Mussels, Magritte and Maeterlinck: The Universal “Belgitude” of Stromae

That Jacques Brel has been an inspiration to him is well-known, but Stromae also has connections to other phenomena and figures from the Belgian collective imagination: from fries and mussels to Maurice Maeterlinck and René Magritte. Stromae expresses and depicts the diversity of Belgian society through the collision of his Belgian-ness and Brussels patriotism with a multitude of diverse perspectives.

“C’est un héros!” (She’s a hero), he sings, eyes closed, head slightly bowed, his hands resting on a lectern. “Et ce sera toujours fièrement que j’en parlerai” (and I will always speak of her with pride). In the video clip for ‘Fils de joie‘ (Son of Pleasure), one of the singles from his third and most recent album Multitude (2022), the Belgian artist Stromae (the pseudonym of Paul Van Haver and anagram of maestro), dressed in a military uniform and sporting an elaborate hairstyle, speaks in the shadow of a huge triumphal arch. The camera zooms in on the tightly choreographed movements of limousines and dancing soldiers. The ceremony is entirely dedicated to the memory of a deceased sex worker – also a mother – as one of the characters incarnated by Stromae in the video proves when he sings: “J’suis un fils de pute, comme ils disent” (As they say, I am the son of a prostitute.)

It is not immediately clear where the memorial ceremony is taking place. Pastel-coloured flags that don’t belong to any existing country flutter in the breeze, dancers wear costumes that are vaguely reminiscent of military uniforms from certain regions, but there’s nothing identifiable. According to the bilingual description that precedes the video, we are in un pays imaginaire

(a made-up country). Stromae and his team did this intentionally, so viewers would not know where the clip took place. The dancers’ uniforms were modelled on those of Asian, African, Latin American and European regiments, and the team drew inspiration for the choreography from both the iconic Irish dance performance Riverdance and a TikTok video of grieving coffin bearers dancing during a funeral procession in Ghana.

‘Fils de joie’ (Son of Pleasure) also shifts between various musical styles and regions: a baroque harpsichord overlays Brazilian baile funk, and a sample from the Netflix costume drama Bridgerton is draped over that mix – a mix found in every song on the album, making the sound seem to come from everywhere and nowhere: “L’idée, c’était d’à chaque fois brouiller les pistes” (The idea was to obscure our tracks – hide the location.) In interviews, Stromae explained that his intention was to show that the future of pop music can be found in world music. When he wrote the new songs, he listened to music from all corners of the world. All of those influences – from a Chinese string instrument like the erhu; to Andean charango

guitars, to a Turkish flute like the ney – can be heard on the album, but in such a way that the result feels more like a true reflection of a global music culture than a casual series of touristic day trips.

Stromae's musical projects are both globally oriented and firmly anchored in Belgian soil

Although the Belgian daily De Standaard referred to Stromae’s “un-Belgian star appeal” after his performance at Werchter Boutique in the summer of 2022, ‘Fils de joie’ shows that his musical projects are both globally oriented and firmly anchored in Belgian soil. Or, as he said about Multitude

himself in an interview in The New York Times: “It’s my vision of world music emanating from my hometown, Brussels.” This also applies to the video of ‘Fils de joie’ (Son of Pleasure), which, despite projecting a disorienting potpourri of international references, also offers a local anchor point. After all, the prominently depicted triumphal arch strongly resembles that of the Cinquantenaire Park in Brussels. The first version of this arch (made of wood) was erected in 1880 to commemorate Belgium’s fiftieth anniversary. In 1905 it was replaced by the current structure, which was designed to serve as a gateway to the Tervurenlaan, a new avenue connecting Brussels with the Congo Museum ten kilometres away. All this was personally financed by the then monarch Leopold II, to the greater honour and glory of the fatherland – but especially to celebrate his colonial exploits in the Congo Free State.

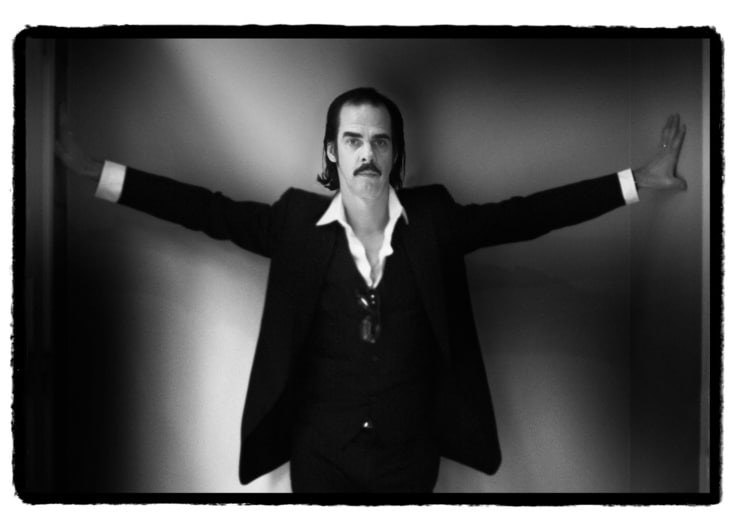

Stromae at Werchter Boutique in the summer of 2022

Stromae at Werchter Boutique in the summer of 2022© Joost van Hoey

The monument originally functioned as the architectural focal point of a national culture of remembrance funded by colonial conquests. But in Stromae’s music video it appears in a completely different light. In the clip, the singer takes on the voice of various characters – a customer, a pimp, a police officer and a son – each of whom gives his unvarnished opinion about the deceased sex worker. Interestingly, she, herself, does not get a voice. She does, however, get her own monument, which radically changes a colonial archetype so that it becomes a memorial to a maligned woman.

Or, rather, maligned women. Because the honour is not bestowed upon a single individual. Although only one shiny coffin has a central role in the ceremony, several people in the video hold up portraits of different women. In this way, world star Stromae gives universal resonance to the memory of the deceased sex worker. All the sex workers in the world are commemorated by a crowd of listeners that spans the globe. And because ‘Fils de joie’ (Son of Pleasure) is so danceable – and Stromae’s interpretation of himself as a proud fils de pute (son of a prostitute) for the duration of the song is so memorable – the many filles de joie

(women of pleasure) in Belgium and elsewhere will become etched on our memories and not soon forgotten.

Brussels, Belgium and the world

In the collected arts of music, video and fashion within which Stromae works collaboratively with his wife, Coralie Barbier, and his brother, Luc Van Haver, Belgium does not appear merely as a made-up country. Despite a loaded past and numerous fault lines in the present, it is a real place that stimulates the imagination in a positive and unifying way. This is remarkable because collective memory in Belgium has long been marked by conflict and questions. What does Belgium stand for? How should the history of the country and its communities be remembered? What does its future look like? And who will determine what that future will be?

Instead of flirting with postmodern clichés about a bland, Belgian non-identity, Stromae assertively shows how a caring collective imagination full of multiplicity and contrast can take shape in a changing world. Brussels and Belgium both serve as artistic springboards for him.

The local character of Stromae’s musical projects is immediately apparent from the opening track of his strongly 1990’s house-influenced debut album Cheese (2010), which gained attention mainly due to the worldwide success of the single ‘Alors on danse’ (So We Dance). In the pumping, Europop song ‘Bienvenue chez moi’ (Welcome to My Home), Stromae invites the listener into his Brussels recording studio. The scraps of paper on the floor are like autumn leaves. On the walls yellow sticky notes on the red wall suggest the Belgian tricolour that, early in the video, is carried across the scene:

Bienvenue chez moi

Ces quatre murs en plastique

Sont pleins de papier, de tas de Bic

Des tas de feuilles à moitié mortes

À moitié bourgeons, à moitié fortes

Un jour vertes, un jour brunes

Noires, jaunes, rouges et un jour plumes

(Welcome to my home

These four plastic walls

Are full of paper and piles of ballpoint pens

A pile of paper leaves, half-dead

Half-rich, half-strong

One day green, one day brown

Black, yellow, red and, one day, feathers)

The Belgian flag flies even more explicitly in the video for Stromae’s ‘Ta Fête’, one of the singles from his acclaimed second album Racine Carrée (2013). In the clip, he expresses his ambition to make this song the national hymn, “non pas l’hymne national de la Belgique, mais l’hymne des Diables Rouges à la Coupe au Brésil” (not the national anthem of Belgium, but the anthem of the Red Devils football team at the Brazilian Cup). In one version of the clip for this song, ‘Leçon 28 Ta fête’, which playfully explains the concept of another version of the video for the song, he camps in a tent on an abandoned football field – complete with a drying line hung with socks in the colours of the Belgian flag and a synthesizer decorated with action figures of footballers Eden Hazard and Nacer Chadli – and hilariously accosts various Red Devils’ players – even in the toilets – to pitch the idea of ‘Ta fête’ as a team anthem. By means of this kind of absurdist self-relativization, Stromae explicitly positions himself as a Belgian artist, and he does it when the national team is competing in an international event – one of the rare times that a kind of sports enthusiasm fills Belgian TV screens and supporters’ stands. It’s a collective emotion that shows – if only for a moment – traits of national sentiment.

His humour and patriotic references place Stromae firmly in the tradition of "belgitude"

The humour of this clip and its patriotic references place Stromae firmly in the tradition of “belgitude” as it was expressed in the second half of the last century by artists such as Marcel Broodthaers. At the same time, his playful self-presentation is in keeping with a twenty-first century “new belgitude”, an idea often associated with the way prominent Belgians from migrant backgrounds – such as footballer Vincent Kompany – uncomplicatedly claim an inherently diverse Belgian identity. In 2013 Stromae, like Kompany, was hailed in the opinion pages as a champion of this multilingual and diverse new belgitude when he addressed the audience during a concert on the occasion of the Festival of the French-speaking Community, saying: “Everything okay? Do you speak Flemish? Do you speak Flemish?! In Brussels we speak French and Flemish, okay?”

It might be quite a stretch to present Stromae as a Belgianist – or, who knows, even as a French-speaker in tune with the cultural attitudes of a Flemish nationalist flamingant – on the basis of such statements. After all, Stromae’s live performances exude a Belgian flavour that tastes more of playfulness than linguistic politics. His backing band and the crowds in the video for ‘Ta Fête’ are dressed in bourgeois suits and bowler hats that seem to have been plucked straight from the wardrobe of the Brussels surrealist René Magritte. Stromae regularly uses classic works that represented the discourse of the Belgian-patriotic underdog. This is evident from, among other things, the concert video of Racine Carrée‘s world tour, recorded during a sold-out performance in Montreal. There, Stromae introduces the song ‘Moules Frites’ – which links the image of Burgundian Belgium to the AIDS problem through sexual imagery – by fulminating that the French have improperly claimed the invention of ‘French’ fries:

Arrêtez de mentir à la terre entière s’il vous plaît! Parce que moi je viens de Belgique. Enfin, à moitié; évidemment tous les belges ne sont pas basanés. Et en Belgique on connaît la véritable histoire des frites. Non, on dit pas des French fries, monsieur. On dit des BELGIAN FRIES! Vous avez déjà eu beaucoup de choses, les français, laissez-nous quelques petits trucs quand-même.

(Please stop lying to the whole world! Because I am Belgian. Well, halfway; obviously, not all Belgians are swarthy. And in Belgium we know the real story of fries. No, sir, we don’t say French fries. We say BELGIAN FRIES! You have already claimed a lot of things, you French; leave a few small things for us!)

In one stroke, Stromae attaches the explicitly Belgian character of his work to his mixed roots – his mother is Flemish, his father Rwandan – in front of an international audience of Canadian concertgoers. This playful national framing also proves important during performances on Belgian soil: for example, when standing in front of a predominantly Dutch-speaking audience the pop star has for many years interspersed his narrations with the phrase: “Thank you, my countrymen!”

Not only Belgium, but also Brussels – the city where Stromae was born and still lives – takes a central role in how he presents himself to his audience

Not only Belgium, but also Brussels – the city where Stromae was born and still lives – takes a central role in how he presents himself to his audience. In interviews for an English-speaking audience, he likes to talk about how he grew up in the Laken district of Bockstael among friends of Turkish, Moroccan, Congolese and Rwandan descent. And when asked about his favourite city, he resolutely chooses Brussels, but with the climate of Los Angeles, because “Brussels is one of the best cities on the planet, but the weather is a nightmare”. The Brussels weather plays a prominent role in the video clip of the monster hit ‘Formidable’, in which Stromae hangs around the famous Avenue Louise roundabout during a rain-soaked morning rush hour – the image serves to visually anchor the video in the Brussels public space that is explicitly mentioned at the start of the video: 8:30, 21 May 2013, Bruxelles, near the roundabout at Avenue Louise.

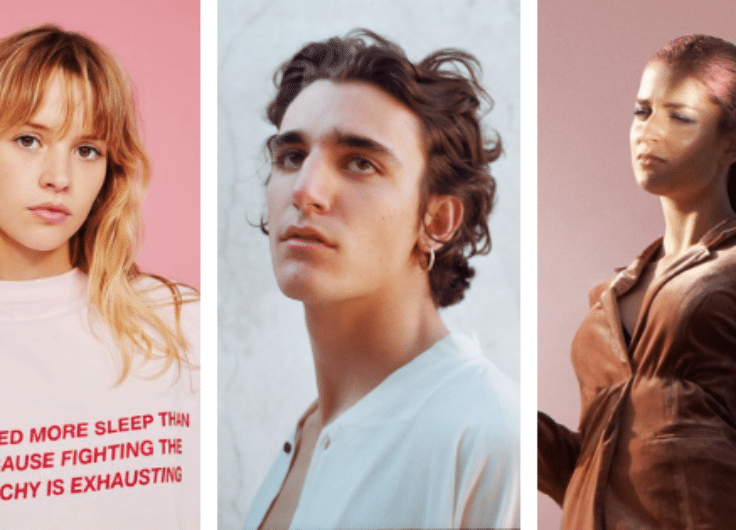

This focus on the Belgian capital also manifested itself when Stromae put his musical career on hold due to health problems and concentrated on other activities of his creative label Mosaert (an anagram of Stromae), which launched a fashion project and has produced videos for international artists such as Dua Lipa and Billie Eilish. Although the first capsules – as Mosaert’s clothing lines are called – were inspired by African prints in waxblock or wax hollandais, the fifth capsule was loosely inspired by Art Deco and Art Nouveau motifs, described on Mosaert’s website as “two artistic movements that have shaped our capital, Brussels”. Or as Stromae’s sparring partner, stylist and wife Coralie Barbier puts it in an interview with L’Echo: “Avec l’Art déco et l’Art nouveau, nous sommes revenus chez nous” (By using art deco and art nouveau, we have come home.)

From Maeterlinck to the maestro

Stromae’s open Belgian-ness and Brussels urban patriotism have clearly not stood in the way of his success with regard to French-speakers and francophiles. On the contrary. In 2016, for example, he was awarded the grande médaille of the Académie Française because, as “le seul chanteur de sa génération qui soit mondialment connu” (the only singer of his generation who is known worldwide), he has succeeded in getting French-speaking youth to listen to music in their mother tongue. In recent years, successful Brussels artists such as Angèle and Damso have perpetuated this trend.

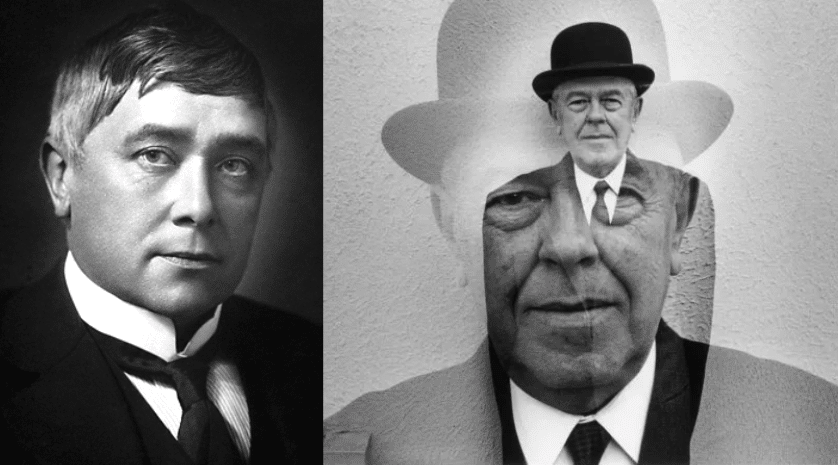

Maurice Maeterlinck and René Magritte

Maurice Maeterlinck and René Magritte© Wikipedia

But more so than his younger Brussels-based musical colleagues, Stromae seems to spontaneously tap into a tradition of national hybridity that has determined the image of Belgium abroad since the nineteenth century. To distinguish themselves from the French, intellectuals in the young nation-state founded their vision of “the Belgian soul” in a racially defined bicultural identity. This was determined by the combination of the French language with what they saw as Flemish peculiarities rooted in Breugel Fairs and Medieval source texts. Francophone Flemish authors such as Emile Verhaeren and Maurice Maeterlinck, hailed respectively as Belgium’s national bard and the first (and only) Belgian winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, exported the image of a bicultural Belgium abroad through a school of Symbolist texts that were full of masks and mirror images, allegories and doppelgängers. Due to the success of their “typically” Belgian Symbolist writing, both authors were soon lauded as stars of fin de siècle world literature.

Although world star Stromae avoids racial thinking a century later, he also injects a good dose of Belgian contrast into his musical oeuvre. This was already apparent from his debut album, Cheese, in which the party music and Stromae’s photographed toothpaste smile on the album cover – say cheese! – are in stark contrast to the troubled inner world of the characters he plays in the various songs. The second album, Racine Carrée, continues along the same lines. In the extremely danceable ‘Papaoutai’ Stromae, whose own father died in the Rwandan genocide, sings about fatherless sons. In the video, a boy dressed in a Stromae uniform lives with a plastic daddy who has the look — and frozen smile — of the pop star. While other children in the neighbourhood can romp with active fathers, this boy has to make do with an immobile role model. As a result, he, too, eventually becomes petrified, a doppelgänger of his absent father. Stromae juxtaposes key elements from the Belgian Symbolist tradition onto the super-diverse Belgium of the twenty-first century and makes traumatic world histories palpable through personal family stories and memorable verses such as: “Tout le monde sait comment faire des bébés, mais personne sait comment faire des papas” (Everyone knows how to make babies, but nobody knows how to make fathers).

Like Jacques Brel – that other French-speaking star of Belgian music – Stromae likes to role-play in his songs

Like Jacques Brel – that other French-speaking star of Belgian music – Stromae likes to role-play in his songs. He does this, for example, in ‘Tous les mêmes’ (All the Same), which zooms in on a relationship crisis in which a man and a woman stereotype each other’s point of view by speaking about each other in gender generalities: “Vous les hommes, ‘s êtes tous les mêmes / Macho mais cheap, bande de mauviettes infidèles”

versus “Rendezvous, rendezvous, rendezvous au prochain règlement / Rendezvous, rendezvous, rendezvous sûrement aux prochaines règles.” (“You men, ‘s all the same / Macho but cheap, bunch of cheating wimps” versus “Date, date, follow the rule / Meet, meet, follow the next rule.”)

In the video clip (and also live), Stromae visualises this stereotyping by playing a man with the left half of his body and a woman with the right half in scenes that are lit in pink and green respectively. The last shot initially represents the male and female perspectives in the same colours as two separate blocks. But that distinction crumbles when the camera zooms out to reveal an abstract mosaic in various shades of green and pink.

Unlike his artistic predecessors such as Maeterlinck and Verhaeren, the hybrid roots that Stromae sings about in twenty-first-century Belgium are therefore not bicultural. They do not presuppose a juxtaposition of the Flemish identity and the French language – or of the male and female perspective. Rather, the pop star depicts racines carrées or square roots: partial identities that multiply and unfold in a kaleidoscopic constellation of interconnected individuals. This is how it sounds for example in ‘Batârd’ (Bastard):

T’es d’droite ou t’es d’gauche ? T’es beauf ou bobo d’Paris ?

Sois t’es l’un ou soit t’es l’autre, t’es un homme ou bien tu péris

Cultrice ou patéticienne, féministe ou la ferme

Sois t’es macho, soit homo, mais t’es phobe ou sexuel

Mécréant ou terroriste, t’es veuch’ ou bien t’es barbu

Conspirationniste, Illuminati, mythomaniste ou vendu ?

Rien du tout, ou tout tout de suite, du tout au tout, indécis

Han, tu changes d’avis imbécile ? Mais t’es Hutu ou Tutsi ?

Flamand ou Wallon ? Bras ballants ou bras longs ?

Finalement t’es raciste, mais t’es blanc ou bien t’es marron, hein ?

Ni l’un, ni l’autre

Bâtard, tu es

Tu l’étais, et tu le restes!

(Are you on the right or are you on the left?

Are you a butch or a bourgeois-bohemian from Paris?

You’re either one or the other, you’re a man or you perish

Culture-vulture or prostitute, feminist or shut up

You might be macho, or homo, but you’re phobic or sexual

Unbeliever or terrorist, you’re widowed or bearded

Conspiracist, Illuminati, mythomaniac or sold out?

Nothing at all, or everything immediately, not at all, undecided

You changed your foolish mind? But are you Hutu or Tutsi?

Flemish or Walloon? Dangling arms or long arms?

Finally, you’re racist, but you’re white or you’re brown, right?

Neither.

Bastard, that’s what you are

You were, and you always will be!)

While “Flemish” and “Walloon” elements play a prominent role in Maeterlinck and Verhaeren, in Stromae’s stanza above they appear as supporting roles in a long list of many other identity-determining characteristics such as gender, class and political preference. Stromae is mainly concerned with demonstrating the absurdity of such identity lists. He therefore replaces the dual ethnic-cultural contrasts of Maeterlinck and Verhaeren with a cheerful fragmentation that doesn’t have a postmodern noncommittal appearance but, rather, has a radically multi-coloured appearance.

That Stromae radically rejects delineated boxes is most clear from the album Multitude, which he released in 2022 after a long radio silence. Contrast and mixing are ubiquitous. A song like ‘La solassitude’ (Loneliness) links with a neologism concerning the solitude that bachelors sometimes experience with the lassitude that couples can suffer from. The songs ‘Mauvaise journée’ (Bad Day) and ‘Bonne journée’ (Good Day) highlight the same day from opposite perspectives.

More strongly than on previous albums, the importance of caring for others comes first on Multitude: for example, he explores the (less) beautiful sides of parenthood in ‘Que du bonheur’ (Only Happiness) and in ‘Santé’ (Health) he focuses on the applause for essential professions such as cleaning staff and parcel deliverers, who were praised during the corona pandemic but also relentlessly overworked and underpaid. The importance of self-care is evident from ‘L’enfer’ (Hell), the second single from the album. In it, Stromae leaves the masks and characters behind for a while and takes a deep look into his own soul by talking candidly about the suicidal thoughts he struggled with after the Racine Carrée world tour. He sang that song for the first time on the French television broadcaster TF1, in the middle of a broadcast of the news that suddenly turned into a gripping surprise performance. In the preceding interview, Stromae discussed the links between the many musical influences of the songs to the album title: “On est tous multiple, on est plein de personnages différents, on a plein de personnalités différentes, on ne peut pas être résumé à un carcan, à une case.” (We are all multiple personalities, we are full of different characters, we have lots of different characters, we cannot be reduced to a straitjacket, to a box.) ‘L’enfer’ shows the dark side of that positive album title when Stromae sings about the crowd of lonely people he was unwittingly part of: “J’suis pas tout seul à être tout seul / Ça fait d’jà ça d’moins dans la tête / Et si j’comptais, combien on est / Beaucoup. (I’m not alone in being alone / At least that’s one less thing to worry about / And if I counted how many of us are lonely / Well, it’s a lot.)

Light and dark

Although his meteoric career in the music sector pushed him into the dark side for several years, it was also music as a shared experience – together with the support of his environment – that helped Stromae slowly climb back towards the light. This constant alternation between light and dark is therefore one of the key elements of his richly varied oeuvre. By actively exploring and sharing that confusing multitude of conflicting perspectives with listeners around the world, it seems that Stromae was able to become whole again.

Could the same process prove beneficial for a divided Belgium? With the necessary ingenuity, the divisions could be repaired. As Stromae’s music shows, Belgium, rich in contrast, can today serve as a source of inspiration, an artistic laboratory and an export product. Or as the pop star himself exclaimed during the aforementioned concert in Montréal: “Les moules aussi ont été inventé en Belgique!” (Mussels were also invented in Belgium!”)