”Slaughtered” for the Exam: Stories From a Teacher of Dutch as a Second Language

Dutch is a beautiful language. But it can seem difficult and sometimes downright illogical to foreign-language newcomers. How do you inspire them to love our language? Joachim Stoop, a teacher of Dutch as a second language for twenty years, shares his experiences.

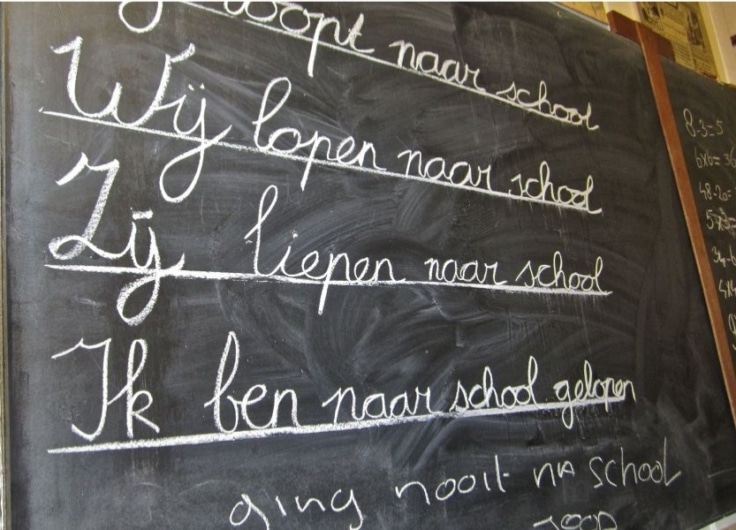

Goedemiddag! I write the word (good afternoon) in separate letters on the board, turn to the class and gesture for everyone to pronounce it together. “Goedemiddag”, the brand-new students repeat hesitantly. The first lesson in the beginner level of Dutch as a second language (NT2) for foreign-language newcomers is their very first (school) encounter with the language – a tentative toe dipped into the cold, still waters of Dutch language immersion.

Before entering the classroom, I thought back to a study day when a colleague tried to teach us some basic Chinese sentences, speaking only in Chinese. With no prior knowledge, I was thunderstruck. Or rather: 我聽到了雷 聲!

With that Chinese experience in mind, I now stand in front of a class of newcomers. Go slow, Joachim. You need to e-nun-ci-ate exaggeratedly. Don’t jumble your words, or worse: your sentences. Use your best handwriting on the board. Draw, if you must. Gesture like a seasoned mime.

The world has gathered in this classroom, and this global mishmash is working together towards the same goal: mastering a new language.

The world has gathered in this classroom, and this global mishmash is working together towards the same goal: mastering a new language.© Joachim Stoop

If you could bottle the scent of nerves, then a litre of essence de stress has been poured into this room. Just imagine: after twenty, thirty, forty years, you’re back in school, in a country you never stopped to consider while tracing your finger over a map: “This is where I’m going to build my future.”

Polish Sunday drivers

Only later in the semester will I get to discover the life stories behind their faces: the Polish doctor’s assistant who moved to Belgium because she could earn more as a cleaner here; the dainty woman from Thailand who married an older white man and moved with him to his homeland; the Ethiopian taxi driver who, after a quarter of a century, finally saved enough for a one-way ticket to Europe; the Ukrainian mother of three, whose husband is fighting on the front lines; the Syrian who checks his phone forty-six times per lesson to see if anything terrible has happened in Aleppo; and the Pakistani pharmacy assistant who delivered medicine to hospitals across Lahore. We often cross paths as he dashes through Antwerp’s unfamiliar streets on a scooter, delivering pizzas. The world has gathered in this classroom, and this global mishmash is working together towards the same goal: mastering a new language (een nieuwe taal onder de knie krijgen – literally to get something under your knee, meaning to master something), so that one day, they’ll be able to understand such expressions.

If these beginners complete four modules, they might end up in my class again. At that level, I’ll start each lesson with a ‘word or phrase of the day’. Quirky, witty terms that are unique to Dutch but aren’t readily found in a standard textbook: like kip zonder kop (like a headless chicken = acting haphazardly), ezelsbruggetje (donkey’s bridge = a mnemonic device), huisjesmelker (house milker = a slumlord), over koetjes en kalfjes praten (talking about cows and calves = talking about trivial things) and verbs like ijsberen (polar bearing = to pace) and muggenziften (mosquito sifting = to nitpick). I first ask the students what they think the phrases might mean. Although most miss the mark completely, their explanations are often more logical than the correct answer. A Rwandan student thought a kettingroker (chain smoker) experienced smoking excessively, as if a necklace were too tight. Hangjongeren (hang youth = loitering teens) turned out to be teens who spend the whole day lounging on the couch. And aren’t concentratiescholen (concentration school = schools with a high concentration of students from non-Western immigrant backgrounds or disadvantaged socio-economic environments) places for students who can focus extremely well? I learned that Sunday drivers exist on Poland’s roads too, and that people everywhere count sheep to try and fall asleep.

Are 'concentratiescholen' places for students who can focus extremely well?

Back to my beginners group. For them, all these abstract words are still toekomstmuziek (future music = far away). I write my first name on the board: Welkom in de cursus Nederlands! Ik heet Joachim. (Welcome to the Dutch course! My name is Joachim.) Then, I write the word vraag (question), the symbol ? and 1+1=?. I say: “Hoeveel is één plus één?” (How much is one plus one?). Someone answers: “Two”. Good! 1+1 = question, 2 = answer. The first question in Dutch is: Hoe heet jij? (What’s your name?). I write it on the board and ask the nearest student.

“My name is Mamadou.”

“Dag Mamadou. Aangenaam. Nu jij: aan-ge-naam.” (Hello Mamadou. Nice to meet you. Now you: aan-ge-naam.)

We shake hands. Mamadou now has to ask the same question to his neighbour, and off we go.

Cows, lots of cows

During the twenty years I’ve been teaching Dutch to newcomers, there are two questions I often hear. The first: “Are you really only allowed to speak Dutch in class?” Absolutely! When learning a language, one needs to know its building blocks and understand how they fit together. Ideally, this happens exclusively in Dutch. The teacher guides this deep immersion into a new language by instructing, guiding and motivating.

It’s essential to have an array of fun, stimulating exercises: we hold class discussions with statement games, students promote their favourite film, book or TV series, or tell a true story to make the teacher and classmates smile (or laugh). Another exercise involves listing the positive and negative traits of Belgians. And why not have them write a poem? The aim is always to stimulate their imagination so that they can explore the boundaries of their budding vocabulary.

I teach the imperative in a fun way with the song Pa by Doe Maar: “Stel je netjes voor, eet zoals het hoort en zeg u u u u.” (Introduce yourself properly, eat as you should, and say u u u u.)* And when I ask what image they had of Belgium before coming here, some say “niks” (nothing), while others mention Rubens, Stromae, chips, chocolate, beer, waffles, Brussels and cows, lots of cows. No, Mr. Dewinter and Mr. Wilders. Answers like werkloosheidsuitkering (unemployment benefits), losbandige vrouwen (promiscuous women) and straffeloosheid (impunity) are never included. I teach the conditional with thought-provoking questions. “What would you do if you were the Belgian Prime Minister?” Maria: “I would give everyone their immigration papers.” Or: “What would you change about your appearance if you could change one thing?” As I read that question, I see the one-armed Syrian sitting there with his eternal smile and realise that I have made a blunder. To my great surprise, he raises his only arm and answers confidently: “My nose!”

Friendly veggies

Meanwhile, the absolute beginners in my class are ready for the next questions in their very first Dutch lesson: “What country are you from? What language do you speak? Where do you live? How do you come to school?” Inevitably, someone will answer: “I come to school with the foot (met de voet).” Whereupon, I pretend to take my foot off and walk with it under my arm. Almost the entire class laughs. Fear and nerves fade from their faces. Humour is often the little hammer that breaks the ice.

Dutch is full of exceptions, like te voet (on foot). I’m still amazed at how difficult and downright illogical our language can be. Sentences with four consecutive infinitives, words that you can endlessly string together and the many variations around a single verb. Take the distinctions between slapen (to sleep), over slapen (to oversleep), uitslapen (to sleep in), zich uitgeslapen voelen (to feel rested), doorslapen (to sleep through), bijslapen (to catch up on sleep) and inslapen (to fall asleep or put to sleep). With the last one, of course, if you’re not careful, you could be talking about a lethal injection.

The vast majority study Dutch because it’s essential for work, social interaction, and all sorts of administration or communication with their children’s school.

The vast majority study Dutch because it’s essential for work, social interaction, and all sorts of administration or communication with their children’s school.© Joachim Stoop

Although spelling is subordinate to sentence structure in a course of Dutch as a second language, small mistakes can lead to major blunders: the Ministry of Foreign Bags (Zakken instead of Zaken). I’m going to rob a pizza (bestelen instead of bestellen). I’m a gardener, so I work with bombs (bommen instead of bomen). How much is the monthly prostitute? (hoer instead of huur, meaning rent). I’m slaughtered for (geslacht voor) for the exam (instead of geslaagd voor, meaning passed). Much bettersheep (beterschaap instead of beterschap, meaning get well soon). And friendly veggies (groentjes instead of groetjes, meaning greetings).

Enthusiasm is not enough

The second – more rhetorical – question I’m most often asked about my profession is: Isn’t that a difficult target group, with so many different nationalities in one classroom? No, on the contrary! A more pertinent question would be: Is there any group of students more grateful and motivated than these newcomers? At the end of the course, my colleagues and I are often showered with gifts (albeit after the results have been handed out): from tacky vases to perfume, from gift vouchers to, occasionally, a bra in a generously estimated size.

The vast majority study Dutch because it’s essential for work, social interaction, and all sorts of administration or communication with their children’s school. Without a shared language, they know they’re in a tough situation. What I still find difficult is handing out a poor report to motivated students who consistently attend classes – even on top of family and work responsibilities – but cannot compensate for their limited language skills with motivation and diligence. I know: c’est la vie. But in a society where the focus is more on results than intentions, it’s painful, especially for newcomers who often have to climb the social ladder from the bottom rung.

On the other hand, I have to be realistic: almost everything here revolves around language. Language and cognitive skills orbit our working world like satellites. If you fall short in that area, no matter how great your enthusiasm, it seriously limits your opportunities.

In the same boat

In a society full of quick and easy judgments, working as a teacher of Dutch as a second language is refreshing. Even after twenty years, I still notice my own prejudices. And sometimes, those prejudices are confirmed, like with the Russian student, whose writing exam, where he had to introduce himself in detail, consisted of exactly one sentence: Ik het (sic) Vladimir. (My name is Vladimir.) One evening, I was sitting on a terrace when he suddenly appeared before me with his smartphone, speaking into it in his native language. He showed me the translation: “I am afraid I have not passed. I want to buy exam. How much euro for diploma?” At such moments, it becomes clear that prejudices work like darts: you miss the bullseye nine times, but only remember the tenth, perfect shot.

In a society full of quick and easy judgments, working as a teacher of Dutch as a second language is refreshing

I’d rather think back to an Afghan Muslim woman who, during an oral exam, sat before me, covered from head to toe, and surprised me with her answer to why she came here: “Because women in my country have fewer opportunities. Here in Belgium, it’s modern, and I’m allowed to work.”

I see the huge diversity of people, cultures, religions and ages (ranging from eighteen to eighty) who sit in our classrooms each year as a welcome antidote to bitterness, polarization and right-wing populism. Nowhere do I feel more peace and hope than among this cosmopolitan bunch, this battered mosaic of people with their hearts in their homeland but their eyes on the future.

I see the huge diversity of people, cultures, religions and ages who sit in our classrooms each year as a welcome antidote to bitterness, polarisation and right-wing populism

I’ve been able to witness how a Hasidic Jew sat next to a Palestinian, how Shiites worked with Sunnis on assignments and how a friendship blossomed between a Russian and a Ukrainian. What divides them at home can, due to common roots elsewhere, actually bring them together here. On the most basic, common level of a classroom, living together works surprisingly well. Perhaps because, despite the extreme diversity, they’re all in the same boat.

Apart from that vast diversity, it’s refreshing to discover that certain things are the same in every classroom around the world: the question “Will this be graded?” when you hand out an exercise on paper. The entire classroom mutters nooo and ohhh when you answer affirmatively. The face of a student caught red-handed while cheating. The reaction in the classroom when you say, “Cheating is pointless because you’re smarter than your neighbour.” Everyone looks right and left, stops to think and bursts out laughing.

The first lesson has now drawn to a close. The essence de stress has dissipated. The newcomers head home in good spirits. And now you: 你叫什麼名字?

*U is the formal form of the personal pronoun you.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.