The American Adventure of 17th-Century Stained Glass From Flanders

When the religious order at the Park Abbey near Leuven fell on hard times in the 1820s, it sold off a remarkable set of 17th-century stained-glass windows. Split up, passed on, sold and resold, many of the windows ended up in the USA. Now 21 of the 41 windows have been restored to the abbey’s cloister, which reopened this spring.

The Park Abbey was established in 1129 on hunting grounds donated by the Duke of Brabant to the Premonstratensian order of canons, also known as the Norbertines, after their founder St Norbert of Xanten. Throughout the Middle Ages the abbey expanded, adding buildings and developing its extensive grounds. Then, during a period of renovation in the 17th century, the abbot commissioned a set of stained-glass windows to enclose the abbey’s cloister.

The Park Abbey near Leuven

The Park Abbey near Leuven© Park Abbey, Leuven / Marco Mertens

The windows were made between 1635 and 1644 by Jan de Caumont, a master of glass painting who had a workshop in Leuven. Each window originally consisted of nine elements. In the middle was a narrative scene from the life of St Norbert, with a related Latin verse below, and an abbot’s coat of arms above. To either side were full-length figures of notable Norbertines, with text panels identifying them below, and decorative elements above, such as garlands and cornucopias.

Unlike church windows, which are generally set high up and designed to be seen from a distance, the Park Abbey windows were at eye level. With their striking colours and finely painted detail, they were intended to be seen by the canons as they went about their duties, a daily reminder of their history and values.

The Parc Abbey cloister with the stained glass in place.

The Parc Abbey cloister with the stained glass in place.© Park Abbey, Leuven / Cedric Verhelst

And so they were for a century and a half, until the abbey was closed by the French revolutionary government in 1797. Although the Norbertines soon recovered the buildings, religious life could not resume at the Park Abbey until 1836. Meanwhile, many of its remaining artworks were sold to raise funds for the struggling order, including the stained glass from the cloister.

The windows were bought in 1828 by the wealthy Brussels ship-owner Jean-Baptiste Dansaert, who obligingly paid of replacement glass around the cloister as well. Little is known about how he used the windows, but the set appears to have been kept together, at least until the death of Dansaert’s widow in 1853, when they were divided equally between their three daughters.

One of Jan de Caumont’s windows is inspected at the Park Abbey.

One of Jan de Caumont’s windows is inspected at the Park Abbey.© Park Abbey, Leuven

Tracing their subsequent history is complicated by the fact that we do not know precisely how the windows were shared out. It also appears that there was some mixing and matching of their constituent parts after the split, with one surviving window made up of elements known to have passed through separate lines of inheritance.

What we do know of their fate is largely down to the research of Ellen M Shortell, emeritus professor of art history at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She has worked on the Park Abbey windows for more than 30 years, and is currently preparing a book on the subject.

In the late 1880s a Brussels art dealer sold windows individually or in small batches to private collectors in England and France

Archive sources allowed her to trace one group of windows as it passed from the Dansaert family to Belgian architect Charles Licot, and then on to a Brussels art dealer called Moens. In the late 1880s Moens sold the windows individually or in small batches to private collectors in England and France. One set went to the Viscount and Viscountess of Janzé, who used the glass to decorate the stairway and dining room of their Paris house.

This is where the American connection begins. New York architect Stanford White was frequently in Europe during the 1890s, looking for art and antiquities to furnish the houses of rich clients. He was familiar with the windows in the Janzé house and eventually negotiated to buy them for a mansion he was renovating for the financier and railroad magnate William C Whitney.

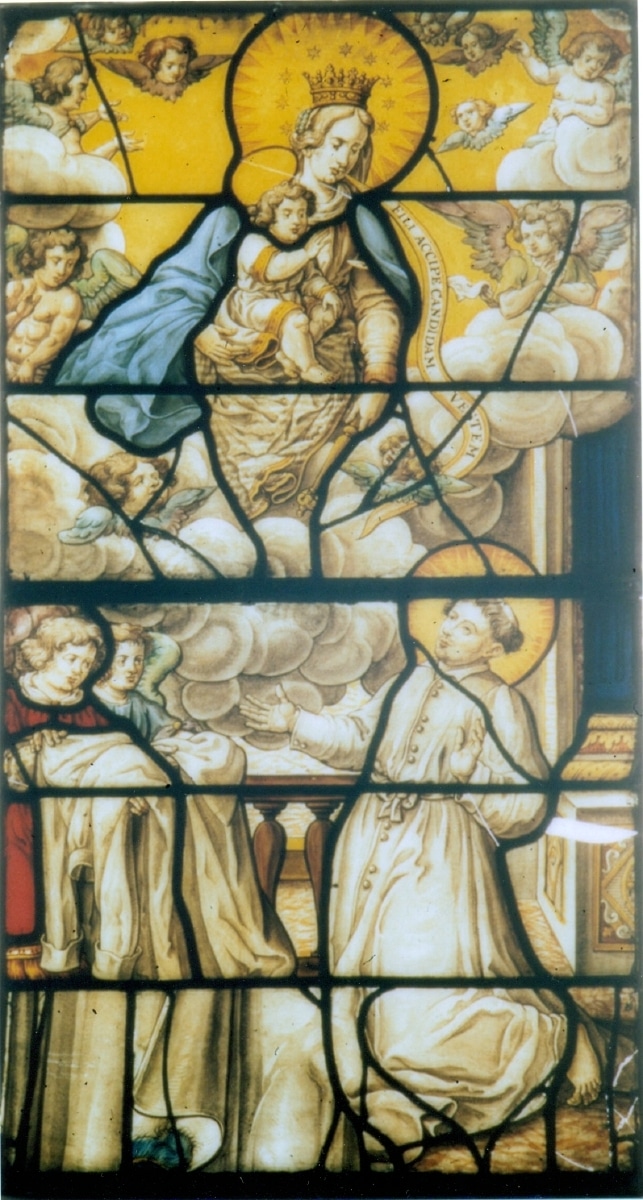

In a vision, Norbert receives the white habit from the hands of Our Lady. Previously in William Whitney’s mansion, and Yale University Art Gallery

In a vision, Norbert receives the white habit from the hands of Our Lady. Previously in William Whitney’s mansion, and Yale University Art Gallery© Park Abbey, Leuven

But White also appears to have tracked down and bought several other Park Abbey windows, some of which were in his studio when he died. It is hard to be sure where they came from, since his correspondence obscures his sources, a double mystification calculated to woo clients and distract any competition. He also had to be discrete in the face of local resentment at the way Americans appeared to be bulk-buying European heritage and shipping it across the Atlantic.

Whitney’s mansion was on Fifth Avenue in New York, in a stretch overlooking Central Park then known as Millionaire’s Row. White’s thorough renovation included using glass from the Park Abbey windows as a backdrop for a monumental staircase, and to fill bay windows in a corridor leading to a ballroom. The goal was to add colour to the social events held in this part of the house, and fitting the glass took little account of the original relationship between the panels.

The staircase windows went to Yale University Art Gallery, which kept them in storage for 70 years before selling them to the Flemish Community in 2013

After Whitney’s death in 1904 the stained glass remained where it was until the mansion was demolished in 1942. The staircase windows then went to Yale University Art Gallery, which kept them in storage for 70 years before selling them to the Flemish Community in 2013. Consisting of roughly eight original windows, the glass returned to the Park Abbey in 2016.

The bay windows were sold to Dr Preston Pope Satterwhite, who installed them in his Fifth Avenue apartment. On his death they were left to the JB Speed Museum in Kentucky, where they currently feature in the museum’s tapestry room.

A false penitent and other conspirators prepare to kill Norbert. Window formerly in William A Clark’s mansion, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art.

A false penitent and other conspirators prepare to kill Norbert. Window formerly in William A Clark’s mansion, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art.© Park Abbey, Leuven

Shortly after work on Whitney’s house was completed, a further set of Park Abbey stained glass arrived on Fifth Avenue, to grace a vast mansion being built for ‘Copper King’ and US senator William Andrews Clark. The six windows were installed in the third-floor library, stacked two-by-two but otherwise with most of their elements intact. In contrast to the Whitney house, where the glass was used to create a mood, here they were treated as part of Clark’s extensive art collection.

Precisely where Clark’s windows came from is again unclear. Professor Shortell thinks Stanford White may have had a hand in it, either telling Clark about them or supplying some himself. On the other hand, the francophile Clark was a frequent visitor to Paris and may have found the windows independently.

The William A Clark's windows returned to the Park Abbey in 2014

After Clark’s death in 1925, more than 200 works of art from his collection were bequeathed to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington DC, along with the windows. Here they stayed until 2014, when financial difficulties forced the gallery to close. Most of its collection went to the National Gallery of Art or other local institutions, but an exception was made for the Park Abbey windows, which were returned home.

Other Park Abbey windows that may have found their way to the USA during the Gilded Age are considered lost, although surprises are always possible. In 1995 two narrative scenes surfaced at a Sotheby’s auction in New York, and were snapped up by the Friends of the Abbey. These passed through Stanford White’s studio, but little more is known about their history.

Norbert meets Emperor Lothair II, in one of the windows donated to the Abbey in 1971 after failing to sell in the USA.

Norbert meets Emperor Lothair II, in one of the windows donated to the Abbey in 1971 after failing to sell in the USA.© Park Abbey, Leuven

Of the Park Abbey windows that remained in Europe, some stayed with Dansaert families, split and split again by inheritance. Three of these windows were donated to the Park Abbey in 1971, after they failed to sell in the USA. Others were sold to private collectors in Belgium and England, with a few resurfacing only after decades in obscurity.

Norbert, apostle of the Sacrament, a partial scene donated to the Abbey by JC Nieuwenhuys in 1937.

Norbert, apostle of the Sacrament, a partial scene donated to the Abbey by JC Nieuwenhuys in 1937.© Park Abbey, Leuven

One partial narrative scene and a coat of arms was given to the abbey in 1937 by a certain JC Nieuwenhuys, of whom little more is known. By happy chance the Latin verse associated with this scene was among the glass returned to the abbey from Yale. Another stray verse panel turned up in 2005, and was bought for the abbey.

Two other windows ended up in a castle at Heist-op-den-Berg, in Antwerp province. These were sold to the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels in 1956, where they remain and have recently been returned to public view. One window can be found in an apartment building on Brussels’ up-market Avenue Louise, while another is in the private chapel of the Château de Pallandt in Bousval, Walloon Brabant.

Norbert accompanies Pope Innocent II into Rome, in the collection of the Royal Art & History Museum, Brussels

Norbert accompanies Pope Innocent II into Rome, in the collection of the Royal Art & History Museum, Brussels© Royal Art & History Museum, Brussels

There is little chance of these windows returning to the abbey in the near future, and all the available leads for the remaining ‘lost’ windows have been investigated. But the abbey hopes that the publicity around the re-opening this spring, together with an exhibition on the Norbertine canons, might yet bring others to light.