Spotted: The Real Hercule Poirot

Who did Agatha Christie have in mind when she gave life to the iconic detective, Hercule Poirot, in 1920? As it turns out, it is quite likely she was thinking of a retired Belgian police officer who had fled to the UK during World War I.

For their project on Belgian refugees in the UK during World War I, the Amsab-Institute of Social History in Ghent started looking for testimonials. Meeting Royal Navy Commander Michael Clapp was one of the most memorable moments in their search. While he was researching his genealogy, Clapp became fascinated with Jacques Joseph Hamoir, a former gendarme, who, together with his son, had fled from Herstal to the UK after the war had broken out.

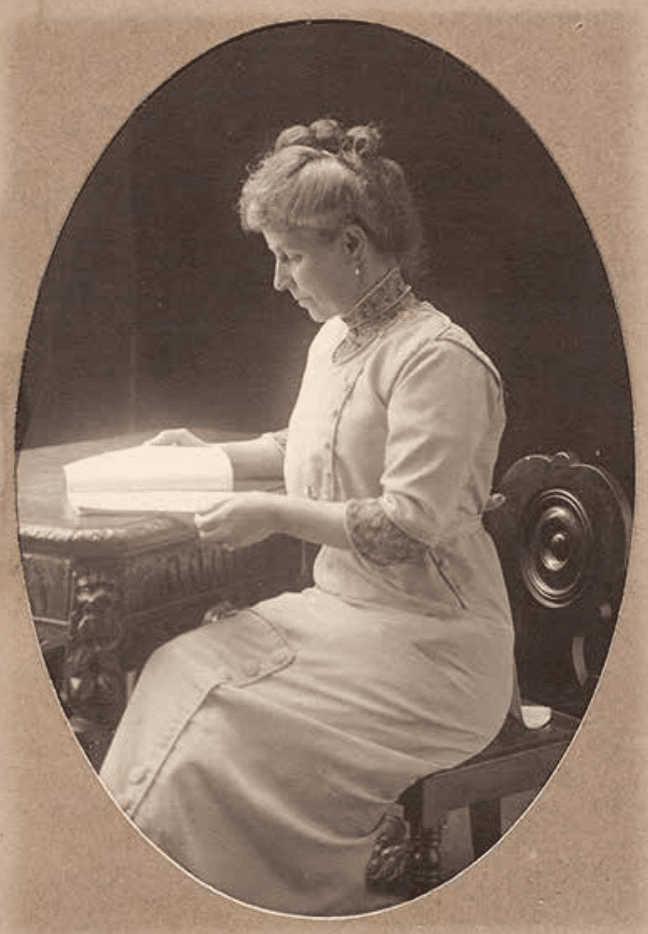

Agatha Christie in Torquay

Agatha Christie in Torquay© Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

Clapp’s grandmother took Hamoir in in Exeter, a small town in the southwest of England. Michael Clapp discovered that Hamoir might have been the inspiration for one of Agatha Christie’s most beloved characters, i.e. Belgian private detective Hercule Poirot.

Allow me to introduce… Poirot

During one of the most important stages of her life, Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller (1890-1976), queen of crime writing and the best-selling author of all time – only outsold by the Bible − lived in Torquay, a sophisticated seaside town on the Devon coast. That part of the country was referred to as the ‘English Riviera’, because of its micro-climate, rolling green hills, white houses dotted along sloping streets and palm trees. The area inspired many of Christie’s novels, and in a lot of them, she used it as the backdrop. The town would later rise to fame thanks to the television sitcom Fawlty Towers, which was set there.

Agatha and Archie Christie on their wedding day in 1914

Agatha and Archie Christie on their wedding day in 1914Agatha was the third child of wealthy American stockbroker Frederick Alvah Miller and British Clarissa ‘Clara’ Margaret Boehmer. Her father passed away when she was just eleven years old. When she turned sixteen, shy Agatha, who had been home-schooled until then, left for a Paris boarding school to further develop her musical skills. Afterwards, she tried to make it as a professional pianist and singer – unfortunately, she was not successful.

In 1912, she broke off her engagement with Reggie Lucy, as she had fallen in love with Royal Flying Corps pilot Archibald ‘Archie’ Christie. They were married in 1914, on Christmas Eve, after which Archie had to leave for France for Royal Flying Corps duties. Even during their engagement, Agatha had already turned her back on her sheltered life to work as a volunteer nurse with the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD).

In 1916, in between Archie’s military leaves and her work as a nurse, she wrote The Mysterious Affair at Styles, in which we meet the impeccably dressed retired Belgian police officer Hercule Poirot, with his waxed moustache and his “little grey cells” for the first time. In the Styles case, a VAD nurse, Cynthia Murdock, features as well. In that same year, Agatha had a bad bout of the flu. As soon as she had recovered, she quit her job as a nurse and took up work at the hospital dispensary, where her friend Eileen Morris was in charge. What she learned at the dispensary about cooking up poison and what its effects are triggered her imagination and provided a source of inspiration for her first whodunit.

In Christie’s very first novel, Poirot had just arrived in the UK. He and a few other Belgian refugees reside in the village of Styles St. Mary. Hasting, a captain who was injured during the war, enlists Poirot’s help when Mrs Inglethorp, who helped Belgian war refugees seeking refuse in Styles St. Mary, dies under suspicious circumstances. However, the manuscript would only be published in 1920, after having been met with dozens of rejections.

The UK was home to 250,000 Belgian refugees during World War One, the largest single influx in the country's history.

The UK was home to 250,000 Belgian refugees during World War One, the largest single influx in the country's history.© Flickr / Paul Townsend

Agatha Christie did not actually remember how she created this odd little man. In her autobiography, she writes: ‘I was thinking about our Belgian refugees… Why not make my detective Belgian, I thought…? Yes, well, that is how I ended up with a Belgian sleuth… Hercule. Hercule Poirot. And that was that; he had arrived, thank heavens.’

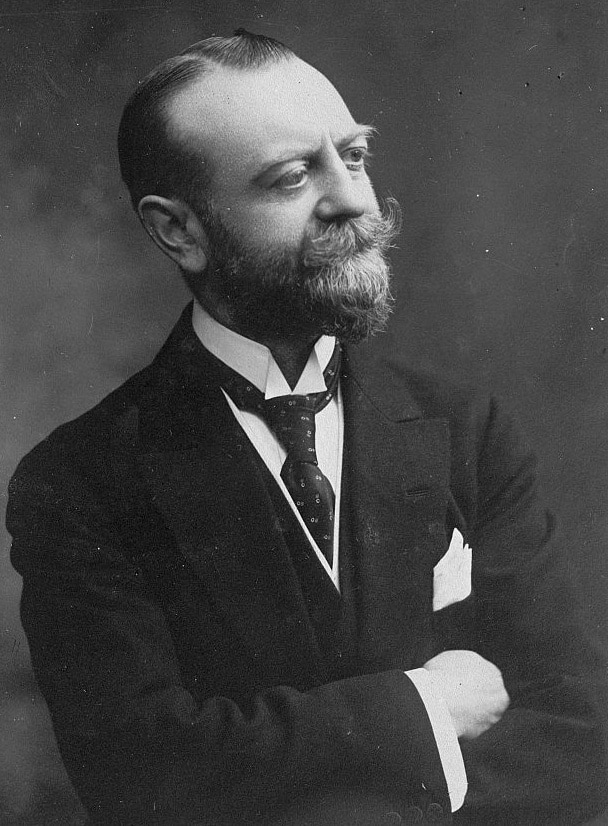

The Belgian war refugees lived in Tor, a borough in Torquay, and Agatha would see them on a daily basis, not just out and about around town, but also in the Red Cross hospital where she worked. According to some accounts, she took inspiration for Poirot’s impeccable look from a newspaper picture of Brussels mayor Adolphe Max.

Adolphe Max, mayor of Brussels

Adolphe Max, mayor of BrusselsTaking precision to the extreme, immodest and slightly eccentric Poirot evolved into a legendary character who would go on to solve myriad murder mysteries, including Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and Death on the Nile (1937). Agatha, however, had a love-hate relationship Poirot and his quirks, to the extent she wrote Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case as soon 1940. Nevertheless, the manuscript was stored in a safe and was not published until 1974, after which, sure enough, Poirot was honoured with an obituary in The New York Times.

Agatha dedicated her first novel to her mother with whom she was very close. Therefore, her mother’s death in 1926 came as quite a shock to her. On top of that, Archie filed for divorce that same year. Soon after, the whole of the UK was captivated by her disappearance. After about three weeks, she was found in a small hotel, where she was registered under Nancy Neele, her husband’s mistress’ name. Agatha told the police she suffered from amnesia. Even after she had married her second husband, archaeologist Max Mallowan, in 1930, she kept the last name ‘Christie’.

From Hornais to Hamoir

In 2008, 32 years after Dame Agatha’s passing, retired Royal Navy Commander Michael Clapp’s brother left hem two worn leather suitcases. Among other things, they contained a small booklet with a black cover that had once belonged to Michael’s grandmother, Mrs. Alice Graham Clapp. She was involved with the accommodation of war refugees in Exeter. In the booklet, you can read the names of some 500 Belgian refugees, most of which had been scribbled down by the refugees themselves, as well as their ages, professions and home addresses. In the column next to it, the location where they would be given refuge and the name of the person who would assist them during the process was jotted down.

Alice Graham Clapp

Alice Graham Clapp© Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter

At the bottom of page 41 in the notebook, you can read the name of a former gendarme. Michael Clapp reads the name of the 57-year-old man as ‘Hornais’. He arrived in Exeter on 18 January 1915. He came from Herstal and was joined by his 17-year-old son Lucien.

Michael Clapp was initially intrigued by him because he was given refuge with a Mrs. Potts-Chatto on 13 February 1915. She lived in a house in Torquay called ‘The Daisons’, near ‘Ashfield House’, where Agatha Christie’s family lived. The house has since been demolished and there are no members of the Potts-Chatto family left in the area, but the street is still called The Daisons.

In Torquay’s municipal museum, the archivist dug up a local newspaper featuring an article about a fundraiser organised by Mrs. Potts-Chatto on 6 January 1915 in order to collect money and clothes for the refugees. Agatha played the piano at that event. Considering our former gendarme did not arrive in Exeter until later, he could not have been at the fundraiser. It is, however, extremely likely that Agatha’s family knew the Potts-Chattos and that they were acquainted with Michael Clapp’s grandmother.

Still, Agatha and this Mr. ‘Hornais’ could have met at a later stage. Furthermore, the fact that the booklet does not mention any other gendarmes, and that he was one of the very few refugees who was sent to Torquay, increases the possibility of Agatha actually meeting him.

This mysterious Jacques Hornais became much more tangible after Michael Clapp had told his story to Bruno Waterfield, a Brussels correspondent for the Daily Telegraph. He decided to get in touch with Herstal municipality. Its local archivist was able to confirm that a former gendarme, born in 1858, and his son did indeed leave for the UK during the Great War. His name, however, was not Hornais, but Hamoir. Moreover, he confirmed that his wife Marie Celine Hallet, and their daughter Yvonne, had initially stayed behind in Herstal.

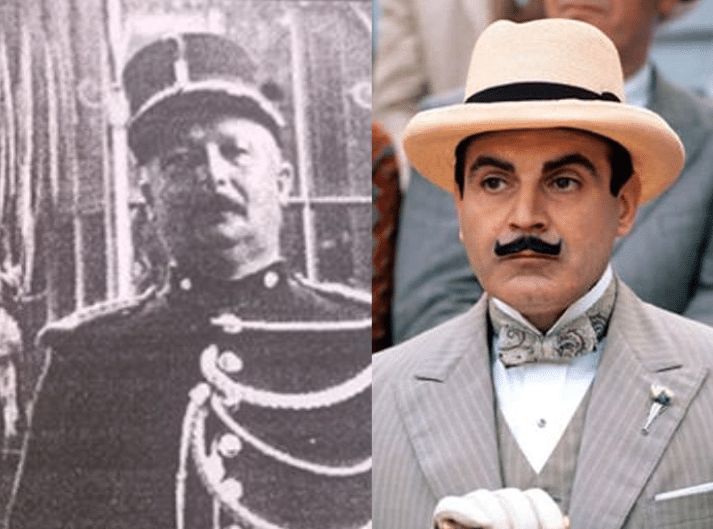

Belgian policeman Jacques Joseph Hamoir and David Suchet as the fictional detective Hercule Poirot

Belgian policeman Jacques Joseph Hamoir and David Suchet as the fictional detective Hercule Poirot© Archives Herstal

It just so happens that Herstal’s archivist, Isabelle Le Ponce, had actually published a book on the gendarme, which featured a picture of Hamoir. In the picture we see a small man, who seems quite cheerful and lively. Isabelle Le Ponce added that Hamoir had left the gendarmerie when the war broke out and became an officer in the Belgian army. After he had fought in several battles, he was injured and ended up in the UK. Jacques was believed to return to Herstal around 1920. He was offered a medal for his bravery as an officer. His son Lucien would never return to Belgium. He drowned at sea in Duporth Beach, near St Austell, where he was taking a swim on 22 July 1916. Both Belgians and Cornwall residents, where the Hamoirs had moved to in the meantime, attended his funeral. It appeared Lucien was extremely well-loved and had also acquired some name as a musician. His mother and sister attended the funeral as well. It is not clear when they fled Belgium, nor who took them in. Jacques Joseph Hamoir died in 1944. He lived to be 86.

We will never be completely sure whether Hamoir was truly the inspiration – or, at least, in part – behind the character of Hercule Poirot. Nonetheless, the story of this former gendarme remains worth telling…

This article first appeared in Brood & Rozen 2016-1, published by the Amsab-Institute of Social History.