Strange, the Flemish Use of the Word ‘Vreemd’

Call me a foreigner, a vreemdeling, but I find it strange how the Flemish media and government use the word vreemd, a word with connotations such as ‘foreign’, ‘deviant’, ‘unusual’.

A substantial proportion of Belgians believe ‘too many people of vreemd

origins live in Belgium’, I read recently in an opinion piece by the writer Tom Naegels. He was responding to the result of a survey showing that the vast majority of Belgians on two sides of the language border and at both ends of the political spectrum think people of “vreemd origins” should adapt to “European culture”.

Mistrust towards newcomers, people of “vreemd origins” is inevitable, was the claim in Naegels’ article; we have to learn to live with it. Mistrust strikes me as something you should combat rather than feed, to start with by avoiding categorising people who come from elsewhere as “vreemd”.

Belgians should integrate into European culture themselves

There’s actually a good chance I too would have answered yes to the question as to whether newcomers should adapt to European culture. But my first thought: those Belgians could start by integrating into European culture themselves. They should act in accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights, stop hounding migrants in transit as if they were cattle, just offer them bed, bath and bread, and not keep detainees in inhuman conditions. Then the European Court of Human Rights wouldn’t need to give Belgium yet another rap over the knuckles.

The Palace of the Nation in Brussels, home to both Chambers of the Federal Parliament of Belgium

The Palace of the Nation in Brussels, home to both Chambers of the Federal Parliament of BelgiumWhere's that from?

They should acknowledge that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. The man sitting next to me in Ostend’s hippodrome shouldn’t point at my daughter from Rwanda and foster son from Angola and ask, ‘Where’s that from?’ as if they were inanimate objects.

The government should finally tackle the biggest source of faulty integration: the Belgian education system that does so little to close the gap between newcomers and native Belgians. The Belgian politicians need to put into practice for once the talent for compromise they so often pat themselves on the back for, which in their view makes them the best of all Europeans.

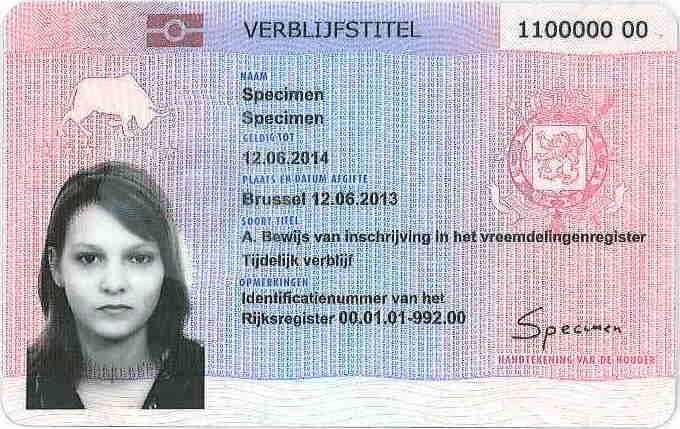

Vreemdeling card

Vreemdeling cardBut yes, I’m just a vreemdeling myself. When I came to live in Flanders more than three years ago, my status was immediately made clear to me. As a Dutch national I was given a “vreemdeling card”.

I myself am a vreemdeling who differs only minimally from “normal people”. But even for me, integrating into this country seems surprisingly awkward. How terribly difficult it must be, then, for people who come from further away and don’t have white skin?

On one point Naegels is completely right: whether newcomers ‘are perceived in daily contact as vreemd or “well integrated” remains subjective’.

I was born in Ostend and up until the age of eighteen, when I became Dutch, I held a Belgian passport. I have now lived back in my country of origin for several years. I cheer when Thomas De Gendt wins a tour stage. The painters who stir my heart are Léon Spilliaert and Gustaaf De Smet. I consider Lieven Tavernier and Jonas Winterland superb entertainers.

In my view the most important authors of the Low Countries – Louis Paul Boon and Hugo Claus – are writers of Flemish origins. I’d choose paling in ’t groen as my last meal. But to the Flemish, due to my accent, I will always be the Dutchman, and if I express an anomalous opinion then I’m the Dutchman with the big mouth.

The Belgium of dreams

There was once a Belgian historian, Henri Pirenne (1862-1935), who characterised “Belgian civilisation” as “international in its terrain”. He said its strength lay in the fusion of ideas from all over the place at a European crossroads, in being open to views of all kinds and in taking what was good from all sides.

The Belgians should integrate into that Belgium they dream of and shake off their obsession with background and fear of what is vreemd. For a start they should stop labelling everything that comes from elsewhere as vreemd.