Sibling Rivalry. Playing Football for the Honour of the Low Countries

The eyes of Belgian football fans shine when they talk about a match in which the Red Devils defeated the Netherlands. The matches between the two national teams have more than once been played on a razor’s edge – or at least for the Belgians, the Dutch shrug their shoulders. This one-sided rivalry has a sporting, but also historical background.

My love of football began at a match between Belgium and the Netherlands. I was eleven. Both countries had landed in the same group at the 1994 World Cup and weeks before the tournament started, the press and the rest of football-loving Flanders were eagerly looking forward to nothing more than that specific confrontation. Barely able to contain all the built-up excitement, I sat on the floor of our living room that Saturday evening in June for what was to be a heroic spectacle. Under the scorching sun in Orlando, Florida, the teams played a frenzied game, with both goalkeepers coming under constant fire. After just over an hour, Philippe Albert worked the ball into the goal after an extended corner kick: 1-0 to the Belgians. Though the rest of the tournament would consist of disappointments for Belgium, that one victory was more than enough for us. THE prize had been won: we had beaten the Netherlands!

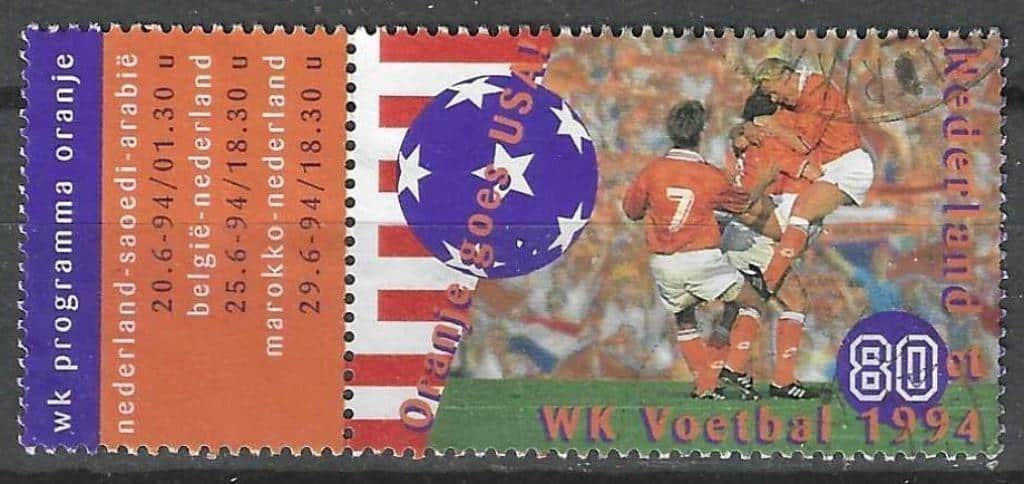

Dutch stamp on the occasion of the 1994 World Cup in the United States

Dutch stamp on the occasion of the 1994 World Cup in the United States© ebay

An intense brotherhood

The eighties and nineties were marked by hotly contested rivalries between Belgium and the Netherlands. The two countries did not meet very often on the pitch, but when they did, it was guaranteed to be a match worthy of intense dedication. There was the header goal by Georges Grün in Rotterdam, which ensured that Belgium – and not the Netherlands – qualified for the 1986 World Cup. There was the 0-0 draw at the 1998 World Cup in France, in which the Belgian Lorenzo Staelens badgered his direct opponent Patrick Kluivert so personally that Kluivert elbowed him. Then there was the flashy 5-5 tie in 1999, a duel between two teams, neither of which would give even an inch, despite the fact that it was meant to be a ‘friendly’ game. Both teams ran around like kids in the schoolyard for 90 minutes, in a match that combined a little bit of playing around with some tactical discipline.

These encounters were fought almost as intensively in the Flemish newspapers as on the pitch. Any Low Countries competition in that period was invariably accompanied by weeks of previews, interviews and analyses. Each defeat was hard, and any victory was remembered and re-lived for months. At a time when the Red Devils seldom achieved high scores at international tournaments, winning against their northern neighbours was a goal still within reach. Even today, some fanatics consider simply ‘doing better than the Netherlands’ as a competition in itself. After Belgium qualified for the 2018 World Cup in Russia, something the Netherlands had failed to do, a banner appeared above a highway bridge close to the border that read: The World Cup begins here!

Little brother, big brother role reversal

For the majority of Belgians, however, something seems to have changed in the past few years. On 3 June 2022, Belgium and the Netherlands met on the group stage of the Nations League. Not exactly the most important tournament in the eyes of players and audiences, but still a game worthy of commitment and, moreover, the first time the two teams had faced each other in more than three years. Yet the Belgian media paid little attention to the impending confrontation. No previews with an extensive historical overview, no interviews with ex-players from both countries, no ‘ten reasons why fans should absolutely not miss this match’. Ten or twenty years earlier, each and every such contribution would have been indispensable.

(left) fans of the Belgian Red Devils (right) fans of the Dutch team

(left) fans of the Belgian Red Devils (right) fans of the Dutch teamIt is clear that the rivalry mainly originates in Belgium and generally begins with the Flemish accusing their Dutch neighbours of misplaced arrogance, making jokes about how stupid or stingy the Dutch are and mocking both their austere food culture and their mispronunciation of French. In the Netherlands, on the other hand, Belgium is not generally a topic at the forefront of discussions. Yes, every now and then someone will make a Belgian joke, but as an aside, a throw-away remark offered without much conviction. Such a joke will never be told with the same explosive mixture of fun and venom with which a Fleming laughs at a Dutchman, and preferably when one is in the company to witness it. (As part of a mixed family I can say with some authority that nowhere can this dynamic be seen more clearly than during a family celebration, when one party loses itself completely in a feud of its own making, firing joke after joke, while the other party shrugs and shows little interest.)

The same one-sided dynamic also exists in football. Certainly, the defeat in 1985 hurt the Netherlands, but apart from that match, the Red Devils have hardly put anything in the way of Orange when it comes to football. In fact, the Dutch tend to see Germany as their historic rival, an opponent with whom they have effectively competed for a world title as well as a country that has left wounds outside of the sporting realm, wounds that did not fully heal for a long time. Belgium is just a side note for the Dutch. Just as the country is seen as merely the place one drives through to go on holiday in France, Belgian football also passes through the Dutch mind without having any real impact.

Just as Belgium is seen as merely the place one drives through to go on holiday in France, Belgian football also passes through the Dutch mind without having any real impact

When a rivalry is only important to one of two rivals, the reason for this is usually not far to seek: Flemish people will never admit that they look up to their northern neighbours, that they dream of performing equally well, of playing the same role-play on the international stage. Every joke, every taunt, is just a poke from the little brother demanding attention, while the big brother looks the other way, ignoring his sibling.

Even the Belgian Revolution in 1830 was the result of years of frustration in the Belgian provinces with the Northern Netherlands, which – at least in the eyes of many Belgians – was constantly attracting the money and the attention of those in power. The northerners shared the language and religion of the king, while the people in the south remained misunderstood and unappreciated for their individuality and culture. Even after Belgium had shaken off Dutch authority, the Dutch would for centuries be regarded as arrogant know-it-alls, scoffing at the language and customs of those poor farmers from the south. For the Flemish, every joke is still a small, personal act of resistance, whereas the Dutch have long since left that history behind.

Flemish people will never admit that they look up to their northern neighbours, that they dream of performing equally well, of playing the same role-play on the international stage

From that sense of deprivation arises both resentment and the desire to achieve equal success: for example, Flemish politicians have always shown a particular interest in the way their Dutch colleagues approach things. For the past twenty years, they have adopted the Dutch strategy of winning over voters by behaving as sympathetically as possible, much more than on the basis of an election manifesto. In the early 2000s that joviality was flavoured with a socialist sauce, today with a liberal one, but in the end, there is not much difference in policy.

The sports world also has both eyes firmly on the north. Whenever Belgium makes a leap forward in football, hockey or skating, the first question is always: Can we beat the Netherlands? That achievement then serves as the springboard to conquer the rest of the world. Football journalists like to point out that the real beginning of the Golden Generation of the Red Devils, the moment when the young team full of potential world stars clicked together for the first time, occurred at the King Baudouin Stadium in Brussels on 15 August 2012, the evening when the Belgians won a friendly match, 4-2 against… the Netherlands.

Now that we know the deeper background of this historic, one-sided rivalry, it is suddenly no mystery why the animosity of the press and public in Belgium towards the Netherlands has cooled down so much in the past ten years. In that period Belgium has had the better national football team and has taken first place in the world ranking. There is no longer any reason to demand attention, to be regarded as full-fledged – it’s already a done deal. In fact, the relationship has shifted a bit: in recent years the Dutch have started to mock the Golden Generation’s lack of trophies out of envy. The roles in the sibling ‘poking’ rivalry have been reversed.

Belgium back in the role of underdog?

But let’s return to the match on 3 June 2022 at the King Baudouin Stadium. The Orange team was a devastating opponent, the 1-4 final score the heaviest defeat the Red Devils had experienced in years.

After watching the match on Belgian television, I zapped to the Dutch broadcasters, curious to hear their commentary. There was not a trace of gloating. The analysts only discussed the Dutch team’s performance and what it meant for the next game. Belgium was once again passed over as a fleeting afterthought. If it’s true that the 4-2 win over the Netherlands in 2012 heralded the real beginning of the Golden Generation, we may well have seen its official end this year, ten years later.

And let’s be honest: the role of favourite has never suited Belgium. If the imminent departure of this exceptional generation of footballers has one advantage, it is that the Belgians can again behave in the way they used to, once again become the underdog on the international stage and hope for a win at a major tournament every now and then. But, first and foremost, they can once again aim all their barbs at the main goal: beating the Netherlands.