Slavery Was of Major Importance to the Dutch Economy

Dutch historians have long worked on the assumption that the significance of Atlantic slavery to the Dutch economy was marginal. In an article published at the end of June this year in the Flemish-Dutch magazine TSEG / Low Countries Journal of Social and Economic History the authors show that this assumption is incorrect.

In 1770, activities based on Atlantic slavery made up as much as 5.2 % of the Dutch Republic’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). For the Netherlands’ most prosperous and powerful province, Holland, the figure was as high as 10.36 %. The result has led to fierce media debate today, and has been broadly received as an important correction of the dominant self-image of the Netherlands’ history with respect to slavery.

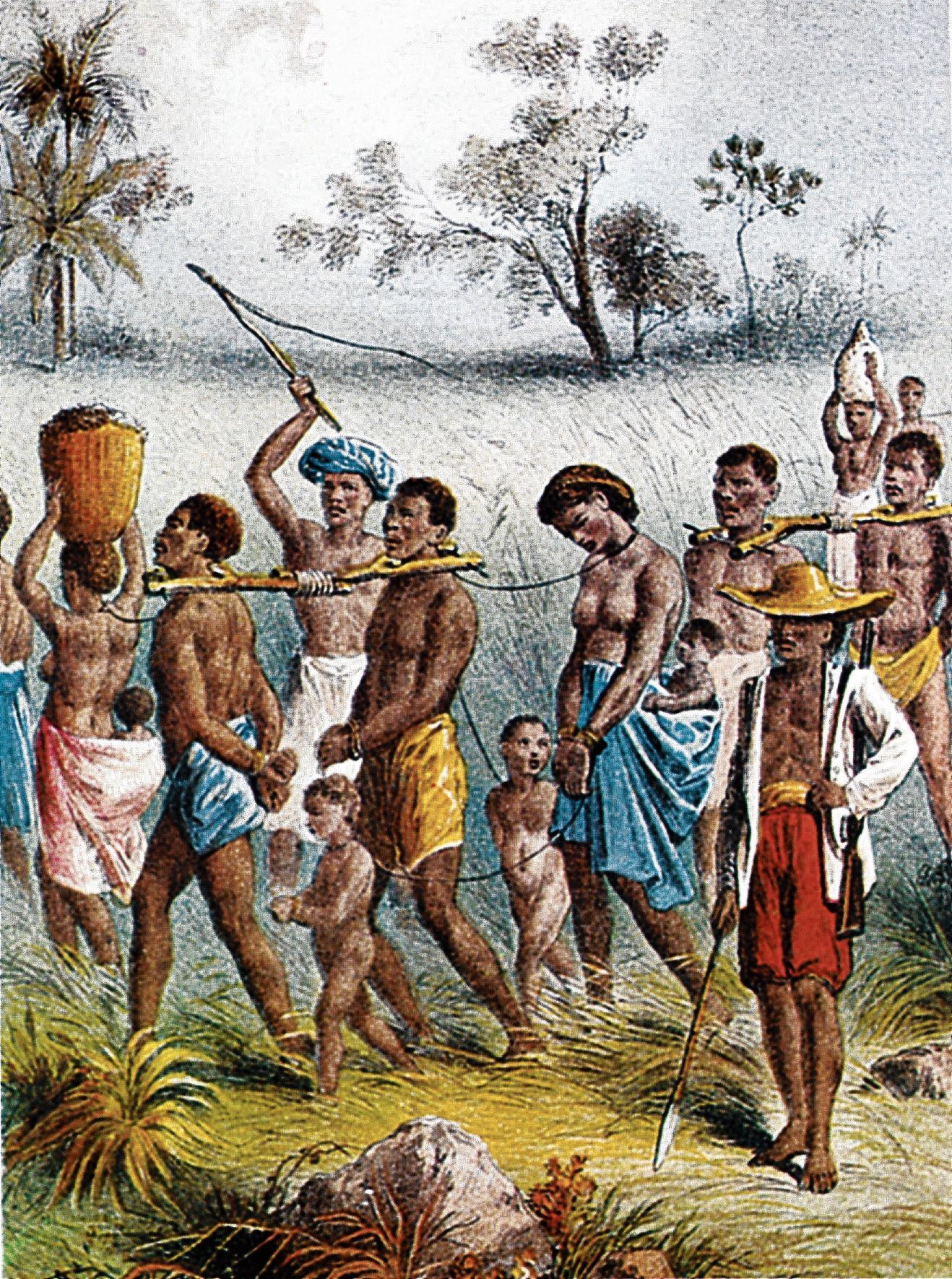

Group of African captives being taken to a slave market

Group of African captives being taken to a slave market© Wellcome Trust

The numerical results are the end product of a large-scale study of the significance of the Atlantic slave trade for the Dutch economy in the second half of the eighteenth century. The project started in 2014 and was conducted by researchers at the International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam), the Vrije Universiteit and Leiden University. It consisted of three separate studies. The first concerned the slave trade from the two cities of Walcheren, Middelburg and Vlissingen (Gerhard de Kok).

A second study, still in progress, looks at the international supply chains for sugar and coffee produced by slaves (Tamira Combrink). The third study focuses on the role of banks and insurance companies involved in slavery (Pepijn Brandon and Karin Lurvink). The aim of the synthesis is ultimately to offer an extensively supported calculation of the weight of activities based on the Atlantic slave trade in GDP.

Are the estimations realistic?

Other countries have also attempted to measure the importance of slavery, or of colonial trade in general, in relation to the size of national economies. In Great Britain, the main player in the Atlantic slave trade in the eighteenth century, this has in fact been the subject of serious academic debate for decades. Viewpoints have varied from the claim that slavery was one of the most important sources of prosperity behind the industrial revolution, to the idea that colonial trade was of very marginal significance for the development of the national economy.

Slave shackle, anonymous, 1700 - 1899

Slave shackle, anonymous, 1700 - 1899© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Such deep discussion has largely been absent from other European countries. Most economic historians have accepted the conclusions of the British authors who state that the economic significance of slavery was limited. A core factor was the tendency to base the question of the economic importance of slavery exclusively on the profits of the slave trade, without considering the far more extensive trade in the goods produced on the slave plantations.

In the Netherlands, too, there has been a tendency to trivialise the question. In recent years, however, attention for the subject has substantially increased, as it has for example in the US, England and France. In this context the question also arose as to whether the existing rough estimations of the economic significance of slavery were realistic. The development of the economic historiography of the Netherlands was also a reason to ask questions on the matter.

New data on the extent of the Atlantic trade underlined the fact that Dutch traders also took full advantage of the rise of a European mass consumer market for sugar and coffee produced by slaves in the Atlantic region. Taking that into account, in the second half of the eighteenth century the Atlantic trade even outstripped the Asian spice trade by the Dutch East India Company (where in fact there was also large-scale slavery).

A refinement of existing estimations for the total scope of the early modern Dutch economy by Jan Luiten van Zanden and Bas van Leeuwen also made it possible to examine the importance of each individual sector of the Atlantic trade flows far more precisely.

Slavery Memorial in Rotterdam

Slavery Memorial in RotterdamMore than a marginal contribution

The calculation process, and the basis for the many estimates at its foundation, are set out in an extensive English-language numerical appendix on the website www.tseg.nl. The article itself will also be published in English in the coming year. For now, the following points summarise the main results:

1. At 5.2 % of national GDP, and even more than 10 % of the GDP of the province of Holland, the contribution of Atlantic slavery to the Dutch economy in 1770 was not marginal but substantial. Extrapolations also allow us to show that 1770 was a representative year for the second half of the eighteenth century. In a large number of years the percentage was therefore higher.

2. The percentages mentioned came substantially (more than 70 %) from international trading houses and shipping companies. More than 19 % of all goods that entered or left Dutch ports in 1770 (expressed in economic value) was produced on slave plantations in the Atlantic world.

3. It was not the slave trade itself, but the trade in goods produced by slave labour that formed the most important source of income for the Dutch economy. The slave trade was only the first step in a much broader economic system that revolved around the work the slaves then carried out, year after year, on the plantations.

4. Dutch traders did not only profit from goods produced on slave plantations in their own colonies in the Atlantic world: until the end of the eighteenth century the Republic functioned as a distribution point for coffee, sugar and tobacco from the entire Atlantic region, with a major role for France’s most important slave colony, Saint Domingue (later Haiti).

5. The immense trade flow from the Atlantic region in that single year 1770 was based on as many as 120,000 entire human years of forced labour on the plantations. This took place in a period in which the Dutch labour force consisted of at most a million people.

The spectacular growth of activities based on Atlantic slavery compensated for the stagnation or decline in many other sectors of the Dutch economy

The majority of the debate in the media resulting from our findings has not focused on these kinds of technical issues, but on its broader significance for dealing with the Netherlands’ historical involvement in slavery. There were of course the predictable reactions from those who don’t care whether slavery contributed 0.5 %, 3 %, 5 % or 10 % to the economy, and who have already concluded that the contribution was very limited. In purely quantitative terms, however, it is a proportion that cannot be ignored. By way of comparison, according to recent research at Erasmus University Rotterdam, the port of Rotterdam, including all logistical industry and business services involved, contributes 6.2 % of the Netherlands’ current GDP.

What is even more important is that figures such as these only really become meaningful in combination with a broader analysis of the structure of the economy. The spectacular growth of activities based on Atlantic slavery compensated for the stagnation or decline in many other sectors of the Dutch economy at the end of the eighteenth century.

In particular the big trade cities such as Amsterdam and Rotterdam managed to continue and even better position themselves in international commercial networks by taking advantage of the forced labour of many thousands of slaves in the Dutch, French and British plantation colonies. Trade in sugar, coffee and tobacco created new connections between the Republic and the European continent, particularly through the growing Rhine trade in colonial goods. This was highly significant for the long-term development of the Dutch economy.

National Slavery Monument in Amsterdam

National Slavery Monument in AmsterdamAn important result of our research is that we need no longer stare blindly at the relationship between slavery and the industrial revolution. The discussion should be much broader, because slavery had a big impact on European trade flows and models of finance, consumption patterns and economic policy. The new wave of slavery research therefore not only has implications for dealing with the national history of slavery, but also for the way we view the economic history of Europe and the world.