Dutch-language pop music is making a comeback, as is shown by the programming at Noorderslag and Dutch exports to Belgium. An exploration of Dutch-language music export between Belgium and the Netherlands.

For many years, singing in Dutch was reserved for schlager musicians and cabaret artists. If you wanted to be taken seriously, you had to sing in English. However, as demonstrated by the showcase festival Eurosonic/Noorderslag in Groningen, the stigma that was once attached to Dutch-language music has become entirely a thing of the past: no fewer than 43% of all acts at Noorderslag sang in Dutch, according to the newspaper Trouw.

During the 2020 edition of the festival, a panel of Dutch and Belgian music professionals convened to talk about the challenges that Dutch-language acts face when it comes to touring in the neighbouring country. This debate lines up well with the ongoing project OverBruggen, carried out by De Brakke Grond and DutchCulture, which focuses on difficulties in the cultural exchange between Belgium and the Netherlands (more on this further on in this article).

In this article, Lisa Grob and Albert Meijer study the conclusions of the panel and illustrate them, where possible, with figures from the databases of DutchCulture and Kunstenpunt (Flanders Arts Institute) in Brussels.

Growth of Dutch-language music

The growth of Dutch-language acts may seem unexpected in this time of globalisation. It is increasingly easy to reach a world-wide audience via YouTube and Spotify, so why are more and more artists and songwriters choosing to sing in Dutch?

Panel member Gideon Karting, a booker at Mojo Concerts, sees practical reasons for this choice. More internationalisation means more competition from foreign acts. ‘As a result, the local market becomes more important. On top of that, your own language allows you to target a wider audience. I’m forced to listen to Suzan & Freek at home because of my son – he doesn’t play Katy Perry because he doesn’t understand what she’s saying.’

Another panel member is Kurt Overbergh, artistic leader at the concert hall Ancienne Belgique in Brussels. He thinks that it’s a subliminal counterreaction. ‘I saw Zwangere Guy yesterday: it was so emotional! He sings from the heart, and it’s so much more poignant when you’re Belgian. You understand every word, every hidden meaning. It’s much easier to express yourself in your own language.’

Panel of Dutch and Belgian music professionals on the export of Dutch-language acts in the neighbouring country

Panel of Dutch and Belgian music professionals on the export of Dutch-language acts in the neighbouring country© Nienke Maat

Export of Dutch-language music

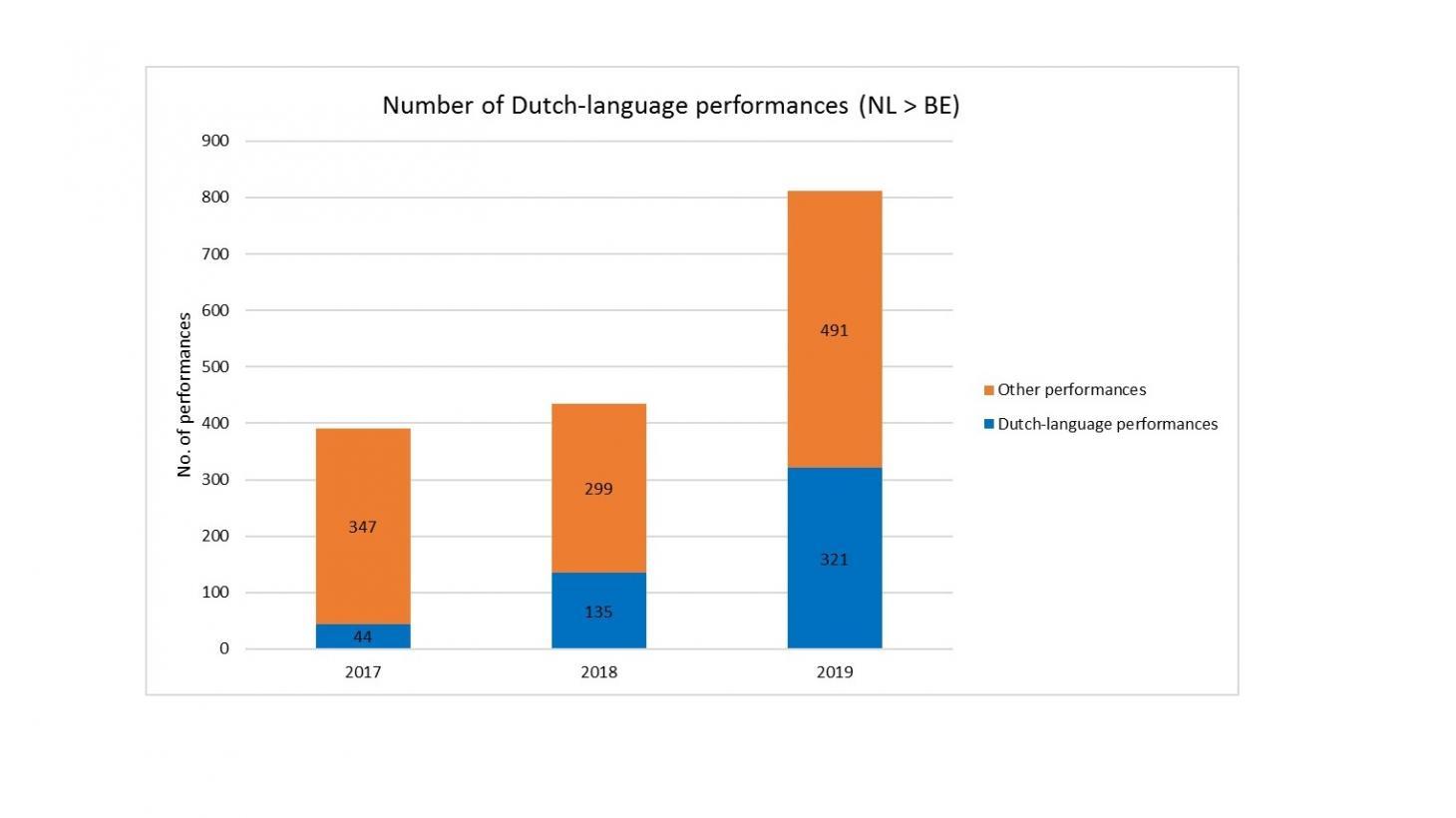

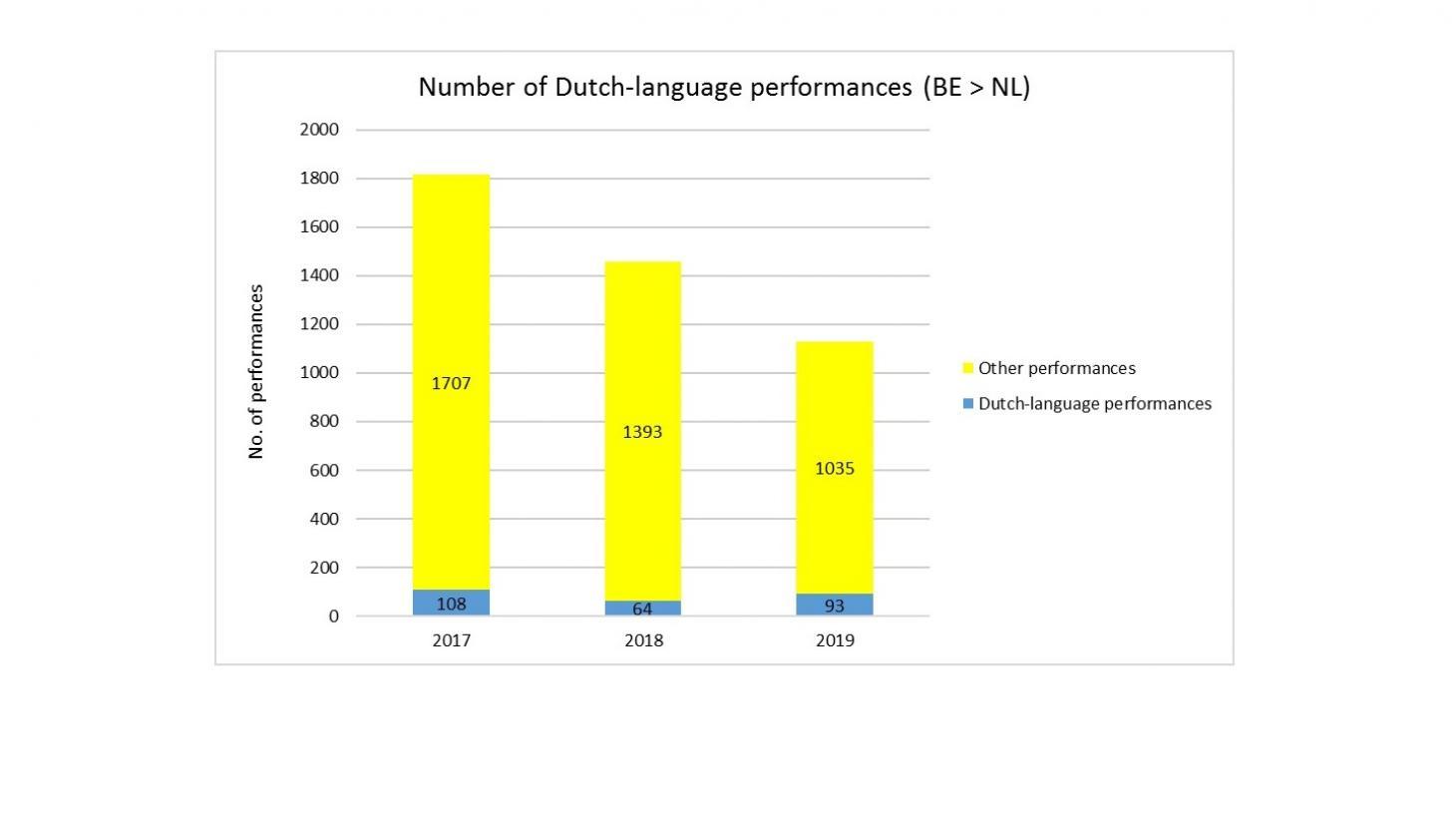

DutchCulture’s figures show that, in the past three years, Dutch-language acts have become a larger part of the total music export to Belgium: while in 2017 only 11% of all Dutch acts in Belgium sang in Dutch, that figure grew to 32% and 40% in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Those are significant numbers, especially if you consider that these numbers include non-language, instrumental acts from classical, jazz and EDM genres. In those same years, Belgian Dutch-language acts formed 10%, 17% and 16%, respectively, of the total number of Belgian acts performing in the Netherlands, according to the figures of Kunstenpunt.*

Number of Dutch-language performances NL > BE

Number of Dutch-language performances NL > BE© DutchCulture

Number of Dutch-language performances BE > NL

Number of Dutch-language performances BE > NL© DutchCulture

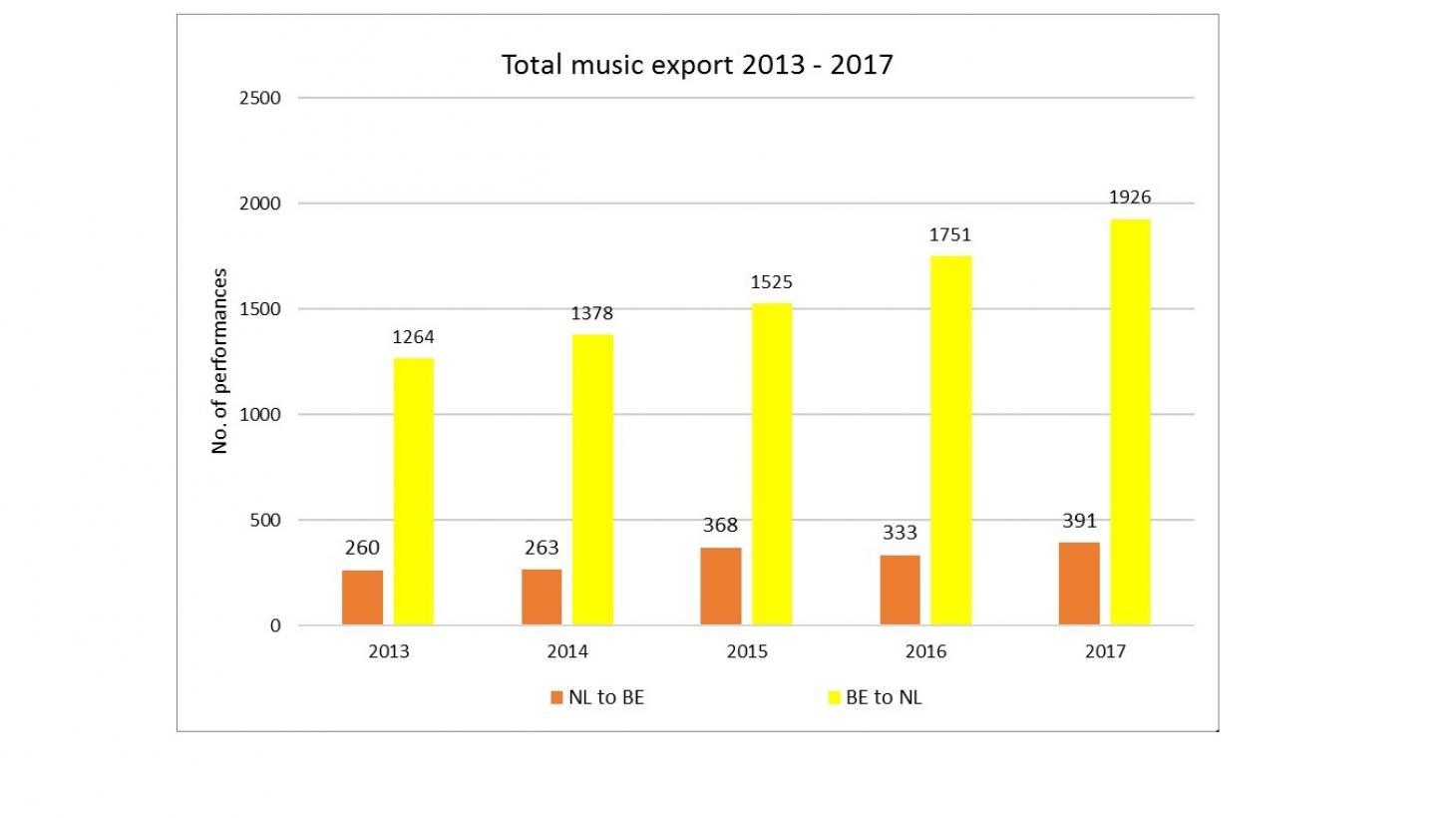

The figures also show that there is more export from Belgium to the Netherlands than from the Netherlands to Belgium. In 2017, Kunstenpunt published a study of the musical mobility between Belgium and the Netherlands in collaboration with Dutch Performing Arts. They counted 7844 concerts by 1310 different Belgian artists (i.e. not only Dutch-language acts) in the Netherlands between 2013 and 2017. That means an average of 1569 concerts per year. In that same period, the figures of DutchCulture show only 1615 performances by Dutch artists in the Belgium, or just 323 per year on average.

Total Music export BE > NL and NL > BE, 2013-2017

Total Music export BE > NL and NL > BE, 2013-2017© DutchCulture

Does this increase in the number of Dutch-language acts crossing the border also mean that the total export of music from the Netherlands to Belgium has grown? It does look that way: in 2018, Dutch artists performed no fewer than 424 times in Belgium; in 2019, that number was 812. This growth is correlated to Dutch-language performances, which have grown exponentially in the same period.

Hip-hop

Where did that growth in Dutch-language music come from? Panel member Stephanie McGuire specialises in Dutch-language music. She works at BMG Talpa Music as a Creative Manager, and in her opinion, we have the success of hip-hop to thank for the rise of Dutch-language music: ‘Dutch urban music has made the language sexier and paved the way for Dutch-language pop songs.’

In 2019, over half of the Dutch-language Dutch artists were hip-hop acts

It is certainly striking that there were quite many Dutch-language hip-hop acts coming to Belgium in 2019: over half of the Dutch-language Dutch artists were hip-hop acts. In the other direction, that proportion is lower, although Dutch-language Belgian urban acts did get a bigger foot in the door in 2019.

Still, the success of Dutch-language mainstream pop remains a significant factor. ‘Artists like Gers Pardoel, André Hazes and Boef are also successful in Belgium,’ says Stephanie McGuire. DutchCulture’s figures support this statement: the “old guard” of Dutch artists, especially, has been finding success in Belgium for quite a while already. Marco Borsato, René Froger, Frans Bauer and Jan Smit are all popular performers in Belgium, as are Spinvis and Wende. In this respect, Dutch-language music has always formed an important part of Dutch acts crossing the border.

Eurosonic Noorderslag

Eurosonic NoorderslagEncourage exchange?

Despite the growth of Dutch music export to Belgium, the number of Belgian acts performing in the Netherland is still greater. During the panel discussion, Kurt Overbergh emphasised that it can be difficult for Dutch acts to gain a foothold in Belgium because it is a complicated country. Ancienne Belgique, for example, is located in Brussels, where only 10% of the population speaks Flemish as their first language. ‘De Jeugd van Tegenwoordig was successful in Brussels because they’re just very good and ballsy, but for other acts it is more difficult.’

Dutch Music Export supports Dutch musicians abroad through grant programmes and showcase events

Should organisations do more to encourage exchange? Panel member Christian Pierre, co-founder of Musickness Artist Management which represents, among others, dEUS, Balthazar and Eefje de Visser, says that there is enough support, despite the imbalance. ‘In the end, it’s up to you to achieve success. More outside intervention would seem a bit fake.’ Gideon Karting is not so sure: ‘If we’re only getting three requests for export to Belgium via Dutch Music Export, then I’d say we need to invest a bit more.’ Dutch Music Export supports Dutch musicians abroad for instance through grant programmes, but also by organising international showcase events for Dutch artists.

In Stephanie McGuire’s view, this panel discussion makes it clear that more could be done to encourage collaboration with Belgium. ‘There is room for improvement in the exchange, for example by setting up joint writers’ camps.’ Kurt Overbergh mentions the experiment carried out by Harry Hamelink, artistic director at Motel Mozaïque, as a good example of an alternative approach. ‘Hamelink organised collaborations between Dutch and Belgian artists in the context of BesteBuren (Good Neighbours): a celebration of cultural collaboration between the two countries. It may not have been organic, but it worked amazingly well – the collaboration between Typhoon and pianist Jef Neve, for example.’

OverBruggen

The 2019 evaluation project OverBruggen, commissioned from DutchCulture and Brakke Grond by the Flemish and Dutch ministries of culture, to jointly investigate the hurdles in the cultural exchange between the Netherlands and Flanders, also studied the imbalance between Dutch acts in Belgium and vice versa. In various lab sessions, OverBruggen interviewed representatives from four sectors (music, visual arts, performance arts and design & architecture) about the obstacles they encountered when attempting to work or collaborate across the border.

Flemish bands were said to be more experimental and more focused on the music than on ‘the presentation’

In the lab session on music in September, the Dutch participants did indicate that Dutch artists have trouble gaining a foothold in Flanders. The reason they believe is that Belgium generally has more attention for music from the own country, while in the Netherlands, everything foreign is seen as interesting. Furthermore, Flemish bands were said to be more experimental and more focused on the music than on ‘the presentation’. In this context, the Dutch political emphasis on entrepreneurship was also criticised. For Dutch musicians, the marketing concept takes precedence over the actual music, due in part to the lack of subsidies for booking agents or business support in general.

Another problem in the exchange that became apparent during the session is that musicians are barely aware of how the infrastructure in the other country works. Increasing knowledge about this, for example through information and networking meetings, could have a positive effect on the exchange. In this regard, cross-border initiatives such as the abovementioned Motel Mozaïque, as well as GrensGeluid and the double bills of Brakke Grond and EKKO (evenings with two main acts: one Flemish, one Dutch) were praised.

In this lab session, too, hip-hop was mentioned as the major exception: for these artists, the Flemish market is much more accessible. In fact, the problem seems to be reversed here: without a Dutch hip-hop artist at their side, Flemish hip-hop artists are barely taken seriously, even in Flanders itself.

The success that young Dutch-language hip-hop artists have been having in Belgium in these past two years is quite remarkable, to say the least. Nevertheless, in 2019 we also saw Dutch-language acts from other genres make their mark, such as Eefje de Visser and Merol. Time will tell whether this development of young Dutch-singing artists will continue in both Belgium and the Netherlands.

*The percentages regarding 2017-2019 in both the Netherlands and Belgium were calculated based on figures from DutchCulture and Kunstenpunt, but Dutch-language acts did not constitute a separate category in either dataset. The Belgian export dataset for 2017 from Kunstenpunt’s Have Love Will Travel database showed a different total number of acts than the study published by Kunstenpunt over 2013-2017. Finally, some artists performing in different languages, such as Wende, Spinvis and Anouk, were counted as Dutch-language acts. The percentages should therefore be regarded as an estimate, not as exact figures.

This article was previously published on DutchCulture.