Rijksmuseum Architect Pierre Cuypers was a Catholic Master Builder

The Rijksmuseum and the Central Station, Amsterdam’s two most iconic commissions were the work of a Catholic architect from Limburg, Pierre Cuypers. More representative for his oeuvre, however, are numerous churches, of which he designed more than one hundred. Cuypers made an active contribution to the emancipation of the Catholic church in the Netherlands. He was ‘an architect with a mission’.

‘Since they had put the roof in place, from his house Vedder could no longer see the wind sweeping over the IJ, but he could now read the direction of the wind on a dial that had been fixed to the west tower of the station building. Meanwhile, one after the other the most eloquent decorations appeared on the facades, explained and described in all manner of publications as the State of the Netherlands and represented on the topmost gable by the national coat of arms. Below this, the façade was graced by the city’s coat of arms, flanked by those of the fourteen cities to be linked to Amsterdam by rail. In the tympanums above the three windows of the meeting room, different peoples with their products paid homage to the maidenly personification of Amsterdam, enthroned in the central tympanum between the personifications of the IJ and the Amstel. The sculptures at the foot of the east tower symbolised, from left to right, ‘Agriculture’, ‘Livestock’ and ‘Trade’. And below that, in the form of a winged woman with a child, ‘Electricity’ – this at a time when the Electra electricity company was just starting to lay the first cables in the streets; when Carstens – referring to the worsening condition of his wife’s leg – began to press for a quick agreement, when spring was arriving and the first flounder were coming out of the Gouwzee.’

Amsterdam Central Station in 1895

Amsterdam Central Station in 1895© WikiImages via Pixabay

The description above is from the historical novel Public Works (Publieke Werken, 2000, pp. 205-206) by Thomas Rosenboom. The novel is set in late nineteenth-century Amsterdam, described in the context of the financial worries of the violin-maker Vedder, whose life is radically changed by the construction of the Central Station and a hotel to be built nearby. Through the eyes of Vedder, who can see the construction site from his house, the reader can observe the progress of the imposing new station. Pierre Cuypers was the architect who designed not only the building, but also the entire decorative scheme described in detail above.

Rijksmuseum in 1885, source: Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands

Rijksmuseum in 1885, source: Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands© Wikipedia

At almost the same time, the same architect built the Rijksmuseum in the south of the city. Many people found that these public buildings resembled cathedrals, rather than their design reflecting their function. And so at the end of the nineteenth century the capital’s two most iconic commissions, made possible by the favourable economic climate, and hence representative of Dutch national pride, were the work of a Catholic architect from Limburg.

Pure construction and craftsmanship

Pierre Cuypers (1827-1921) was born in Roermond into an art-loving family and studied architecture in Antwerp, where various teachers taught the neo-Gothic style and consequently had a lasting influence on his work. In 1849, having completed his studies, he returned to Roermond and set up his office there. At that time, the Catholic church was undergoing a revival following the restoration of the episcopal hierarchy in the Netherlands. Cuypers could not have chosen a better time to start his practice. In 1853 Roermond became once more the seat of a bishop, and one of his first commissions was to restore the chancel of its Munster church.

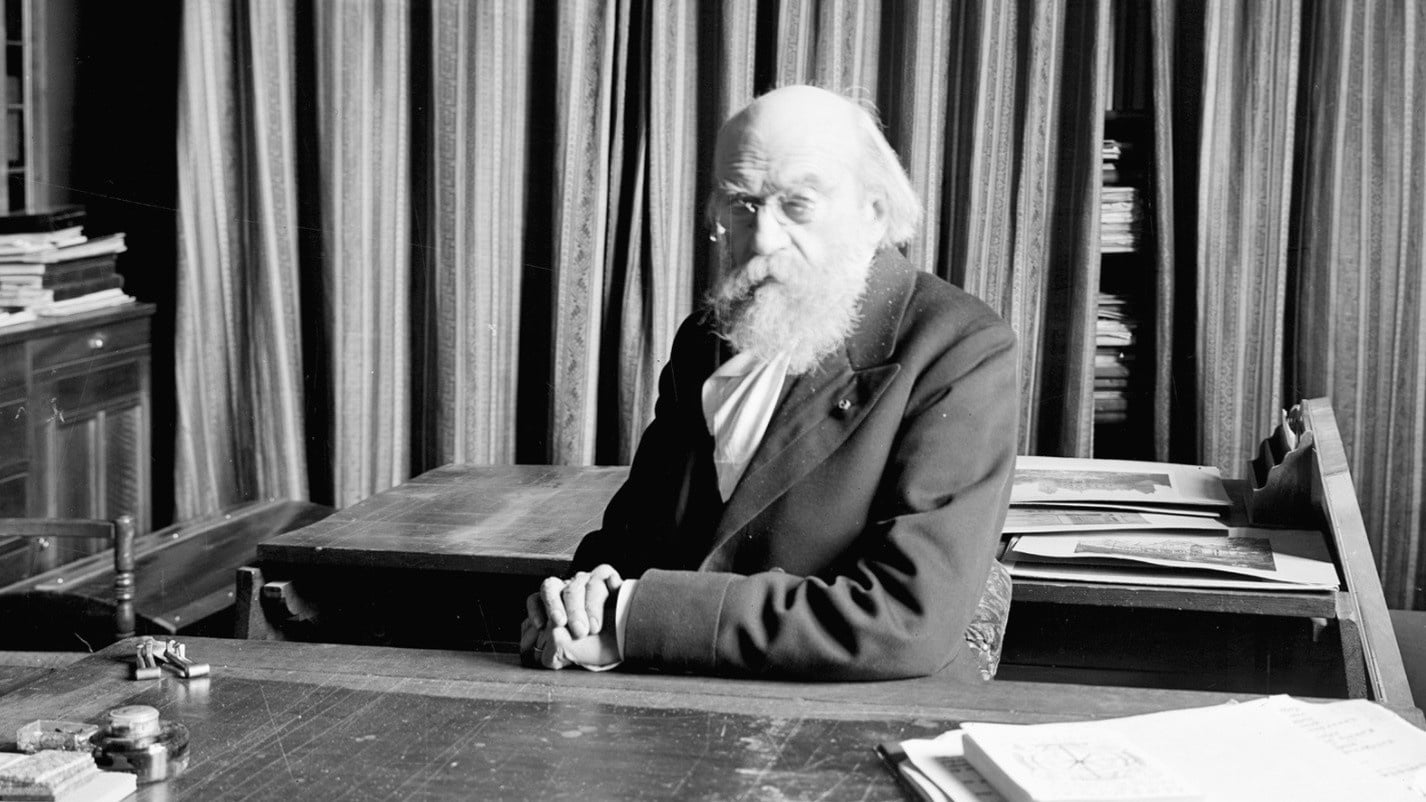

Architect Pierre Cuypers (1827-1921)

Architect Pierre Cuypers (1827-1921)© Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands

The neo-Gothic style that permeates Cuypers’ entire oeuvre was in keeping with the rhetoric of the Catholic church, but it was not only the symbolism that made it his preferred style. He was fascinated by the honest construction of the Middle Ages and by the emphasis placed on craftsmanship in that period. Cuypers believed in an ideal of community whereby architecture, combined with other forms of art, would make the world a better place, something he thought he recognised in the Middle Ages.

The design with which he won the competition for the Rijksmuseum embodied mainly Renaissance features, but the construction was to be based on the medieval model. The critics claimed that neo-Gothic features had nevertheless been incorporated into the design, and the allusions to Catholicism – which were seen as extremely inappropriate for a National Museum – gave rise to some serious polemics. However, the building has withstood the ravages of time and has later been undergoing radical renovation, based on a design by Spanish architects Cruz y Ortiz. The aim was to bring Cuypers’ original design back to life as far as possible. For example, the imaginative wall decorations and the inner courtyards have been restored. At the same time, the museum had to be adapted, so that it was better equipped to receive its countless visitors from the Netherlands and abroad.

The Rijksmuseum today

The Rijksmuseum today© kirkandmimi via Pixabay

The restoration of the museum to its former grandeur was possible because the Netherlands Architecture Institute holds the original design drawings. They are part of an extensive archive containing photographs, newspaper articles, letters, sketches, decorative schemes, technical drawings and books that belonged to Cuypers. The archive occupies some 175 metres of shelf space and comprises thousands of drawings for churches and restoration projects, houses, World’s Fairs and prestigious commissions for public works.

A castle as Gesamtkunstwerk

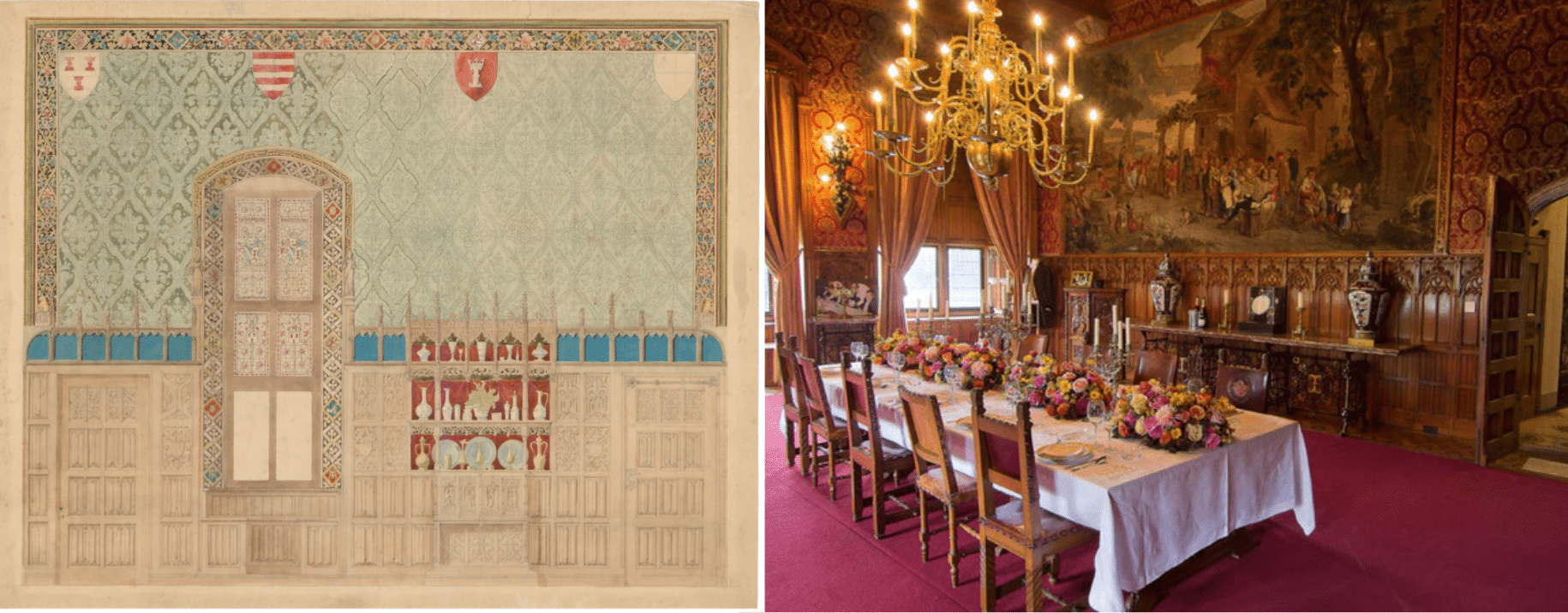

The restoration of De Haar Castle in Haarzuilens near Utrecht was also largely based on drawings in the archive. On the foundations of a fifteenth-century castle, between 1892 and 1912 Cuypers created a fairytale building that embodied all his ideas of a Gesamtkunstwerk. He designed not only the outside of the castle but also the interior, incorporating many decorative elements. Projects like these were not unusual in his work, quite a lot of which involved restoration projects. Cuypers took a fairly radical approach to his restorations. Because he usually aimed to improve on the original design, the buildings were often radically remodelled – an approach that attracted heavy criticism in the years after Cuypers’ death.

De Haar Castle near Utrecht

De Haar Castle near Utrecht© Pixabay

Cuypers went for a ‘total’ approach. He spared neither money nor effort to produce an exceptional result. Today architects outsource a great deal of their work, and only the really large firms have their own drawing department. Cuypers, though, ran his own workshop and drawing studio where, for example, the tapestries, the furniture, the bathroom taps, lift, heating systems and decoration schemes for De Haar Castle were designed.

Design of the dining room wall and dining room in De Haar Castle

Design of the dining room wall and dining room in De Haar Castle© Het Nieuwe Instituut / ANWB

The fact that Cuypers was granted the commission for De Haar Castle was due in no small part to his contacts. He was a ‘networker’ as well as an architect. In that respect, his approach was not so different from that of today’s architects. He was friendly with the most prominent members of the cultural and political elite, among them Victor de Stuers and the writer Alberdingk Thijm, his wife’s brother. He also held numerous positions such as government architect, jury member and restoration adviser, and was even involved in certain projects as a property developer.

Cuypers, the church builder

The Vondelbuurt neighbourhood is an example of this. When he acquired a site close to the Rijksmuseum, produced the urban plan and designed a series of houses (including his own), he combined the roles of architect, urban planner and developer. He also seized the opportunity of designing a church to occupy the central position in his urban plan.

Statue of Pierre Cuypers facing the Munster church he designed in his hometown Roermond

Statue of Pierre Cuypers facing the Munster church he designed in his hometown Roermond© Tripadvisor

The Vondelbuurt plans were displayed at the 2007 exhibition P.J.H. Cuypers, Architecture with a Mission, held at the Netherlands Architecture Institute in Rotterdam. The Institute, housed in Het Nieuwe Instituut since 2013, shed light on various aspects of Cuypers’ personal and professional life by focusing on the year 1877, the year in which he had just won such major commissions as the Rijksmuseum and Central Station in Amsterdam and been appointed Rijksbouwmeester (Chief Government Architect). But the exhibition showed that while he was involved in what, for the time, were megaprojects, he also continued to work on smaller commissions.

Those who took the time to study the exhibition closely were aware of the enormous diversity of Cuypers’ works. On display were sketches, presentation drawings, plans and cross-sections of the prestigious buildings, but also of the less important churches with, for example, drawings of their stained-glass windows, sculptures or mosaics. Part of the exhibition was devoted to his sources of inspiration. His personal library included books by architects such as Pugin and Viollet-le-Duc, whom he admired, as well as books containing flora and fauna that he used in his decoration schemes. It emerges that, even with such a busy work schedule, Cuypers travelled extensively in Europe, in an age when there were no planes and far fewer trains than today; and sketches from these journeys were also included in the exhibition.

In his speech at the opening of the exhibition at the Netherlands Architecture Institute the then Minister for Culture, Roland Plasterk, likened the public irritability about minarets to the reaction to Catholic church towers in the Netherlands at the end of the nineteenth century. With more than one hundred churches to his name, Cuypers made an active contribution to the emancipation of the Catholic church that claimed such a visible presence in the public space.

This text is a reworked version of the article that appeared in the yearbook The Low Countries 2008, № 16.