That’s Why I Happily Write With My Chatbot

Dutch linguist Marc van Oostendorp is still astonished by what ChatGPT and its counterparts can do. Nonetheless, he has seamlessly integrated this artificial intelligence into his work. In this piece, he argues that collaborating with a chatbot positively impacts both the writer and the reader.

Now I understand the emotions a biologist might feel upon discovering life on Mars – perhaps single-celled life, concealed beneath a layer of dust covering the planet, but undeniably life, slightly different from what we know on Earth, yet exhibiting the same resilience. This life offers valuable lessons and, furthermore, complements our understanding of Earth. Since 30 November 2022, linguists have been able to experience the mixture of amazement, shock, and excitement that such a revelation would evoke in a biologist. It was on that day that ChatGPT became accessible to the public.

Until that moment, in our known universe, there was only one being capable of endlessly creating new sentences: homo sapiens. Yes, bees could communicate the location of honey to each other through dance, and computers could highlight potential language errors with red squiggles. However, writing a text about honey was an exclusive ability of humans. And just like that, the chatbot emerged.

From that moment onward, we embarked on a quest to understand the importance of this revelation and beyond. Exploring how we can understand our language abilities compared to this artificially crafted alien, and contemplating how artificial intelligence might assist us in becoming better readers and writers.

Underestimation

ChatGPT and rival chatbots from companies like Google and Meta are far from perfect. As of now, no reader has replaced the collected works of Shakespeare and Dostoevsky with a computer-generated story to read at night. Most users are aware that relying solely on a machine for medical or legal assistance should be avoided without human verification of the advice. Likewise, when dealing with a lengthy and intricate contract that could potentially result in significant costs, it’s advisable to go through it yourself at least once.

Nevertheless, I have been observing the developments in how computers handle language since approximately 1987. If you had asked me on 29 November 2022, whether computers could write a poem on any subject, pass a Dutch language exam, or create a bullet-point summary of an article from Le Monde, you would have encountered my anger and scepticism – how dare you give me such nonsense? Now, all these capabilities are at the fingertips of every internet user.

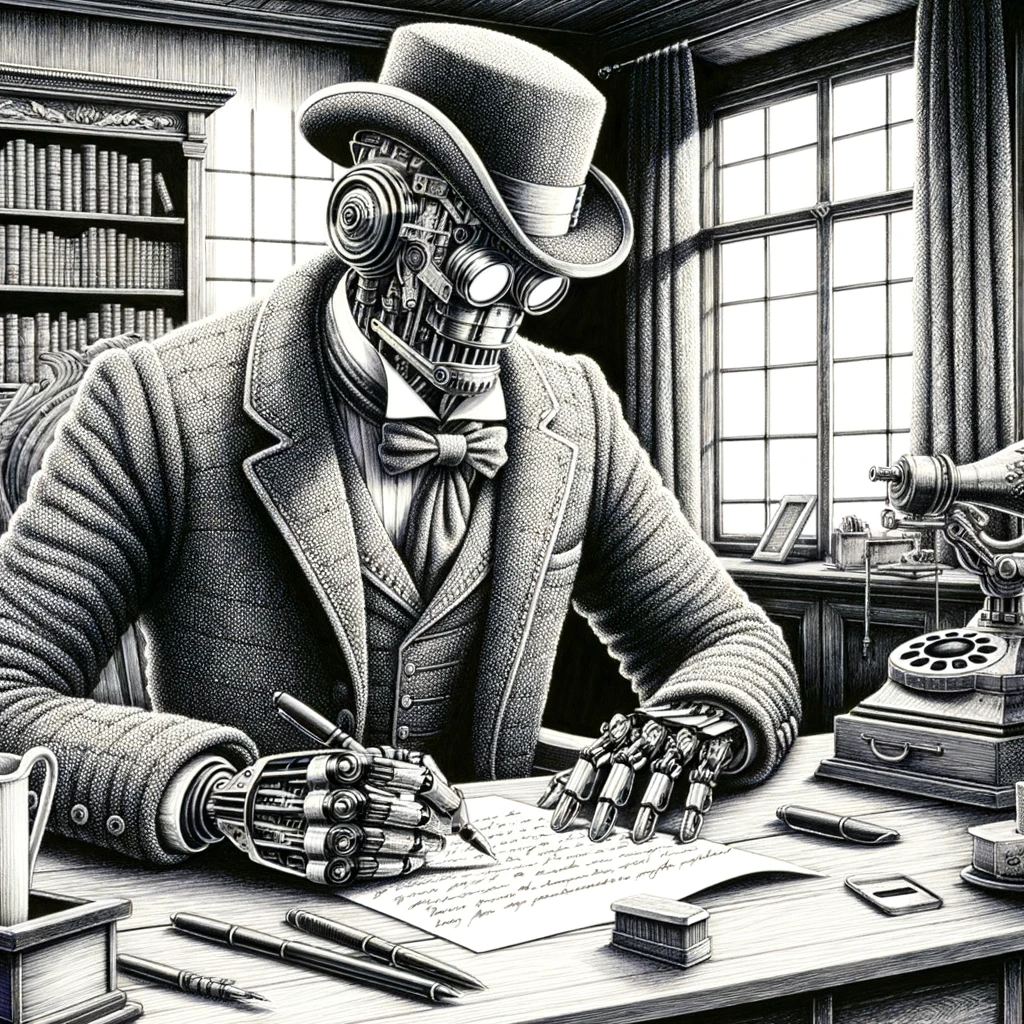

Artificial intelligence created this illustration based on the task of coming up with an image to accompany the article on writing with a chatbot.

Artificial intelligence created this illustration based on the task of coming up with an image to accompany the article on writing with a chatbot.© DALL-E

I’m still amazed – and I don’t think anyone in the world has fully wrapped their heads around it, not even the engineers behind these chatbots. Back on 30 November 2022, we crossed another boundary: humans have created something they can no longer predict. Most machines are entirely predictable: press the button on this coffee maker ten times, and you will get ten cups of identical cappuccino. But pose the same question to a chatbot ten times, and you will get ten different answers.

We are currently inclined to underestimate these machines. In 2023, when researchers asked participants whether a given news article was written by a human or a computer, they guessed correctly in only fifty-two percent of cases – just slightly above the percentage of a blind guess. Interestingly, participants tended to believe a text was human-authored when it contained few grammatical errors and longer words. Ironically, humans typically make slightly more grammatical errors and use shorter words than chatbots.

Truth

How chatbots work has been explained before, and at its core, it’s quite simple: they operate by predicting the most likely next word based on the context provided in the preceding text. After ‘I see an orange…,’ the word fruit is more likely than the word idea because the former occurs more frequently in texts with a similar sentence than the latter. However, the computer autonomously assesses which aspects of the context to prioritize for this calculation, involving so many factors (millions) that it becomes overwhelming. This results in a system emerging from that simple principle that we no longer understand.

After that, the chatbots underwent further training by individuals who continually posed questions, engaged in extensive conversations, and provided continuous feedback on their responses. Subsequent interactions were partly shaped by this ongoing exchange. This is how language evolves for chatbots: they produce texts designed to be as predictable as possible, selecting the version that receives the most positive feedback. In other words, they are primarily adept at writing texts following a fixed pattern – recipes, news articles – or texts that are extremely focused on pleasing, such as social media posts.

Chatbots are primarily adept at writing texts following a fixed pattern or that are extremely focused on pleasing

An important distinction from humans lies in the fact that computers do not experience the world: they haven’t acquired their native language from a mother but from billions of texts. While they are familiar with the word rose, they lack knowledge of how a rose smells or how the petals feel. They struggle to differentiate between fantasy and reality. Numerous examples illustrate chatbots generating entirely fictional responses to questions. The underlying reason is that the pursuit of truth is not treated as a distinct criterion in the training: rather, truth is determined by what is frequently said or what people enjoy hearing.

Efficient assistant

Both humans and chatbots have their strengths. Humans experience the world and provide unique perspectives, while chatbots excel in articulating ideas in a way that resonates with a broad audience. This collaboration with a chatbot positively impacts both the writer and the reader. Without a doubt, I have integrated this collaboration into my work as a professor of Dutch and Academic Communication.

For me, chatbots have become indispensable, serving as automated editors. I subject everything I write – whether it’s a scientific article or a business email – to scrutiny by a systematic editor. I instruct it to be a ‘very strict editor,’ focusing on spelling, typing, and language errors, the structure of the argumentation, and providing substantive tips.

An important distinction from humans lies in the fact that computers do not experience the world: they haven’t acquired their native language from a mother but from billions of texts

A psychological quirk is that the chatbot always starts by showering me with extensive compliments on my vast expertise and brilliant sense of style. I do have an audience, at least, although experience tells us that I receive this feedback even when presenting total nonsense (the chatbot is a pleaser). However, afterward, I usually receive sensible remarks. I handle them the way I would with feedback from a human editor: using it to correct mistakes, but more importantly, to look at my own writing from a different perspective. Is the connection between two paragraphs truly as illogical as the chatbot suggests? Is the proposed rephrasing genuinely an improvement? Or, upon closer inspection, would I formulate that sentence in a completely different way?

I also let my chatbot write texts, but only in genres where it does better than I do. For example, in my role as an editor for a scientific journal, I handle a lot of correspondence. The submitted articles are presented to three peers who write an anonymous assessment for the author. Based on these evaluations, I must decide whether to proceed with publication and determine if any further edits are needed. Crafting an email summarizing the assessors’ arguments is a key step in this process. Summarizing and maintaining a positive tone are tasks chatbots handle better and faster than I do. Afterwards, I make sure the sent email only includes the things I genuinely find important and want to emphasize. I also fine-tune the wording to ensure the text reflects my desired tone. The chatbot alone wouldn’t be able to do it; for me, it would require much more work without such an efficient assistant.

Illustration created by artificial intelligence

Illustration created by artificial intelligence© DALL-E

Another task for which I frequently use chatbots is my work as a teacher. I find few things as challenging as creating exams: devising questions that are neither too difficult nor too easy, questions that provide insight into whether students have mastered all aspects of the material, and that are also not too superficial. Crafting questions that result in reasonably competent students earning fair grades, while also maintaining a somewhat balanced distribution of low and high grades. Quite a challenging task.

I let my chatbot write texts, but only in genres where it does better than I do

Even in this scenario, chatbots don’t necessarily need to do better than me; rather, together, we can perform the task much more effectively than I can on my own. I ask the system for question suggestions, and I also present those questions to see the responses it generates. I know teachers who have submitted all national French exams from the Netherlands for the past ten years to chatbots to determine if some exams are more challenging than others. You could attempt to do this as a human, but it would take you weeks.

Chess computers

The mentioned techniques may not have long-term viability. Chatbots have undergone impressive improvements since 30 November 2022, and we do not know where these advancements will plateau. I can anticipate notable progress in the years to come. However, it also wouldn’t surprise me if, in the next few decades, major improvements are not expected. The ambiguity of how they precisely function leaves us uncertain about whether they can genuinely improve further, or if they might already be suggesting improvements in their own design.

Illustration created by artificial intelligence

Illustration created by artificial intelligence© DALL-E

Should it become much better than it currently is, imagination runs wild. Systems could potentially write autonomously, allowing journalists, researchers, and frequent writers to develop personalized systems that write texts for them.

And it wouldn’t end there. Why should readers settle for a predetermined style? They might prefer to choose themselves how they consume content, perhaps enjoying my insights in the styles of Tom Lanoye or Manon Uphoff, just as they might select a specific style for their weather updates or a letter from the tax office. Why must the writer dictate the style in which ideas are presented to the readers?

Illustration created by artificial intelligence

Illustration created by artificial intelligence© DALL-E

A potential division of labour could exist between idea suppliers and style providers. The former could present their ideas through bullet points, while the latter might offer their style for subscription. Moreover, some styles are now copyright-free. Imagine reading all the current world news as if it were written by Multatuli!

But even when that happens, people will discover that an important reason to read is the desire to connect with other human beings, with creators of flesh and blood, with desires and childhood memories, an inner life, and a fear of death – even if those people have fewer brilliant ideas than computers and express them in a less brilliant style. So, there will always be human writers.

Let us collectively work on establishing open and public artificial intelligence models and actively enhance their energy efficiency

I believe there is something to learn from the history of chess computers. When the first artificial intelligence emerged, capable of effortlessly defeating any human chess player, predictions were made that it would signal the end of the game of chess. It’s not fun to play if a pile of silicon can always beat you, right? Indeed, I believe few people play for fun against the very best chess computers. However, this hasn’t led to the disappearance of chess. On the contrary, chess is thriving more than ever, especially online – predominantly played among imperfect humans. The enjoyment lies in winning against a fellow human rather than a computer, even if the latter is specifically set to your level.

Enrichment

However, there are indeed issues with chatbots that must not be overlooked. They consume substantial energy, are trained on materials created by uncompensated individuals, and most importantly, are exclusively controlled by large corporations, leaving us uncertain about the entities behind these devices when we use them.

These are significant problems requiring solutions. This seems feasible if we collectively work on establishing open and public artificial intelligence models and actively enhance their energy efficiency.

If all of that unfolds, we can only benefit from the introduction of this new into our lives on 30 November 2022 – one that reads and writes differently than us, thereby enhancing our own reading and writing.