From Dresses to Dollar Bills: Texture Connects Past and Present of Flemish Flax

From dresses to oil, dollar bills to cellos, the uses of flax are almost endless. The flax industry that developed on the banks of the river Leie brought unprecedented prosperity to southern West Flanders. At the Texture Museum in Kortrijk, you can take a contemporary look at exactly how this industry fared in the past and what innovative opportunities the plant offers today.

For centuries Flanders has been famous for its textiles. After wool and cloth in medieval Bruges and Ypres, from the fifteenth century onwards linen also played a major role. The basic linen that was woven on a massive scale in the area around the river Leie or Lys (its French name) was mainly intended for everyday use, while luxury products like lace and damask were very popular with both the nobility and the bourgeoisie.

In the nineteenth century the flax and linen industry brought unprecedented prosperity to the Leie region and, in particular, to the area round Kortrijk (French: Courtrai) in southern West Flanders, close to the French border. ‘Courtrai flax’ is still a quality product that is internationally known and in demand.

Texture

Texture© Jonas Vandecasteele

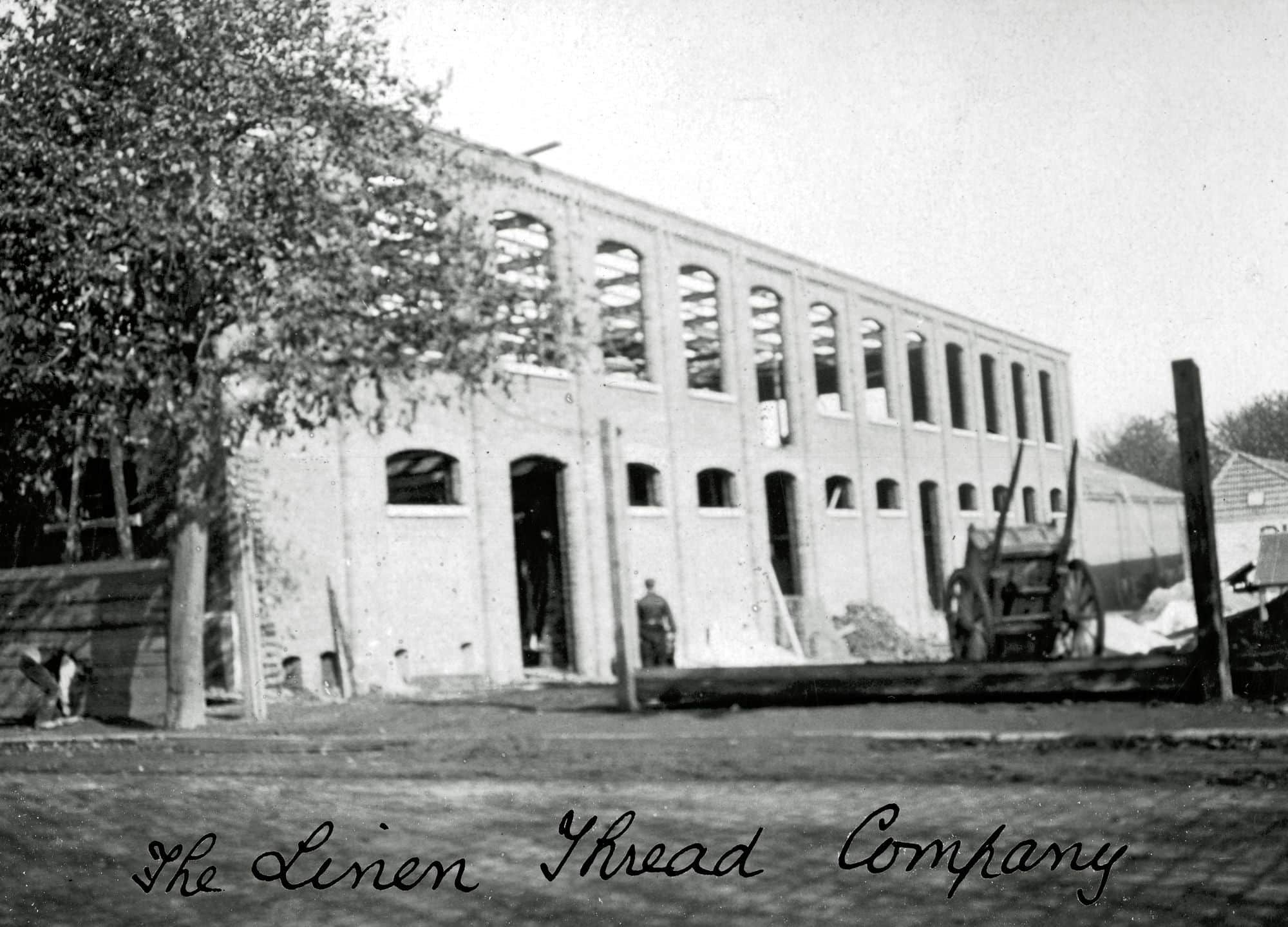

Texture Museum is located – where else? – on the banks of the Leie, in a building built just before the First World War by the English Linen Thread Company as a packing and shipping warehouse for scutched flax. Among flax workers the building had quite a reputation.

By working with Irish and Scots spinners and thanks to large group purchases, the Company was able to keep prices down. Locals sometimes mockingly called the building “The English Syndicate”. It symbolised the importance that the international linen industry attached to flax.

The English Linen Thread Company, now home to Texture

The English Linen Thread Company, now home to Texture© Linen Centre, Lisburn Museum Collection

Textile Garden

A visit to Texture begins outside, where a textile garden has been created on the square in front of the museum. Dye and textile plants like flax, hemp, madder, nettles, jute and woad have been sown in raised containers. Interested parties meet monthly in the Textile Garden to experiment with this local, sustainable production. Learning from each other, exchanging and passing on centuries-old textile techniques is the main objective. Inside, too, the museum’s mission is precisely to reconnect visitors with the origins of plant-based textiles and the region’s past.

Inside Texture

Inside Texture© Texture

In the Wonder Room, on the ground floor, we can immediately start experimenting. Over an area of a hundred square metres, we find every possible use for flax. And there are rather more than just making pure linen for a summer blouse. Flax fibre turns out to be an ingredient we are unaware of in many everyday products. You can see, feel and smell the wonderful versatility of these rather frail plants, with their deep blue flowers, in a box containing every different part of them.

Flax farmers at work in 1925

Flax farmers at work in 1925© Johan Desmet Foundation, Digital Collection Flax heritage Province of West Flanders

Flax in dollar bills

From the linseed chaff used in animal feed to the balls of scrap flax fibres used in acoustic insulation, no part of this ancient, cultivated crop goes to waste, every by-product is used. During rippling (removing the seeds), for example, oil is extracted from the flax stalks. Linoleum flooring is derived from flax fibre, as well, and even cigarette papers and dollar bills contain elements of flax. Since the early 1960’s the world’s oldest flax company, near Kortrijk, has supplied the United States with the flax fibre that is used in the famous one-dollar bills. It makes them sturdy and gives them a silky touch. The US notes crackle less, too, than euro notes, which are made entirely of cotton.

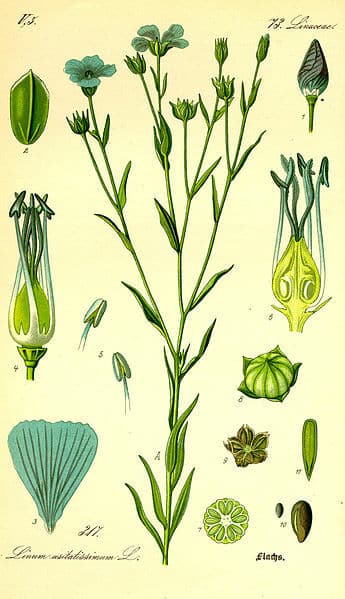

Linum usitatissimum, the Latin name for the flax plant says it all: 'very useful'.

Linum usitatissimum, the Latin name for the flax plant says it all: 'very useful'.© Wikimedia Commons

Linum usitatissimum, the Latin name for the flax plant says it all: ‘very useful’. The interior of the museum itself is made of flax products, from insulation to flooring. Flax as a basis for building materials is gradually being reappraised for its numerous applications and great durability. A nice anecdote is that flax even played a role in the production of the Mystic Lamb. Jan Van Eyck painted on linen canvas and used linseed oil as a binder for the pigments he used to make his beautifully durable paint.

The uses and possibilities flax offers, as the strongest and lightest natural fibre in composites that can serve all kinds of purposes, are impressive. There is even a full-blown cello made of flax in the museum. A love for this little plant that used to fill the swaying light blue fields of long-ago summers has been completely rekindled. But, if it has such a wealth of potential, why is there no longer large-scale cultivation of flax?

Decentralised industry

The Leie or Lys Room on the first floor provides clear information about the turbulent history of the flax industry, which flows like a river, with periods of glory and moments of deep crisis.

During the fifteenth century Kortrijk specialised in weaving damasks. Woven with white flax-fibre yarn on a jacquard loom, damasks are fabrics on which, when they are looked at from a certain angle, a motif becomes visible in the background. Around this time, the lace industry also became increasingly popular.

The local textile industry boomed in the sixteenth century, with a huge rise in linen production after Europeans discovered America

The local textile industry really boomed in the sixteenth century, with a huge rise in linen production after Europeans discovered America. Flemish linen found a big market in Spain, which boosted its trade with the ‘New World’ with it. This illustrates nicely that local industry cannot be disassociated from larger developments on a geopolitical and economic level.

By the eighteenth century, the flax industry was still the only industry in Flanders, and it was almost entirely rural. Remarkably, too, it was decentralised, there was no mention of large factories in the city. Small retteries and scutching factories sprang up around the river Leie. Over the years, production shifted downstream. The difference in situation and social status of the various occupations in the flax industry was huge and the hierarchy rigid.

Golden River

To make them supple, flax stalks were retted (i.e. soaked) in pools and marshes. In the nineteenth century, when flax was retted in massive quantities in the flowing water of the Leie, the legend developed that the Leie water had special chemical properties that promoted retting, giving the river its nickname, the ‘Golden River’. However, the cause and effect were probably reversed in popular parlance, retting did after all turn the Leie water a yellowish colour. In a figurative sense though, the Leie did bring ‘gold’ and prosperity to the region.

In the nineteenth century, flax was retted en masse in the flowing waters of the Leie river. The retting made the flax stalks supple.

In the nineteenth century, flax was retted en masse in the flowing waters of the Leie river. The retting made the flax stalks supple.© City of Kortrijk

With the emergence of new techniques like hot retting, flax processing could now take place further from the Leie. The bends of the river were straightened to allow increased shipping traffic, old Leie arms were cut off from the current and new industry appeared along new canals. This is the historical explanation for the emergence of ribbon development and the gradual urbanisation of flax villages.

For centuries, thousands of people found a livelihood in this branch of the textile industry, as all the processing was done manually. However, mechanisation, competition from abroad, the rise of the cotton industry and synthetic textiles from low-wage countries, Eastern Europe and the Far East dealt the Flemish linen industry a severe blow. With its disappearance, a whole vocabulary was gradually lost, and even a way of life.

For centuries, thousands of people found a livelihood in the flax industry, as all the processing was done manually.

For centuries, thousands of people found a livelihood in the flax industry, as all the processing was done manually.© De Bethune Foundation Marke

After all, flax was extremely important for this whole region. It left its mark not only economically, but even on social life. That story is extensively illustrated in the Leie/Lys Room. There we learn that the Kortrijk flax exchange opened on Mondays and lots of flax was traded. Payments were made at drinking establishments and accompanied by lots of beer.

Flax processing required heavy manual labor.

Flax processing required heavy manual labor.© Johan Desmet Foundation, Digital Collection Flax heritage Province of West Flanders

Videos with historical recordings and interviews with elderly former flax workers offer a wealth of information, in juicy West Flemish dialect with their very own jargon. Words like zwingelen (scutch), roten (ret), slijten (hackle), repelen (ripple), haspelen (spool) and klossen (reel) have almost disappeared from our vocabulary. Other words have taken root in fixed expressions, such as ‘over de hekel halen’ (to criticize someone or something mercilessly). The hackle (hekel) was a plank with strong thick teeth used for combing flax fibres in the same direction to prepare them for spinning. The inclusion of this word in the general Dutch vocabulary shows how important the industry was for a large part of the population in the Leie region.

Flax Museum 2.0

Texture began as the Flax Museum, in 1982. With the crisis in the flax industry in the 1960s, fears grew that the most important economic activity in the south of West Flanders would disappear. The story of the region and its heritage were also in danger of being lost. An instructive collection of flax implements gathered by the founder Bert Dewilde grew into a collection that is unique in Europe. In 1998, these implements, including a hackling machine and a scutching turbine that were included by Flanders in a list of top pieces, were supplemented by a collection of lace and linen.

Superb linen and lace, made in Kortrijk

Superb linen and lace, made in Kortrijk© City of Kortrijk

Joseph de Bethune, scion of a family of linen merchants built up an impressive collection of textiles. Among other things, the collection includes internationally renowned Kortrijk damasks. Superb garments and other pieces from the collection can be admired on the top floor. It would be hard to get bored of the sophistication and complexity of some of the motifs. Pure mastery.

However, Texture is not stuck in the past. Those who are interested can follow workshops to master the old flax processing techniques themselves, in combination with contemporary technology. Artists are also welcome for research or residencies. Photographer and canoeist Danny Veys, for example, was conducting artistic research that meanders through the history of the Leie region. He built a canoe in flax composite and explored the river and the surrounding landscape while paddling on the water and with his camera in his hand. Danny collected and processed new images and stories because the story of flax has not yet been told in this region.

Danny Veys and Francis Soenen paddled down the Leie, from source to mouth, in a canoe made of flax composite.

Danny Veys and Francis Soenen paddled down the Leie, from source to mouth, in a canoe made of flax composite.© Jan Vanhulle

Infectious

A visit to Texture is well worth the effort. The appreciation of artisanal finesse, the craftsmanship and love of the raw material and beautiful fabrics is infectious. It makes you pause to wonder why the versatility and sustainability of a plant like flax has lost out to synthetic fabrics of inferior quality in the fast fashion industry. And whether the revaluation of quality and sustainability might cause a resurgence. There is certainly nostalgia for craftmanship and some regional pride in the museum, but Texture also provides context and broadens the focus. And look, if the sun is playing softly on the water as you leave the museum, the Leie actually sparkles golden in the bend.