Robbrecht & Daem: Architectural Prowess Moved by the Muses

Recently, both the Flemish contemporary dance scene and Flanders’ theatrical productions have attracted international attention, and now it is the region’s architecture’s turn to take centre stage. One of the most distinctive representatives of this Flemish design wave is architectural firm Robbrecht & Daem. Through collaborations with a wide variety of artists they have managed to develop their own specific voice – one in which the history of architecture resounds in a most poetic way.

Bruges’ Concert Hall; museums including Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Whitechapel Gallery in London and the Lokremise in Sankt-Gallen; living and commercial spaces; a winery in Pomerol (Château Le Pin); a golf club; laboratories; archives including the municipal archives of Bordeaux; the Flemish Radio & Television Company’s broadcasting house; the City Pavilion of Ghent; a woodland cabin, and a table for Gerhard Richter; After more than three decades of collaboration, Robbrecht & Daem have managed to build a mind-boggling oeuvre.

Architects Paul Robbrecht and Hilde Daem

Architects Paul Robbrecht and Hilde Daem© Michiel Hendryckx

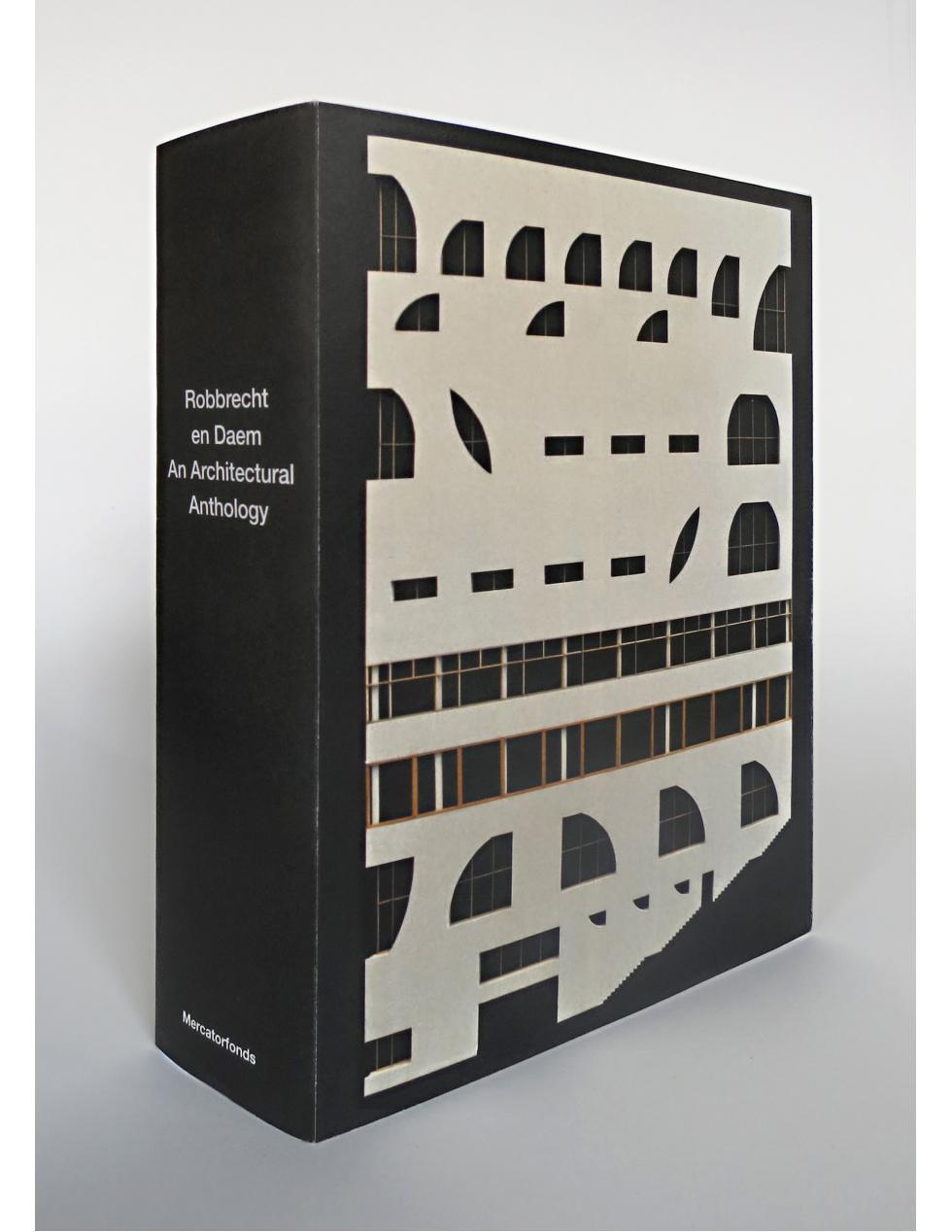

Should you need further proof, just turn to An Architectural Anthology, a detailed overview of the architects’ work, which was published recently by prestigious Flemish publishing house Mercatorfonds. The final product is a weighty tome spanning over 700 pages. Incidentally, this is a ‘mere’ fraction of their entire oeuvre, as many commissions and/or paper architecture have not been included. Robbrecht & Daem’s output definitely commands respect, not only because of its sheer size and variety, but also because of the architects’’ attention to detail during the building process, irrespective of the scale of the commissions, which range from furniture to houses, public buildings, and urban development.

Robbrecht en Daem: An Architectural Anthology

Robbrecht en Daem: An Architectural AnthologyIn this anthology there is room for a ‘puppet theatre for the grandchildren’ and for the design for a music hall in Moscow they once entered in a competition. This wide variety is characteristic of the importance the architectural firm attaches to people, but also demonstrates that Robbrecht & Daem’s vision of architecture is imbued with humanity, which is defined and shaped by play – Not in the least by the imagination of a child that still resides in the adult.

An ode to the arts

The architects’ attention to playfulness, shape, colour, rhythm, various materials, light and shadow prevents Robbrecht & Daem’s work from becoming yet another materialisation of sterile modernity, or being characterised by a generic anonymity, stripped of its past. Robbrecht & Daem take the game seriously – as one would do in the arts. In other words: The game is being played, it is given ample room, and is allowed to create a space for life itself. For this reason, their oeuvre can be regarded as an ode to architecture, as well as an ode to the arts.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam© Kristien Daem

If there is anything we can classify as ‘quintessential Robbrecht & Daem’, it must be their belief in the intimate relationship between architecture and the liberal arts. This, however, does not mean the pair intend to elevate architecture into an art form; Paul Robbrecht is too respectful of the autonomy of architecture to do so. Moreover, he distinguishes between architecture as a service, i.e. the kind of architecture that bears the responsibility to be ‘good’, on the one hand, and the arts – the so-called artes liberales – on the other, which are free to disrupt, to upset, and yes indeed: Even to be bad.

Paul Robbrecht and Hilde Daem both graduated in the mid-seventies, a time in which commissions for architects were few and far between in Belgium. This way, the pair were able to focus on school, and could really get to grips with architecture and fine arts, as well as incorporate their newfound knowledge in their initial assignments. During that period, they laid the foundations for collaborations with artists including Gerhard Richter, Isa Genzken, Juan Munoz, Cristina Iglesias, Rachel Whiteread, and many more.

Primal elements as building blocks

In 1987, Floor for a Sculpture, Wall for a Painting, was released onto the world. What was originally conceived as a temporary set-up for an exhibition at De Appel, an Amsterdam-based contemporary art institute, can now be regarded as a key moment in Robbrecht & Daem’s oeuvre. It was the basis for the widely publicised scenographies they would later put on, but mostly, it was the beginning of their numerous partnerships with figurative artists. Floor for a Sculpture, Wall for a Painting achieved exactly what is expected from architecture: to function as a transmitter or a frame for a painting and a sculpture.

Floor for a Sculpture, Wall for a Painting, De Appel, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987

Floor for a Sculpture, Wall for a Painting, De Appel, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987© Isa Genzken

By extension, you could approach this particular work as a paradigm, which illustrates how, time and time again, Robbrecht & Daem’s architecture intends to provide a medium, a location or a scene – Not just for art’s sake, but mostly for life itself. That wall and that floor ARE architecture. Both elements are primal, and lie at the very source of construction. In Floor for a Sculpture, Wall for a Painting, Robbrecht & Daem rely on some of the most basic elements in construction in order to create a meaningful context in which art can be shown, and is allowed to be art. The cinder block wall still revealed its true nature through the plaster finish. This tiny detail illustrates how important materials and being able to peal back layers are, which would go on to play an even more prominent role in Robbrecht & Daem’s work.

A wall is never just a wall

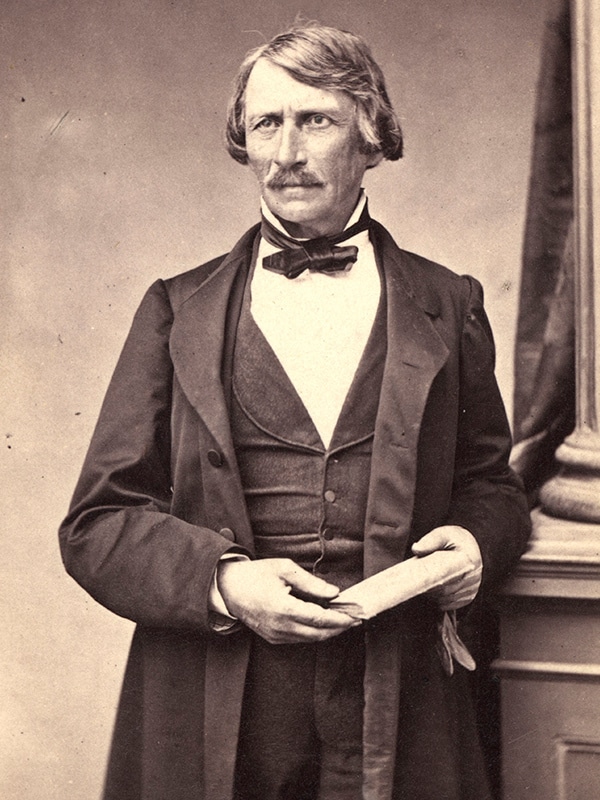

German architect Gottfried Semper (1803-1879)

German architect Gottfried Semper (1803-1879)But there is more: While exploring stone and plaster, we are able to recognise elements of traditional architectural theory, e.g. the distinction German architect and art historian Gottfried Semper (1803-1879) would make between the wall as an element of construction (as indicated by the German word Mauer) and the expression of that wall, the finishing (Gewand). The nineteenth-century architect Semper believed the latter was more important than the wall, because it shapes how we experience a space. Paul Robbrecht’s architectural focus on the Gewand is indicative of his rejection of what is known as the ‘honesty’ of modernism, which embraces exposed (stone or concrete) wall as expressions of truthful, genuine architecture, while marble and wooden cladding or wallpaper embodied dishonesty.

The richness of Robbrecht & Daem’s architectural output is directly linked to their awareness of the history of architecture. Like all great architects, they do not simply rely on theoretical insights. Instead, they draw on art history and allow themselves to be inspired by the infinite architectural ‘vocabulary’, or rather: a lexicon of images, handed down by architects from the past.

Concert Hall in Bruges

Concert Hall in BrugesMore than a generic machine

Bruges’ Concert Hall illustrates the Robbrecht & Daem method beautifully. First, we must appreciate the look of the building. Those reddish baked tiles, terra cotta or ‘baked earth’, is their reply to the brick landscape otherwise known as Bruges. Choosing brick resonates with the city’s history, the genius loci, as well as with the material the city was built with. Although its building blocks are as old as the hills, yet in the so-called ‘Lantern Tower’ it becomes part of today’s world. Vertical lines that cut the large glass windowpanes to size so they fit the medieval city add a contemporary twist to this ancient material.

The 'Lantern Tower' of the Concert Hall of Bruges

The 'Lantern Tower' of the Concert Hall of BrugesThe Lantern Tower itself brings to mind images of Italian cortile, i.e. Renaissance-period courtyards, in its own quirky way. The chamber music hall, which was inspired by a ‘set’ reminiscent of Romeo and Juliet’s age, grants the room its own individual character. Although you can almost taste the glory of the olden days, the hall’s historical inspiration simultaneously prevents the architecture to descend into a generic machine. The Lantern Tower is not just located in Bruges, but it actually co-creates the city.

Inside the Concert Hall of Bruges

Inside the Concert Hall of BrugesStrategies like these elevate Robbrecht & Daem’s architecture to an exceptional level. The large concert come conference hall, a dual purpose that often proves difficult to mange, is another successful feat of the architects. In the original design for the competition Robbrecht won the jury over by modelling the room on two hands placed around a mouth, as if you want your voice to carry further. It was to become a hall made in ‘small wooden logs’ in order to achieve a warm sound. During the drawing process, the sound engineer inspired the architects, and the design evolved into a complex back-and-forth between plaster and lines in a distinct hue. Experiencing both colour and sound, or ‘the colours of sound’, was turned into architecture, including the actual concert set.

Robbrecht & Daem allow materials to sing, construction elements to keep a beat

Architecture is to construction what prose is to poetry, or sound is to music. Similar to how Johann Sebastian Bach relies on counterpoint, colour of the timbre and texture, Robbrecht & Daem allow materials to sing, construction elements to keep a beat, or to highlight a certain part, e.g. by installing a skylight or a window overlooking the city. The pair do not limit themselves to museums or other cultural institutions.

Every single one of those resources – which all bear witness to the architects’ incredibly profound cultural background – is used in their designs, be it for a laboratory, a golf club, or as a part of the public domain, e.g. redesigning the Emile Braun Square or the Korenmarkt in Ghent.

The City Pavilion by night

The City Pavilion by night© tourism office Ghent

Sheepfold or City Pavilion?

The aforementioned Ghent design became known internationally because Robbrecht & Daem – in collaboration with fellow architect Marie-José Van Hee – took the unsolicited initiative to conceive a brand-new City Pavilion. This construction has now become part of the Ghent social scene, despite its questionable badge of honour, i.e. ‘the sheepfold’.

Crucially, the architects were not just handed this commission, on the contrary. While the competition for the design of an underground parking lot and the Emile Braun Square was still ongoing, they decided to radically oppose the idea of an underground garage, thus risking disqualification. The architects proposed putting a halt to parking vehicles in the city centre. Instead, they designed a City Pavilion, inspired by the town’s historic (mediaeval) morphology, which had provided Ghent with some much-needed structure after the nineteenth-century demolition.

This was followed by a lot of commotion, a second round in the competition, and even a referendum. Eventually, the Ghent city council agreed with the architects’ resistance to an underground parking lot. Robbrecht & Daem finally got the go-ahead to build the unsolicited – or ‘unnecessary’, according to a few gossips, City Pavilion.

Inside the City Pavilion

Inside the City Pavilion© Bert Callens

Social responsibility

It does not just take courage, but also a significant amount of social responsibility and vision to relegate a competition initiated by a commissioning town council to the bin, and to then offer an alternative, which is fully committed to the public domain’s cultural heritage. That might have been one of the single most memorable and honourable achievements in Robbrecht & Daem’s careers. After all, hundreds of architects would have jumped at the chance to build whatever was commissioned. Instead, these architects never stopped defending ‘l’architettura della Città’ in a critical, constructive and imaginary way, always mindful of what is for the good of all.

Robbrecht & Daem – An Architectural Anthology, edited by Maarten Van Den Driessche, Mercatorfonds, Brussels, 732 pages. More information: www.robbrechtendaem.com.