‘Revolusi’ Corrects the Dutch Colonial Self-Image of Indonesia

In Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World, David van Reybrouck documents the Dutch colonial involvement in the world’s largest archipelago from the early seventeenth century until independence in late 1949. Using his literary talent, the author combines historical research and journalistic reportage into a highly engaging story, writes deputy editor-in-chief Tomas Vanheste.

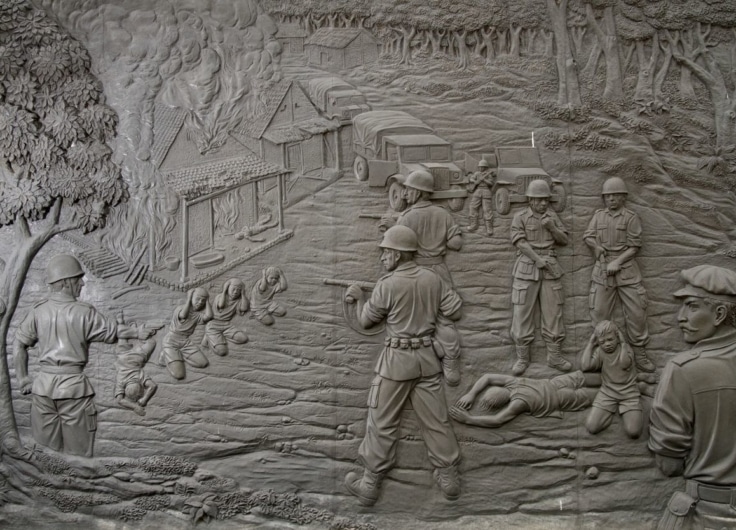

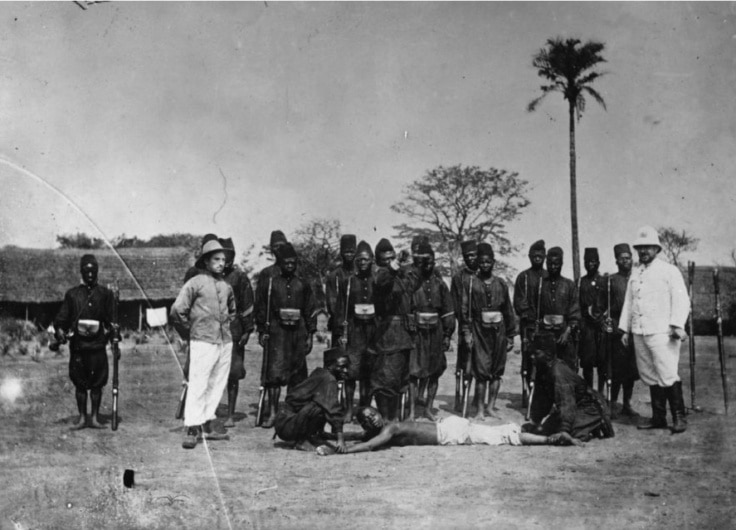

847.80 euros. In September 2020, a court in The Hague sentences the Dutch state to pay this compensation to the son of Abubakar Lambogo. Dutch soldiers had killed the resistance fighter from South Sulawesi, Indonesia, in March 1947 and impaled his head on a stake to scare the public. The son declined this meager compensation.

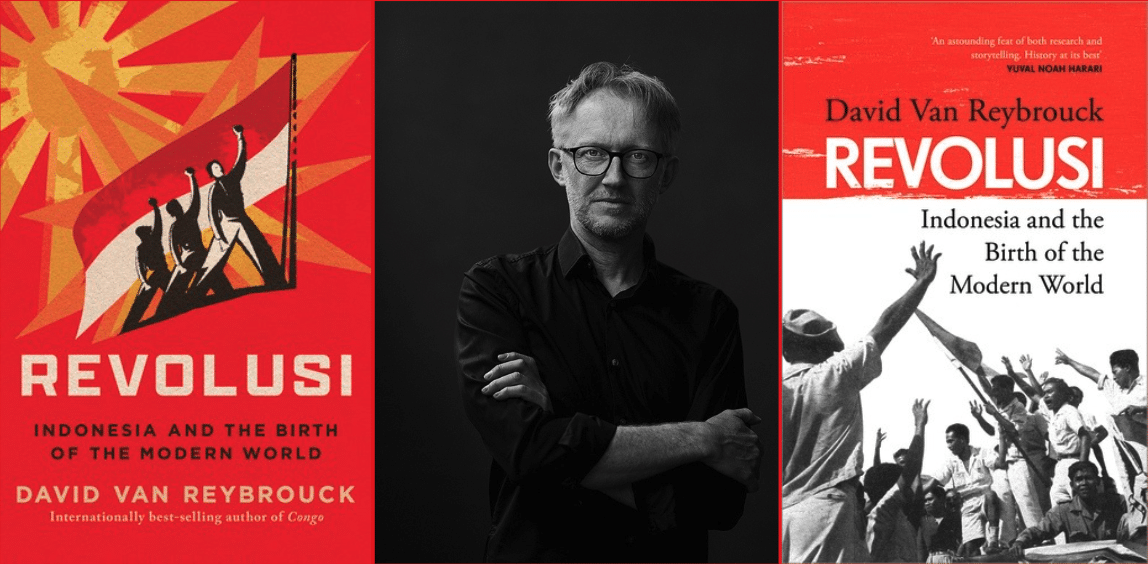

Raymond Westerling

Raymond Westerling© Dutch Ministry of Defence

The decapitation of Lambogo was part of a practice of summary executions and mass killings by the Dutch military. According to the notorious Captain Raymond Westerling, these actions were seen as the only way “to bring the island under control effectively, sustainable, and, most importantly, in a way that was morally justified.” The highest officials, writes David van Reybrouck in his book Revolusi, “knew very well that Westerling and his troops were acting illegally, but they allowed it because he achieved such excellent results, just as J.P. Coen did in the 1620s.”

Earlier in Revolusi, the author describes how the seafarer Coen, honored with a statue in Hoorn, exterminated the entire populations of the Banda Islands because they continued to supply nutmeg to companies other than the Dutch East India Company. Between ten and fifteen thousand people were killed. “Today, there is a word for this: genocide,” states van Reybrouck. He argues that historical relativism is not applicable here. This is not a case of different times, different morals. After all: “His methods were already subject to severe criticism at the time. His predecessor, Laurens Reael, criticized the use of all unjust and even barbaric methods that the VOC believed were necessary.”

With great precision, van Reybrouck shatters the Dutch self-image of a civilized country

Revolusi documents the Dutch colonial involvement in the world’s largest archipelago from the early seventeenth century until Indonesia’s independence at the end of 1949. As in Congo. The Epic History of a People, Van Reybrouck effectively combines historical research and journalistic reportage into a highly engaging story. Once again, he set out to speak with hundreds of eyewitnesses. He sat down with elders who had experienced the colonial era, the Japanese occupation, and the struggle for independence firsthand and listened to their stories. Their testimonies make this history particularly vivid and powerful, and often extraordinarily shocking.

With great precision, van Reybrouck shatters the Dutch self-image of a civilized country that, though swayed by colonial ideology for too long, like many other nations, still had the best interests of the population at heart.

The poffertjes moment

As in Congo, the oldest witness is a central figure. At a retirement home in Callantsoog in 2016, Van Reybrouck meets Djajeng Pratomo, born in 1914 in Sumatra. During their first meeting, a caregiver serves them poffertjes, small fluffy pancakes. “As I chewed on a slightly warm doughball, I realized that the Dutch colonial adventure was not driven by a desire for land, but by a craving for flavor,” writes van Reybrouck. The Netherlands did not invade an existing country to take it over; it initially did not claim any land and had no intention of taking control. They only wanted to extract something, particularly spices.”

With a freedom that an academic historian might not have but a writer does, he explains the Dutch push eastward. Just as Proust’s memories were triggered by the smell of a madeleine, Van Reybrouck’s insight was guided by the taste of poffertjes.

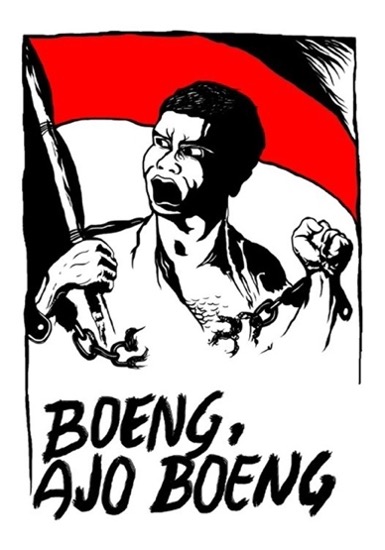

Poster designed by artist Raden Affandi from September 1945, urging the youth to fight for independence

Poster designed by artist Raden Affandi from September 1945, urging the youth to fight for independence© Wikipedia

In the 1930s, Pratomo became a member of the Perhimpoenan Indonesia (PI), the birthplace of Indonesian nationalism. He arrived in the Netherlands in 1936 to study. While he was studying economics in Rotterdam, World War II broke out. Like many other Indonesian students, he joined the resistance.

The colonized supported the colonizer in large numbers, writes van Reybrouck. It is estimated that one in tenth of the approximately eight hundred Indonesians in the Netherlands joined the resistance, a proportion that was many times higher than that of the Dutch population. Pratomo distributed resistance newspapers like Vrij Nederland in Rotterdam and also wrote pamphlets himself. In January 1973, the Sicherheitsdienst arrested him after his beloved Stennie, who was helping Jews go into hiding, was betrayed. He was sent to Camp Vught and later to Dachau.

In the 1930s, Pratomo became a member of the Perhimpoenan Indonesia (PI), the birthplace of Indonesian nationalism. He arrived in the Netherlands in 1936 to study. While he was studying economics in Rotterdam, World War II broke out. Like many other Indonesian students, he joined the resistance.

The colonized supported the colonizer in large numbers, writes van Reybrouck. It is estimated that one in tenth of the approximately eight hundred Indonesians in the Netherlands joined the resistance, a proportion that was many times higher than that of the Dutch population. Pratomo distributed resistance newspapers like Vrij Nederland in Rotterdam and also wrote pamphlets himself. In January 1973, the Sicherheitsdienst arrested him after his beloved Stennie, who was helping Jews go into hiding, was betrayed. He was sent to Camp Vught and later to Dachau.

There seems to be selective memory regarding the Japanese occupation of Indonesia

The role of the Indonesians in the anti-German resistance is largely unknown. “Since they later found themselves in conflict with the Dutch, their efforts in the resistance were erased from the national memory,” notes van Reybrouck.

There also seems to be selective memory regarding the Japanese occupation of Indonesia. By the end of World War II, an estimated five percent of the Javanese population had died of starvation, approximately 2.4 million people. However, Dutch collective memory has predominantly focused on the Japanese internment camps.

With a total of four million deaths, Indonesia was one of the countries hardest hit by the war. They died, writes van Reybrouck, “from hunger and deprivation in a military-economic clash between the Netherlands and Japan over the resource wealth of their land.”

For the oil

Indonesian oil was essential for the Japanese war machine. After the war, the Netherlands quickly sought to reclaim control over these resources. In magazine Indonesia, Djajeng Pratonomo and his colleagues from the independence movement wrote critical articles that pointed out painful truths: “The barrier of fascism has been removed, but we face new obstacles rooted in the same soil from which fascism grew: the self-interests of groups that benefit from keeping the masses powerless and limiting their rights. These are the major figures of the Indonesian plantations, tin, and oil industries…”

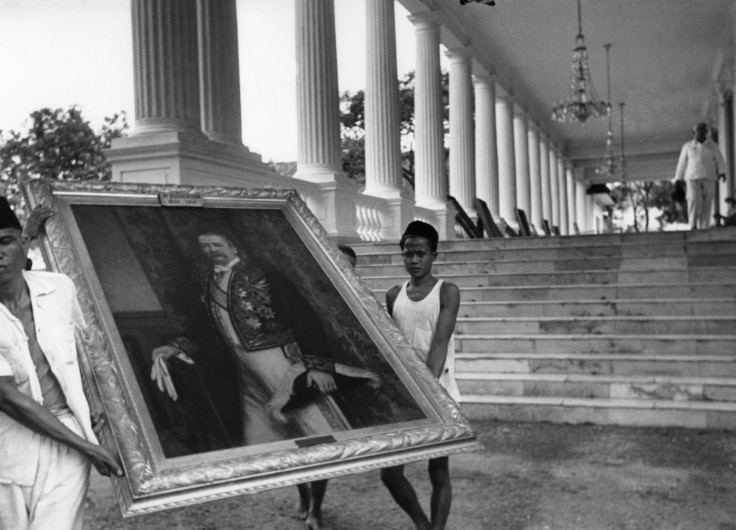

In the Netherlands, the general perception is that there were only two Police Actions. In reality, there was a war that lasted 52 months

What euphemistically entered history as the First Police Action in July 1947 was also driven by the desire to regain control over the plantations. The Netherlands sought to reclaim territories from the Republic of Indonesia, which had declared its independence on August 17, 1945. The country was in financial distress and urgently needed revenue from oil, tin, rubber, coffee, and other Indonesian primary goods. It quickly regained control over large areas. “The entrepreneurs could get back to work,” writes Van Reybrouck ironically. “The bankruptcy of the Netherlands and its overseas territory was temporarily averted.”

Between 1946 and 1949, a total of 120,000 conscript soldiers were sent to Indonesia to fight for the retention of the colony. Many of them did not wish to be involved in the occupation. The Dutch government continued to hunt for “deserters” until the late 1950s. They faced up to two years in prison. However, soldiers who committed war crimes in the colony went unpunished. Van Reybrouck concludes

The Netherlands wasted the rare opportunities for a peaceful agreement and dismissed the United Nations resolutions

In the Netherlands, the general perception is that there were only two Police Actions. In reality, van Reybrouck argues, there was a war that lasted 52 months until independence was achieved in December 1949. He meticulously maps out this period, and shows how the Netherlands wasted the rare opportunities for a peaceful agreement and dismissed the United Nations resolutions. Only when the United States threatened to suspend military aid under the newly established NATO did the Netherlands come to understand that independence was unavoidable.

But even then, it continued to prioritize its own financial interests. It ensured that all concessions made by Dutch enterprises were upheld and that Indonesia was required to take over all the debts of the Dutch East Indies. “In the same way that slaves in the nineteenth century had to pay their owners for their freedom, Indonesia too had to buy its own freedom,” Van Reybrouck critically analyzes.

Blatantly racist

In her speech at the sovereignty transfer, Queen Juliana spoke of “the deep sympathy between the two nations.” Revolusi reveals that this myth should be discarded. Van Reybrouck demonstrates that colonial society, particularly in the 1930s, was completely segregated and deeply entrenched in racism.

He illustrates this by using the image of the colonial packet boat, which was divided into three classes. At the highest level were the high-ranking Westerners, who enjoyed luxurious cabins with sinks, smoking rooms, and a private promenade deck with rattan chairs. The second level, with cabins closer to the noise of the engines and shared with strangers, was reserved for the less affluent Dutch and Indonesians who had acquired positions in the Dutch administration. On the lowest deck, people had just one and a half square meters for a mattrass and luggage. This was the only space available for the impoverished masses of ordinary Indonesians.

Your income and status in the colonial society depended on your skin color

Your income and status in the colonial society depended on your skin color. “The more pigment, the less payment.” Newspapers like Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlands-Indië openly expressed racist views about the population. “We believe that the Javenese is like a child: rebellious, unpredictable, troublesome, and lazy. Incapable of taking care of himself, incapable of doing any serious work independently.”

That attitude resulted in the Dutch receiving little sympathy from the oppressed population. Van Reybrouck includes many testimonies from people who did not see the Dutch as great friends. “Everyone hated the Dutch back then, including my parents. Simply because they took everything away,” says one of them.

Temporal colonialism

As he concludes his compelling history, the author does not simply organize his findings methodically. Instead, he praises Indonesia’s natural wealth and expresses his sadness over how quickly it has disappeared in a beautiful prologue. At the very end, he offers new insights by distinguishing between territorial and temporal colonialism. In the same way the Dutch colonized Indonesia, today’s generation affects future generations by destroying biodiversity and accelerating climate change.”

Yes, I’ve met the author a few times. I once interviewed him about his book on Congo for Vrij Nederland, and I’ve run into him occasionally since then. That might influence my judgment. No, I’m definitely not an expert in Indonesian history. This limits my ability to detect new details or spot potential flaws in his story. Even so, I firmly believe that David Van Reybrouck, with Revolusi, has written an exceptionally important book that calls for a serious reassessment of the Netherlands’ national self-image

David Van Reybrouck and the American and British edition of 'Revolusi'

David Van Reybrouck and the American and British edition of 'Revolusi'© Frank Ruiter

David Van Reybrouck, Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World, translated by David Colmer and David McKay, W.W. Norton & Company/New York, The Bodley Head/London, 2024, 656 pages

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.