‘Een bepaalde dag in het leven van iedereen’ by Stijn Vranken: Cheerful World History

Do you remember what you were doing on 14 February 1990? Not very likely. But author and screenwriter Stijn Vranken does remember, and it makes for an entertaining debut.

Valentine’s Day, 1990, was not a day like all the others. Or at least not in the life of Stijn Vranken, who shares a name and is not to be confused with the poetry performer and former city poet of Antwerp. This Stijn makes tv-programmes for the Belgian production company Woestijnvis, so clearly, he knows everything about that particular day. Or so he would have us believe.

Stijn Vranken

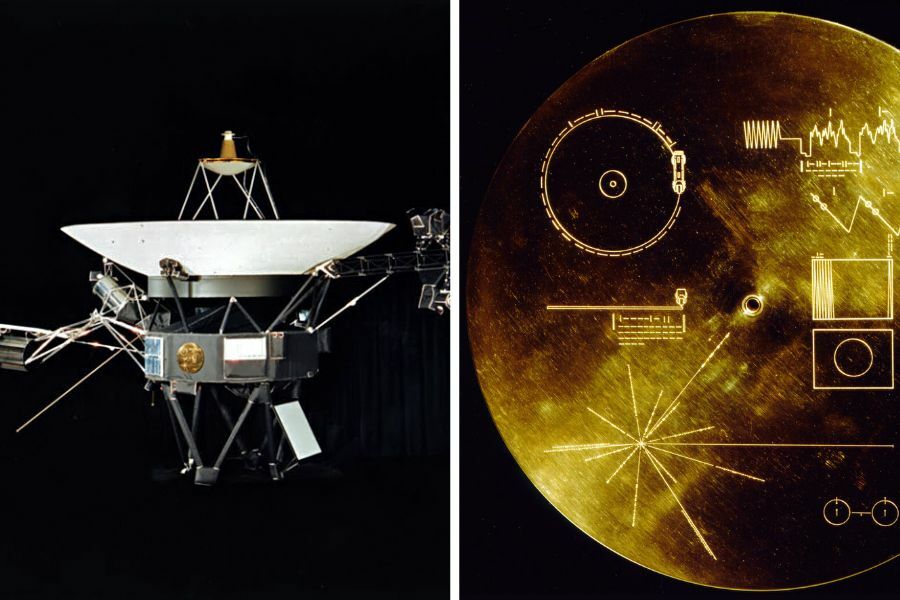

Stijn VrankenThis somewhat nerdy Vranken starts his novel with a short prologue about the Voyager, the unmanned space probe with a golden phonograph record on board, which reached the edge of our solar system on 14 February 1990. That record is a kind of gimmick by astronomer Carl Sagan – it contains messages for other living beings outside our solar system, should they ever meet Voyager, and happen to have a turntable handy. Like a mixtape, yes, but destined for a stranger, instead of a loved one.

14 February 1990 is also the day Voyager 1 sends a beautiful image of Earth back to base camp, the one that will make history: a Pale Blue Dot.

The unmanned space probe, Voyager, with a golden phonograph record on board.

The unmanned space probe, Voyager, with a golden phonograph record on board.© NASA/JPL

A snapshot of Earth on that particular day, that’s also how you could describe this debut. And there is another mixtape that plays an important part in the life of the young Vranken. Because since it is 14 February, not only astronomy but also love is in the air. At the very end of the book, Vranken recounts how a younger version of himself, armed with a homemade cassette of music and romantic messages, tries to get into the boarding school run by nuns where his sweetheart is confined.

He describes his break-in attempt with humour and flair, as a reader you start to root for this cunning and lovesick teenager, and you hope that as a reward for so much courage and inventiveness, he gets to kiss his sweetheart at the end of the day. Whether that happens, of course, our lips are sealed.

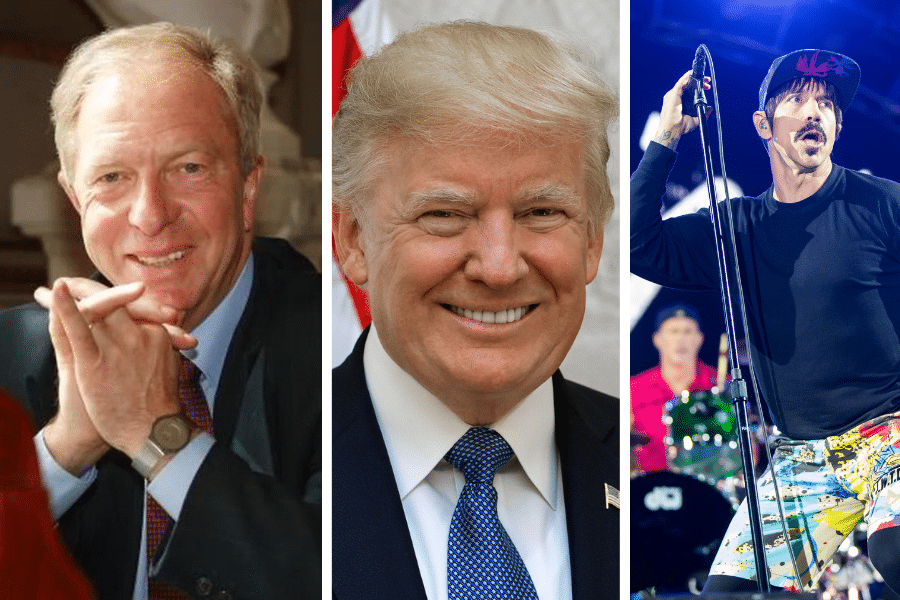

Before that grand finale gets going, we dip into the lives of several others on this particular day: A cabinet employee of former environment minister Theo Kelchtermans, who tries to attract the attention of an old lover; an employee of the French water brand Perrier who is falsely accused of negligence; real estate mogul Donald Trump; lead singer Anthony Kiedis of the Red Hot Chili Peppers and a few more, from rich people in India and a fortune teller in Tonga to revolutionaries in Colombia and bickering polar explorers in Antarctica.

Former environment minister Theo Kelchtermans, real estate mogul Donald Trump and singer Anthony Kiedis

Former environment minister Theo Kelchtermans, real estate mogul Donald Trump and singer Anthony Kiedis© rr / Shealagh Craighead / Sven Mandel

Vranken describes their 14 (and 15) February 1990 in separate chapters, yet one way or another, all the stories are intertwined. Certain themes recur, such as the benzene-contaminated bottles of Perrier that must be removed from shelves all over the world. It is like that story of a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil and months later causing a tornado in Texas. Seemingly insignificant incidents and encounters thus majorly affect the lives not only of the main protagonists, but also of those in other chapters. How the stories are woven together is often cleverly done, though somewhat predictable at times.

Vranken neatly stitched together events from the lives of a dozen people, and turned it into a more than entertaining book

The writing is full of movement and sparkle, with bursts of storytelling pleasure. Een bepaalde dag in het leven van iedereen (One Day in Everyone’s Life) is peppered with humour that is at times reminiscent of author Herman Brusselmans, but without his bawdiness. Sometimes you can spot a funny sentence or comment a mile off, but the fact that Vranken still gamely finishes the joke often reinforces its comedic effect.

The fact that it can either hit or miss the mark is almost inevitable in a book of this size, and of course, it also has to do with personal taste. Some readers will find this fantastic, but others may get bored.

You should not turn to Vranken for philosophical depth or grand thoughts, apart from a one-off and somewhat clichéd reflection about Valentine. But Vranken has no pretensions either, he has no message to convey. Though he has bent world history to his will, neatly stitched together events from the lives of a dozen people, and turned it into a more than entertaining book.

What is or isn’t true hardly matters. It is no coincidence that one of the main characters in this book coined the term “alternative facts”, even though he was already president of the US at the time, and no longer just the crass and self-important real estate magnate he is here.

Excerpt of ‘Een bepaalde dag in het leven van iedereen’, as translated by Elisabeth Salverda

14 FEBRUARY 1990

the cabinet employee

The cabinet employee is sweating. He seems more nervous than the minister. Because today is the crucial day. The press conference is scheduled for two o’clock. Not too late, so the tv-reporters can still get their report in for the news at seven, or half past, depending on the channel. But also not too early, so that even the least motivated newspaper journalists still have time to lie in, drink a few coffees, perhaps write something, have a bite to eat and take the train to Brussels, or the car. Two o’clock is a great time for a press conference. Everyone in the cabinet of the Environment, Nature Conservation and Land Development agreed. Forty-two minutes to go.

The table is ready. Someone has decided to drape a long, white tablecloth over it, the edge almost down to the carpet. White represents purity. Cleanliness. Although the reason someone chose a white tablecloth is probably more banal. Because white tablecloths are the only ones available, for example, in the not-very-inviting cabinet press room. The fabric shows faint circular traces of spilt coffee. An appropriate metaphor, the cabinet employee thinks, when he notices the stains. But he has the tablecloth replaced with a more pristine one just to be on the safe side. No one has ever escaped a reprimand from a minister with appropriate metaphors.

Behind the table are four chairs. Four. At first, there were only three. But the cabinet employee thought he had the right to at least also be in the picture. He really made a point of that. To the surprise of his colleagues, because he is usually not such a go-getter. But after all, he is the one who squeezed the lion’s share of the brand-new policy plan out of his Olivetti ET Personal 55. He has done most of the work by far. And so Johnny, the chief of cabinet, had given in. ‘Okay, I get it. Of course, you want to be in the picture, too, so that your wife can see with her own eyes that you have not worked late all those evenings for nothing. But would you please keep your mouth shut, okay? Let us do the talking.’

And so a fourth chair was added, on which the cabinet employee can sit in silence. Johnny will introduce the press conference. Then the minister will speak. Then Johnny will ask if there are any questions, and the minister will answer them. And if he does not know the exact answer, the minister will say something to conceal from the journalists present that he does not know the precise answer. The minister is very good at that. And so he must be, because even a minister cannot know everything. The policy plan that he will present today, for example, has almost a thousand pages of tables, calculations, descriptions, hypotheses, conclusions, intentions, and measures. But the minister will never say: ‘Oh dear, I don’t know, so for the answer to this question I would like to give the floor to my employee, because after all he is the one who did all these calculations over and over again; he knows those tables better than his own wife.’ And just as well. Because the cabinet employee would stutter and stumble over his own words. Everyone plays their part.

His part. He has been a cabinet employee for more than fifteen years now. Always on Environment or Urban Planning. In this way, he still became a do-gooder, although he had to wriggle into the categories ‘professional’, ‘hardworking’ and ‘punctual’. But what can you do? He was too smart to remain a hippie all his life. Too malleable. Too conformist. And so – it happened automatically, without planning – he suddenly had a steady job. That’s how it goes. At first, you are half a drop-out and you protest against The System with your heart and soul. You are a fervent defender of Freedom. And not much later you set your alarm to half past six, to make sure you don’t get reprimanded for arriving a minute late to work.

Stijn Vranken, Een bepaalde dag in het leven van iedereen (One day in everyone’s life), Pelckmans, 2022., 460 pages