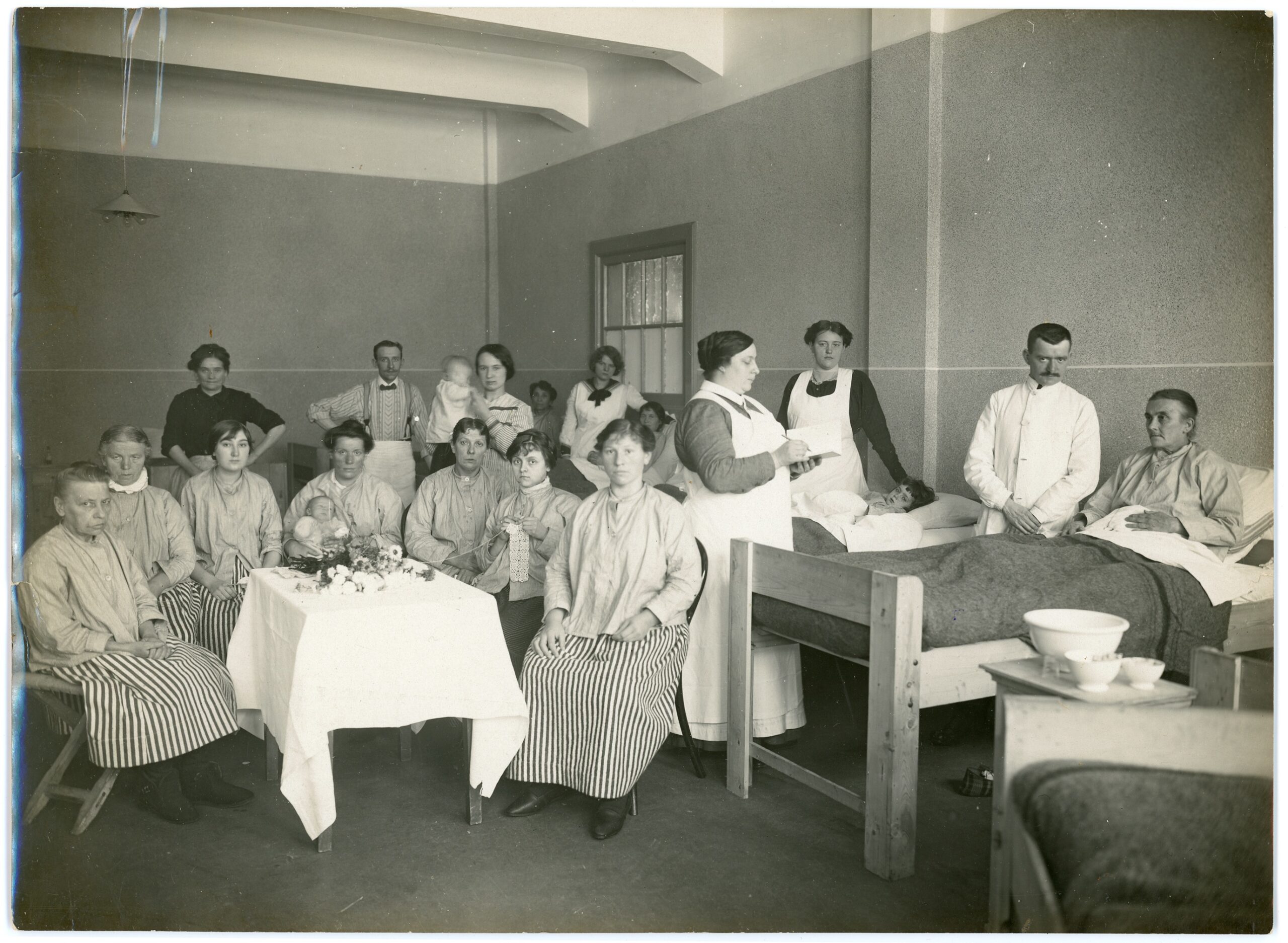

Because the sleeping and eating sheds were insufficiently heated many people fell sick, especially among the children.

Because the sleeping and eating sheds were insufficiently heated many people fell sick, especially among the children.© Gelders Archief

Because the sleeping and eating sheds are insufficiently heated many people fall sick, especially among the children. Care for these patients leaves much to be desired. Ten nurses do what they can, but it is not enough. One woman who gives birth is left without care for six hours and dies shortly thereafter. And for infants, there is not nearly enough milk or porridge.

The greatest disaster comes at the beginning of 1915. “The high infant mortality rate, which was observed in the Nunspeet refugee camp in December and at the beginning of January, has attracted a great deal of attention,” writes De Telegraaf. “2, 3, sometimes 4 children die each day. It is no wonder, then, that all kinds of rumors are circulating and that the Nunspeet camp nurses have come to stand in a poor light. […] The high mortality rate – for which official figures are not yet available – started in the first week of January.” Today, a field of slowly rusting crosses is the deathly silent witness to that chaos.

Industrial area Vluchtoord

Besides Ede and Nunspeet there were many other refugee camps in the Netherlands, like in Bergen op Zoom or Uden in Brabant. At its peak, the latter town, not far from Den Bosch, was home to 7,020 refugees, more than the local population itself.

On the site where the Uden refugee camp once stood there is now a business park, appropriately named Vluchtoord – Refuge Site. One hundred years after the war, the local historians’ group has mapped out a walk around the site. A chapel has also been rebuilt, where Belgian and Dutch flags fly side-by-side in brotherly union. In Uden, too, hardly any physical traces of the actual camp have survived besides the remains of a velodrome built by the Belgians in a nearby forested area. But the walking trail with many educational posters and historical images does provide the opportunity to get a relatively quick picture of what life in such a refugee camp must have looked like.

Afghans in flight

The idea of refugees in the Netherlands housed in large camps under appalling conditions sometimes feels like a relic from the past. But is it? In August 2021, after the withdrawal of Western troops from Afghanistan and the takeover by the Taliban, about two thousand Afghans fled to the Netherlands. One of them is Abdullah (his real name known to the editors). Together with his wife and children, he is admitted on a flight from Kabul to the Netherlands because he had collaborated with the European Union in Afghanistan.

In the Netherlands, Abdullah and his family are transferred to the emergency shelter in Heumensoord. The large, tented camp where one thousand Afghan refugees reside is located in a forest near Nijmegen. It is expressly intended as a temporary reception site for a few weeks at most, but it soon becomes clear they will be there for longer period of time.

Improvised housing poses many problems. “The biggest problem was the lack of privacy,” says Abdullah. “Families of less than six people had to share a tent with other families.” Compartments are set up in the tent using tarps, but they do not stop sound. “One crying baby could keep the whole tent awake at night,” Abdullah says. “And when there was a lot of wind or it rained hard, not only children but also adults were afraid that the roof of the tent would fly off. During my time in Heumensoord I slept badly. For a long time, it was also unclear how long we would have to stay in this emergency shelter, which caused a lot of stress.”

Abdullah on the improvised housing: 'The biggest problem was the lack of privacy'

Not only the refugees are dissatisfied with the conditions in which they have come to live. At the beginning of November, the Institute for Human Rights and the National Ombudsman visited the emergency shelter. They determined the tent camp unsuitable for long-term stays by refugees. Although the emergency shelter was only intended for a few weeks, it would be three months – until early December 2021 – before Abdullah was transferred to an asylum center elsewhere in the country. Now with a five-year residence permit to his name, he is awaiting the moment the Dutch government grants him a home.

Culturally hopeless

That Afghan refugees do not seem to be a priority for the Dutch government comes as no surprise to Leo Lucassen. “When it comes to identification with refugees, whether the regime that causes their flight poses a direct threat to the Netherlands plays a major role,” he says. “That is not the case for Afghan refugees. After 9/11, they were often portrayed as culturally hopeless, as people who would not be able to adapt.”

According to Lucassen, this is also reflected in Dutch refugee policy. “We now know that the Dutch government acted very bureaucratically and not very proactively when the Taliban took power in Afghanistan in the summer of 2021. Exceptions have only been made for Afghans who helped Dutch people, like interpreters and drivers.”

Meanwhile Belgian refugees during the First World War, Hungarian refugees in 1956, Bosnian refugees in the 1990s, and Ukrainian refugees today are seen as more welcome, according to Lucassen. “The number of Ukrainians in the Netherlands doesn’t even matter at all, because the conflict with Russia is seen as a common conflict,” Lucassen says. “In that respect, Ukrainians, more so than Afghans, are the most like Belgian refugees.”

Epilogue

During our road trip through the Belgian refugee camps in the spring of 2022, the first shocks of the conflict in Ukraine became tangible in the Low Countries. We noticed this in Arnhem, where we met a boy from Saudi Arabia one evening at a bar. For him, the war presented a win-win situation: whoever gains the upper hand, his country will profit from it.

In the meantime, initiatives have been launched across Europe for the reception of refugees. Initially there was a lot of talk of housing refugees in private homes, but it soon became clear that this would not be enough. By March 2022, 4 million Ukrainians had already fled the country, several tens of thousands of them to the Netherlands where there is already a major housing crisis. The idea of refugee villages is on the table, but organizations like Vluchtelingenwerk are not in favor because Ukrainians would then be excluded from society.

Many Ukrainian refugees in the Netherlands have ended up in “emergency shelters”. In Gelderland, for example, this concerns Het Buitencentrum in Overasselt, a holiday camp for students which has room for 130 refugees. Nijmegen has room for 270 Ukrainian refugees in cruise ships in the Waalhaven and – temporarily – for a few hundred refugees in the local sports hall. In mid-June, 43,198 Ukrainians use the Dutch emergency shelters; an unknown number are still housed with private individuals.

Emergency village for Ukrainian refugees in Antwerp

Emergency village for Ukrainian refugees in Antwerp© CAW

Antwerp now has its own refugee village on the Linkeroever. There is enough room for a small village that comprises emergency housing resembling movable construction site crates. Initially, 104 of these apartments are built, which in principle can be used by up to 600 residents for one year. But Mayor Bart De Wever notes that he does not think the village will be vacated that soon. Otherwise, this contemporary refuge has much in common with the locations we visited on our trip: streets with names inspired by the homeland of the war refugees. There will also be a school, a laundromat, a medical post, and childcare. And WiFi. At the end of May, more than one hundred Ukrainian refugees were already living there, out of a total of about 4,500 Ukrainians who have registered in Antwerp since the start of the conflict.

From this village on the Linkeroever you can see the watchtower of the Red Star Line Museum, the museum of (European) emigrants.

This article was made possible with the support of the Pascal Decroos Fund.