Not many people stop to look at the statue in the middle of Simon Stevinplein in Bruges. It celebrates a brilliant sixteenth-century mathematician born in Bruges who invented the decimal point in mathematics, but also designed a sand yacht that could reach a speed of 35 kilometres an hour.

The illegitimate son of Anthonis Stevin and Catelyne van der Poort, Simon worked briefly as a bookkeeper in Antwerp before setting off on a six-year tour of Europe. Back in Bruges in 1577, he worked for four years as a tax inspector, then moved to Leiden to study science at the prestigious Dutch university.

Stevin discovered the hydrostatic paradox.

Stevin discovered the hydrostatic paradox.© Wikipedia

While in the Netherlands, Stevin began publishing books on geometry, hydrostatics and mathematics. He was the first to use the decimal point in mathematics and also proved that the downward pressure of a liquid depended on the height and base of the liquid and not on the shape of the container.

Stevin eventually struck up a friendship with Prince Maurits, son of William of Orange. He was put in charge of the Department of Water Management, designed several fortifications and introduced the military tactic of opening sluice gates to flood the land.

Simon Stevin built two land-yachts for Prince Maurits. He used them on the beach to entertain his guests.

Simon Stevin built two land-yachts for Prince Maurits. He used them on the beach to entertain his guests.© Wikipedia

But his most remarkable invention was the sand yacht he designed in 1600. The four-wheeled vehicle was fitted with two sails and carried 28 passengers on a two-hour excursion along the beach. Prince Maurits was so impressed that he commissioned Willem van Swanenburgh to produce a large print made from three engraved plates.

Stevin’s influence spread to the United States through his 1585 book on decimals, De Thiende (The Tenth). The English translation, Disme, The Arts of Tenths or Decimal Arithmetike, inspired Thomas Jefferson when he was developing a new currency for the United States. As a result, the ten-cent coin (one-tenth of a dollar) became known as the dime.

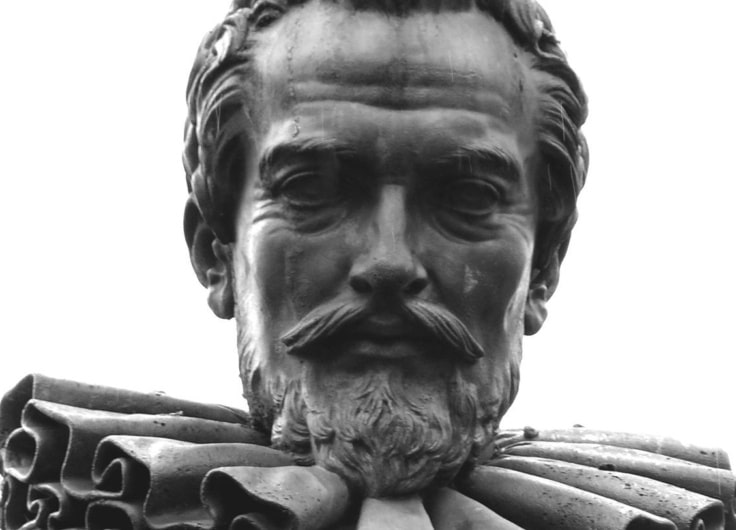

Simon Stevin (1548-1620) statue in Bruges

Simon Stevin (1548-1620) statue in Bruges© Wikimedia

Stevin was virtually forgotten after he died in 1620 and nobody knows whether he is buried in The Hague or Leiden. His reputation was restored in the 19th century when the city of Bruges commissioned a statue of Stevin as the first in a series of public monuments honouring distinguished citizens.

Not everyone approved of the decision. One Catholic politician saw Stevin as a traitor who had helped the Dutch Protestant cause. He added that Stevin was not even that much of a scientist, but the Belgian ambassador in London leaped to Stevin’s defence, describing him as ‘the Belgian Archimedes’.