Roger Raveel in BOZAR, Artist Against the Current

Roger Raveel (1921-2013) would have celebrated his 100th birthday in 2021. In his centenary year, the Centre for Fine Arts of Brussels is paying homage to this extraordinary and multidisciplinary Flemish artist with a retrospective curated by German art historian Franz Wilhelm Kaiser. An exhibition that directs long overdue attention to one of the great Belgian artists of the post-war period, who developed an unprecedented visual language mid-way between figuration and abstraction.

While Roger Raveel enjoys a high reputation in the artistic milieu of the Low Countries – he even has his own museum devoted to him in Flanders -, it must be acknowledged that, regrettably, he remains virtually unknown to the rest of the world. Let us begin by trying to understand the reasons for this.

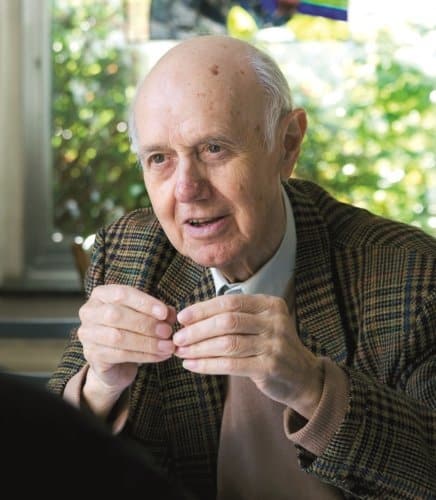

Roger Raveel

Roger Raveel© Roger Raveel Museum

Recall that Raveel’s career began at the start of the 1950s, a period where the art world had its eyes firmly set on the international level, and notably the two major centres of the avant-garde movement: Paris and New York. Our young painter, although well aware of what was going on elsewhere (he notably references Fernand Léger and Mondrian), passionate about art history (with a particular admiration for Giotto and Van Gogh), had no desire to leave his little village in East Flanders, where he spent almost his entire life. He actually preferred the ‘local’ to the ‘global’.

Roger Raveel, Woman with Make-up Mirror, 1953, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum

Roger Raveel, Woman with Make-up Mirror, 1953, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum© Raveel – MDM. Foto: Peter Claeys

Raveel’s invisibility abroad can also be explained by the predominance of the abstract current, artists having turned their backs on the figurative movement and thus all identifiable representation. Raveel absolutely did not adhere to this mode of expression. Quite the contrary! He lived solely for the direct observation of his environment, in a fully recognisable manner. The bitter conclusion remains that, by refusing to submit to the artistic dictates of the time, Raveel missed the train of ‘modernity’ and, for this reason, did not enjoy the success he deserved.

Bozar remedies this injustice by putting the spotlight back on this major, radical and non-conformist artist, who represented Belgium at the Biennial of Venice and at Documenta 4 in Kassel in 1968.

Roger Raveel, Man with Wire in Garden, 1952–53, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum

Roger Raveel, Man with Wire in Garden, 1952–53, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum© Raveel – MDM. Photo: Peter Claeys

Bringing together over 150 works, Franz Wilhelm Kaiser has opted for a thematic presentation. The reason? ‘There is virtually no linear evolution in the work of Roger Raveel, but rather a succession of highly idiosyncratic inventions at pivotal moments in his career.’ It is true that in the corpus of the Belgian artist one finds a multitude of specific motifs that recur throughout his career (gardens, carts, tables, squares, etc.) as well as new forays incorporating objects (mirrors, wheels, birdcages, etc.). And indeed, that is why the exhibition’s curator maintains that ‘Raveel’s work is instantly recognisable’.

We thus discover an exhibition articulated around ‘ten chapters’, entitled respectively ‘Self-portrait’, ‘Without Identity’, ‘Interior & Exterior’, ‘Striped’, ‘Modernity in the Countryside’, ‘Closer to Nature’, ‘The Square’, ‘Combines’, ‘The Cart’’ and finally, ‘Monumental Statements’.

The importance of recurrent motifs

During his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts of Ghent (1942-1945), Raveel became acquainted with the painter Hubert Malfait. A decisive encounter, since the latter advised him to abandon the academic style and observe what was around him. This proved to be a revelation. Roger Raveel destroyed his works inspired by Flemish expressionism and as of 1948 began to adopt an atypical form of realism, precisely at a moment when the art world swore by abstraction alone.

Roger Raveel, Little Table with Red Blot, 1952, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum

Roger Raveel, Little Table with Red Blot, 1952, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum© Raveel – MDM. Photo: Peter Claeys

He drew his favoured themes from his immediate environment: his interior, his garden, the cart, the modernisation of the countryside, his wife and his father. Stylistically, he oriented himself on a realism mixed with abstract forms characterised by emphatic contours and intense, vivid colours, contrasted with black or white.

In the first self-portraits, dating from around 1946, the tonalities evoke the greens and browns of nature. In 1948, he married Zulma, a neighbour nine years older than himself, who would support him throughout his career. His portrait of her shows a restrained woman wearing glasses, unsmiling, with a bob cut, against a grey background. Here nothing is romanticised or sublimated, the artist represents his wife realistically, just as she is.

Roger Raveel, Woman with Red Arm, 1949–51, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum

Roger Raveel, Woman with Red Arm, 1949–51, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum© Raveel – MDM. Photo: Peter Claeys

Because it is precisely the banality of day-to-day existence that prompts Raveel to go ever further in his experimentations and stylistic combinations. The kitchen and the garden are two major sources of inspiration. In the first, a table, which the perspective makes less profound, more oblique or frontal, on which are posed objects that are sometimes recognisable (a coffee pot, a revolver, a plant, a pair of scissors), sometimes not (such as this abstract red spot, which recurs mysteriously).

Behind the house, the theme of the garden, where he often depicts his father as a ‘man bending forward’. The 1948 canvasses foretell the evolution of his stylistic quest. The forms simplify and the austere tones are replaced by more vivid, fauvist variations. As one can see in this extraordinary oil painting Woman with Red Arm (1949-51), constructed in flat areas of the colours red-green-yellow, highlighted by thick black lines.

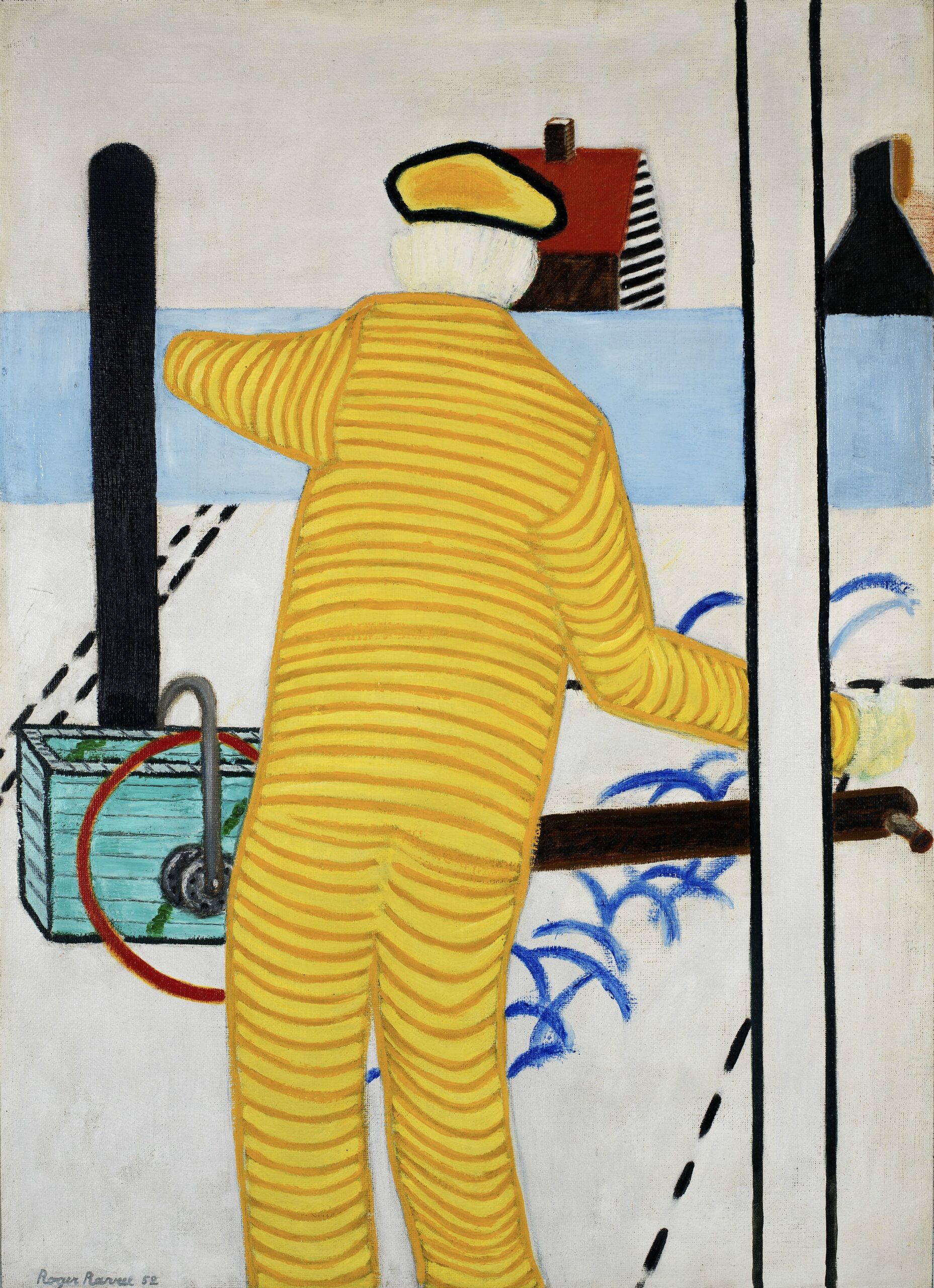

Roger Raveel, Yellow Man with Cart, 1952, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum

Roger Raveel, Yellow Man with Cart, 1952, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum© Raveel – MDM. Photo: Peter Claeys

The traits of the face quickly disappear (Self-Portrait with Cigarettes, 1952) or find themselves covered with multi-coloured squares (Homme avec fil de fer au jardin, 1952). The everyday man becomes universal. His garden cart also becomes one of the recurrent motifs in his work and finds itself in the painting in the form of an installation.

Roger Raveel, Football Field, 1952, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum

Roger Raveel, Football Field, 1952, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum© Raveel – MDM. Photo: Peter Claeys

Raveel progressively becomes the observer of the changes taking place in his village. He calls this phenomenon ‘the slow infiltration of modernity’. His canvasses become covered with concrete posts and walls. (Football pitch, 1952). There is also the presence of these figures striped with parallel lines that entirely model the characters (Yellow man with cart, 1952). “A typically Raveelian characteristic” notes the curator. Or this ‘square’ affixed to the canvas, sometimes all red, sometimes all white. Impossible not to see the reference to Malevich here.

New vision

From the 1960s to 1990, the artist moves toward paintings with which he associates recovered materials and also begins to create installations in situ, wall frescoes of impressive dimensions, and even performances.

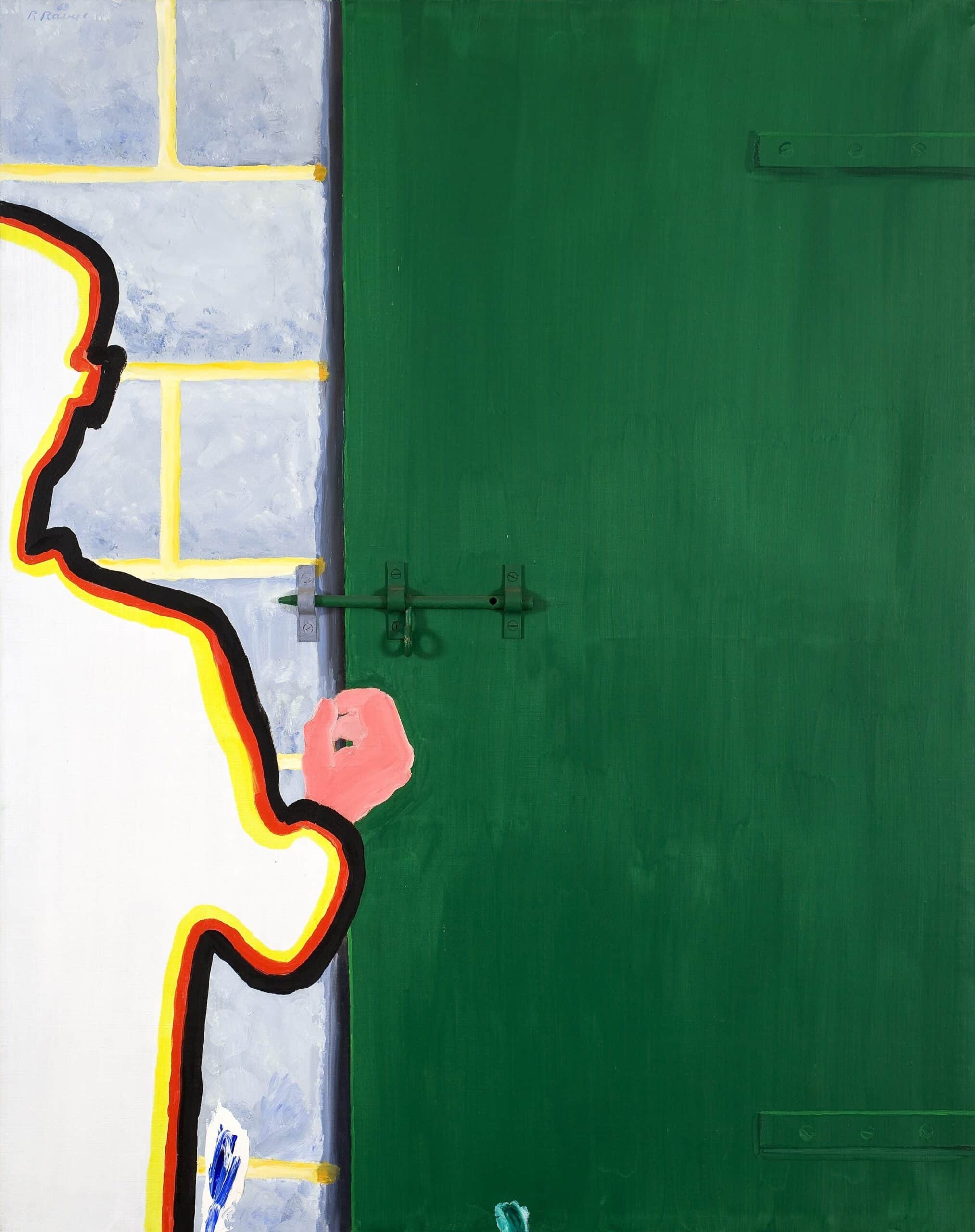

Roger Raveel, Man in front of a Bolted Door, 1969, Private collection

Roger Raveel, Man in front of a Bolted Door, 1969, Private collection© Raveel – MDM

Deeply impressed by the Combines of Robert Rauschenberg, which he discovered during a trip to Italy, Raveel explores in his own manner the incorporation of objects into his paintings. He integrates a curtain (The Little Curtain, 1963), a coat rack, a mirror (Mirror Woman, 1965), going as far as to transform the frame into a window (The Window,1962). A way to abolish the limits of the canvas so that it “bursts forth into space”, he said.

He is also fascinated by winged creatures, which he tries to incorporate into his paintings. In 1962 he introduced a live turtledove in a cage, during his first monumental statement Farmyard with live dove. He continues his original experiment, with canaries this time (A terrible, beautiful life a.k.a A dreadfully pleasant life, 1963).

Roger Raveel, The Window, 1962, Private collection/Roger Raveel Museum

Roger Raveel, The Window, 1962, Private collection/Roger Raveel Museum© Raveel – MDM. Photo: Peter Claeys

In the 1970s, he launched himself into large-scale frescoes of coloured characters marching in demonstrations (The Parade of Paintings from 1978 in Machelen-aan-de-Leie, 1978). One finds here the artist´s favourite themes, such as the square, the striped fellow or the man whose face is covered with squares, but also his aesthetic aspects such as the white background, the flat coloured areas and his trio of red-blue-yellow, as well as the frontality excluding any perspective, rendering the canvas two-dimensional.

Roger Raveel, The Meaning of Nonsense, 1990, Archives Luc Levrau

Roger Raveel, The Meaning of Nonsense, 1990, Archives Luc Levrau© Rony Heirman, Tim Heirman

This way of creating is so novel that his Flemish friend and poet Roland Jooris even invented a name for it: “New vision”! On 10 May 1990, fifty years after the total destruction of his childhood home by bombs during World War II, Raveel wanders through the streets of Brussels, pushing in front of him a wardrobe on casters (like an avatar of the cart in his garden), equipped with a mirror in which one sees the reflection of the passers-by. The event called Le sens de non-sens might seem absurd in the ‘surrealist’ manner, but the purpose, he said, was to “denounce the horrors of World War II”. The artist remained rather silent about this trauma throughout his life.

Roger Raveel, Cart to Carry the Sky, 1968, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum

Roger Raveel, Cart to Carry the Sky, 1968, Collection of the Flemish Community/Roger Raveel Museum© Raveel – MDM. Photo: Peter Claeys

This exhibition demonstrates Roger Raveel’s immense talent, importance and contemporaneity. The works one discovers here are exciting, powerful and amusing. One really feels to what an extent the Belgian master never ceased to press forward in his explorations, while maintaining his determination against all opposition, creating a surprising artistic lexicon to which he remained loyal to the end.

The only regret about this very beautiful retrospective is the decision to present the works in thematic chapters, which tires the eye by obliging it to view five paintings of kitchen tables, carts or striped characters gathered in a single hall. Even if the idea is interesting, it remains too pedagogical for an artist of such great complexity. It would have been preferable to see the works confront one another and enter into dialogue. But this should by no means stop you from visiting the exhibition, which is unquestionably this spring´s major artistic event.

Roger Raveel. A Retrospective, until 21 July, BOZAR, Brussels

Roger Raveel Museum, Machelen-Zulte