Holocaust Past Meets Modern Amsterdam in Steve McQueen Documentary ‘Occupied City’

12 Years a Slave director Steve McQueen takes us on an amazing, meditative journey through Amsterdam in Occupied City. His documentary shows how the Second World War has shaped the contemporary face of the Dutch capital.

The video artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen, originally from London, and Amsterdam-based art journalist and historian Bianca Stigter had only just met when they went for a walk together through the Dutch capital 27 years ago. After asking Stigter what the meaning of a monument was that they were passing, McQueen was shocked. It was here that a group of Dutch prisoners were shot during the Second World War as reprisal for a Nazi soldier killed by the resistance. For McQueen, who grew up in an unoccupied city, this was chilling. Suddenly he became aware of how much recent history had left its mark on Amsterdam as an occupied city. He also realised how in “the city of Anne Frank” some stories had been pushed to the foreground and others to the background.

Years later, when their children went to secondary school in Amsterdam, Stigter worked on her book Atlas of an Occupied City: Amsterdam 1940-1945 (2019). In it, she alphabetically maps out what happened at around two thousand addresses in the city during its occupation. McQueen was struck again – this time because of how those stories were embedded within places that featured in their personal, everyday lives.

For example, the history of the school buildings where his children walked around every day. Prisoners were interrogated and tortured by the SS in the basement of his daughter’s school, a place where children now park their bicycles and store backpacks in lockers. The headmaster of the school where his son studied was deported to a concentration camp because he had opposed the deportation of Jewish pupils.

The mental image of how the innocence of youth now occupies the same space in which brutal violence was committed during the war inspired McQueen to search for how past and present are intertwined, in space as well as time.

Echoes from the past

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, McQueen started filming life in around a hundred locations in Amsterdam. Three years later he had collected 36 hours of raw material. From this, he edited his 4.5-hour documentary Occupied City, which was given a special screening at the Cannes Film Festival in May.

The film’s audio tells us what happened in all of those locations during Amsterdam’s occupation between 1940 and 1945. The texts have been written by Stigter and largely come directly from her Atlas, although McQueen emphatically wanted to meander through the city without a fixed route. This way the viewer can get lost in their own feelings, thoughts, and associations. At the same time, the film is about how relevant that past is in the present.

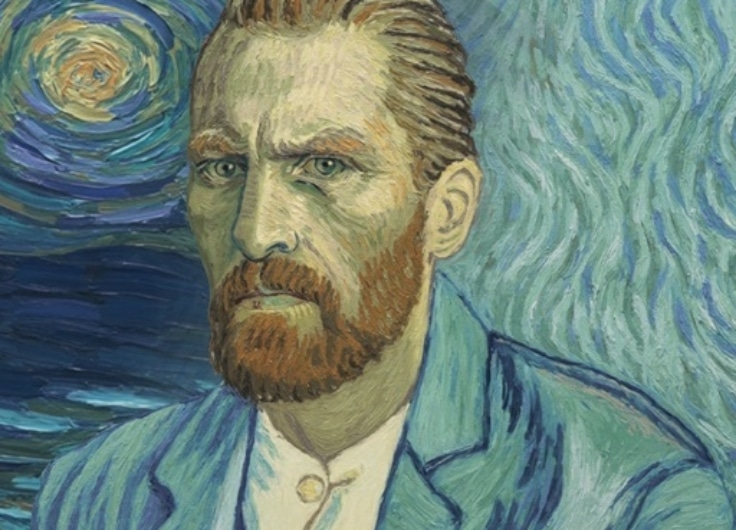

Screenshot 'Occupied City'

Screenshot 'Occupied City'Since McQueen started filming, many things have happened in the world that echo this occupied past in its violence and resistance: COVID-19 measures, the storming of the Capitol, the murder of George Floyd, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the effects of global warming.

McQueen alternates random street observations – someone falling off their bike or children sledding, for example – with official events like Remembrance Day on Dam Square, or the opening of the Holocaust memorial on Weesperstraat. Political demonstrations against climate policy, colonial oppression and racism also feature in the film, alongside watching fun on frozen canals, or the wedding of two women.

We see a fire brigade putting out a bin fire on New Year’s Eve, on a square that was renamed under the German occupation; a boy playing games with a VR mask, in a house where another boy escaped to the neighbours during a raid; a woman sticking a cotton swab up her nose at a COVID-19 test site, which was once the office of a paramilitary Nazi organisation with several tens of thousands of Dutch members. Teenagers smoke cannabis in a park where people were once shot in reprisal for the murder of a Nazi soldier. On Museumplein, where the Germans organised military parades eighty years ago, police disperse demonstrators protesting against COVID-19 regulations with water cannons. On the Max Euweplein, where a pregnant political prisoner once was kicked so badly that she suffered a miscarriage, chess is being played in the sunshine. In the Vondelpark, where the Germans organised midwinter festivals to promote Germanic culture, people of colour sat chilling in the grass.

There are a seemingly endless number of places in Amsterdam in which all kinds of things took place under the German occupation. The contrast with today’s free and liberal Amsterdam is considerable. It owes its contemporary face to the battle that took place during that time. Yet at the same time, we can feel that that freedom is under pressure once more, and has to be repeatedly fought for – especially in times of major political issues, intolerance and polarisation, when privacy loses ground to surveillance and security, and in which the government is increasingly pitted against its citizens.

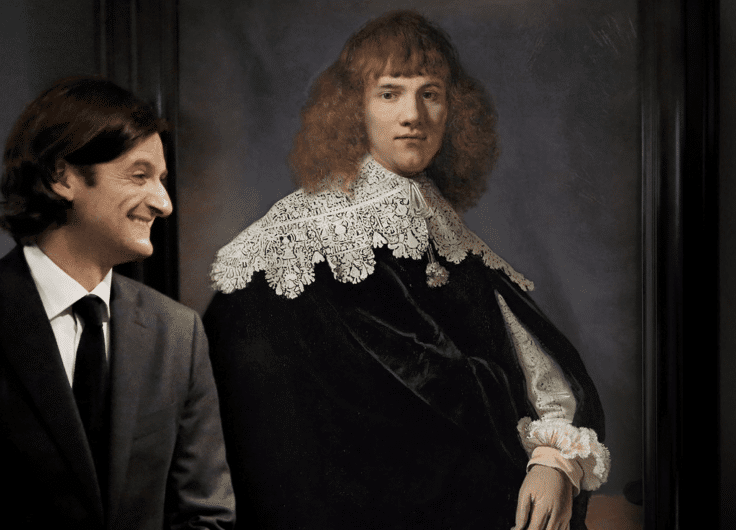

Screenshot 'Occupied City'

Screenshot 'Occupied City'McQueen has filmed in the streets and in buildings, from the waterways and in towers, and in a tram through foggy Amsterdam. He has filmed on squares, under viaducts, during the day and in the evening. At points, the narrative voice is silent and poetic piano music plays. Sometimes the images are absurd, like the shot featuring a number of large teddy bears sitting on chairs in an empty hotel lobby, with signs like “We are here for your safety.” Sometimes the viewer wonders whether uniformity is fascistic too, encompassed for example, in a sequence where a group of elderly people in a retirement home are wearing face masks, and are being instructed to do synchronised exercise. In another, more abstract shot, we see contemporary dancers dancing backwards – an act of anarchy perhaps?

Flow of images

McQueen wants to offer the viewer the space to reflect on what they hear and see. Occasionally he provides some subtle ironic commentary, for example, Bowie’s ‘Golden Years’ accompanies images of elderly people with walking frames getting their COVID-19 jabs. Towards the end of the film, the camera floats like a ghost through a ghost town, and the image of police cars and a few youngsters on bikes passing by after curfew hours, begins to slowly turn upside down.

Occupied City is a reflective documentary about contemporary issues like freedom, oppression and protest. Because of this, it forms a link between McQueen’s video installations and his feature films. Films like Deadpan, Bear and Static are driven by time, space and movement, while 12 Years a Slave, Shame, Hunger and other films are inspired by themes of resistance and deviation from the norm.

The flow of images and the bombardment of audio information in this amazing city portrait lead the viewer into a meditative state – precisely because it isn’t possible to catch everything in it. Sometimes you tune into the history and at other times you focus more on the images. This way you experience how past and present are also connected through the act of remembering and forgetting. What the viewer decides to focus on is personal. Big questions are posed implicitly, questions about what people live or die for.

McQueen has said in interviews that he didn’t want to make a history lesson, but rather a journey in which he makes the ghosts of the past visible now, with a view to the future. After a screening at the New York Film Festival, he said: “It’s not just about knowing who you are in the present, it’s also about not having to know, because there’s space for that. Because that space has been fought over in the past.”