‘Stones Have Laws’ Portrays Past and Present Traumas of the Maroon Community

Many documentaries look at other cultures from a Western perspective. But with Stones Have Laws (Dee Sitonu a Weti) – a documentary on the Maroons, descendants of people who escaped from slavery in Suriname – the Dutch artist- and filmmaker-duo Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren de Haan, in collaboration with Surinamese playwright Tolin Erwin Alexander, have made a film with the Maroons, rather than about them. This difference is crucial.

The prevailing image that enslaved people passively accepted the inhumanity of their situation is definitely not true of Suriname. Almost as soon as slavery was introduced in the early seventeenth century to this Dutch colony – around five times the size of the Netherlands – there was resistance to it from the African slaves. Most often, this resistance meant running away, which was facilitated by the fact that the plantations, mainly producing coffee and sugar, were situated on rivers. These offered a good escape route deep into the extensive jungle (90 per cent of Suriname consists of a tropical forest), where it was difficult for plantation owners and the colonial army to track down the fugitives.

Hidden deep in the jungle the runaway former slaves – who in colonial times were known as bosnegers (bush negroes) or boscreolen (bush creoles), in our time the Maroons – established small self-sufficient communities. But the Maroons did not disappear altogether from colonial society. They regularly attacked plantations, set fire to them, killed the owners and freed the enslaved. These violent actions were so successful that in 1760 the colonial government was forced to conclude a peace treaty with them. The administration promised to leave the then around 4,000 Maroons alone if they stopped attacking plantations. For their part, the Maroons promised not to take in any new fugitives, but instead to hand them over to the government. However painful, the majority of Maroon communities went along with it.

A remarkable practice

The unique peace treaty – between a colonial ruler and runaway former slaves, only Jamaica had a comparable agreement – ensured calm. In the interior, the Maroons developed an autonomous culture, grafted on African traditions and characterised by a belief that humanity is part of nature, rather than in opposition to it. Everything in nature is animate, including the forest spirits who also make themselves heard.

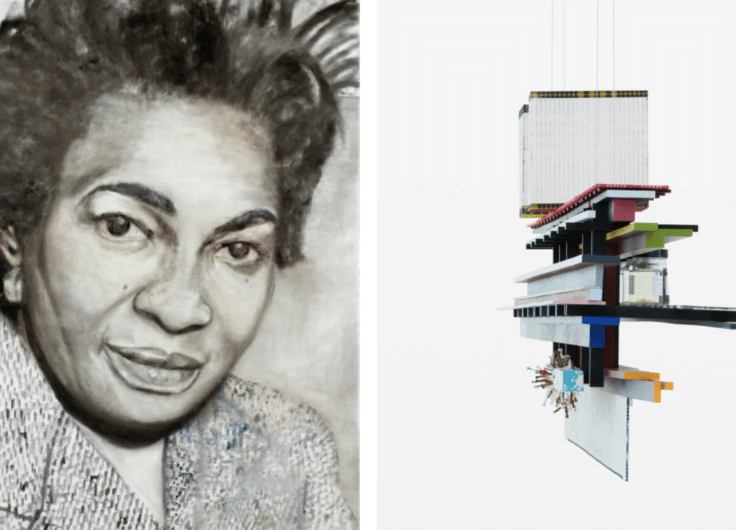

Still from Stones Have Laws

Still from Stones Have Laws© Van Brummelen & De Haan, VRIZA, SeriousFilm en Ideal Film

Like all indigenous cultures, the Maroon way of life is threatened by modernisation and globalisation. Many descendants of the Maroons, who now number 120,000 and make up almost a quarter of the Surinamese population, no longer live inland, but in villages or in the city of Paramaribo.

These descendants are not the subject of the documentary Stones Have Laws (Dee Sitonu a Weti) by Lonnie van Brummelen, Siebren de Haan and Tolin Erwin Alexander. Their film focuses on the Maroons in the interior, who offer their views on the colonial past and the modern threats to their way of life.

Stones Have Laws does not look at the Maroons through a western lens but starts from their perspective

Stones Have Laws does not look at the Maroons through a western lens but starts from their perspective. The film’s content has been determined by what the Maroons themselves want to tell and show. The filmmakers are open about this unique collaborative practice: a discussion between the Maroons about whether they will give these ‘white people’ permission to film them is shown. Can these whites be trusted? Does not experience show that whites always bring misfortune? Only when the Maroons are confident that the filmmakers do not seek to profit and that they will not have to sign away their rights, can they get to work.

Spiritual inspiration

Stones Have Laws is fascinating because of what the Maroons have to say about their past and present, but also because of what is left unsaid – more on that later.

The colonial era is extensively discussed, with mythical memories of the escape from slavery and the colonial peace treaty of 1760. More recently, in the 1960s, the traumatic reminder of the construction of the Brokopondo reservoir in the Surinamese interior for the supply of electricity, in which an area the size of the Dutch province of Utrecht was flooded and dozens of Maroon villages were sunk.

Like all indigenous cultures, the Maroon way of life is threatened by modernisation and globalisation

One Maroon expresses this environmental disaster in spiritual language: ‘The spirits told us that they had seen a vast sea where the water rose higher every day despite there being no rain.’ The plea to the gods to stop the rising water went unanswered, so the Maroons fled the area on boats. In the water the fish ‘seemed drunk’, rabbits and turtles drowned and ‘all holy things’ in the villages were destroyed.

Still from Stones Have Laws

Still from Stones Have Laws© Van Brummelen & De Haan, VRIZA, SeriousFilm en Ideal Film

The language of money

A more recent threat to the Maroon way of living is gold mining in the Surinamese interior. Gold fever is increasing, the mining by multinationals and the illegal activities of private entities leading to destruction of the jungle. Centuries-old trees are mercilessly cut down, which is sacrilege in the eyes of the Maroons because ‘the voices of the gods’ reside there.

For Maroons, not only people, but every living organism has the right to protection by law. Trees and even lifeless things such as stones have the right to protection and respect. Bitterly, a Maroon observes that Maroons used to make fun of those digging for gold, but that now some of them also take part in gold mining. They have to, because ‘we are no longer allowed to hunt, since the forests are now owned by the whites.’

Still from Stones Have Laws

Still from Stones Have Laws© Van Brummelen & De Haan, VRIZA, SeriousFilm en Ideal Film

Not only is the jungle ecosystem destroyed by tree felling, but the frequent use of mercury in gold mining leads to heavy contamination of groundwater. The Maroons do not die from it, but it makes them sick, one of them remarks sadly. Their ancestors found a hiding place in the forest, but now the sounds of ‘the land of money’ can be heard there. The conclusion is bleak: ‘Our experience with whites is that if they plan something they will go ahead, even if it costs lives.’

An unstable balance

Stones Have Laws theatrically awakens – through its many scenes that are staged – the traumatic colonial memories of the Maroons and the new neo-colonial threats to their way of life. The images of the jungle, accompanied by the tremendous natural sounds of wind, clattering rain and flowing rivers, and the incessant chirping of crickets, render the natural and spiritual world of the Maroons intensely tangible.

The filmmakers do not make the mistake of presenting the traditional lifestyle of the Maroons as static

Depicting the Maroon way of life, the film’s languid pace and almost hypnotic imagery also take the viewers in. We are immersed in a culture in which people are not separate from but part of nature. To show this, Van Brummelen, De Haan and Alexander eschew the fly-on-the-wall approach that dominates the world of documentaries – a method that suggests no filmmakers are involved with the film –, opting instead for a combination of documentary and fictional elements.

The monologues and dialogues of the Maroons have been scripted by the filmmakers and the Maroon community, but the images of their natural environment are documentary. Also, the filmmakers do not make the mistake of presenting the traditional lifestyle of the Maroons as static. The film shows that the Maroons are not averse to using modern inventions, such as chainsaws, to help with felling a tree.

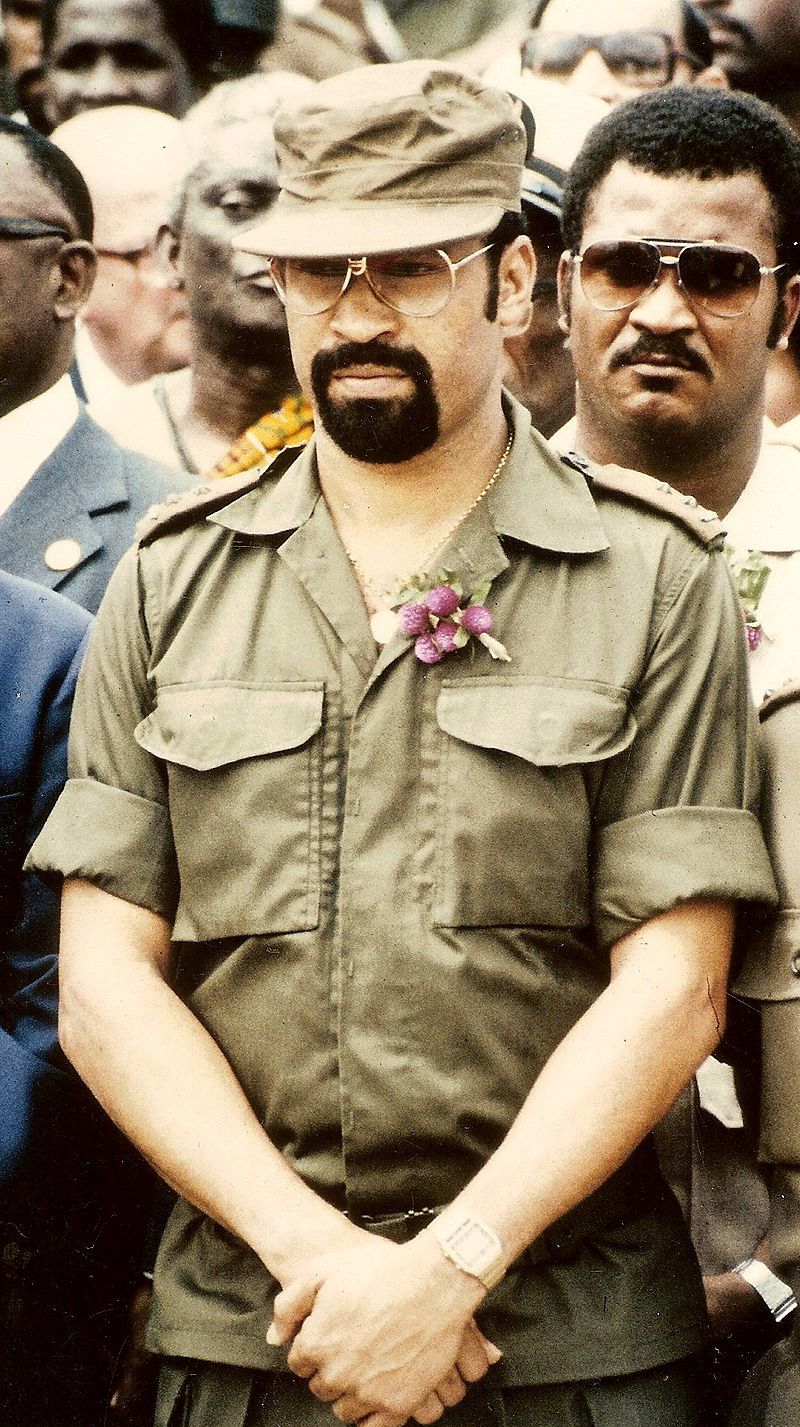

Dési Bouterse as military leader of Surinam in 1985.

Dési Bouterse as military leader of Surinam in 1985.© Wikimedia Commons

But something is missing: Suriname’s civil war between 1986 and 1992, which left deep wounds. The battle between military leader Dési Bouterse and his former bodyguard Ronnie Brunswijk, of Maroon descent, led to ruthless attacks on both sides, with the Maroons being hit hard. A gruesome low was the 1986 mass murder of at least 39 innocent civilians – men, women and children – in the Maroon village of Moiwana by Bouterse’s troops. The perpetrators have never been punished.

Is this horrific event not included in Stones Have Laws (Dee Sitonu a Weti) because the wound is still too fresh? Is it impossible to talk about this trauma thirty years on, because the civil war still divides Suriname, where more than five ethnic groups live together in an unstable balance? By not mentioning the consequences of the civil war for the Maroons, Stones Have Laws unemphatically displays the fragility of Surinamese society at large.