Sarah Timmer Harvey’s Choice: Astrid Roemer and Maurits de Bruijn

Each month, a Dutch-to-English translator shares literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. This time, the choice is up to Australian-American writer and translator Sarah Timmer Harvey, whose translation of Jente Posthuma’s novel What I’d Rather Not Think About was shortlisted for the 2024 International Booker Prize. Sarah selects two literary gems: a haunting portrayal of Suriname and a sharp critique of masculinity and power in the art world through a queer lens.

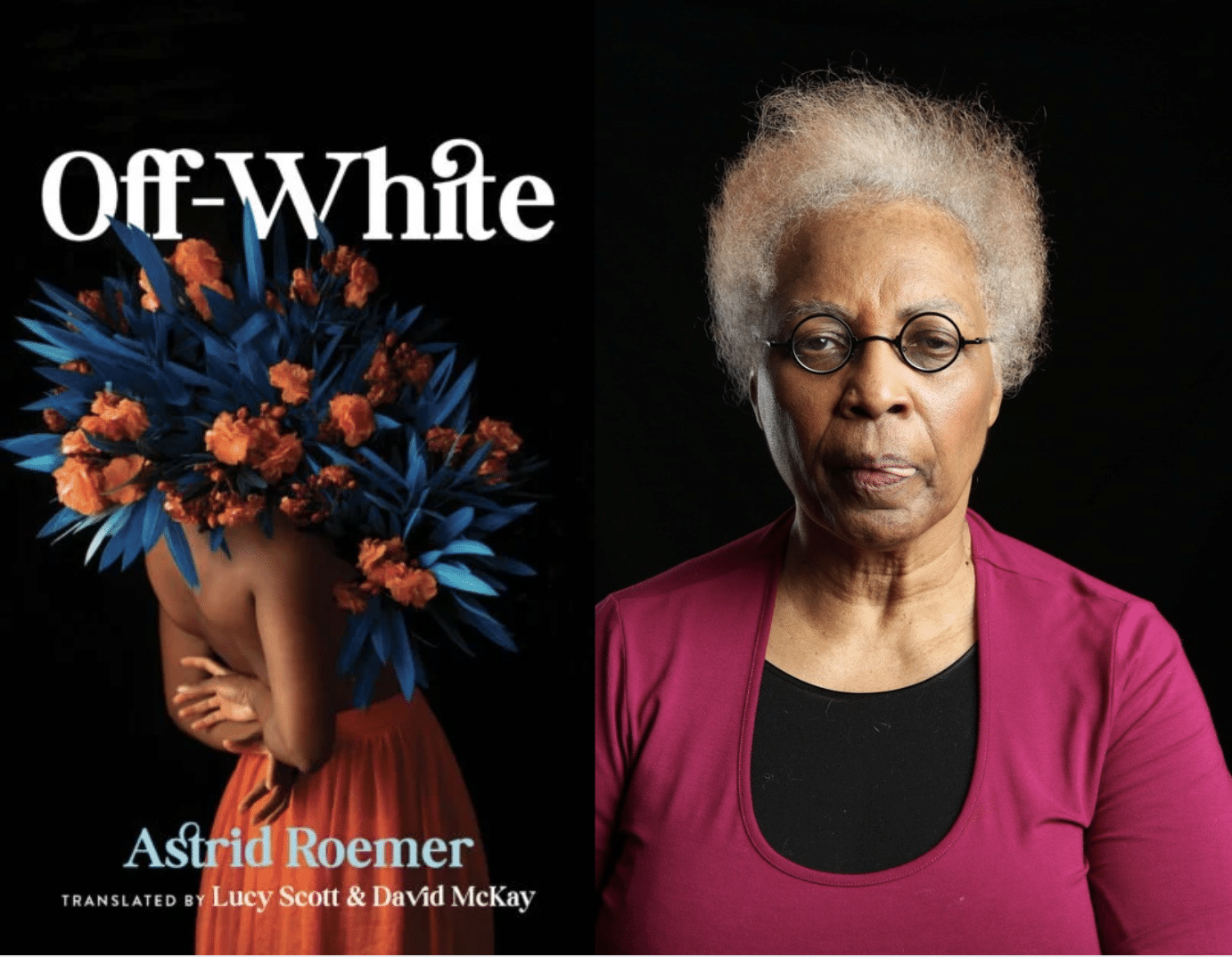

Must-read: ‘Off-White’ by Astrid Roemer

Astrid Roemer

Astrid RoemerAstrid Roemer’s Suriname pulses with poetry, community, sensuality, language, and the specter of Dutch colonialism. Born in Paramaribo in 1947, Roemer published her first collection of poetry in 1970, followed by her debut novel in 1974. Aside from Suriname, Roemer has lived in both the Netherlands and Scotland but intriguingly also spent fifteen years travelling the world with just “a cat, backpack and laptop” while continuing to publish novels, poetry and plays. In recognition of her extraordinary contribution to Dutch literature, Roemer was awarded the prestigious P.C. Hooft Prize for her oeuvre in 2016, and the Dutch Literature Prize in 2021.

More recently, Roemer’s highly acclaimed novel, On a Woman’s Madness, was translated into English by Lucy Scott for Two Lines Press. Scott’s translation, which was longlisted for the American National Book Award in 2023, introduced English-language readers to Roemer’s lush and immersive exploration of queerness, misogyny, and anti-blackness in Paramaribo in the 1960s. For Roemer’s latest novel, Off-White, Scott collaborated with award-winning translator David McKay to produce a thoughtful and vivid co-translation published in 2024.

Off-White returns to Suriname in 1966, as the former colony is on the brink of gaining independence from the Netherlands. Roemer’s narrative focusses on the multiracial Vanta family whose resilient matriarch, Grandma Bee, is gravely ill and contemplating her legacy in light of her family’s complex history. As Bee’s condition deteriorates, shocking secrets and new perspectives are slowly revealed by other family members, including Heli, Bee’s favorite granddaughter, who was exiled to the Netherlands after an affair with her married teacher.

The novel charts five decades of upheaval and growth in a family whose identities are inextricably bound to a history thrust upon them by the Dutch Empire. Roemer never shies away from revealing the scars that slavery, religion and colonization have left on the Vanta family. But her writing also relishes the many ways her characters care for one another, their quiet victories, covert passions, shared meals, and the exuberant colors of their homeland. Off-White is a layered and haunting portrayal of Suriname from a writer whose voice is unequalled in the Dutch literary landscape.

Astrid Roemer, Off-White, translated from the Dutch by Lucy Scott and David McKay, Two Lines Press, 2024, 377 pages

To be translated: ‘Man maakt stuk’ by Maurits de Bruijn

Maurits de Bruijn

Maurits de BruijnRazor-sharp, unpredictable and gloriously queer, Man maakt stuk (Man Made) is Maurits de Bruijn’s third novel and without doubt, one of the most exciting Dutch-language books released in the past year. Set in gentrified Amsterdam, Man maakt stuk finds promising visual artist David in a rut and struggling to match the career success of his friends from art college. To make matters worse, a group of young men have taken to hanging out in front of David’s apartment at all hours of the day and night. Loud and disruptive, the group has David’s well-heeled neighbors up in arms, but David, himself an outsider, refuses to take action. Instead, he begins to observe the group, developing an obsession that bleeds into his work and relationships with disastrous consequences.

Man maakt stuk is a searing dissection of masculinity, heteronormativity, and power in the art world through an unapologetically queer lens. In a long-form confession addressed to his art dealer, David reveals the true nature of his interactions with the group, confessing everything that has informed and fueled his surprising new work. De Bruijn’s narrator is endearing and principled but spectacularly flawed in his own way, adding tension and intrigue to this remarkably witty and well-observed take down of the status quo.

Maurits de Bruijn, Man maakt stuk, Das Mag, 2024, 269 pages

Excerpt from ‘Man maakt stuk’ (Man Made), translated by Sarah Timmer Harvey

That spring, I ran into an old friend in the supermarket. It wasn’t someone I hated, just someone who had slipped away from me. Luke asked how things were going and because I didn’t have much to say, I told him about the group of guys who hung out underneath my window. ‘So, kind of like a gang, who are out to make your life miserable,’ joked Luke and I laughed and started to miss him because he was the master at making trivial jokes. Once, during a night out, we tried to seduce the same guy, and the object of our desire had observed that both Luke and I always spoke in hyperbole. Everything was either awful or fantastic, terrible or amazing and we paid no attention to the gray area between the two extremes. When it came to us, there was a complete and utter lack of nuance. I knew immediately he was right. Luke and I tried to outdo each other so often that “just fine” had ceased to exist.

I told Luke I’d recently been thinking about my ex-lovers and hook-ups, all of my sex partners. At least, not necessarily about them, but the space we’d been allocated by the outside world, all the places we took cover. Places I couldn’t exactly say were ours. And I said to him, right in the middle of the aisle at the supermarket, that my exes and I had always shut ourselves away and the intimacy we shared was hidden. Luke nodded. All of it happened in bedrooms, or at the very least, in living rooms or kitchens, when one of us lived alone as I did now. Luke nodded again. Even my ex—whose housemate was truly never at home, because he worked all the time and was always at his girlfriend’s place when he wasn’t working—even that ex had never once kissed me in the kitchen, bathroom or in passing in the hallway. It’s not as if I desperately wanted to fuck on the street, I said, but it’s something I’ve been noticing ever since that group of guys started hanging out in front of my place. They’ve made themselves completely at home in a space that, in principle, should belong to everyone and maybe I do feel threatened by that. Luke stopped nodding, and I saw in his streamlined face that he was about to correct me.

‘But you could also look at it the other way around,’ he said. ‘You and the guys you were sleeping with, you had access to the houses, bedrooms and kitchens. And because of this you had the privilege of being able to retreat to those spaces, to conceal yourselves. And this group of guys don’t have that. They’ve been relegated to a tiny section of the street in front of your house.’

‘But what if it had been a group of young women? No,’ I said, answering my own question, ‘It’s impossible to imagine that happening. You know what I mean? They would never claim the street as their own.’

‘True,’ he said. ‘Just like it’s impossible to imagine a bunch of queens doing it. But I don’t need to explain to you that privilege isn’t absolute.’

END

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.