Roelant Savery Painted the Emperor’s Wondrous World

Mauritshuis in The Hague is paying tribute to Roelant Savery with 43 paintings and drawings. As a court painter in the service of Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg, the seventeenth-century master feasted his eyes on lions, flowers from every corner of the world and the legendary dodo as well, capturing all of them in his inimitable style.

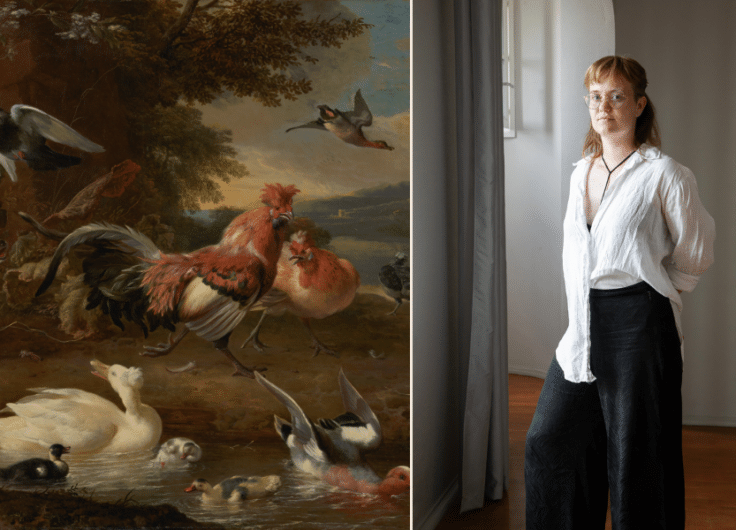

Wandering around in the painting is a sensational experience. The lion couple and the horses, the fallow deer and the roes, a camel and a rhinoceros, a cockatoo, chickens and a rooster, and, yes indeed, the dodo. Birds of all kinds caper among the tulips or fly among the foliage and the rocks, some with strangely stiff legs. Somewhere – you have to look for him – Orpheus plays his harp. He enchants all the animals, which is why they all live together so peacefully in this zoological garden full of animals from all continents. To the right of the centre, an ostrich rises. Behind it stretches a vast landscape that eventually dissolves into a delicate blue.

It is a spectacle that Roelant Savery (1578-1639) could never have actually seen, there is no world where lions recline on tulips or where a hippopotamus climbs a mountain, and the dodo was already extinct. No wonder the Stadholder Frederik Hendrik and Amalia of Solms wanted to have this painting in their collection. Behind the hills in the distance, I imagine Prague, where we could find Emperor Rudolf II in his palaces, in the midst of his art collections and his menagerie full of exotic animals, the emperor of a court that was one of the main centres of art and science in Europe.

Orpheus Charming the Animals with His Music, 1627

Orpheus Charming the Animals with His Music, 1627© Mauritshuis, The Hague

Orpheus Charming the Animals with His Music is one of three paintings by Savery in the Mauritshuis collection. It arrived there via the collections of the eighteenth-century stadholders. In 2016, Peasants Dancing outside a Bohemian Inn, a donation from Willem Baron van Dedem, followed. The same year Mauritshuis managed to acquire the magnificent still life, Vase of Flowers in a Stone Niche, at the TEFAF fine arts fair for €6.5 million. Now the three works hang, as part of Roelant Savery’s oeuvre, in a fairytale exhibition that has brought together 43 of the master’s paintings and drawings. An informative and enjoyably written catalogue accompanies the exhibition.

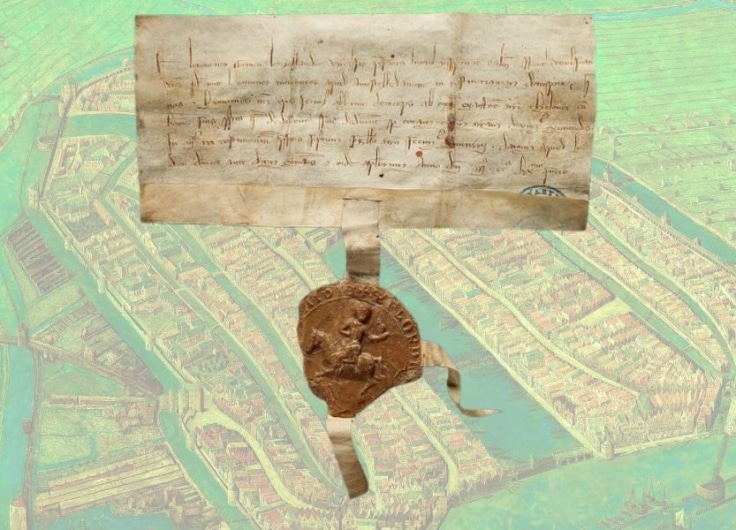

Prague

Let us start at the beginning, with Roelant Savery’s Anabaptist parents who, with their five children, fled Kortrijk and the Catholic troops sympathetic to the Spanish. Around 1584, they emigrated via Bruges to Harlem, where they built up a new life. They were not the only newcomers and, thanks to the many immigrants from the Southern Netherlands, the arts flourished in the Northern Netherlands. Of the five Savery children, three became artists. Roelant, the youngest, became the most famous.

He was apprenticed to his brother as a twelve-year-old, but little is known of Roelant’s early works. His career took off when he was given the opportunity to enter the service of Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg (1552-1612), “the greatest lover of paintings in the world, these days”, according to his contemporary, the art historian Karel van Mander. So Savery left for Prague in the autumn of 1603 or the spring of 1604 – a twenty-something embarking impetuously on a new life. Unfortunately, nothing came of the plan to travel to Prague with his brother Jacob, who died prematurely of the plague.

View of Prague, 1604-1608

View of Prague, 1604-1608© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Roelant Savery must have feasted his eyes there. Under the patronage of Rudolf II, the court had developed into one of the most important centres of art and science in Europe. The emperor built up a phenomenal art collection for which he brought the best painters, sculptors, stonecutters and silversmiths to Prague. He also took a keen interest in both the exact and the occult sciences, employing scholars who had made a name for themselves in the fields of botany, medicine, antiquities, mineralogy and alchemy.

In the imperial art gallery, designed by Hans Vredeman de Vries and his son Paul, Savery saw artworks from all over Europe. In the Kunstkammer he admired minerals, rare shells and stuffed animals, like the dodo. Lions and apes populated the imperial zoos, exotic birds screeched in aviaries. And somewhere in a study, the imperial mathematician rediscovered the world. Savery embraced it all and painted the emperor’s wondrous world with a confidently precise brush on panel and copper.

A dodo with some other birds, c. 1630

A dodo with some other birds, c. 1630© Natural History Museum, London

Landscapes, too, had to be part of the royal encyclopaedic collections, so Rudolf II sent Savery to the Tyrol “to sketch all the fine faces of the landscapes and waterfalls from life”, as biographer Arnold Houbraken put it. And so it happened. Savery portrayed waterfalls, rock formations and sometimes monstrous-looking groups of trees for the emperor. Back from his expeditions, he took his sketchbook out and about in Prague, where he recorded daily life with his pen, chalk and black lead. The drawings are sometimes moving, because they bring us so close to the people Savery also saw. On the drawings on which he put comments, we read – along with Savery – “black and white floral”, next to the clothing of the Jews Praying in the Synagogue, “red silk” and “white silk”.

Sleeping young man, probably poet Pieter Boddaert (1576-1625), 1606-1607

Sleeping young man, probably poet Pieter Boddaert (1576-1625), 1606-1607© P. & N. de Boer Foundation, Amsterdam

Some of Savery’s drawings feature the earliest known depictions of contemporary European Jews. The details of the carvings on the bench on which the Jews are sunk in prayer are so accurately rendered that we know for sure that the drawing was made in the Neualtschul in Prague, which still exists. On the back of the same drawing, Savery made a sketch as well, a young man with tousled hair dozing in a chair, with his hand in his doublet. It is probably poet Pieter Boddaert.

Sensual indulgence

Rudolf II died in 1612, bringing an end to imperial patronage. Around 1616, Savery could be found in Amsterdam again. There he painted the remarkable work Cows in a Stable; Witches in the Four Corners, with witches flying in the four corners of the painting. Funny, but not that funny really: this was the period when witch hunts were at their height.

In 1621, Savery bought a house in the Boterstraat in Utrecht, which he named Het Keyserswapen (The Imperial Arms) in memory of his patron, and he continued to use the drawings he had made in Prague as models for the flowers and animals that still populated his paintings. But his years in Prague increasingly faded away, like a beautiful dream from the past.

Savery was one of the pioneers of the still-life genre, which was a new subject in painting in the Low Countries around 1600

Although he continued for a while to be part of a group of prominent Utrecht artists, the quality of his work declined little by little “Nature stole his life with sensual indulgences” reads a text under his portrait print. He ran up debts, too, perhaps because when he drank he could easily be persuaded to sign something or other and he was swindled by various people as a result. In February 1639, at the age of 61, he died, destitute and bankrupt.

Magic wand

The light in the exhibition hall is subdued – paintings and drawings hang side by side, and drawings simply cannot tolerate much light, so if you go to see the exhibition, take your reading glasses with you. Slowly I emerge from the paradisiacal landscape with Orpheus.

Vase with flowers in a stone niche, 1615

Vase with flowers in a stone niche, 1615© Mauritshuis, The Hague

A few paintings further hangs the sublime still life that Mauritshuis bought in 2016. Savery was one of the pioneers of the genre, which was a new subject in painting in the Low Countries around 1600. In the imperial gardens in Prague, he had been able to study hundreds of plant and flower species. Here, just as he did in his paintings of the animal kingdom, he did the impossible, bringing flowers from all corners of the world into bloom at the same time with his magic wand.

As I look at the still life, I realise how many sounds Savery has hidden in his paintings and drawings: the rushing of waterfalls, the fluttering of witches on their broomsticks, bird song, an elephant rubbing its thick skin against a tree, Prague Jews praying in the synagogue. And even in this still life, a peerless trompe l’oeil, I can hear the bluebottle buzzing, a lizard rustling in the leaves. Some of these sounds echo through the exhibition hall, too. But what did the dodo’s call sound like? What did the world that is now disappearing under our eyes sound like?

Two horses and their handlers, 1628

Two horses and their handlers, 1628Collection Abby Kortrijk

Back outside the exhibition, I watch the introductory film which, with beautifully chosen animations of a few paintings, gives further context to Savery’s oeuvre and captures some of the details better than in the dark exhibition hall. The flowers of the corona imperialis or crown imperial sway in the breeze.

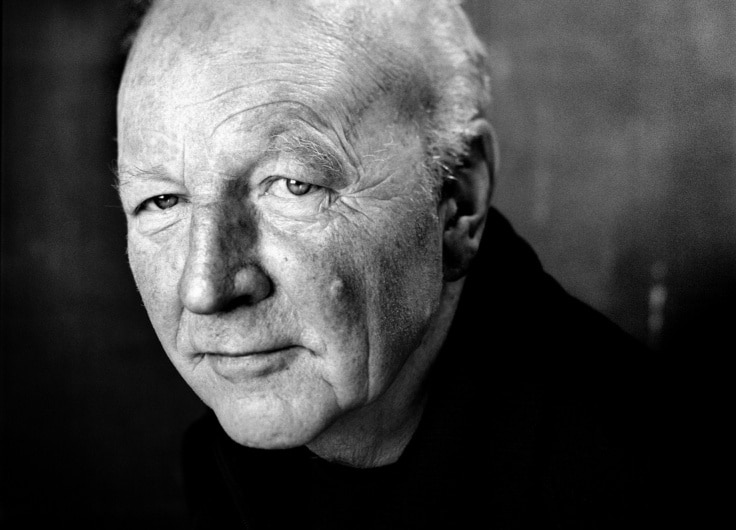

Roelant Savery’s Wondrous World can be seen at Mauritshuis until 20 May. A catalogue of the same name, by curator Ariane van Suchtelen, has been published by Waanders to accompany the exhibition.